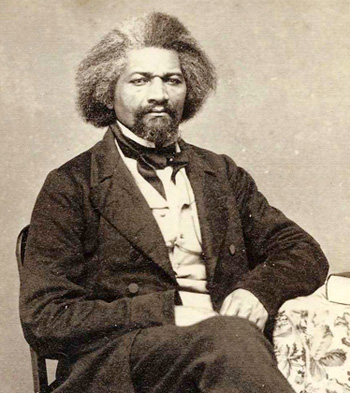

In 1869, amid calls to limit Chinese immigration, Frederick Douglass responded with one of his greatest speeches:

Men, like bees, want elbow room. When the hive is overcrowded, the bees will swarm, and will be likely to take up their abode where they find the best prospect for honey. In matters of this sort, men are very much like bees…. The same mighty forces which have swept to our shores the overflowing populations of Europe; which have reduced the people of Ireland three millions below its normal standard; will operate in a similar manner upon the hungry population of China and other parts of Asia. Home has its charms, and native land has its charms, but hunger, oppression, and destitution, will dissolve these charms and send men in search of new countries and new homes….

Men, like bees, want elbow room. When the hive is overcrowded, the bees will swarm, and will be likely to take up their abode where they find the best prospect for honey. In matters of this sort, men are very much like bees…. The same mighty forces which have swept to our shores the overflowing populations of Europe; which have reduced the people of Ireland three millions below its normal standard; will operate in a similar manner upon the hungry population of China and other parts of Asia. Home has its charms, and native land has its charms, but hunger, oppression, and destitution, will dissolve these charms and send men in search of new countries and new homes….

I have said that the Chinese will come, and have given some reasons why we may expect them in very large numbers in no very distant future. Do you ask, if I favor such immigration, I answer I would….

But are there not reasons against all this? Is there not such a law or principle as that of self-preservation? Does not every race owe something to itself? Should it not attend to the dictates of common sense…? Is there not such a thing as being more generous than wise? In the effort to promote civilization may we not corrupt and destroy what we have? Is it best to take on board more passengers than the ship will carry?

To all of this and more I have one among many answers, altogether satisfactory to me, though I cannot promise that it will be so to you.

I submit that this question of Chinese immigration should be settled upon higher principles than those of a cold and selfish expediency.

There are such things in the world as human rights. They rest upon no conventional foundation, but are external, universal, and indestructible. Among these, is the right of locomotion; the right of migration; the right which belongs to no particular race, but belongs alike to all and to all alike. It is the right you assert by staying here, and your fathers asserted by coming here…. I know of no rights of race superior to the rights of humanity, and when there is a supposed conflict between human and national rights, it is safe to go to the side of humanity. I have great respect for the blue eyed and light haired races of America. They are a mighty people. In any struggle for the good things of this world they need have no fear. They have no need to doubt that they will get their full share.

But I reject the arrogant and scornful theory by which they would limit migratory rights, or any other essential human rights to themselves, and which would make them the owners of this great continent to the exclusion of all other races of men.

I want a home here not only for the negro, the mulatto and the Latin races; but I want the Asiatic to find a home here in the United States, and feel at home here, both for his sake and for ours. Right wrongs no man. If respect is had to majorities, the fact that only one fifth of the population of the globe is white, the other four fifths are colored, ought to have some weight and influence in disposing of this and similar questions. It would be a sad reflection upon the laws of nature and upon the idea of justice, to say nothing of a common Creator, if four fifths of mankind were deprived of the rights of migration to make room for the one fifth….

So much for what is right; now let us see what is wise.

I hold that a liberal and brotherly welcome to all who are likely to come to the United states, is the only wise policy which this nation can adopt….

The apprehension that we shall be swamped or swallowed up by Mongolian civilization… does not seem entitled to much respect. Though they come as the waves come, we shall be stronger if we receive them as friends and give them a reason for loving our country and our institutions. They will find here a deeply rooted, indigenous, growing civilization, augmented by an ever increasing stream of immigration from Europe; and possession is nine points of the law in this case, as well as in others. They will come as strangers, we are at home. They will come to us, not we to them. They will come in their weakness, we shall meet them in our strength. They will come as individuals, we will meet them in multitudes, and with all the advantages of organization. Chinese children are in American schools in San Francisco, none of our children are in Chinese schools, and probably never will be, though in some things they might well teach us valuable lessons. Contact with these yellow children of The Celestial Empire would convince us that the points of human difference, great as they, upon first sight, seem, are as nothing compared with the points of human agreement. Such contact would remove mountains of prejudice….

