In a conscious display of historical irony, France has established its Cité Nationale de l’Histoire de l’Immigration in the Palais de la Porte Dorée, an astonishing building constructed for the International  Colonial Exhibition of 1931. The facade of this building, which first housed the Musée des Colonies, is a huge cement bas-relief of scenes from “greater France” — elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers, temples, sailing ships, and toiling or warlike natives of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, set off with mentions of what each area has contributed to the mother country: rice, rubber, cotton, tea…

Colonial Exhibition of 1931. The facade of this building, which first housed the Musée des Colonies, is a huge cement bas-relief of scenes from “greater France” — elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers, temples, sailing ships, and toiling or warlike natives of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, set off with mentions of what each area has contributed to the mother country: rice, rubber, cotton, tea…

Within, huge frescoes continue the theme, but the timeline leading up the stairs tells a different story: how France itself has been a center of immigration for centuries, and how its laws and narratives have shifted over the years, sometimes embracing outsiders, sometimes trying to shut them out, and sometimes changing the notion of who is or isn’t an outsider.

This is particularly significant because France — la belle France, cradle of liberty and wonderful cheeses — is so often mentioned by xenophobes as an example of the nation-state ideal, a place with a homogeneous population that lived happily together until the recent onslaught of brown-skinned foreigners, who now threaten the brave traditions of secularism, feminism, enlightenment ideals, and cheese-making.

The museum’s timeline starts in 1789, when the French revolutionaries declared the equality of all citizens — and simultaneously established the differentiation of French citizens from foreigners. Previously, such a differentiation had not mattered, since peasants were peasants, whatever their place of birth. Now, rather than lords and peasants, we had citizens and non-citizens… and the first  foreigner highlighted on the timeline is Frédéric Chopin, arriving in 1831 “like numerous intellectual, military, political, and artistic Polish insurgents after the failed revolt against the power of the Czar.”

foreigner highlighted on the timeline is Frédéric Chopin, arriving in 1831 “like numerous intellectual, military, political, and artistic Polish insurgents after the failed revolt against the power of the Czar.”

Before the 20th century there was no attempt to control entry to France, but through the 19th century there was increased interest in tabulating and identifying foreign residents. The first census to count foreigners, in 1851, found a third of a million, which by 1881 had grown to a million, making up 3% of the population. The country had to address a new question: when does a foreigner cease to be foreign? In 1889 France came up with one answer, establishing automatic citizenship for third-generation immigrants — people born in France to parents who were also born in France.

At that point most of the country’s foreign residents were European, but that didn’t mean they were easily assimilated. There were deadly clashes between French workers and Italian immigrants, sometimes mounting to chasses aux Italiens (Italian hunts) in which immigrants were beaten and killed. There was also the Dreyfus affair, in which an army captain from a French Jewish family was convicted of treason on the basis of forged evidence and sent to Devil’s Island, in French Guiana.  This affair notably split French intellectuals and artists, with Degas (a particularly vicious anti-Semite), Renoir, and Cézanne expressing their distaste for the “foreigners” — so denominated though some Jewish families had been in France for many generations — while Monet and Mary Cassatt lined up on the other side, along with Pissarro, who was Jewish, born in the Danish West Indies, and sometimes bore the brunt of his colleagues’ prejudice.1 (The museum timeline doesn’t go into the Impressionists’ opinions, but does include later letters requesting French citizenship from Picasso and Apollinaire — I had not known that the latter was originally an Italian-born Pole named Wilhelm Kostrowicki.)

This affair notably split French intellectuals and artists, with Degas (a particularly vicious anti-Semite), Renoir, and Cézanne expressing their distaste for the “foreigners” — so denominated though some Jewish families had been in France for many generations — while Monet and Mary Cassatt lined up on the other side, along with Pissarro, who was Jewish, born in the Danish West Indies, and sometimes bore the brunt of his colleagues’ prejudice.1 (The museum timeline doesn’t go into the Impressionists’ opinions, but does include later letters requesting French citizenship from Picasso and Apollinaire — I had not known that the latter was originally an Italian-born Pole named Wilhelm Kostrowicki.)

The timeline moves on through World War I, when France recruited hundreds of thousands of foreign workers from allied countries and its various colonies, and established the first national identity cards to keep track of them. By 1931 France had overtaken the United States as the country with the most foreign residents: 2.7 million, representing about 7% of the population. Then came the Depression, and with it a flood of new laws limiting the rights of non-native workers, as well as attempts to send them back to their countries of origin. In World War II foreigners came briefly back in fashion — 178,000 African-French subjects (not to be confused with citizens) were recruited to fight for the motherland — and 15,000 French citizens were stripped of their citizenship. (Many were Communists or people who had left the country, but 40% were Jews, including Marc Chagall, characterized as “a painter of no national interest,” and the young Serge Gainsbourg — and that doesn’t include the 110,000 French-Algerian Jews who likewise ceased to be officially French, among them Jacques Derrida.)

