I recently spent a day at the Ninth Fort in Kaunas, Lithuania, where my mother’s favorite cousin, Jutte, was shot at age 16, along with her mother and  996 other Viennese Jews, on November 29, 1941. I wasn’t sure why I wanted to go there, but now I know – it was a powerful experience to be where I know a particular family member was killed, on a particular day.

996 other Viennese Jews, on November 29, 1941. I wasn’t sure why I wanted to go there, but now I know – it was a powerful experience to be where I know a particular family member was killed, on a particular day.

And it made me angry, because so much of the Ninth Fort museum and the whole project of memorializing the history of genocide and terror in Lithuania is dedicated to preventing the murders of hundreds of thousands of Jews during the Nazi era from overshadowing the murders and terror visited on non-Jewish Lithuanians during the Soviet eras.

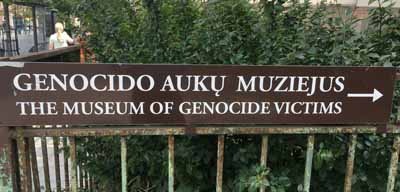

Two days earlier I visited the Museum of Genocide Victims in Vilnius,* which dedicates dozens of rooms to the oppression of Lithuanian Gentiles under the USSR, and only one to the genocide of the Lithuanian Jews. In fairness, the museum is in a building that served for decades as a KGB prison, where thousands of Lithuanians were held, tortured, and in some cases killed, and that history deserves to be commemorated. But…

…the use of the word “genocide,” and specifically the use of Jewish deaths in service of the narrative of non-Jewish suffering is striking. For example, there is a large panel showing the numbers of Lithuanians killed by the Soviets and Nazis: First the roughly 75,000 deaths during fifty years of Soviet occupation, from 1940 to 1990 — 20-25,000 “prisoners who died”; 28,000 “died in deportation”; and 21,500 “Partisans and their supporters killed.” Then the number killed during the four years of German occupation, between 1941-44: “240,000 killed (including about 200,000 Jews).” That is how they phrase it, with the parenthesis.

…the use of the word “genocide,” and specifically the use of Jewish deaths in service of the narrative of non-Jewish suffering is striking. For example, there is a large panel showing the numbers of Lithuanians killed by the Soviets and Nazis: First the roughly 75,000 deaths during fifty years of Soviet occupation, from 1940 to 1990 — 20-25,000 “prisoners who died”; 28,000 “died in deportation”; and 21,500 “Partisans and their supporters killed.” Then the number killed during the four years of German occupation, between 1941-44: “240,000 killed (including about 200,000 Jews).” That is how they phrase it, with the parenthesis.

Of course, it’s fair to argue that numbers are not the whole story – except, in the case of Jews, in this museum, numbers ARE the whole story. Not one Jewish Lithuanian is mentioned by name in the entire museum.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the power of naming since reading Ari Shavit’s book, My Promised Land. For those who don’t know it, it is a liberal Zionist’s exploration of Israeli history, which purports to fairly acknowledge the suffering of the Palestinians. But Shavit’s careful even-handedness is consistently numeric and falls apart at the level of naming and specificity. In a long chapter on the terrorist bombings and killings of the 1930s, he scrupulously notes that there were more Palestinians killed by Jewish terrorists than Jews killed by Palestinians – but the Jewish victims are consistently named, along with their ages and details about who they were and what they were doing when they were killed (walking home from a movie, tending an orchard, studying), while the Palestinian victims are just numbers, all but a couple unnamed, no ages provided. I’m guessing Shavit did this unconsciously, but that’s not a defense: on the contrary, it underscores the degree to which Jews, for him, are human beings, while Palestinians are not.

That division is maintained throughout the book. For example, a chapter on the ethnic cleansing of Lydda describes how Jewish government forces murdered men, women, and children, drove thousands of people from their hom es and sent them on a forced march in which the weak fell and died, destroying towns and villages in a region where Arabs had treated arriving Jews as friends and neighbors. Shavit frames this as a devastating indictment of Israeli policy — but in 32 pages mentions the name of only one Arab. He begins by telling how named Jews settled in the area and befriended unnamed Arabs; tells of meetings between named Jewish leaders and unnamed Arab leaders; and quotes named Jewish perpetrators about their attacks on unnamed Arab victims. Even when an Arab is finally named, as a victim with his family of the death march, he is never quoted directly—unlike numerous Jewish witnesses—and Shavit’s sympathetic description of the abuses inflicted on his father, mother, cousin, grandmother, and brothers does not include their names. Jews are condemned for committing atrocities, but they are individuals, with names and voices; the Arabs are nameless and voiceless.

es and sent them on a forced march in which the weak fell and died, destroying towns and villages in a region where Arabs had treated arriving Jews as friends and neighbors. Shavit frames this as a devastating indictment of Israeli policy — but in 32 pages mentions the name of only one Arab. He begins by telling how named Jews settled in the area and befriended unnamed Arabs; tells of meetings between named Jewish leaders and unnamed Arab leaders; and quotes named Jewish perpetrators about their attacks on unnamed Arab victims. Even when an Arab is finally named, as a victim with his family of the death march, he is never quoted directly—unlike numerous Jewish witnesses—and Shavit’s sympathetic description of the abuses inflicted on his father, mother, cousin, grandmother, and brothers does not include their names. Jews are condemned for committing atrocities, but they are individuals, with names and voices; the Arabs are nameless and voiceless.

After reading that book I started paying closer attention to when historical narratives include names, ages, photographs, and details of individuals and when they only give numbers. It is an interesting exercise, and often very revealing – in the US, it has become common for historical narratives to refer to the genocide of Native Americans, but how many mention any of the victims by name?

I came to Lithuania following Jutta’s story, bringing her picture and the story of how she got stuck in Vienna, the number of the transport that brought her to Kaunas, and the date when the 998 Viennese Jews on that train were chased up the hill at the Ninth Fort, pushed into mass graves, and shot – or in some cases shot, then pushed into mass graves. I wondered if the museum might be interested in having a copy of the photograph of Jutte and her mother, Gustl.

