I spent my second day in Hebron walking around, taking pictures, getting a better sense of where everything was. I went through a couple of full-scale checkpoints with turnstiles and metal detectors, and others with just a couple of soldiers with automatic rifles, and wherever I went they waved me through with a smile, even when I set off the metal detectors — I was asked my nationality a couple of times and once asked for my passport, but just to see I had one, not to open it and check my photo… because I was obviously a tourist and everybody wants more of those.

I spent my second day in Hebron walking around, taking pictures, getting a better sense of where everything was. I went through a couple of full-scale checkpoints with turnstiles and metal detectors, and others with just a couple of soldiers with automatic rifles, and wherever I went they waved me through with a smile, even when I set off the metal detectors — I was asked my nationality a couple of times and once asked for my passport, but just to see I had one, not to open it and check my photo… because I was obviously a tourist and everybody wants more of those.

So, as I say, I was wandering all over, getting lost, retracing the same streets multiple times, exploring the old city, the Jewish settler area,  the hills above… it’s weird and fascinating, because these inimical populations are completely intertwined, sometimes on different floors of the same house. And no one was bothering me — some people didn’t return my hellos, but the soldiers were consistently polite and cheerful, and when I asked if I could take their picture they said, “Sure, you can do anything you want…”

the hills above… it’s weird and fascinating, because these inimical populations are completely intertwined, sometimes on different floors of the same house. And no one was bothering me — some people didn’t return my hellos, but the soldiers were consistently polite and cheerful, and when I asked if I could take their picture they said, “Sure, you can do anything you want…”

So then I was up on the hillside above the old city and noticed, walking ahead of me, a couple of white-haired women whom a life in Cambridge, Massachusetts, had equipped me to instantly recognize as committed social activists — in another context I would have asked if they knew my mom. So I went over, said hello, and asked if they could help me understand what I was looking at. They turned out to be Israelis from a group called Machsom Watch (Checkpoint Watch) who had been coming to Hebron a few times a year for 15 years, acting as observers and writing reports on how the situation was changing.

They were very helpful, telling me how things were different in various periods, and we gradually made our way down the hill and back to the street in front of the Ibrahimi Mosque, which I had already walked up and down at least three times. They introduced me to a Palestinian man who runs a souvenir shop there, and while we were chatting the Israeli soldiers who were guarding that end of the street came over from the checkpoint and asked the women who they were and what they were doing. Then the women left to catch their ride back to Tel Aviv, and I had a coffee in the souvenir shop and headed back towards that street in front of the mosque, which was also the street to the hostel where I was staying…

They were very helpful, telling me how things were different in various periods, and we gradually made our way down the hill and back to the street in front of the Ibrahimi Mosque, which I had already walked up and down at least three times. They introduced me to a Palestinian man who runs a souvenir shop there, and while we were chatting the Israeli soldiers who were guarding that end of the street came over from the checkpoint and asked the women who they were and what they were doing. Then the women left to catch their ride back to Tel Aviv, and I had a coffee in the souvenir shop and headed back towards that street in front of the mosque, which was also the street to the hostel where I was staying…

…but this time, the soldiers didn’t just wave me past. They asked where I was from, and took my passport, and told me to stand back while they first examined the identification of a young Muslim woman and asked her a lot of questions. Then they waved her past and asked if I was with those two women  they’d seen me with. I said no, and they asked where I was going. I said I was going back to my hostel. They asked, “You are a Jew?” I said yes. They said, “You cannot go here.”

they’d seen me with. I said no, and they asked where I was going. I said I was going back to my hostel. They asked, “You are a Jew?” I said yes. They said, “You cannot go here.”

