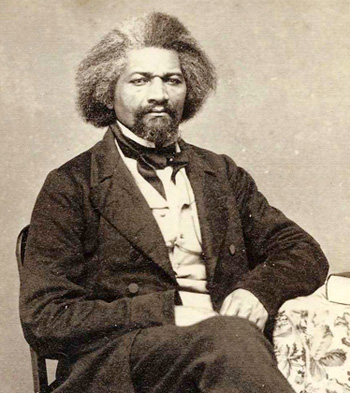

In 1869, amid calls to limit Chinese immigration, Frederick Douglass responded with one of his greatest speeches:

Men, like bees, want elbow room. When the hive is overcrowded, the bees will swarm, and will be likely to take up their abode where they find the best prospect for honey. In matters of this sort, men are very much like bees…. The same mighty forces which have swept to our shores the overflowing populations of Europe; which have reduced the people of Ireland three millions below its normal standard; will operate in a similar manner upon the hungry population of China and other parts of Asia. Home has its charms, and native land has its charms, but hunger, oppression, and destitution, will dissolve these charms and send men in search of new countries and new homes….

Men, like bees, want elbow room. When the hive is overcrowded, the bees will swarm, and will be likely to take up their abode where they find the best prospect for honey. In matters of this sort, men are very much like bees…. The same mighty forces which have swept to our shores the overflowing populations of Europe; which have reduced the people of Ireland three millions below its normal standard; will operate in a similar manner upon the hungry population of China and other parts of Asia. Home has its charms, and native land has its charms, but hunger, oppression, and destitution, will dissolve these charms and send men in search of new countries and new homes….

I have said that the Chinese will come, and have given some reasons why we may expect them in very large numbers in no very distant future. Do you ask, if I favor such immigration, I answer I would….

But are there not reasons against all this? Is there not such a law or principle as that of self-preservation? Does not every race owe something to itself? Should it not attend to the dictates of common sense…? Is there not such a thing as being more generous than wise? In the effort to promote civilization may we not corrupt and destroy what we have? Is it best to take on board more passengers than the ship will carry?

To all of this and more I have one among many answers, altogether satisfactory to me, though I cannot promise that it will be so to you.

I submit that this question of Chinese immigration should be settled upon higher principles than those of a cold and selfish expediency.

There are such things in the world as human rights. They rest upon no conventional foundation, but are external, universal, and indestructible. Among these, is the right of locomotion; the right of migration; the right which belongs to no particular race, but belongs alike to all and to all alike. It is the right you assert by staying here, and your fathers asserted by coming here…. I know of no rights of race superior to the rights of humanity, and when there is a supposed conflict between human and national rights, it is safe to go to the side of humanity. I have great respect for the blue eyed and light haired races of America. They are a mighty people. In any struggle for the good things of this world they need have no fear. They have no need to doubt that they will get their full share.

But I reject the arrogant and scornful theory by which they would limit migratory rights, or any other essential human rights to themselves, and which would make them the owners of this great continent to the exclusion of all other races of men.

I want a home here not only for the negro, the mulatto and the Latin races; but I want the Asiatic to find a home here in the United States, and feel at home here, both for his sake and for ours. Right wrongs no man. If respect is had to majorities, the fact that only one fifth of the population of the globe is white, the other four fifths are colored, ought to have some weight and influence in disposing of this and similar questions. It would be a sad reflection upon the laws of nature and upon the idea of justice, to say nothing of a common Creator, if four fifths of mankind were deprived of the rights of migration to make room for the one fifth….

So much for what is right; now let us see what is wise.

I hold that a liberal and brotherly welcome to all who are likely to come to the United states, is the only wise policy which this nation can adopt….

The apprehension that we shall be swamped or swallowed up by Mongolian civilization… does not seem entitled to much respect. Though they come as the waves come, we shall be stronger if we receive them as friends and give them a reason for loving our country and our institutions. They will find here a deeply rooted, indigenous, growing civilization, augmented by an ever increasing stream of immigration from Europe; and possession is nine points of the law in this case, as well as in others. They will come as strangers, we are at home. They will come to us, not we to them. They will come in their weakness, we shall meet them in our strength. They will come as individuals, we will meet them in multitudes, and with all the advantages of organization. Chinese children are in American schools in San Francisco, none of our children are in Chinese schools, and probably never will be, though in some things they might well teach us valuable lessons. Contact with these yellow children of The Celestial Empire would convince us that the points of human difference, great as they, upon first sight, seem, are as nothing compared with the points of human agreement. Such contact would remove mountains of prejudice….

If it could be shown that any particular race of men are literally incapable of improvement, we might hesitate to welcome them here. But no such men are anywhere to be found, and if there were, it is not likely that they would ever trouble us with their presence. The fact that the Chinese and other nations desire to come and do come, is a proof of their fitness to come….

I close these remarks as I began. If our action shall be in accordance with the principles of justice, liberty, and perfect human equality, no eloquence can adequately portray the greatness and grandeur of the future of the Republic.