I came to Lithuania following Jutta’s story, bringing her picture and the story of how she got stuck in Vienna, the number of the transport that brought her to Kaunas, and the date when the 998 Viennese Jews on that train were chased up the hill at the Ninth Fort, pushed into mass graves, and shot – or in some cases shot, then pushed into mass graves. I wondered if the museum might be interested in having a copy of the photograph of Jutte and her mother, Gustl.

Then I went through the museum at the entrance to the fort. The first section is a dramatic, full-room stained-glass installation titled “Undefeated Lithuania.” Then we get the history of the first Soviet occupation, 1940-41, with photos and biographies of Lithuanians who were exiled or killed, and details about what happened to each of them. There is a panel on the “Priests’ Massacre in Budavone Forest,” showing the three priests who were killed. There is a panel on the “Massacre of Panevezys Physicians,” with names and photos of the four physicians who were tortured and killed. Then there are multiple panels on the deportations of Lithuanians during the second Soviet occupation, after 1944, with names, photos, and objects belonging to the victims, like the seven-string guitar V. Lapiusko brought with him to Siberia.

There is a display in this room about the Nazi period, with photographs of the Kaunas ghetto, yellow stars, and Jewish corpses.  It gives the numbers of Lithuanian Jews killed, and displays personal items – eye glasses, shaving brushes, a pair of child’s shoes – found in the mass graves. It is a touching display. Not one Jew is named.

It gives the numbers of Lithuanian Jews killed, and displays personal items – eye glasses, shaving brushes, a pair of child’s shoes – found in the mass graves. It is a touching display. Not one Jew is named.

There are pictures from Nazi extermination camps outside Lithuania: Ravensbruck, Bergen-Belsen, and Auschwitz-Birkenau. The photos are horrifying, but identified only by camp, except for a display titled “Lithuanian intellectuals at Stutthof concentration camp,” which includes names, photos, and biographies of those intellectuals and mentions that 85,000 people were killed there, including 1,100 Lithuanians.

The Nazi display also includes one document that suggests why a patriotic Lithuanian museum might want to shift the discussion from local details to the broader German genocide. It is a typed report from a German officer on July 11, 1941, explaining that a ghetto has been established for the remaining Jews in Kovno (Kaunas). The accompanying label translates a key paragraph: “In Kovno a total of 7,800 have now been killed — a portion through the pogrom, a portion shot by Lithuanian commandos. All corpses have been disposed of. Continued mass shootings are no longer possible. Instead I explained to a committee of Jews that up to now, we have not had a reason to intervene in the internal conflicts between the Lithuanians and the Jews…” Unlike every other display in the room, this document is labeled and translated only into English – not into Lithuanian.

There is a second museum in the fort itself, for those who wish to delve deeper. It was largely funded from abroad, and includes rooms with photographs of individual Jews, their names, their stories. There is a powerful display sponsored by “Les Familles et Amis des Déportés du Convoi 73, Paris (France),” about a transport of 878 French Jews killed here in 1944, including walls of photographs identified by name. There is a room about the Kaunas ghetto, with family pictures, names, and stories from survivors. There is a room about the escape of 64 prisoners who were brought in 1943 to burn the thousands of corpses, naming them and noting that 60 were Jews, along with three Russians and a Pole. There is a room with stories of survivors, saying what happened to them in later years. There is a room about the Japanese consul who in defiance of his government provided six thousand Jews with exit visas. There is a room about “Lithuanians, the Saviours of the Jews,” with stories of Lithuanian Gentiles who hid or helped their Jewish neighbors. And there is a room about Hitler and the genocide of European Jews, with names of 1,344 Jews from various parts of Europe who were killed here, each with their age and home town. Jutta and Gustl were not included – I looked for them, and the omission bothered me. But to continue…

There is a second museum in the fort itself, for those who wish to delve deeper. It was largely funded from abroad, and includes rooms with photographs of individual Jews, their names, their stories. There is a powerful display sponsored by “Les Familles et Amis des Déportés du Convoi 73, Paris (France),” about a transport of 878 French Jews killed here in 1944, including walls of photographs identified by name. There is a room about the Kaunas ghetto, with family pictures, names, and stories from survivors. There is a room about the escape of 64 prisoners who were brought in 1943 to burn the thousands of corpses, naming them and noting that 60 were Jews, along with three Russians and a Pole. There is a room with stories of survivors, saying what happened to them in later years. There is a room about the Japanese consul who in defiance of his government provided six thousand Jews with exit visas. There is a room about “Lithuanians, the Saviours of the Jews,” with stories of Lithuanian Gentiles who hid or helped their Jewish neighbors. And there is a room about Hitler and the genocide of European Jews, with names of 1,344 Jews from various parts of Europe who were killed here, each with their age and home town. Jutta and Gustl were not included – I looked for them, and the omission bothered me. But to continue…

At the back of that room is a curtain, and if you go through there is a smaller room with a film showing the testimony of eight Lithuanian soldiers who were sentenced to death by the Soviet government in 1962 for participating in Nazi-organized massacres. One mimes standing at the edge of the mass graves and shooting down into the crowds of people, and explains how he would sell items he picked off the victims to buy a drink afterwards because “when you do such kind of thing you need to wet your whistle.”

At the back of that room is a curtain, and if you go through there is a smaller room with a film showing the testimony of eight Lithuanian soldiers who were sentenced to death by the Soviet government in 1962 for participating in Nazi-organized massacres. One mimes standing at the edge of the mass graves and shooting down into the crowds of people, and explains how he would sell items he picked off the victims to buy a drink afterwards because “when you do such kind of thing you need to wet your whistle.”

I was in that section for fifteen minutes, and maybe two dozen people wandered through the first room, looked at the photos, looked at the quotations from Hitler, looked at the wall of names. Only a couple pulled back the curtain, and not one bothered to watch the film. I understand; there was a lot to see and watching a film takes time. Not one plaque or label anywhere else mentioned that Lithuanians were involved in any of the Nazi murders. I was taking note, because in the Vilnius genocide museum they use the same technique: the room on the Nazi period includes a video that mentions Lithuanian involvement in the murder of Jews, but you have to watch the video to get that information – the texts and wall displays do not even hint at that possibility.

I’m not trying to make a point about the Lithuanians. I mentioned an Israeli historian above, and US historians, and my point is how nationalists construct national narratives. Some are more subtle than others, but the process is pretty general.