Now, the division of Hebron is complicated even by Israeli/Palestinian standards: the soldiers are very clearly protecting the Israeli settlers from the Palestinian locals, but the current separation followed the killing of 29 Muslims by a Jewish/American/Israeli settler in that very mosque 24 years ago, and since then the mosque part of the building has been kept separate from a smaller section that functions as a synagogue — which is what it was back in Herod’s day, and it has also been a Christian Church, and basically it’s holy to everybody and is the city’s main tourist attraction and I’d already visited it earlier that morning… but for religious purposes, it is firmly divided into Muslim and Jewish sections, with separate entrances on opposite sides to prevent any possible clashes. So OK, there was a logical reason to prevent me, as a Jew, from entering the Muslim side… but, as I say, I’d already walked back and forth down this same street several times, passing this same checkpoint, and had already visited the mosque, and no one had shown the slightest interest in my religious or ethnic identity.

So I explained that I wasn’t going to the mosque, and anyway was not religiously Jewish, and had been wandering back and forth through this same checkpoint for two days, and was just going to my hostel. One of them called their superior on their field phone, chatted briefly, then came back and said, “You are a Jew, you can’t go here.”

I said, “Suppose I say I’m just an American tourist, and not a Jew?”

By now the taller soldier was getting annoyed. Leaning forward, he aggressively snapped: “Are you a Jew?!”

I said, “My great-grandparents were Jewish, but I’ve never been religious… so if I say I’m not Jewish can I go through?”

He called again to ask his superior, then said, “If you are Muslim or Christian, you can go here, but Jews have to go there…” gesturing to the other entrance.

I said, “But I’m not going in this building at all, I’m just walking back down the street to the old city.”

He said, louder than ever, “Are you a Jew? If you are a Jew you can’t go here.”

The conversation was obviously not going to change, I had no particular reason to go back the same way I’d come, and I was not accomplishing anything by continuing to argue. So I decided to explore the alternatives: “OK, how else can I get back to the old city?” The taller soldier gestured that I could go around through the Jewish area, or around the back of the mosque.

I walked up the dirt road that led behind the mosque, into a thoroughly Arab neighborhood, wandered up dirt roads and down alleys, asked a couple of people for directions, and eventually wound my way down to the other end of the same street in front of the mosque… where another pair of soldiers who hadn’t seen me consorting with elderly Israeli peace observers waved me through with a smile. So that was that. I walked back through the market, bought a handful of almonds and a falafel sandwich with roast eggplant, hot pepper sauce, and pickled vegetables, retrieved my guitar and pack from the hostel, and caught a minibus to Bethlehem.

I walked up the dirt road that led behind the mosque, into a thoroughly Arab neighborhood, wandered up dirt roads and down alleys, asked a couple of people for directions, and eventually wound my way down to the other end of the same street in front of the mosque… where another pair of soldiers who hadn’t seen me consorting with elderly Israeli peace observers waved me through with a smile. So that was that. I walked back through the market, bought a handful of almonds and a falafel sandwich with roast eggplant, hot pepper sauce, and pickled vegetables, retrieved my guitar and pack from the hostel, and caught a minibus to Bethlehem.

Make of it what you will.

I didn’t understand that until I spent a month traveling in Israel and the West Bank. I had heard about the wall there, both from supporters of the Israeli government who credit it with ending terrorist bombings and from supporters of the Palestinians who see it as an instrument for grabbing Palestinian land, dividing Palestinian farmers from their fields, making life difficult for Palestinians who need to cross into Israel, and reminding Palestinians that they are trapped and isolated.

I didn’t understand that until I spent a month traveling in Israel and the West Bank. I had heard about the wall there, both from supporters of the Israeli government who credit it with ending terrorist bombings and from supporters of the Palestinians who see it as an instrument for grabbing Palestinian land, dividing Palestinian farmers from their fields, making life difficult for Palestinians who need to cross into Israel, and reminding Palestinians that they are trapped and isolated.

and motion sensors. Given all the stories of Palestinian climbers, I would not be surprised if these less imposing stretches are actually a more effective barrier—but the towering concrete wall is far more impressive, and it struck me that its massive ugliness is no accident. Its size and weight are a constant reminder to Israeli Jews of the horrors lurking on the other side, the enemies so fearsome that mere wire cannot keep them out. It is theater; theater of fear.

