I recently spent a couple of days in Łódź (which due to the oddities of Polish orthography is pronounced woodge, hence, as seat of the Polish film industry, Holly-Łódź), mostly to commune with the memory of  Julian Tuwim. Tuwim is a major figure in Polish literature, a poet, songwriter, and author whose songs and children’s poems are still widely known and performed, but I came across him because of one piece that – not accidentally – was left out of the official five-volume edition of his collected works.

Julian Tuwim. Tuwim is a major figure in Polish literature, a poet, songwriter, and author whose songs and children’s poems are still widely known and performed, but I came across him because of one piece that – not accidentally – was left out of the official five-volume edition of his collected works.

It was an impassioned essay called, “We, Polish Jews,” published in 1944 on the first anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, in a Polish-language newspaper in New York, where Tuwim was living in exile. (He described the city to a friend as “Łódź, but with elephantiasis.”) It was dedicated, “To my mother in Poland or her most beloved shade.” His mother had been shot in August 1942 during the extermination of the Otwock Ghetto, though I’m not clear whether he knew that when he wrote.

I ran across Tuwim’s essay while traveling in Israel/Palestine, and have run across it a couple of times since. The section that caught my attention, and that tends to get quoted is about his Jewish identity. He wrote that he was a Jew because of “blood” – not, he immediately added, in the sense of race, but “Exactly the opposite.” As he explained:

“There are two kinds of blood: blood in the veins and blood from the veins. The first is a bodily fluid; therefore its study is properly the province of the physiologists. Whoever ascribes to this blood any special attributes and mysterious powers other than its organic ones in consequence, as we are now seeing, turns cities into ruins, slaughters millions of people, and ultimately, as we shall see, will bring down slaughter upon his own tribe.”

The other kind of blood was what the Nazis were spilling, “not blood concealed in the arteries but blood on display.” And, he wrote, it was that blood, “the blood of the Jews (not ‘Jewish blood’),” that made him write as a Jew.

I’ve found myself repeating that formulation in various conversations, because I am working on a project on immigration, nationalism and borders, and didn’t want to write simply as a white American defending the rights of people from the southern hemisphere. My mother was a refugee from Nazi Vienna, my father’s parents were immigrants from Central Europe. I grew up on those stories, and I’m tracing them now, which means I’m thinking a lot about my own family history, and about the history of Jews in Central Europe – and the diaspora from Central Europe – and about the question of what it means if I say I am Jewish, and what it means if someone else says that.

Re-reading Tuwim’s essay, I’m struck by my original focus on the part about being Jewish, and the extent to which other writers have highlighted the same sections and phrases. Because that is not how Tuwim starts his piece. He begins by addressing the question of why he claims the pronoun “WE” for both Jews and Poles, writing, “Jews, whom I have always assured that I am a Pole, ask it of me; and now Poles, for the majority of whom I am and will remain a Jew, will ask it of me.” And, he wrote, “Here is my answer for all of them:

“I am a Pole because that’s how I like it. This is my completely private affair which I have no intention of explaining, clarifying, demonstrating or justifying to anyone. I do not divide Poles into ‘pure’ or ‘not pure,’ but leave that to the pure racists, to native and not native Hitlerites. I divide Poles, just as I do Jews and other peoples, into wise and stupid, polite and nasty, intelligent and dull, interesting and boring, injured and injuring, gentlemen and not gentlemen…”

“I am a Pole because that’s how I like it. This is my completely private affair which I have no intention of explaining, clarifying, demonstrating or justifying to anyone. I do not divide Poles into ‘pure’ or ‘not pure,’ but leave that to the pure racists, to native and not native Hitlerites. I divide Poles, just as I do Jews and other peoples, into wise and stupid, polite and nasty, intelligent and dull, interesting and boring, injured and injuring, gentlemen and not gentlemen…”

But, in fact, he does explain and clarify. He first notes that “to be a Pole…is neither an honor, nor a glory, nor a privilege. It is like breathing. I have not yet met a man who is proud that he breathes.” That said, it is his identity:

“A Pole—because I was born, grew up, matured and was educated in Poland; because in Poland I was happy and unhappy; because I want ultimately to return to Poland from exile even though heavenly delights were to be guaranteed me elsewhere….