At the Ninth Fort there are memorial stones placed by the city of Frankfurt in memory of the Jews transported from there to Kaunas; by the families and friends of the Jews transported and killed from France; by the city of Berlin in memory of the thousand Jewish children, women and men transported on Nov 17, 1941 and killed here on Nov 25; by the city of Munich in memory of the thousand Jews transported from there on November 20, 1941, and killed here five days later. There is no stone from Austria or from the city of Vienna to commemorate the transport on November 23 that included my cousins. Like the Lithuanians, the Austrians prefer to recall the Nazi period as their own tragedy, not a Jewish tragedy. They do not deny that Jews were particularly selected for extermination, but they have their own issues, and feel we must remember it was a tough time, and everybody suffered…

At the Ninth Fort there are memorial stones placed by the city of Frankfurt in memory of the Jews transported from there to Kaunas; by the families and friends of the Jews transported and killed from France; by the city of Berlin in memory of the thousand Jewish children, women and men transported on Nov 17, 1941 and killed here on Nov 25; by the city of Munich in memory of the thousand Jews transported from there on November 20, 1941, and killed here five days later. There is no stone from Austria or from the city of Vienna to commemorate the transport on November 23 that included my cousins. Like the Lithuanians, the Austrians prefer to recall the Nazi period as their own tragedy, not a Jewish tragedy. They do not deny that Jews were particularly selected for extermination, but they have their own issues, and feel we must remember it was a tough time, and everybody suffered…

Which is true enough, in its way. The Ninth Fort museum even has  one photograph that, if you take the trouble to read the small print on its caption, turns out to show “the exhumation of remains of Soviet prisoners of war.” They aren’t denying there were Russians killed in the Nazi period. If asked, I’m sure they would acknowledge that the Nazis killed millions of Soviet citizens, including some in Lithuania. That’s just not the story this museum is here to tell.

one photograph that, if you take the trouble to read the small print on its caption, turns out to show “the exhumation of remains of Soviet prisoners of war.” They aren’t denying there were Russians killed in the Nazi period. If asked, I’m sure they would acknowledge that the Nazis killed millions of Soviet citizens, including some in Lithuania. That’s just not the story this museum is here to tell.

History is always an effort to preserve and remember what is important from the past, which always requires selecting what is important, which always means what is important to us, whoever we may be. But here I am writing specifically about how national histories are framed to suit nationalist needs, defining a national “us” and making us feel good about being part of that “us.”

One of the most powerful ways of creating a unified “us” is by recalling the terrible things other people did to us, and how we survived and overcame those trials. That often requires a bit of creative amnesia, since other people frequently have horror stories in which we were the perpetrators. One technique is simply to deny the ugly parts; others are more subtle, acknowledging that crimes were committed, but framing them in ways that make them seem less ugly, or just less meaningful, or less visceral.

In the last few weeks I’ve visited Auschwitz and Majdanek, where far more people were killed than at the Ninth Fort, but neither of those visits hit me as hard as this one. Because this one is personal: I have the photo, the names, the dates, and my mother’s memories of Jutta, the story of why she and her mother remained in Vienna, and the record of their transportation to Kaunas and their murder. I’m telling some of that story here, and plan to write more about it, because individual stories are powerful.

The people making these museums understand that. Their displays are full of individual heroes and martyrs. And, looked at another way, full of absences.

*In response to years of protests, the Vilnius museum has officially been renamed the Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights, but all its signage still says the Museum of Genocide Victims.

This particular mosque apparently dates from the 18th century, but the community that built it has been in the region since the mid-17th century. They are Tatars, descendants of the Golden Horde that reached Eastern Europe shortly after the death of Genghis Khan. Since I’m traveling here as part of a project on borders and migration, and in particular looking into my own family’s history, when I read about the Tatars I immediately wondered what happened to them during the Nazi occupation.

This particular mosque apparently dates from the 18th century, but the community that built it has been in the region since the mid-17th century. They are Tatars, descendants of the Golden Horde that reached Eastern Europe shortly after the death of Genghis Khan. Since I’m traveling here as part of a project on borders and migration, and in particular looking into my own family’s history, when I read about the Tatars I immediately wondered what happened to them during the Nazi occupation. Robertson also writes that the Tatar Mufti of Poland, Jacob Szynkiewicz, helped protect the Karaite Jews by calling Goebbels to make the case that they were racially Turkic. I haven’t found corroboration of that particular story, but there is plenty of evidence that the Nazis considered the Karaim related to the Tatars both by ancestry and as communities that interacted on a regular basis – and therefore (except in a few notable instances) did not subject them to ghettoization or extermination. As a result, some Jews – meaning Ashkenazim – also managed to survive the holocaust by passing as Jews – meaning Karaim.

Robertson also writes that the Tatar Mufti of Poland, Jacob Szynkiewicz, helped protect the Karaite Jews by calling Goebbels to make the case that they were racially Turkic. I haven’t found corroboration of that particular story, but there is plenty of evidence that the Nazis considered the Karaim related to the Tatars both by ancestry and as communities that interacted on a regular basis – and therefore (except in a few notable instances) did not subject them to ghettoization or extermination. As a result, some Jews – meaning Ashkenazim – also managed to survive the holocaust by passing as Jews – meaning Karaim. tour of the mosque in Kruszyniany was conducted entirely in Polish, so I understood virtually nothing, but I did catch the words, “Charles Bronson…Charles Buchinski.” I assumed the guide was claiming Bronson as a Tatar, so checked and found that yes, indeed, his father was apparently a Tatar from Lithuania, and this touch of Mongolian heritage presumably was what made him so easy to cast as a Native American…

tour of the mosque in Kruszyniany was conducted entirely in Polish, so I understood virtually nothing, but I did catch the words, “Charles Bronson…Charles Buchinski.” I assumed the guide was claiming Bronson as a Tatar, so checked and found that yes, indeed, his father was apparently a Tatar from Lithuania, and this touch of Mongolian heritage presumably was what made him so easy to cast as a Native American… On a more serious note, the Tatars have recently been caught up in the anti-Muslim violence sweeping Europe. A mosque built by Tatars in Gdansk in the 1990s was firebombed in 2013, and in 2014 the historic mosque and cemetery I visited in Krusziniany were defaced with anti-Muslim slogans and a drawing of a pig. Which is ugly, and the ugliness is underlined by a story in the New York Times that quotes local Tatars blaming the violence on the influx of Muslim immigrants, which they see as raising justifiable concern among Poles that is causing friction where none existed before.