and motion sensors. Given all the stories of Palestinian climbers, I would not be surprised if these less imposing stretches are actually a more effective barrier—but the towering concrete wall is far more impressive, and it struck me that its massive ugliness is no accident. Its size and weight are a constant reminder to Israeli Jews of the horrors lurking on the other side, the enemies so fearsome that mere wire cannot keep them out. It is theater; theater of fear. and what better way to divide than with a towering wall?

and what better way to divide than with a towering wall?

nk, in Jordan, in refugee camps, and in a global diaspora. Some have famously kept the keys to the houses they or their grandparents left – the key has become a symbol of Palestinian return; some tell stories of visiting Haifa in later years, knocking on the doors of their houses and asking the Jewish owners if they could walk through the rooms, see if their family pictures were still on the walls, their rugs still on the floors; others have never set foot in Israel and talk longingly of visiting the places they heard of from their parents or grand-parents.

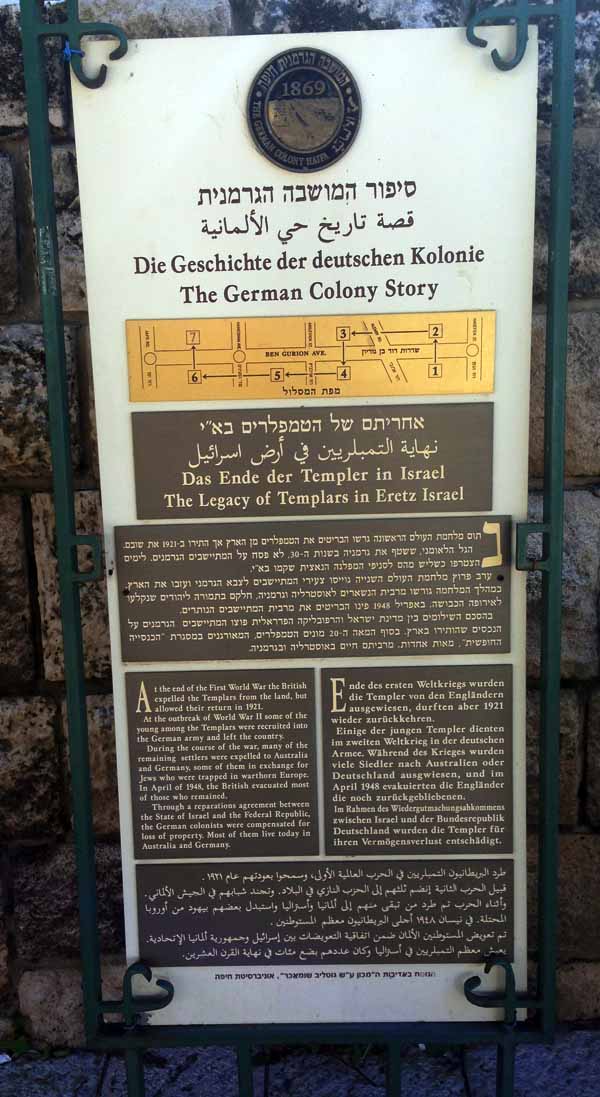

nk, in Jordan, in refugee camps, and in a global diaspora. Some have famously kept the keys to the houses they or their grandparents left – the key has become a symbol of Palestinian return; some tell stories of visiting Haifa in later years, knocking on the doors of their houses and asking the Jewish owners if they could walk through the rooms, see if their family pictures were still on the walls, their rugs still on the floors; others have never set foot in Israel and talk longingly of visiting the places they heard of from their parents or grand-parents. Which is why I was startled by an informational sign on Ben Gurion Avenue in Haifa telling “Die Geschichte der deutschen Kolonie/The German Colony Story,” and in particular about the Templars, a German Protestant group that settled there in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Which is why I was startled by an informational sign on Ben Gurion Avenue in Haifa telling “Die Geschichte der deutschen Kolonie/The German Colony Story,” and in particular about the Templars, a German Protestant group that settled there in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Karl Ruff, an architect born to Templar parents in Haifa in 1904, made contact with the German Nazis in 1931, two years before Hitler came to power, and helped form a core of support that grew into a full-blown Palestinian branch by 1933. A year later, Ludwig Buchhalter, a teacher at the Templar school in Jerusalem, was active in getting the German consul removed from office for having a Jewish wife, arguing “a person who has relations with Jewish circles cannot be loyal to German interests…”