“A Pole—because that is what I was called in Polish in my parents’ home; because from infancy I was nourished there on the Polish language; because my mother taught me Polish poetry and songs…; because that which became most important in my life—poetic creation—is unthinkable in any other language, no matter how fluently I might speak it….

“A Pole—because I have adopted from the Poles a certain number of their national vices. A Pole—because my hatred for Polish fascists is greater than for fascists of any other nationality. And I consider that a very important feature of my Polishness.

“But above all else… a Pole because that’s what I like to be.”

When Tuwim’s essay first appeared, it got a lot of attention and was translated into numerous languages. Not all the attention was positive; in Palestine, Zionist critics took him to task for declaring his Jewish allegiance only now, under pressure, after decades of writing as a Pole. He had never denied his Jewish ancestry and indeed had regularly made reference to it and written poems attacking antisemitism. But he had also written poems satirizing traditional Jews: “Dark, cunning, bearded/ With demented eyes/ In which there is an eternal fear… People/ Who do not know what a fatherland is/Because they have lived everywhere.” (You can find this and other poems in an article published by the American Association for Polish Jewish studies.)

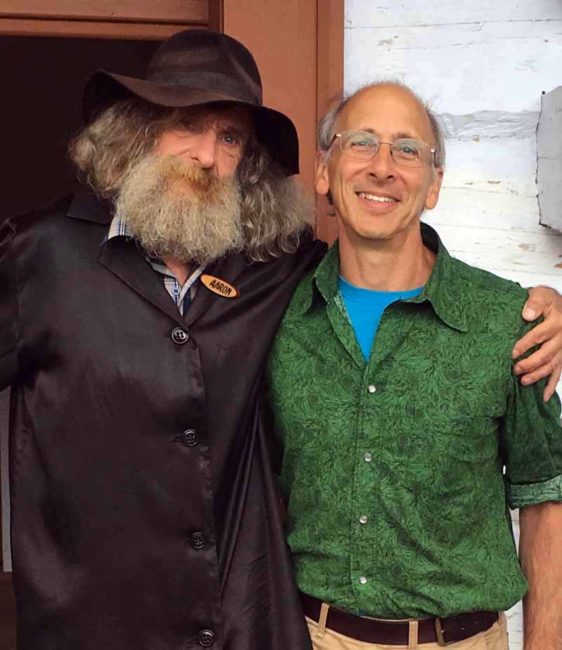

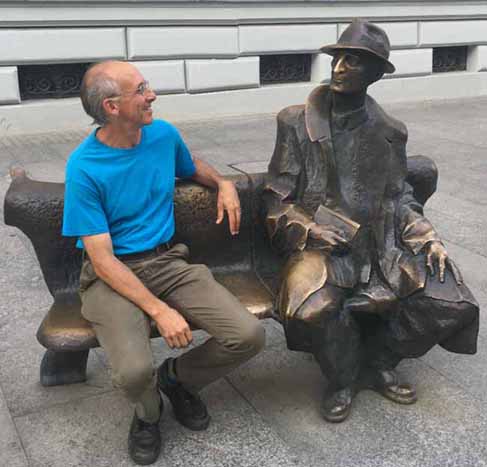

Today that criticism is often reversed, and Tuwim is taken to task for his naiveté about Poland—his passionate essay concludes with the prophesy that yellow stars will be adopted by the postwar Polish state as the highest badge of honor, pinned on the chests of military heroes, and that was not how things turned out. Poland would continue to be swept by waves of antisemitism, and in the years between the arrival of the Communist government and his death in 1953 Tuwim wrote very little and by some accounts was deeply depressed. But he lived those years in Poland and never seems to have considered leaving, and one of the main streets in the center of Łódź is called Tuwima, and his statue is on the city’s main pedestrian thoroughfare.

I’m not saying that’s a happy ending. It’s messy and complicated.

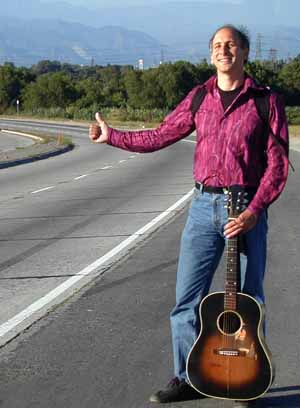

But some of the complications and messiness feel very familiar to me. As those of you who follow my Songobiography know, I have spent my life playing the folk and popular music of the United States. I’ve hitchhiked through all 48 contiguous states, and know the country well. It is my home and I feel very much part of it, for good and bad, better and worse. When a friend who has been active in the Polish klezmer revival (and who is not Jewish) asked if I ever played or wrote about Jewish music, my response was, “Well… I’ve written a book about Bob Dylan.” Who is, I would note, the patron saint of what is now called Americana music. Take that however you choose.