We shall spread the network of our science and civilization over all who seek their shelter whether from Asia, Africa, or the Isles of the sea. We shall mold them all, each after his kind, into Americans; Indian and Celt; Negro and Saxon; Latin and Teuton; Mongolian and Caucasian; Jew and Gentile; all shall here bow to the same law, speak the same language, support the same Government, enjoy the same liberty, vibrate with the same national enthusiasm, and seek the same national ends.

Frederick Douglass, 1869.

That was the original idea that drew people to travel as a caravan, and it remains the idea for the people involved. They set off this month because this is the best season to travel through Mexico, after the heat of summer and before the cold and rains of winter.

That was the original idea that drew people to travel as a caravan, and it remains the idea for the people involved. They set off this month because this is the best season to travel through Mexico, after the heat of summer and before the cold and rains of winter. Colonial Exhibition of 1931. The facade of this building, which first housed the Musée des Colonies, is a huge cement bas-relief of scenes from “greater France” — elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers, temples, sailing ships, and toiling or warlike natives of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, set off with mentions of what each area has contributed to the mother country: rice, rubber, cotton, tea…

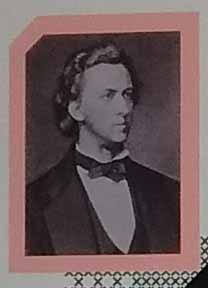

Colonial Exhibition of 1931. The facade of this building, which first housed the Musée des Colonies, is a huge cement bas-relief of scenes from “greater France” — elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers, temples, sailing ships, and toiling or warlike natives of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, set off with mentions of what each area has contributed to the mother country: rice, rubber, cotton, tea… foreigner highlighted on the timeline is Frédéric Chopin, arriving in 1831 “like numerous intellectual, military, political, and artistic Polish insurgents after the failed revolt against the power of the Czar.”

foreigner highlighted on the timeline is Frédéric Chopin, arriving in 1831 “like numerous intellectual, military, political, and artistic Polish insurgents after the failed revolt against the power of the Czar.” This affair notably split French intellectuals and artists, with Degas (a particularly vicious anti-Semite), Renoir, and Cézanne expressing their distaste for the “foreigners” — so denominated though some Jewish families had been in France for many generations — while Monet and Mary Cassatt lined up on the other side, along with Pissarro, who was Jewish, born in the Danish West Indies, and sometimes bore the brunt of his colleagues’ prejudice.

This affair notably split French intellectuals and artists, with Degas (a particularly vicious anti-Semite), Renoir, and Cézanne expressing their distaste for the “foreigners” — so denominated though some Jewish families had been in France for many generations — while Monet and Mary Cassatt lined up on the other side, along with Pissarro, who was Jewish, born in the Danish West Indies, and sometimes bore the brunt of his colleagues’ prejudice.

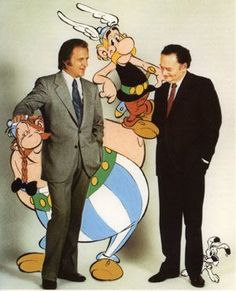

I’m not trying to recap the whole museum — a five-hour visit was not sufficient to explore its range and depth — but a couple more details are worth mentioning. One is the charming irony that the most familiar evocation of an indigenous French heritage, the comic book adventures of Asterix, Obelix, and their fellow Gauls holding out against the Roman Empire, was created by a pair of second-generation immigrants: Alberto Uderzo, whose parents immigrated from Italy shortly before his birth, and René Goscinny, the son of Polish Jews.

I’m not trying to recap the whole museum — a five-hour visit was not sufficient to explore its range and depth — but a couple more details are worth mentioning. One is the charming irony that the most familiar evocation of an indigenous French heritage, the comic book adventures of Asterix, Obelix, and their fellow Gauls holding out against the Roman Empire, was created by a pair of second-generation immigrants: Alberto Uderzo, whose parents immigrated from Italy shortly before his birth, and René Goscinny, the son of Polish Jews. that visitors should be inspired to donate material about their own immigrant families and history in France, among the donations is a baby-foot table (what Americans call foosball and other Anglophones table football) made by the Bonzini family, descendants of Italian immigrants who are one of the main French manufacturers. The Bonzinis originally donated the table for an exhibition called

that visitors should be inspired to donate material about their own immigrant families and history in France, among the donations is a baby-foot table (what Americans call foosball and other Anglophones table football) made by the Bonzini family, descendants of Italian immigrants who are one of the main French manufacturers. The Bonzinis originally donated the table for an exhibition called

“Every time you see a cop on the beat, ask yourself what he is protecting, and from who.”

“Every time you see a cop on the beat, ask yourself what he is protecting, and from who.” And I’m glad all the museums and historical sites use the word “illegal,” because although I understand why some people prefer euphemisms like “undocumented” and “unauthorized,” the reality is that governments make laws to protect some people from other people — and when you argue that the people you support are not criminals, you are arguing that other people can justifiably be labeled that way.