On a more serious note, the Tatars have recently been caught up in the anti-Muslim violence sweeping Europe. A mosque built by Tatars in Gdansk in the 1990s was firebombed in 2013, and in 2014 the historic mosque and cemetery I visited in Krusziniany were defaced with anti-Muslim slogans and a drawing of a pig. Which is ugly, and the ugliness is underlined by a story in the New York Times that quotes local Tatars blaming the violence on the influx of Muslim immigrants, which they see as raising justifiable concern among Poles that is causing friction where none existed before. , two of the five synagogues are even still there… but the synagogues are abandoned and boarded up, because the Jews who used to be almost a third of the population are not there anymore, nor are their descendants… and same in Lesko, where 70% of the town used to be Jewish, and now the only remaining synagogue is an art gallery, and much of the art is Christs and Madonnas and saints… and I recently posted a funny story about

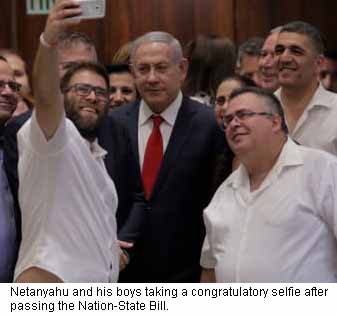

, two of the five synagogues are even still there… but the synagogues are abandoned and boarded up, because the Jews who used to be almost a third of the population are not there anymore, nor are their descendants… and same in Lesko, where 70% of the town used to be Jewish, and now the only remaining synagogue is an art gallery, and much of the art is Christs and Madonnas and saints… and I recently posted a funny story about  Nation-State Bill, which says “the right to national self-determination in Israel is unique to the Jewish people” — which is another way of saying if you are an Arab Israeli, you may live there but it is not your country.

Nation-State Bill, which says “the right to national self-determination in Israel is unique to the Jewish people” — which is another way of saying if you are an Arab Israeli, you may live there but it is not your country.

skansen reflects the multi-cultural nature of rural Galicia in 1900, with sections showing the lifestyles of the Eastern Orthodox Boyks and Lemks, the Catholic (now often called “ethnic”) Poles… and a large wooden synagogue and two “Jewish” houses on the main square.

skansen reflects the multi-cultural nature of rural Galicia in 1900, with sections showing the lifestyles of the Eastern Orthodox Boyks and Lemks, the Catholic (now often called “ethnic”) Poles… and a large wooden synagogue and two “Jewish” houses on the main square. He spoke some English, and enthusiastically showed us around: the bedroom, for example, where he pointed out the curling iron for shaping the men’s peyos and the peculiarity of the marital bed, which could be separated when the Jewish woman had her period or had given birth, hence was “unclean,” and pushed together again after she had bathed in the mikveh. He showed us the special dishes for meat and dairy, and the sabbath dishes. All very strange and exotic…

He spoke some English, and enthusiastically showed us around: the bedroom, for example, where he pointed out the curling iron for shaping the men’s peyos and the peculiarity of the marital bed, which could be separated when the Jewish woman had her period or had given birth, hence was “unclean,” and pushed together again after she had bathed in the mikveh. He showed us the special dishes for meat and dairy, and the sabbath dishes. All very strange and exotic…

nk, in Jordan, in refugee camps, and in a global diaspora. Some have famously kept the keys to the houses they or their grandparents left – the key has become a symbol of Palestinian return; some tell stories of visiting Haifa in later years, knocking on the doors of their houses and asking the Jewish owners if they could walk through the rooms, see if their family pictures were still on the walls, their rugs still on the floors; others have never set foot in Israel and talk longingly of visiting the places they heard of from their parents or grand-parents.