Karl Ruff, an architect born to Templar parents in Haifa in 1904, made contact with the German Nazis in 1931, two years before Hitler came to power, and helped form a core of support that grew into a full-blown Palestinian branch by 1933. A year later, Ludwig Buchhalter, a teacher at the Templar school in Jerusalem, was active in getting the German consul removed from office for having a Jewish wife, arguing “a person who has relations with Jewish circles cannot be loyal to German interests…” The Templar colony of Sarona, established in 1871 just north of the Arab city of Jaffa, preceded the first Jewish settlement in what is now Tel Aviv and pioneered the export of Jaffa oranges. Now a thriving, upscale neighborhood, Sarona has a museum tracing the history of the German settlement, which includes a room devoted to the Nazi period, but also photos and memorabilia of the early German colonists, their lovely houses, and their fertile farms.

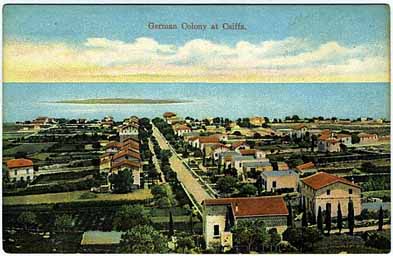

The Templar colony of Sarona, established in 1871 just north of the Arab city of Jaffa, preceded the first Jewish settlement in what is now Tel Aviv and pioneered the export of Jaffa oranges. Now a thriving, upscale neighborhood, Sarona has a museum tracing the history of the German settlement, which includes a room devoted to the Nazi period, but also photos and memorabilia of the early German colonists, their lovely houses, and their fertile farms. In the middle of a sparsely populated and largely barren land, laboring under deficient rule, hundreds of German settlers characterized by great energy, resourcefulness, religious fervor and a variety of professional backgrounds, established a garden city unlike any that existed in the country until then. Outside the Haifa city walls, a boulevard sprang up stretching from the foot of the hills to the sea. It was lined with gardens and homes, remarkable for their beauty.

In the middle of a sparsely populated and largely barren land, laboring under deficient rule, hundreds of German settlers characterized by great energy, resourcefulness, religious fervor and a variety of professional backgrounds, established a garden city unlike any that existed in the country until then. Outside the Haifa city walls, a boulevard sprang up stretching from the foot of the hills to the sea. It was lined with gardens and homes, remarkable for their beauty. Israel and Germany are now allies, Haifa is celebrated as a model of multicultural coexistence, and those markers in the heart of the old port provide a nice history to match its current image: once largely barren and sparsely populated, Haifa was settled by industrious Germans who founded a unique garden city, planted vineyards and olive groves, created new industries, and built a power station and a regional transport system. In 1902 Theodor Herzl’s utopian novel, Altneuland, envisioned this European outpost as the economic center of a future land of Israel, and it soon became a magnet for Jewish settlement. Eventually global politics forced the Germans to leave, but they were paid proper compensation and Haifa today is a lovely, cosmopolitan center, a perfect blend of European civilization and Middle Eastern charm. The Arab population remains relatively sparse numerically, but continues to thrive, a vibrant community with popular nightclubs, restaurants, and a rich arts scene.