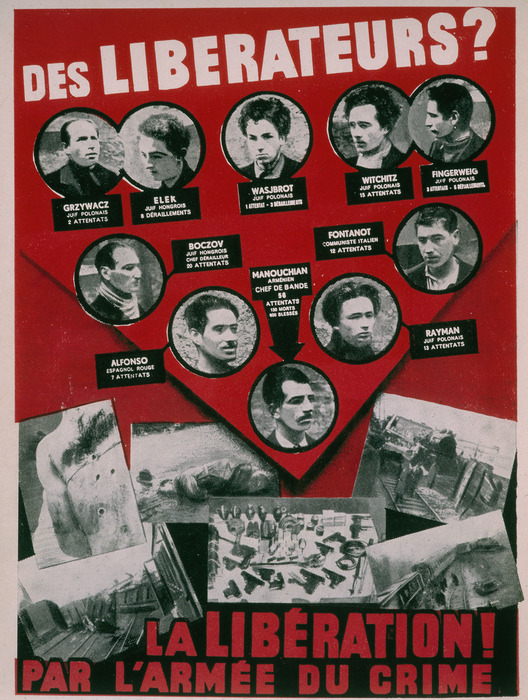

In the upstairs galleries, a poster known as l’affiche rouge gives a sense of how the Vichy government used the fantasy of a pure French heritage to discredit its opponents. The poster sneers at fighters remembered in hindsight as members the valiant French resistance, setting off the foreign names of recently executed fighters with the notations “Polish Jew,” “Italian Communist,” and “Spanish Red.” It warns:

If the French pillage, steal, commit sabotage, and kill… It is always foreigners who command them. It is always the unemployed and professional criminals who carry out the orders. It is always the Jews who inspire them…. This gangsterism is not an expression of wounded Patriotism, it is a foreign plot against the lives of the French and against the sovereignty of France.

One question the museum tackles less thoroughly is the overlap between colonization and immigration. It tends to characterize these as separate, though overlapping, issues, but throughout treats France as a European territory in which non-Europeans are by definition immigrants — which ignores the French citizens of Algeria, when it was part of France, and of the current French departments of Martinique, Guadeloupe, Guyane, La Réunion, and Mayotte. For example, when noting that in 1975 France had 3.4 million foreign residents, the largest groups being Portuguese and Algerians, it does not mention that some of the Algerian foreigners may have previously been French — though it does note that in 1993 the loi Mehaignerie modified the automatic assumption of French citizenship for French-born children of people born in France in cases where the parents were born in regions that were no longer part of France… presumably to deal with a potential surplus of dark-skinned heirs to nos ancêtres les Gaulois.2

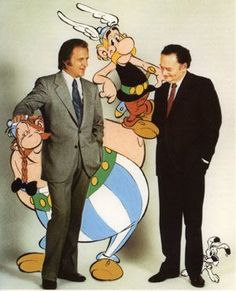

I’m not trying to recap the whole museum — a five-hour visit was not sufficient to explore its range and depth — but a couple more details are worth mentioning. One is the charming irony that the most familiar evocation of an indigenous French heritage, the comic book adventures of Asterix, Obelix, and their fellow Gauls holding out against the Roman Empire, was created by a pair of second-generation immigrants: Alberto Uderzo, whose parents immigrated from Italy shortly before his birth, and René Goscinny, the son of Polish Jews.

I’m not trying to recap the whole museum — a five-hour visit was not sufficient to explore its range and depth — but a couple more details are worth mentioning. One is the charming irony that the most familiar evocation of an indigenous French heritage, the comic book adventures of Asterix, Obelix, and their fellow Gauls holding out against the Roman Empire, was created by a pair of second-generation immigrants: Alberto Uderzo, whose parents immigrated from Italy shortly before his birth, and René Goscinny, the son of Polish Jews.

The other detail requires a little background: In October 2010, a group of roughly 500 undocumented workers, mostly from Sub-Saharan Africa, occupied the museum demanding regularization of their residence in France, and remained through January 2011. I have not sorted out the details of that story, but noted a nice footnote in the section of the museum dedicated to donations. The idea of this section is  that visitors should be inspired to donate material about their own immigrant families and history in France, among the donations is a baby-foot table (what Americans call foosball and other Anglophones table football) made by the Bonzini family, descendants of Italian immigrants who are one of the main French manufacturers. The Bonzinis originally donated the table for an exhibition called Allez la France! Football et immigration, histoires croisées (Go France! Soccer and immigration, intertwining histories), which was to be followed by an exhibit at Le Musée National du Sport called Allez la France! Les footballeurs africains sont là! (Go France! The African footballers have arrived!). Since the point of these exhibits was the French team’s African-born or African-descended stars, the Bronzinis took the high road and reacted to the occupation of the museum by donating another ten tables to help the occupiers occupy their time.

that visitors should be inspired to donate material about their own immigrant families and history in France, among the donations is a baby-foot table (what Americans call foosball and other Anglophones table football) made by the Bonzini family, descendants of Italian immigrants who are one of the main French manufacturers. The Bonzinis originally donated the table for an exhibition called Allez la France! Football et immigration, histoires croisées (Go France! Soccer and immigration, intertwining histories), which was to be followed by an exhibit at Le Musée National du Sport called Allez la France! Les footballeurs africains sont là! (Go France! The African footballers have arrived!). Since the point of these exhibits was the French team’s African-born or African-descended stars, the Bronzinis took the high road and reacted to the occupation of the museum by donating another ten tables to help the occupiers occupy their time.