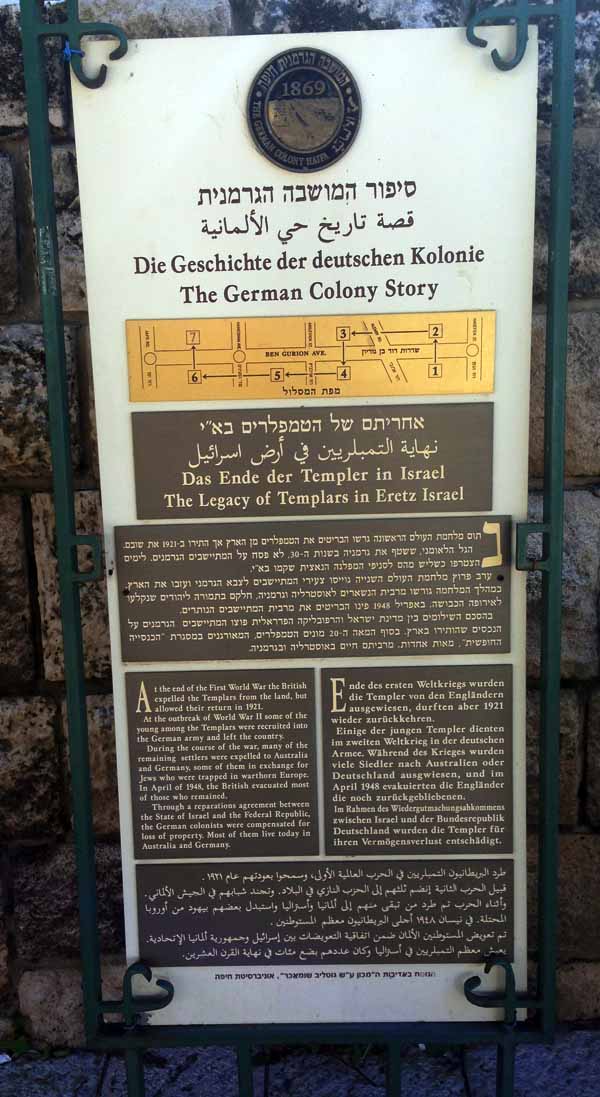

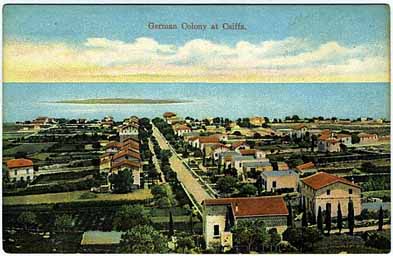

nk, in Jordan, in refugee camps, and in a global diaspora. Some have famously kept the keys to the houses they or their grandparents left – the key has become a symbol of Palestinian return; some tell stories of visiting Haifa in later years, knocking on the doors of their houses and asking the Jewish owners if they could walk through the rooms, see if their family pictures were still on the walls, their rugs still on the floors; others have never set foot in Israel and talk longingly of visiting the places they heard of from their parents or grand-parents. Which is why I was startled by an informational sign on Ben Gurion Avenue in Haifa telling “Die Geschichte der deutschen Kolonie/The German Colony Story,” and in particular about the Templars, a German Protestant group that settled there in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Which is why I was startled by an informational sign on Ben Gurion Avenue in Haifa telling “Die Geschichte der deutschen Kolonie/The German Colony Story,” and in particular about the Templars, a German Protestant group that settled there in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Karl Ruff, an architect born to Templar parents in Haifa in 1904, made contact with the German Nazis in 1931, two years before Hitler came to power, and helped form a core of support that grew into a full-blown Palestinian branch by 1933. A year later, Ludwig Buchhalter, a teacher at the Templar school in Jerusalem, was active in getting the German consul removed from office for having a Jewish wife, arguing “a person who has relations with Jewish circles cannot be loyal to German interests…”

Karl Ruff, an architect born to Templar parents in Haifa in 1904, made contact with the German Nazis in 1931, two years before Hitler came to power, and helped form a core of support that grew into a full-blown Palestinian branch by 1933. A year later, Ludwig Buchhalter, a teacher at the Templar school in Jerusalem, was active in getting the German consul removed from office for having a Jewish wife, arguing “a person who has relations with Jewish circles cannot be loyal to German interests…” The Templar colony of Sarona, established in 1871 just north of the Arab city of Jaffa, preceded the first Jewish settlement in what is now Tel Aviv and pioneered the export of Jaffa oranges. Now a thriving, upscale neighborhood, Sarona has a museum tracing the history of the German settlement, which includes a room devoted to the Nazi period, but also photos and memorabilia of the early German colonists, their lovely houses, and their fertile farms.

The Templar colony of Sarona, established in 1871 just north of the Arab city of Jaffa, preceded the first Jewish settlement in what is now Tel Aviv and pioneered the export of Jaffa oranges. Now a thriving, upscale neighborhood, Sarona has a museum tracing the history of the German settlement, which includes a room devoted to the Nazi period, but also photos and memorabilia of the early German colonists, their lovely houses, and their fertile farms. In the middle of a sparsely populated and largely barren land, laboring under deficient rule, hundreds of German settlers characterized by great energy, resourcefulness, religious fervor and a variety of professional backgrounds, established a garden city unlike any that existed in the country until then. Outside the Haifa city walls, a boulevard sprang up stretching from the foot of the hills to the sea. It was lined with gardens and homes, remarkable for their beauty.

In the middle of a sparsely populated and largely barren land, laboring under deficient rule, hundreds of German settlers characterized by great energy, resourcefulness, religious fervor and a variety of professional backgrounds, established a garden city unlike any that existed in the country until then. Outside the Haifa city walls, a boulevard sprang up stretching from the foot of the hills to the sea. It was lined with gardens and homes, remarkable for their beauty. Israel and Germany are now allies, Haifa is celebrated as a model of multicultural coexistence, and those markers in the heart of the old port provide a nice history to match its current image: once largely barren and sparsely populated, Haifa was settled by industrious Germans who founded a unique garden city, planted vineyards and olive groves, created new industries, and built a power station and a regional transport system. In 1902 Theodor Herzl’s utopian novel, Altneuland, envisioned this European outpost as the economic center of a future land of Israel, and it soon became a magnet for Jewish settlement. Eventually global politics forced the Germans to leave, but they were paid proper compensation and Haifa today is a lovely, cosmopolitan center, a perfect blend of European civilization and Middle Eastern charm. The Arab population remains relatively sparse numerically, but continues to thrive, a vibrant community with popular nightclubs, restaurants, and a rich arts scene.

Israel and Germany are now allies, Haifa is celebrated as a model of multicultural coexistence, and those markers in the heart of the old port provide a nice history to match its current image: once largely barren and sparsely populated, Haifa was settled by industrious Germans who founded a unique garden city, planted vineyards and olive groves, created new industries, and built a power station and a regional transport system. In 1902 Theodor Herzl’s utopian novel, Altneuland, envisioned this European outpost as the economic center of a future land of Israel, and it soon became a magnet for Jewish settlement. Eventually global politics forced the Germans to leave, but they were paid proper compensation and Haifa today is a lovely, cosmopolitan center, a perfect blend of European civilization and Middle Eastern charm. The Arab population remains relatively sparse numerically, but continues to thrive, a vibrant community with popular nightclubs, restaurants, and a rich arts scene. Colonial Exhibition of 1931. The facade of this building, which first housed the Musée des Colonies, is a huge cement bas-relief of scenes from “greater France” — elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers, temples, sailing ships, and toiling or warlike natives of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, set off with mentions of what each area has contributed to the mother country: rice, rubber, cotton, tea…