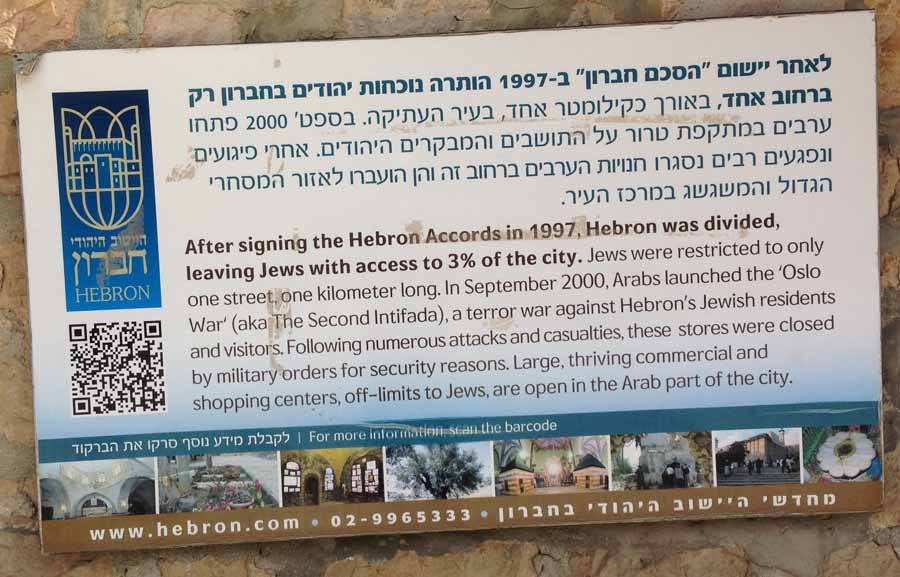

Israel and Germany are now allies, Haifa is celebrated as a model of multicultural coexistence, and those markers in the heart of the old port provide a nice history to match its current image: once largely barren and sparsely populated, Haifa was settled by industrious Germans who founded a unique garden city, planted vineyards and olive groves, created new industries, and built a power station and a regional transport system. In 1902 Theodor Herzl’s utopian novel, Altneuland, envisioned this European outpost as the economic center of a future land of Israel, and it soon became a magnet for Jewish settlement. Eventually global politics forced the Germans to leave, but they were paid proper compensation and Haifa today is a lovely, cosmopolitan center, a perfect blend of European civilization and Middle Eastern charm. The Arab population remains relatively sparse numerically, but continues to thrive, a vibrant community with popular nightclubs, restaurants, and a rich arts scene. I put the word “Jews” in quotation marks because in this instance I’m quoting a particular sign I photographed, which describes the city’s “large, thriving commercial and shopping centers, off-limits to Jews…” The stress on “large” and “thriving” underlines the point that, although 3% of Hebron’s physical area — the urban center of the southern West Bank — is off-limits to the city’s 200,000 Palestinian residents (both Muslim and Christian), with checkpoints manned by soldiers to enforce that prohibition, the remaining 97% of the city is open to Palestinians and off-limits to Jews…

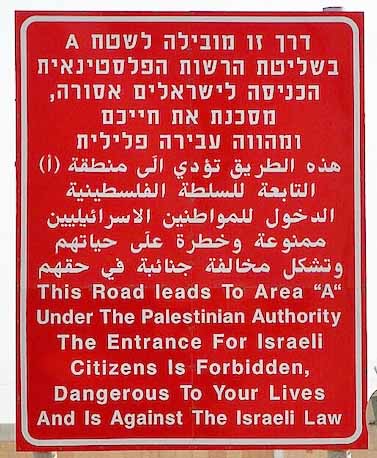

I put the word “Jews” in quotation marks because in this instance I’m quoting a particular sign I photographed, which describes the city’s “large, thriving commercial and shopping centers, off-limits to Jews…” The stress on “large” and “thriving” underlines the point that, although 3% of Hebron’s physical area — the urban center of the southern West Bank — is off-limits to the city’s 200,000 Palestinian residents (both Muslim and Christian), with checkpoints manned by soldiers to enforce that prohibition, the remaining 97% of the city is open to Palestinians and off-limits to Jews… divisions: the West Bank is often described as Palestinian territory, but only the urban areas, comprising a bit less than 20% of the total land, are under direct Palestinian control. Those are the scattered pockets classified as Area A, which Israelis are forbidden to enter (except soldiers, who enter them daily to conduct raids and arrests). Area B, accounting for another 20% of the West Bank, includes smaller Palestinian towns and villages, and is under Palestinian civil control with joint Palestinian/Israeli police/military control, and likewise barred to Israelis. The remaining 60% (actually, a bit more) is under full Israeli civil and military control; this includes the settlements, virtually all the unsettled countryside, and most of the main roads, all of which are open to Israelis – hence the signs at highway exits leading to any Palestinian city, town, or village warning Israeli drivers it is dangerous and illegal to go there.