So… altogether an interesting visit, and much to think about.

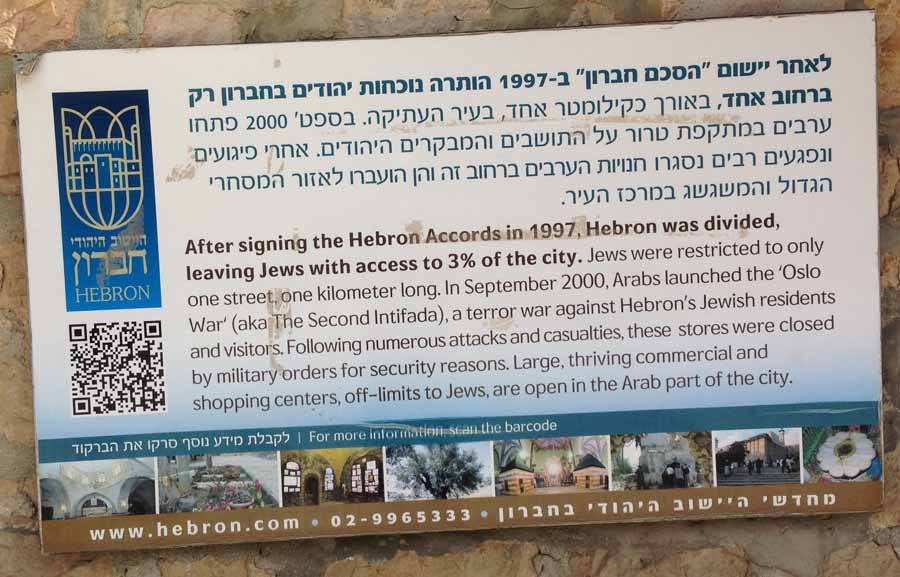

I put the word “Jews” in quotation marks because in this instance I’m quoting a particular sign I photographed, which describes the city’s “large, thriving commercial and shopping centers, off-limits to Jews…” The stress on “large” and “thriving” underlines the point that, although 3% of Hebron’s physical area — the urban center of the southern West Bank — is off-limits to the city’s 200,000 Palestinian residents (both Muslim and Christian), with checkpoints manned by soldiers to enforce that prohibition, the remaining 97% of the city is open to Palestinians and off-limits to Jews…

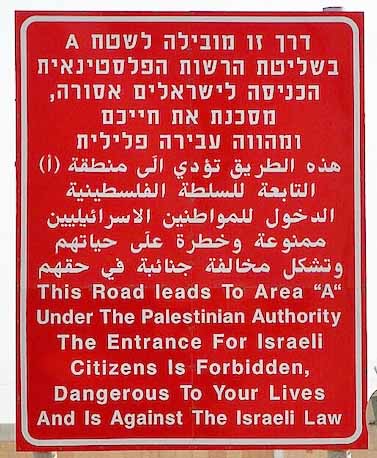

I put the word “Jews” in quotation marks because in this instance I’m quoting a particular sign I photographed, which describes the city’s “large, thriving commercial and shopping centers, off-limits to Jews…” The stress on “large” and “thriving” underlines the point that, although 3% of Hebron’s physical area — the urban center of the southern West Bank — is off-limits to the city’s 200,000 Palestinian residents (both Muslim and Christian), with checkpoints manned by soldiers to enforce that prohibition, the remaining 97% of the city is open to Palestinians and off-limits to Jews… divisions: the West Bank is often described as Palestinian territory, but only the urban areas, comprising a bit less than 20% of the total land, are under direct Palestinian control. Those are the scattered pockets classified as Area A, which Israelis are forbidden to enter (except soldiers, who enter them daily to conduct raids and arrests). Area B, accounting for another 20% of the West Bank, includes smaller Palestinian towns and villages, and is under Palestinian civil control with joint Palestinian/Israeli police/military control, and likewise barred to Israelis. The remaining 60% (actually, a bit more) is under full Israeli civil and military control; this includes the settlements, virtually all the unsettled countryside, and most of the main roads, all of which are open to Israelis – hence the signs at highway exits leading to any Palestinian city, town, or village warning Israeli drivers it is dangerous and illegal to go there.

divisions: the West Bank is often described as Palestinian territory, but only the urban areas, comprising a bit less than 20% of the total land, are under direct Palestinian control. Those are the scattered pockets classified as Area A, which Israelis are forbidden to enter (except soldiers, who enter them daily to conduct raids and arrests). Area B, accounting for another 20% of the West Bank, includes smaller Palestinian towns and villages, and is under Palestinian civil control with joint Palestinian/Israeli police/military control, and likewise barred to Israelis. The remaining 60% (actually, a bit more) is under full Israeli civil and military control; this includes the settlements, virtually all the unsettled countryside, and most of the main roads, all of which are open to Israelis – hence the signs at highway exits leading to any Palestinian city, town, or village warning Israeli drivers it is dangerous and illegal to go there.