And I’m glad all the museums and historical sites use the word “illegal,” because although I understand why some people prefer euphemisms like “undocumented” and “unauthorized,” the reality is that governments make laws to protect some people from other people — and when you argue that the people you support are not criminals, you are arguing that other people can justifiably be labeled that way. The Israeli contrast –narratives of desperate Jewish refugees throwing cans at soldiers seventy years ago, told to rally support for Jewish soldiers shooting desperate refugees throwing stones today – is particularly striking because the time and space are so compressed. But the essential contrast is so familiar as to be almost universal: virtually all national narratives include brave struggles against oppressive governments, and few governments maintain their power for long with clean hands.

The Israeli contrast –narratives of desperate Jewish refugees throwing cans at soldiers seventy years ago, told to rally support for Jewish soldiers shooting desperate refugees throwing stones today – is particularly striking because the time and space are so compressed. But the essential contrast is so familiar as to be almost universal: virtually all national narratives include brave struggles against oppressive governments, and few governments maintain their power for long with clean hands. As I write, Israeli troops are massed on the no man’s land separating Israel from Gaza, shooting tear gas grenades and live ammunition at Palestinian refugees who are gathered on the other side, throwing rocks, burning tires, and seeking to breech the barriers and send thousands of men, women and children across.

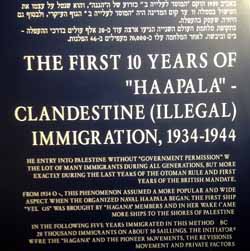

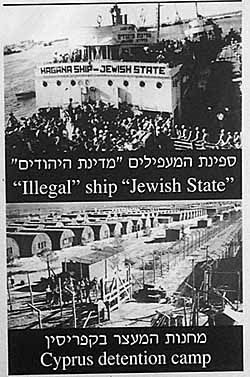

As I write, Israeli troops are massed on the no man’s land separating Israel from Gaza, shooting tear gas grenades and live ammunition at Palestinian refugees who are gathered on the other side, throwing rocks, burning tires, and seeking to breech the barriers and send thousands of men, women and children across. In Tel Aviv, the museum of the Hagganah, the Jewish army that faced British and Arab forces in the late 1940s, has a display honoring “Ha’apala – Clandestine (Illegal) Immigration, 1934-1944,” and two museums of the Etzel, the more radical Jewish underground, likewise celebrate the brave men and women who smuggled Jewish refugees into Palestine, defying the British army and even the Haggana, which in some periods helped the British, much as the Palestinian Authority’s police now work with Israeli forces to control illegal migration from the West Bank.

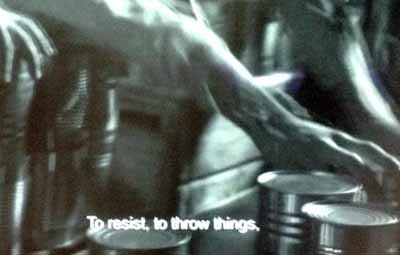

In Tel Aviv, the museum of the Hagganah, the Jewish army that faced British and Arab forces in the late 1940s, has a display honoring “Ha’apala – Clandestine (Illegal) Immigration, 1934-1944,” and two museums of the Etzel, the more radical Jewish underground, likewise celebrate the brave men and women who smuggled Jewish refugees into Palestine, defying the British army and even the Haggana, which in some periods helped the British, much as the Palestinian Authority’s police now work with Israeli forces to control illegal migration from the West Bank. Itzak Belfer, one of the passengers, describes how the British troops were massed on the deck of the destroyer, and someone brought up boxes of tin cans to throw at the soldiers. One of the men commanding the ship for the Palyam, the Jewish rebel navy, recalls: “We told them to give the British a hard time — to resist, to throw things, not let them board the ship, and maybe we could make it to the shore.”

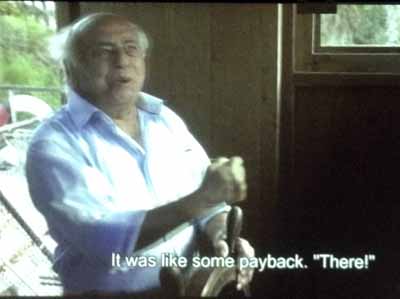

Itzak Belfer, one of the passengers, describes how the British troops were massed on the deck of the destroyer, and someone brought up boxes of tin cans to throw at the soldiers. One of the men commanding the ship for the Palyam, the Jewish rebel navy, recalls: “We told them to give the British a hard time — to resist, to throw things, not let them board the ship, and maybe we could make it to the shore.” The British soldiers began to board, and Belfer, his voice thrilling at the memory, recalls throwing the cans of food at them: “That kind of can, when someone throws it, it can do a lot of damage.” Then the Palyam man on the ship’s bridge angrily turned the wheel and rammed their boat into the destroyer. “We were all knocked down,” Belfer says, but “We all felt like… ‘We did it! We showed them!’”

The British soldiers began to board, and Belfer, his voice thrilling at the memory, recalls throwing the cans of food at them: “That kind of can, when someone throws it, it can do a lot of damage.” Then the Palyam man on the ship’s bridge angrily turned the wheel and rammed their boat into the destroyer. “We were all knocked down,” Belfer says, but “We all felt like… ‘We did it! We showed them!’”