divisions: the West Bank is often described as Palestinian territory, but only the urban areas, comprising a bit less than 20% of the total land, are under direct Palestinian control. Those are the scattered pockets classified as Area A, which Israelis are forbidden to enter (except soldiers, who enter them daily to conduct raids and arrests). Area B, accounting for another 20% of the West Bank, includes smaller Palestinian towns and villages, and is under Palestinian civil control with joint Palestinian/Israeli police/military control, and likewise barred to Israelis. The remaining 60% (actually, a bit more) is under full Israeli civil and military control; this includes the settlements, virtually all the unsettled countryside, and most of the main roads, all of which are open to Israelis – hence the signs at highway exits leading to any Palestinian city, town, or village warning Israeli drivers it is dangerous and illegal to go there. When I mentioned to friends in the United States that I was headed there, many warned me to be careful — the West Bank is only mentioned in the US media when there is violence, so we associate it with violence. When I mentioned my plans to Jewish Israelis, the reactions were more varied: some were concerned about my safety, some puzzled why I wanted to go, some curious to hear what it is like, some irritated that I would expect to learn something about the region on a short visit — with the assumption I would come away more critical of Israeli policies — some encouraging me and saying they wished they could go there as well.

When I mentioned to friends in the United States that I was headed there, many warned me to be careful — the West Bank is only mentioned in the US media when there is violence, so we associate it with violence. When I mentioned my plans to Jewish Israelis, the reactions were more varied: some were concerned about my safety, some puzzled why I wanted to go, some curious to hear what it is like, some irritated that I would expect to learn something about the region on a short visit — with the assumption I would come away more critical of Israeli policies — some encouraging me and saying they wished they could go there as well. seeing someplace new, having a vacation. The Lonely Planet guidebook to Israel and the Palestinian Territories begins the relevant section on cheerful note:

seeing someplace new, having a vacation. The Lonely Planet guidebook to Israel and the Palestinian Territories begins the relevant section on cheerful note: I recommend any traveler visiting Israel spend some time on the West Bank — not just a day-trip to Bethlehem, but staying a while, going to nightclubs in Ramallah, exploring the old city of Nablus, visiting the Freedom Theater in Jenin, or hiking around the Jordan Valley — and be assured, there are plenty of other travelers making those trips (women as well as men, often on their own), and having a wonderful time.

I recommend any traveler visiting Israel spend some time on the West Bank — not just a day-trip to Bethlehem, but staying a while, going to nightclubs in Ramallah, exploring the old city of Nablus, visiting the Freedom Theater in Jenin, or hiking around the Jordan Valley — and be assured, there are plenty of other travelers making those trips (women as well as men, often on their own), and having a wonderful time. My first night in Ramallah, I got in a long discussion with Nidal Abu Maria, who owns

My first night in Ramallah, I got in a long discussion with Nidal Abu Maria, who owns  That choice is notable because France is not “normal” in the sense of being typical; on the contrary, it has long been held up as an ideal, particularly for German-speaking Central Europeans who dreamed of living wie Gott in Frankreich (like God in France), and more particularly for Central European Jews: Joseph Roth, arriving in France via Vienna and Berlin in the interwar years, wrote, “Paris is where the Eastern Jew begins to become a Western European.”