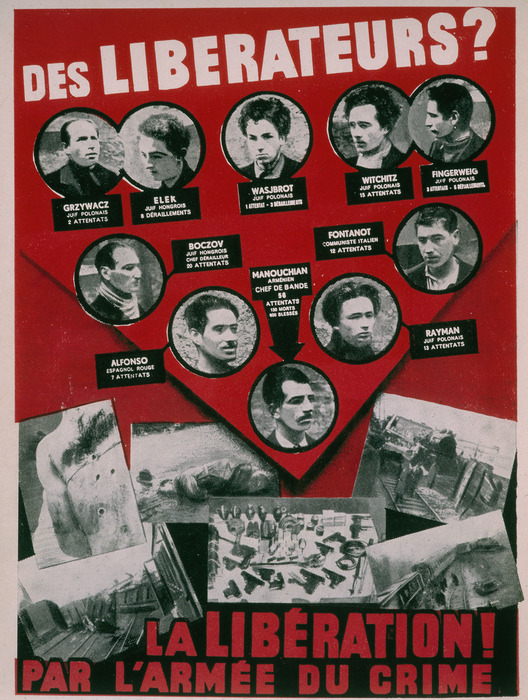

Colonial Exhibition of 1931. The facade of this building, which first housed the Musée des Colonies, is a huge cement bas-relief of scenes from “greater France” — elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers, temples, sailing ships, and toiling or warlike natives of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, set off with mentions of what each area has contributed to the mother country: rice, rubber, cotton, tea… foreigner highlighted on the timeline is Frédéric Chopin, arriving in 1831 “like numerous intellectual, military, political, and artistic Polish insurgents after the failed revolt against the power of the Czar.”

foreigner highlighted on the timeline is Frédéric Chopin, arriving in 1831 “like numerous intellectual, military, political, and artistic Polish insurgents after the failed revolt against the power of the Czar.” This affair notably split French intellectuals and artists, with Degas (a particularly vicious anti-Semite), Renoir, and Cézanne expressing their distaste for the “foreigners” — so denominated though some Jewish families had been in France for many generations — while Monet and Mary Cassatt lined up on the other side, along with Pissarro, who was Jewish, born in the Danish West Indies, and sometimes bore the brunt of his colleagues’ prejudice.

This affair notably split French intellectuals and artists, with Degas (a particularly vicious anti-Semite), Renoir, and Cézanne expressing their distaste for the “foreigners” — so denominated though some Jewish families had been in France for many generations — while Monet and Mary Cassatt lined up on the other side, along with Pissarro, who was Jewish, born in the Danish West Indies, and sometimes bore the brunt of his colleagues’ prejudice.

I’m not trying to recap the whole museum — a five-hour visit was not sufficient to explore its range and depth — but a couple more details are worth mentioning. One is the charming irony that the most familiar evocation of an indigenous French heritage, the comic book adventures of Asterix, Obelix, and their fellow Gauls holding out against the Roman Empire, was created by a pair of second-generation immigrants: Alberto Uderzo, whose parents immigrated from Italy shortly before his birth, and René Goscinny, the son of Polish Jews.

I’m not trying to recap the whole museum — a five-hour visit was not sufficient to explore its range and depth — but a couple more details are worth mentioning. One is the charming irony that the most familiar evocation of an indigenous French heritage, the comic book adventures of Asterix, Obelix, and their fellow Gauls holding out against the Roman Empire, was created by a pair of second-generation immigrants: Alberto Uderzo, whose parents immigrated from Italy shortly before his birth, and René Goscinny, the son of Polish Jews. that visitors should be inspired to donate material about their own immigrant families and history in France, among the donations is a baby-foot table (what Americans call foosball and other Anglophones table football) made by the Bonzini family, descendants of Italian immigrants who are one of the main French manufacturers. The Bonzinis originally donated the table for an exhibition called

that visitors should be inspired to donate material about their own immigrant families and history in France, among the donations is a baby-foot table (what Americans call foosball and other Anglophones table football) made by the Bonzini family, descendants of Italian immigrants who are one of the main French manufacturers. The Bonzinis originally donated the table for an exhibition called

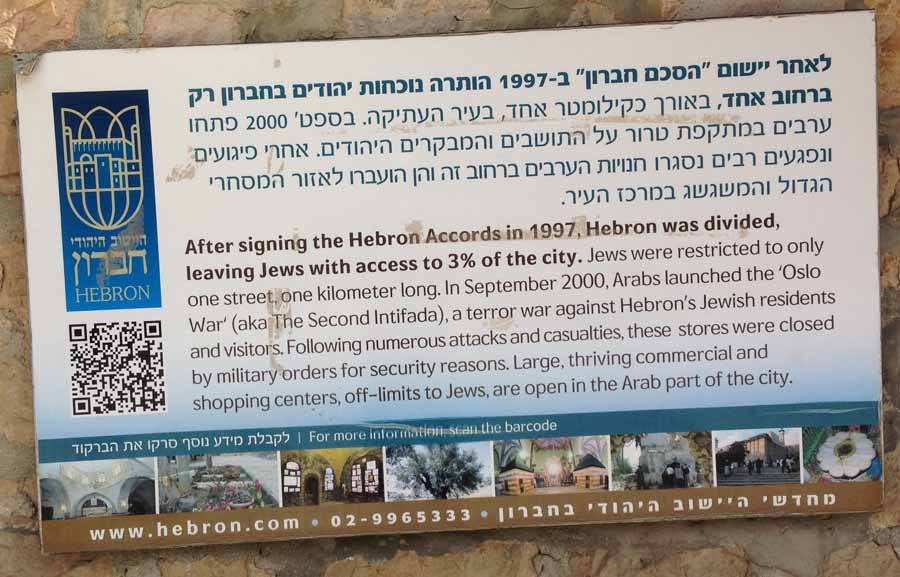

I put the word “Jews” in quotation marks because in this instance I’m quoting a particular sign I photographed, which describes the city’s “large, thriving commercial and shopping centers, off-limits to Jews…” The stress on “large” and “thriving” underlines the point that, although 3% of Hebron’s physical area — the urban center of the southern West Bank — is off-limits to the city’s 200,000 Palestinian residents (both Muslim and Christian), with checkpoints manned by soldiers to enforce that prohibition, the remaining 97% of the city is open to Palestinians and off-limits to Jews…

