In the Jewish settler area of Hebron, an apparent ghost town of closed shops, houses populated by Palestinians who are forbidden to use their front doors or drive on the streets, and Israelis who seem to live almost entirely indoors or in walled courtyards, a series of informative signs trace the history and current situation of “Jews” in Hebron.

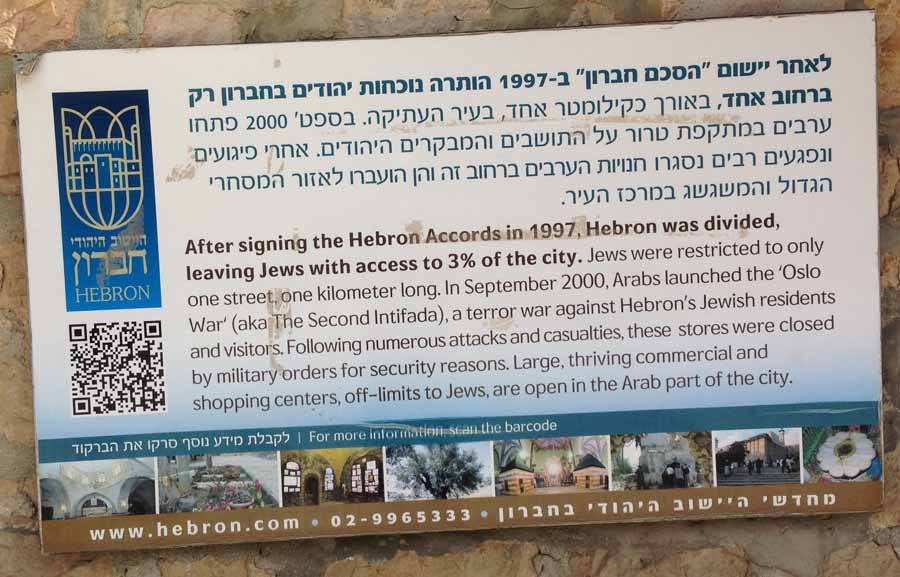

I put the word “Jews” in quotation marks because in this instance I’m quoting a particular sign I photographed, which describes the city’s “large, thriving commercial and shopping centers, off-limits to Jews…” The stress on “large” and “thriving” underlines the point that, although 3% of Hebron’s physical area — the urban center of the southern West Bank — is off-limits to the city’s 200,000 Palestinian residents (both Muslim and Christian), with checkpoints manned by soldiers to enforce that prohibition, the remaining 97% of the city is open to Palestinians and off-limits to Jews…

I put the word “Jews” in quotation marks because in this instance I’m quoting a particular sign I photographed, which describes the city’s “large, thriving commercial and shopping centers, off-limits to Jews…” The stress on “large” and “thriving” underlines the point that, although 3% of Hebron’s physical area — the urban center of the southern West Bank — is off-limits to the city’s 200,000 Palestinian residents (both Muslim and Christian), with checkpoints manned by soldiers to enforce that prohibition, the remaining 97% of the city is open to Palestinians and off-limits to Jews…

…except, in fact, it isn’t off-limits to Jews. Like all the other Palestinian cities, which are classified as “Area A,”1 most of Hebron is off-limits to Israelis, but open to Jews of all other nationalities — along with Muslims, Christians, Samaritans, atheists, and people of any other faith, or lack of faith. I was staying in a hotel in the thriving city center, eating in crowded restaurants, wandering the bustling streets, being importuned by eager merchants — and no one ever suggested that my being Jewish was an issue.

Even when a pair of Israeli soldiers stopped me at a checkpoint, asked my religion, and refused to let me pass because I was Jewish, they were preventing me from walking down the one-block, non-commercial street in front of the Ibrahimi mosque and directing me to go around by side streets to the city center.

The misleading wordplay is not the only problem with this sign — the elision of the city’s most famous terrorist attack, by a Jewish gunman at the mosque, might take precedence there2 — but I found it particularly striking because it so clearly conflicted with my own experience. By the time I reached Hebron I’d been on the West Bank for a week, talking with lots of people, including ardent Palestinian nationalists, and routinely identifying myself as Jewish (because I didn’t want anyone to think I was hiding that detail). Without exception, everyone responded that their problem was with Israelis or with Zionists, but not with Jews – as always in Muslim countries, I was treated to explanations of how Muslims, Jews, and Christians are all “people of the book,” and since this region has a particularly strong consciousness of the three religions’ historical coexistence, I was regaled with stories of Jewish friends and neighbors and in a couple of cases of Jewish relatives. So I was intensely aware that simply being Jewish does not get anyone barred from Palestinian cities.

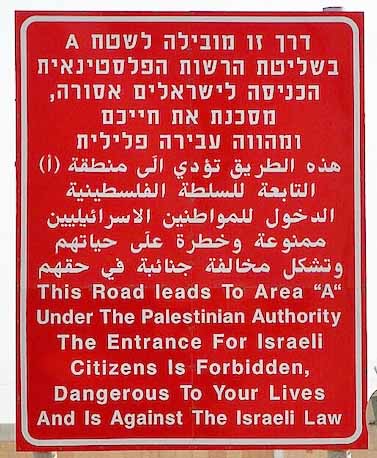

There’s plenty more to be said about all of that, but for a start it got me thinking about the ubiquitous signs marking entrances to “Area A.” For people unfamiliar with the region’s odd  divisions: the West Bank is often described as Palestinian territory, but only the urban areas, comprising a bit less than 20% of the total land, are under direct Palestinian control. Those are the scattered pockets classified as Area A, which Israelis are forbidden to enter (except soldiers, who enter them daily to conduct raids and arrests). Area B, accounting for another 20% of the West Bank, includes smaller Palestinian towns and villages, and is under Palestinian civil control with joint Palestinian/Israeli police/military control, and likewise barred to Israelis. The remaining 60% (actually, a bit more) is under full Israeli civil and military control; this includes the settlements, virtually all the unsettled countryside, and most of the main roads, all of which are open to Israelis – hence the signs at highway exits leading to any Palestinian city, town, or village warning Israeli drivers it is dangerous and illegal to go there.