That choice is notable because France is not “normal” in the sense of being typical; on the contrary, it has long been held up as an ideal, particularly for German-speaking Central Europeans who dreamed of living wie Gott in Frankreich (like God in France), and more particularly for Central European Jews: Joseph Roth, arriving in France via Vienna and Berlin in the interwar years, wrote, “Paris is where the Eastern Jew begins to become a Western European.” solution, a one-state solution, or even a nasty war — but, in any case, resolved. A lot of conversations in Israel reinforce that impression, but after a while I realized that if I didn’t steer the talk in that direction it needn’t go there and most Israelis could probably go for days without mentioning the Occupied Territories or any Palestinian conflict. Because, quite simply, it doesn’t affect their day-to-day life. Yes, they see soldiers all around, often carrying automatic rifles, but being in the army is a basic part of growing up for most Israelis, so they’re used to that. And it is easy to live within a few minutes walk of the wall that blocks off the West Bank and never see it, or ever talk to a Palestinian — or to talk to Palestinians, but not about that.

solution, a one-state solution, or even a nasty war — but, in any case, resolved. A lot of conversations in Israel reinforce that impression, but after a while I realized that if I didn’t steer the talk in that direction it needn’t go there and most Israelis could probably go for days without mentioning the Occupied Territories or any Palestinian conflict. Because, quite simply, it doesn’t affect their day-to-day life. Yes, they see soldiers all around, often carrying automatic rifles, but being in the army is a basic part of growing up for most Israelis, so they’re used to that. And it is easy to live within a few minutes walk of the wall that blocks off the West Bank and never see it, or ever talk to a Palestinian — or to talk to Palestinians, but not about that. but if you frame them as ways to reduce tension and let off steam while extending the wall, maintaining the checkpoints, expanding the settlements, ensuring the refugees in Lebanon and Jordan do not return, and carrying out daily raids, arrests, and frequently killings on the West Bank — that is, while keeping things the way they are — they feel not like progress but like ways of normalizing the status quo.

but if you frame them as ways to reduce tension and let off steam while extending the wall, maintaining the checkpoints, expanding the settlements, ensuring the refugees in Lebanon and Jordan do not return, and carrying out daily raids, arrests, and frequently killings on the West Bank — that is, while keeping things the way they are — they feel not like progress but like ways of normalizing the status quo. …and I’m not just making an analogy: Israeli companies are exporting their well-tested technology around the world, so, for example, Elbit Systems has provided Arizona with the same electronic detection fence system used to separate Israelis from Palestinians and now boasts on its website that “recent… activities in the homeland security area include initiation of the first phase of the Integrated Fixed Towers program for the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Agency and the award of contracts for homeland security solutions for Latin American customers.”

…and I’m not just making an analogy: Israeli companies are exporting their well-tested technology around the world, so, for example, Elbit Systems has provided Arizona with the same electronic detection fence system used to separate Israelis from Palestinians and now boasts on its website that “recent… activities in the homeland security area include initiation of the first phase of the Integrated Fixed Towers program for the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Agency and the award of contracts for homeland security solutions for Latin American customers.” “Every time you see a cop on the beat, ask yourself what he is protecting, and from who.”

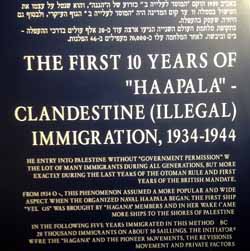

“Every time you see a cop on the beat, ask yourself what he is protecting, and from who.” And I’m glad all the museums and historical sites use the word “illegal,” because although I understand why some people prefer euphemisms like “undocumented” and “unauthorized,” the reality is that governments make laws to protect some people from other people — and when you argue that the people you support are not criminals, you are arguing that other people can justifiably be labeled that way.

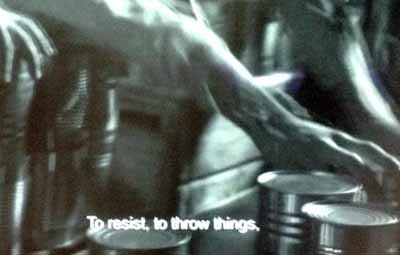

And I’m glad all the museums and historical sites use the word “illegal,” because although I understand why some people prefer euphemisms like “undocumented” and “unauthorized,” the reality is that governments make laws to protect some people from other people — and when you argue that the people you support are not criminals, you are arguing that other people can justifiably be labeled that way. The Israeli contrast –narratives of desperate Jewish refugees throwing cans at soldiers seventy years ago, told to rally support for Jewish soldiers shooting desperate refugees throwing stones today – is particularly striking because the time and space are so compressed. But the essential contrast is so familiar as to be almost universal: virtually all national narratives include brave struggles against oppressive governments, and few governments maintain their power for long with clean hands.