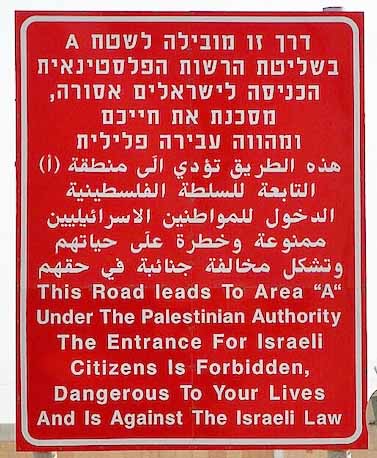

I put the word “Jews” in quotation marks because in this instance I’m quoting a particular sign I photographed, which describes the city’s “large, thriving commercial and shopping centers, off-limits to Jews…” The stress on “large” and “thriving” underlines the point that, although 3% of Hebron’s physical area — the urban center of the southern West Bank — is off-limits to the city’s 200,000 Palestinian residents (both Muslim and Christian), with checkpoints manned by soldiers to enforce that prohibition, the remaining 97% of the city is open to Palestinians and off-limits to Jews… divisions: the West Bank is often described as Palestinian territory, but only the urban areas, comprising a bit less than 20% of the total land, are under direct Palestinian control. Those are the scattered pockets classified as Area A, which Israelis are forbidden to enter (except soldiers, who enter them daily to conduct raids and arrests). Area B, accounting for another 20% of the West Bank, includes smaller Palestinian towns and villages, and is under Palestinian civil control with joint Palestinian/Israeli police/military control, and likewise barred to Israelis. The remaining 60% (actually, a bit more) is under full Israeli civil and military control; this includes the settlements, virtually all the unsettled countryside, and most of the main roads, all of which are open to Israelis – hence the signs at highway exits leading to any Palestinian city, town, or village warning Israeli drivers it is dangerous and illegal to go there.

divisions: the West Bank is often described as Palestinian territory, but only the urban areas, comprising a bit less than 20% of the total land, are under direct Palestinian control. Those are the scattered pockets classified as Area A, which Israelis are forbidden to enter (except soldiers, who enter them daily to conduct raids and arrests). Area B, accounting for another 20% of the West Bank, includes smaller Palestinian towns and villages, and is under Palestinian civil control with joint Palestinian/Israeli police/military control, and likewise barred to Israelis. The remaining 60% (actually, a bit more) is under full Israeli civil and military control; this includes the settlements, virtually all the unsettled countryside, and most of the main roads, all of which are open to Israelis – hence the signs at highway exits leading to any Palestinian city, town, or village warning Israeli drivers it is dangerous and illegal to go there. When I mentioned to friends in the United States that I was headed there, many warned me to be careful — the West Bank is only mentioned in the US media when there is violence, so we associate it with violence. When I mentioned my plans to Jewish Israelis, the reactions were more varied: some were concerned about my safety, some puzzled why I wanted to go, some curious to hear what it is like, some irritated that I would expect to learn something about the region on a short visit — with the assumption I would come away more critical of Israeli policies — some encouraging me and saying they wished they could go there as well.

When I mentioned to friends in the United States that I was headed there, many warned me to be careful — the West Bank is only mentioned in the US media when there is violence, so we associate it with violence. When I mentioned my plans to Jewish Israelis, the reactions were more varied: some were concerned about my safety, some puzzled why I wanted to go, some curious to hear what it is like, some irritated that I would expect to learn something about the region on a short visit — with the assumption I would come away more critical of Israeli policies — some encouraging me and saying they wished they could go there as well. seeing someplace new, having a vacation. The Lonely Planet guidebook to Israel and the Palestinian Territories begins the relevant section on cheerful note:

seeing someplace new, having a vacation. The Lonely Planet guidebook to Israel and the Palestinian Territories begins the relevant section on cheerful note: I recommend any traveler visiting Israel spend some time on the West Bank — not just a day-trip to Bethlehem, but staying a while, going to nightclubs in Ramallah, exploring the old city of Nablus, visiting the Freedom Theater in Jenin, or hiking around the Jordan Valley — and be assured, there are plenty of other travelers making those trips (women as well as men, often on their own), and having a wonderful time.

I recommend any traveler visiting Israel spend some time on the West Bank — not just a day-trip to Bethlehem, but staying a while, going to nightclubs in Ramallah, exploring the old city of Nablus, visiting the Freedom Theater in Jenin, or hiking around the Jordan Valley — and be assured, there are plenty of other travelers making those trips (women as well as men, often on their own), and having a wonderful time. My first night in Ramallah, I got in a long discussion with Nidal Abu Maria, who owns

My first night in Ramallah, I got in a long discussion with Nidal Abu Maria, who owns  That choice is notable because France is not “normal” in the sense of being typical; on the contrary, it has long been held up as an ideal, particularly for German-speaking Central Europeans who dreamed of living wie Gott in Frankreich (like God in France), and more particularly for Central European Jews: Joseph Roth, arriving in France via Vienna and Berlin in the interwar years, wrote, “Paris is where the Eastern Jew begins to become a Western European.”

That choice is notable because France is not “normal” in the sense of being typical; on the contrary, it has long been held up as an ideal, particularly for German-speaking Central Europeans who dreamed of living wie Gott in Frankreich (like God in France), and more particularly for Central European Jews: Joseph Roth, arriving in France via Vienna and Berlin in the interwar years, wrote, “Paris is where the Eastern Jew begins to become a Western European.” solution, a one-state solution, or even a nasty war — but, in any case, resolved. A lot of conversations in Israel reinforce that impression, but after a while I realized that if I didn’t steer the talk in that direction it needn’t go there and most Israelis could probably go for days without mentioning the Occupied Territories or any Palestinian conflict. Because, quite simply, it doesn’t affect their day-to-day life. Yes, they see soldiers all around, often carrying automatic rifles, but being in the army is a basic part of growing up for most Israelis, so they’re used to that. And it is easy to live within a few minutes walk of the wall that blocks off the West Bank and never see it, or ever talk to a Palestinian — or to talk to Palestinians, but not about that.

solution, a one-state solution, or even a nasty war — but, in any case, resolved. A lot of conversations in Israel reinforce that impression, but after a while I realized that if I didn’t steer the talk in that direction it needn’t go there and most Israelis could probably go for days without mentioning the Occupied Territories or any Palestinian conflict. Because, quite simply, it doesn’t affect their day-to-day life. Yes, they see soldiers all around, often carrying automatic rifles, but being in the army is a basic part of growing up for most Israelis, so they’re used to that. And it is easy to live within a few minutes walk of the wall that blocks off the West Bank and never see it, or ever talk to a Palestinian — or to talk to Palestinians, but not about that. but if you frame them as ways to reduce tension and let off steam while extending the wall, maintaining the checkpoints, expanding the settlements, ensuring the refugees in Lebanon and Jordan do not return, and carrying out daily raids, arrests, and frequently killings on the West Bank — that is, while keeping things the way they are — they feel not like progress but like ways of normalizing the status quo.