But some of the complications and messiness feel very familiar to me. As those of you who follow my Songobiography know, I have spent my life playing the folk and popular music of the United States. I’ve hitchhiked through all 48 contiguous states, and know the country well. It is my home and I feel very much part of it, for good and bad, better and worse. When a friend who has been active in the Polish klezmer revival (and who is not Jewish) asked if I ever played or wrote about Jewish music, my response was, “Well… I’ve written a book about Bob Dylan.” Who is, I would note, the patron saint of what is now called Americana music. Take that however you choose.

I was recently in Frankfurt, going through an exhibit on possessions looted or otherwise acquired by local gentiles and institutions—including the museum holding the exhibition—from local Jews who were deported or exterminated, and I was struck by a descriptive panel early in the exhibition which referred to “religious Jews and those first turned into Jews by the Nazis.”

I had never before seen that framing of identity, but it immediately struck home, because that was essentially my mother’s story. Her parents were Viennese socialists who dismissed religion as medieval superstition. I am not going to call them “assimilated,” because that word suggests they were somehow less Viennese than their socialist, atheist friends whose ancestors were Catholic. It is like the suggestion that someone in the United States who has one African and seven European great-grandparents is “passing” if she says she is European. It is letting the racists set the terms, and I won’t do that. I cannot deny the power or harm of the racist taxonomies, but I can point out that they are racist and refuse to use them.

My father grew up in Brooklyn, and was far more affected by antisemitism than my mother, the refugee from Nazi Vienna. For her, the racists were the Nazis. For him, they were the kids on his block. And, to make it messier, those kids weren’t unhyphenated Americans. They were all from families of recent immigrants, and when he went off to Washington Square College, he described the student body as “Jewish, Italian, Latin American, Greek, almost all Mediterraneans of one kind or another—and an occasional Christian blond, whom we tended to think of and speak of as the ‘white men’.”

Meanwhile, my mother grew up thoroughly Viennese, daughter of two physicians, one of whom was also a concert-quality pianist, immersed in Mozart, Goethe, the earthy Viennese street dialect, and the certainty that she was at the cultural center of the universe. Her childhood foods weren’t latkes and gefilte fish; they were schnitzel, Kaiserschmarrn, and pastries slathered in whipped cream. When the Nazis labeled her a Jew, that changed the course of her life but didn’t change how she thought about herself. She felt rejected by Vienna and often referred to herself not as Viennese but as European, but her views remained thoroughly Viennese, and socialist, and atheist.

Meanwhile, my mother grew up thoroughly Viennese, daughter of two physicians, one of whom was also a concert-quality pianist, immersed in Mozart, Goethe, the earthy Viennese street dialect, and the certainty that she was at the cultural center of the universe. Her childhood foods weren’t latkes and gefilte fish; they were schnitzel, Kaiserschmarrn, and pastries slathered in whipped cream. When the Nazis labeled her a Jew, that changed the course of her life but didn’t change how she thought about herself. She felt rejected by Vienna and often referred to herself not as Viennese but as European, but her views remained thoroughly Viennese, and socialist, and atheist.

When I graduated high school, one of my college applications had a line asking my religion. Being less sure than my mother, I wrote “agnostic.” That was fine with her, but not with my father. He said, “That’s not what they’re asking,” and told the story of applying to the Brooklyn Athletic Club, responding to the question of religion by saying “atheist,” and having the young man behind the desk smirk and write, “Jew.”

So I’m here communing with the ghost of Julian Tuwim, who insisted he was Polish because he liked to be, and Jewish because Hitler was killing millions of Jews. That formulation bothers me, and makes sense to me. It’s not my formulation, and I have problems with a lot of what Tuwim wrote, both politically and aesthetically. But that essay suggested some different ways of framing these subjects, made me wrestle with some new questions, and helped me clarify my own thinking.