The Israeli contrast –narratives of desperate Jewish refugees throwing cans at soldiers seventy years ago, told to rally support for Jewish soldiers shooting desperate refugees throwing stones today – is particularly striking because the time and space are so compressed. But the essential contrast is so familiar as to be almost universal: virtually all national narratives include brave struggles against oppressive governments, and few governments maintain their power for long with clean hands. As I write, Israeli troops are massed on the no man’s land separating Israel from Gaza, shooting tear gas grenades and live ammunition at Palestinian refugees who are gathered on the other side, throwing rocks, burning tires, and seeking to breech the barriers and send thousands of men, women and children across.

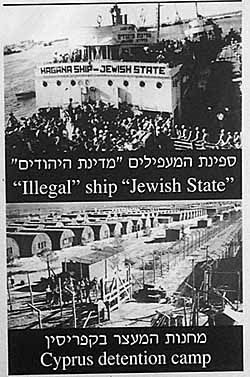

As I write, Israeli troops are massed on the no man’s land separating Israel from Gaza, shooting tear gas grenades and live ammunition at Palestinian refugees who are gathered on the other side, throwing rocks, burning tires, and seeking to breech the barriers and send thousands of men, women and children across. In Tel Aviv, the museum of the Hagganah, the Jewish army that faced British and Arab forces in the late 1940s, has a display honoring “Ha’apala – Clandestine (Illegal) Immigration, 1934-1944,” and two museums of the Etzel, the more radical Jewish underground, likewise celebrate the brave men and women who smuggled Jewish refugees into Palestine, defying the British army and even the Haggana, which in some periods helped the British, much as the Palestinian Authority’s police now work with Israeli forces to control illegal migration from the West Bank.

In Tel Aviv, the museum of the Hagganah, the Jewish army that faced British and Arab forces in the late 1940s, has a display honoring “Ha’apala – Clandestine (Illegal) Immigration, 1934-1944,” and two museums of the Etzel, the more radical Jewish underground, likewise celebrate the brave men and women who smuggled Jewish refugees into Palestine, defying the British army and even the Haggana, which in some periods helped the British, much as the Palestinian Authority’s police now work with Israeli forces to control illegal migration from the West Bank. Itzak Belfer, one of the passengers, describes how the British troops were massed on the deck of the destroyer, and someone brought up boxes of tin cans to throw at the soldiers. One of the men commanding the ship for the Palyam, the Jewish rebel navy, recalls: “We told them to give the British a hard time — to resist, to throw things, not let them board the ship, and maybe we could make it to the shore.”

Itzak Belfer, one of the passengers, describes how the British troops were massed on the deck of the destroyer, and someone brought up boxes of tin cans to throw at the soldiers. One of the men commanding the ship for the Palyam, the Jewish rebel navy, recalls: “We told them to give the British a hard time — to resist, to throw things, not let them board the ship, and maybe we could make it to the shore.” The British soldiers began to board, and Belfer, his voice thrilling at the memory, recalls throwing the cans of food at them: “That kind of can, when someone throws it, it can do a lot of damage.” Then the Palyam man on the ship’s bridge angrily turned the wheel and rammed their boat into the destroyer. “We were all knocked down,” Belfer says, but “We all felt like… ‘We did it! We showed them!’”

The British soldiers began to board, and Belfer, his voice thrilling at the memory, recalls throwing the cans of food at them: “That kind of can, when someone throws it, it can do a lot of damage.” Then the Palyam man on the ship’s bridge angrily turned the wheel and rammed their boat into the destroyer. “We were all knocked down,” Belfer says, but “We all felt like… ‘We did it! We showed them!’”