but if you frame them as ways to reduce tension and let off steam while extending the wall, maintaining the checkpoints, expanding the settlements, ensuring the refugees in Lebanon and Jordan do not return, and carrying out daily raids, arrests, and frequently killings on the West Bank — that is, while keeping things the way they are — they feel not like progress but like ways of normalizing the status quo. April 20, 2018:

April 20, 2018: about his arrest and upcoming trial as a member of the Harrisburg 7, one of the famous conspiracy trials of the Vietnam War era. His fellow defendants were all Catholic clergy, including Phillip Berrigan, and Eqbal often told how his mother called him when she heard the news, saying: “I can understand you being against the Vietnam war. I can even understand you being arrested for this. But what are you doing being arrested with a group of priests and nuns?!”

about his arrest and upcoming trial as a member of the Harrisburg 7, one of the famous conspiracy trials of the Vietnam War era. His fellow defendants were all Catholic clergy, including Phillip Berrigan, and Eqbal often told how his mother called him when she heard the news, saying: “I can understand you being against the Vietnam war. I can even understand you being arrested for this. But what are you doing being arrested with a group of priests and nuns?!” was telling stories of his youth — that was the only time I heard him talk about seeing his father killed when he was a small boy, hiding behind his father’s legs as the killers attacked, and about fighting in Kashmir. My parents eventually drifted off to bed, but I stayed up, sixteen years old and enthralled. He talked about his student days in Paris, meeting young revolutionaries from around the world. He was particularly struck by the Algerian students who were going home to fight with the

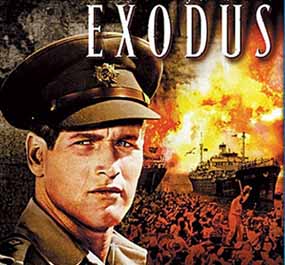

was telling stories of his youth — that was the only time I heard him talk about seeing his father killed when he was a small boy, hiding behind his father’s legs as the killers attacked, and about fighting in Kashmir. My parents eventually drifted off to bed, but I stayed up, sixteen years old and enthralled. He talked about his student days in Paris, meeting young revolutionaries from around the world. He was particularly struck by the Algerian students who were going home to fight with the  There are other stories, but at the moment I keep coming back to that image of Exodus. Partly because I watched the movie in preparation for my trip to Israel/Palestine and recently wrote about

There are other stories, but at the moment I keep coming back to that image of Exodus. Partly because I watched the movie in preparation for my trip to Israel/Palestine and recently wrote about  I saw Eqbal more rarely in later years. He founded a university in Pakistan and was there much of the time, while I was touring as a musician and writing for the Boston Globe, so one way and another our paths didn’t cross. Our last meeting was at his retirement from Hampshire College, where he had taught for some years. Edward Said and Howard Zinn were there, among many others, and I spoke briefly about Eqbal’s cooking. At the party afterwards he asked me to come to Pakistan and work with him, and I’ll always wonder if he was serious about that, and how my life might have been different if he was and I’d gone.

I saw Eqbal more rarely in later years. He founded a university in Pakistan and was there much of the time, while I was touring as a musician and writing for the Boston Globe, so one way and another our paths didn’t cross. Our last meeting was at his retirement from Hampshire College, where he had taught for some years. Edward Said and Howard Zinn were there, among many others, and I spoke briefly about Eqbal’s cooking. At the party afterwards he asked me to come to Pakistan and work with him, and I’ll always wonder if he was serious about that, and how my life might have been different if he was and I’d gone. “What terms of entry may we impose on the immigrant without infringing on his inalienable rights, as defined in our national charter?” Mary Antin asked in 1914. Her answer:

“What terms of entry may we impose on the immigrant without infringing on his inalienable rights, as defined in our national charter?” Mary Antin asked in 1914. Her answer: When I was a little girl, the world was divided into two parts; namely, Polotzk, the place where I lived, and a strange land called Russia. All the little girls I knew lived in Polotzk, with their fathers and mothers and friends. Russia was the place where one’s father went on business. It was so far off, and so many bad things happened there, that one’s mother and grandmother and grown-up aunts cried at the railroad station…

When I was a little girl, the world was divided into two parts; namely, Polotzk, the place where I lived, and a strange land called Russia. All the little girls I knew lived in Polotzk, with their fathers and mothers and friends. Russia was the place where one’s father went on business. It was so far off, and so many bad things happened there, that one’s mother and grandmother and grown-up aunts cried at the railroad station… Antin was an ardent believer in the ideals exemplified by Lazarus’s poem and The Declaration of Independence, and as an activist for women’s education and immigrant rights she fought to make her fellow citizens live up to them. When her memoir became a best-seller, she followed with a book-length polemic:

Antin was an ardent believer in the ideals exemplified by Lazarus’s poem and The Declaration of Independence, and as an activist for women’s education and immigrant rights she fought to make her fellow citizens live up to them. When her memoir became a best-seller, she followed with a book-length polemic:  citizenship and solid nation-state borders were still in their infancy, and modern readers will find her next passage surprising:

citizenship and solid nation-state borders were still in their infancy, and modern readers will find her next passage surprising: Some people see no indication of the future in the fact that race-blending has been going on here from the beginning of our history, because the elements we now get are said to differ from us more radically than the elements we assimilated in the past. To allay our anxiety on this point, we have only to remind ourselves that none of the great nations of Europe that present such a homogeneous front to-day arose from a single stock…

Some people see no indication of the future in the fact that race-blending has been going on here from the beginning of our history, because the elements we now get are said to differ from us more radically than the elements we assimilated in the past. To allay our anxiety on this point, we have only to remind ourselves that none of the great nations of Europe that present such a homogeneous front to-day arose from a single stock… article quoting her upbraiding immigrant bosses for forgetting their roots and mistreating striking garment workers.

article quoting her upbraiding immigrant bosses for forgetting their roots and mistreating striking garment workers.