If it could be shown that any particular race of men are literally incapable of improvement, we might hesitate to welcome them here. But no such men are anywhere to be found, and if there were, it is not likely that they would ever trouble us with their presence. The fact that the Chinese and other nations desire to come and do come, is a proof of their fitness to come….

I close these remarks as I began. If our action shall be in accordance with the principles of justice, liberty, and perfect human equality, no eloquence can adequately portray the greatness and grandeur of the future of the Republic.

We shall spread the network of our science and civilization over all who seek their shelter whether from Asia, Africa, or the Isles of the sea. We shall mold them all, each after his kind, into Americans; Indian and Celt; Negro and Saxon; Latin and Teuton; Mongolian and Caucasian; Jew and Gentile; all shall here bow to the same law, speak the same language, support the same Government, enjoy the same liberty, vibrate with the same national enthusiasm, and seek the same national ends.

Frederick Douglass, 1869.

I spent my second day in Hebron walking around, taking pictures, getting a better sense of where everything was. I went through a couple of full-scale checkpoints with turnstiles and metal detectors, and others with just a couple of soldiers with automatic rifles, and wherever I went they waved me through with a smile, even when I set off the metal detectors — I was asked my nationality a couple of times and once asked for my passport, but just to see I had one, not to open it and check my photo… because I was obviously a tourist and everybody wants more of those.

I spent my second day in Hebron walking around, taking pictures, getting a better sense of where everything was. I went through a couple of full-scale checkpoints with turnstiles and metal detectors, and others with just a couple of soldiers with automatic rifles, and wherever I went they waved me through with a smile, even when I set off the metal detectors — I was asked my nationality a couple of times and once asked for my passport, but just to see I had one, not to open it and check my photo… because I was obviously a tourist and everybody wants more of those. the hills above… it’s weird and fascinating, because these inimical populations are completely intertwined, sometimes on different floors of the same house. And no one was bothering me — some people didn’t return my hellos, but the soldiers were consistently polite and cheerful, and when I asked if I could take their picture they said, “Sure, you can do anything you want…”

the hills above… it’s weird and fascinating, because these inimical populations are completely intertwined, sometimes on different floors of the same house. And no one was bothering me — some people didn’t return my hellos, but the soldiers were consistently polite and cheerful, and when I asked if I could take their picture they said, “Sure, you can do anything you want…” They were very helpful, telling me how things were different in various periods, and we gradually made our way down the hill and back to the street in front of the Ibrahimi Mosque, which I had already walked up and down at least three times. They introduced me to a Palestinian man who runs a souvenir shop there, and while we were chatting the Israeli soldiers who were guarding that end of the street came over from the checkpoint and asked the women who they were and what they were doing. Then the women left to catch their ride back to Tel Aviv, and I had a coffee in the souvenir shop and headed back towards that street in front of the mosque, which was also the street to the hostel where I was staying…

They were very helpful, telling me how things were different in various periods, and we gradually made our way down the hill and back to the street in front of the Ibrahimi Mosque, which I had already walked up and down at least three times. They introduced me to a Palestinian man who runs a souvenir shop there, and while we were chatting the Israeli soldiers who were guarding that end of the street came over from the checkpoint and asked the women who they were and what they were doing. Then the women left to catch their ride back to Tel Aviv, and I had a coffee in the souvenir shop and headed back towards that street in front of the mosque, which was also the street to the hostel where I was staying… they’d seen me with. I said no, and they asked where I was going. I said I was going back to my hostel. They asked, “You are a Jew?” I said yes. They said, “You cannot go here.”

they’d seen me with. I said no, and they asked where I was going. I said I was going back to my hostel. They asked, “You are a Jew?” I said yes. They said, “You cannot go here.” I walked up the dirt road that led behind the mosque, into a thoroughly Arab neighborhood, wandered up dirt roads and down alleys, asked a couple of people for directions, and eventually wound my way down to the other end of the same street in front of the mosque… where another pair of soldiers who hadn’t seen me consorting with elderly Israeli peace observers waved me through with a smile. So that was that. I walked back through the market, bought a handful of almonds and a falafel sandwich with roast eggplant, hot pepper sauce, and pickled vegetables, retrieved my guitar and pack from the hostel, and caught a minibus to Bethlehem.

I walked up the dirt road that led behind the mosque, into a thoroughly Arab neighborhood, wandered up dirt roads and down alleys, asked a couple of people for directions, and eventually wound my way down to the other end of the same street in front of the mosque… where another pair of soldiers who hadn’t seen me consorting with elderly Israeli peace observers waved me through with a smile. So that was that. I walked back through the market, bought a handful of almonds and a falafel sandwich with roast eggplant, hot pepper sauce, and pickled vegetables, retrieved my guitar and pack from the hostel, and caught a minibus to Bethlehem.