divisions: the West Bank is often described as Palestinian territory, but only the urban areas, comprising a bit less than 20% of the total land, are under direct Palestinian control. Those are the scattered pockets classified as Area A, which Israelis are forbidden to enter (except soldiers, who enter them daily to conduct raids and arrests). Area B, accounting for another 20% of the West Bank, includes smaller Palestinian towns and villages, and is under Palestinian civil control with joint Palestinian/Israeli police/military control, and likewise barred to Israelis. The remaining 60% (actually, a bit more) is under full Israeli civil and military control; this includes the settlements, virtually all the unsettled countryside, and most of the main roads, all of which are open to Israelis – hence the signs at highway exits leading to any Palestinian city, town, or village warning Israeli drivers it is dangerous and illegal to go there.

Or maybe that should be “Israeli” drivers…

As I rode buses around the West Bank, I noticed that highway exits routinely have these signs warning Israelis that entering Area A is “dangerous to your lives” and “against the Israeli law” and many exits have checkpoints manned by soldiers controlling who can pass – but they are rarely if ever the same exits. The military checkpoints are at exits leading to Jewish settlements, to prevent Palestinians from taking those roads, while nothing but the signs prevents Israelis from entering areas A and B.

Since anyone could simply drive past the signs and no one ever checked my identification papers while traveling in the West Bank, I began asking Israelis if they bothered to follow the rules. At first I was asking Jewish Israelis, and overwhelmingly they said they did. Even the activists of Machsom [Checkpoint] Watch said they tended to stay in the areas allowed to them, and I was given to understand that only the most radical leftists traverse the boundaries…

…but then I was in Nazareth, a city of non-Jewish Israelis (variously identifying as Arab Israelis or Palestinian Israelis), and got to talking with a young woman who mentioned that everyone goes shopping in Jenin, the northernmost West Bank city, which is less than thirty kilometers away, because prices are much lower than in Israel.

Now, Israel prides itself on being a democracy with the same laws for all citizens, whatever their religion. And yes, I’d always taken that with several grains of salt, but I still assumed the official signs saying it was illegal for Israelis to go into Area A meant it was illegal for Israelis to go there – not just Israeli Jews. So I asked, “Isn’t it illegal for Israelis to go to the West Bank?”

“Oh, they don’t care if we go there,” the young woman replied. Then she laughed, and added: “They’d prefer if we’d all go there and stay.”

I took this to mean the laws were enforced selectively or capriciously – a familiar concept, by no means only in Israel – and the signs saying it is illegal for Israelis to enter Area A were routinely flouted by Arab/Palestinian Israelis… until I was doing some background research for this post and stumbled on B’Tselem’s checkpoint page, which includes the regulations for Jalameh checkpoint between Nazareth and Jenin – and read that crossing at Jalameh is forbidden “to Israelis, with the exception of Palestinians who are Israeli citizens.”

So… that suggests Israeli Arabs/Palestinians are in fact allowed into the areas where Israeli Jews are barred. And indeed, that’s the de facto situation… which shouldn’t be confused with de jure. A recent article in Haaretz says Israeli Arabs make up more than half the enrollment at the Arab American University of Jenin (among some 8,000 studying in West Bank universities) and there is a regular bus system between the campus and their homes in northern Israel. Which seems pretty official, until a note confirms what the young woman told me in Nazareth: “Officially, Israelis are prohibited from entering Area A, but the Israel Defense Forces does not enforce the ban when it comes to Arab citizens.”

Hence, the tale of two signs in the looking-glass world of the West Bank: one saying “Jews,” though in practice it only means Israelis; the other saying “Israelis,” though in practice it only means Jews.

- Though all the other West Bank cities are in Area A, Hebron is a special case, divided into areas H1, which is essentially Area A and has a population of about 160,000 people, and H2, which is under full Israeli military control and includes the specifically Jewish areas and the rest of the old city, with a population of roughly 800 Jews and 40,000 Palestinians, who live there but are not allowed to drive in the streets and in many instances have had their street doors welded shut for “security” reasons. (If you do the math, you might note that although the sign I photographed makes the point that only 3% of the city is open to Jews, suggesting they are being limited to a tiny corner, it does not mention that they are less than 0.5% of the city’s population.)

- The sign’s reference to the Second Intifada as “the Oslo War” is another interesting bit of linguistic legerdemain: the Oslo accords were signed in 1993 and 1995; Baruch Goldstein’s killing of 29 Muslims in the Hebron mosque was in 1994; the rules dividing Hebron into Jewish and non-Jewish sections were imposed in 1997; and the Second Intifada began in 2000. Thus, the term “Oslo War” is not intended to indicate that the Second Intifada was contemporary with the Oslo accords, but rather that the process of recognizing the PLO and a pathway toward an independent Palestinian state led inevitably to Palestinian attacks on Israeli Jews.