It also led me to study Tuwim’s life and work, which among other things suggested what his response would be to my disagreements: one of his most famous compositions is titled “A Poem Wherein the Author Politely but Firmly Requests a Multitude of Fellows to Kiss His Ass.” (There is a nice modern cabaret version — and yes, the list of “fellows,” includes both antisemites and Jews.)

And lastly… in case there aren’t already enough ironic notes in this story… the Lonely Planet guidebook to Poland cheerfully reports that there is a local custom of rubbing the nose of Tuvim’s statue for luck. The Jew’s nose.

996 other Viennese Jews, on November 29, 1941. I wasn’t sure why I wanted to go there, but now I know – it was a powerful experience to be where I know a particular family member was killed, on a particular day.

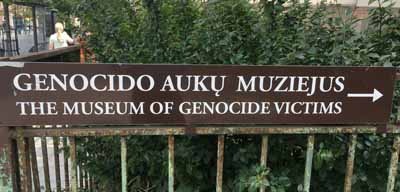

996 other Viennese Jews, on November 29, 1941. I wasn’t sure why I wanted to go there, but now I know – it was a powerful experience to be where I know a particular family member was killed, on a particular day. …the use of the word “genocide,” and specifically the use of Jewish deaths in service of the narrative of non-Jewish Lithuanian suffering is striking. For example, the panel giving numbers of Lithuanians killed: First, during almost fifty years under the Soviets between 1940-1990: 20-25,000 “prisoners who died”; 28,000 “died in deportation”; 21,500 “Partisans and their supporters killed.” Then, during the four years of German occupation between 1941-44: “240,000 killed (including about 200,000 Jews).” In parenthesis.

…the use of the word “genocide,” and specifically the use of Jewish deaths in service of the narrative of non-Jewish Lithuanian suffering is striking. For example, the panel giving numbers of Lithuanians killed: First, during almost fifty years under the Soviets between 1940-1990: 20-25,000 “prisoners who died”; 28,000 “died in deportation”; 21,500 “Partisans and their supporters killed.” Then, during the four years of German occupation between 1941-44: “240,000 killed (including about 200,000 Jews).” In parenthesis. I came to Lithuania following the story of my mother’s younger cousin Jutte, bringing her picture and the story of how she got stuck in Vienna, and the number of the transport that brought her to Kaunas, and the date when the 998 Viennese Jews on that train were chased up the hill at the Ninth Fort, pushed into mass graves, and shot – or in some cases shot, then pushed into mass graves. I wondered if the museum might be interested in having a copy of the photograph of Jutte and her mother, Gustl.

I came to Lithuania following the story of my mother’s younger cousin Jutte, bringing her picture and the story of how she got stuck in Vienna, and the number of the transport that brought her to Kaunas, and the date when the 998 Viennese Jews on that train were chased up the hill at the Ninth Fort, pushed into mass graves, and shot – or in some cases shot, then pushed into mass graves. I wondered if the museum might be interested in having a copy of the photograph of Jutte and her mother, Gustl. It gives the numbers of Lithuanian Jews killed, and displays personal items – eye glasses, shaving brushes, a pair of child’s shoes – found in the mass graves. It is a touching display. Not one Jew is named.

It gives the numbers of Lithuanian Jews killed, and displays personal items – eye glasses, shaving brushes, a pair of child’s shoes – found in the mass graves. It is a touching display. Not one Jew is named. There is a second museum in the fort itself, for those who wish to delve deeper. It does include rooms with photographs of individual Jews, their names, their stories. There is a powerful display on a transport of 878 French Jews killed here in 1944, the walls lined with named photographs, sponsored by “Les Familles et Amis des Déportés du Convoi 73, Paris (France).” There is a room about the Kaunas ghetto, with family pictures, names, and stories from survivors. There is a room about the escape of 64 prisoners who were brought in 1943 to burn the thousands of corpses, naming them and noting that 60 were Jews, along with three Russians and a Pole. There is a room with stories of survivors, saying what happened to them in later years. There is a room about the Japanese consul who in defiance of his government provided 6,000 Jews with exit visas. There is a room about “Lithuanians, the Saviours of the Jews,” with stories of non-Jewish Lithuanians who hid or helped their Jewish neighbors. And there is a room about Hitler and the genocide of European Jews, with names of 1,344 Jews from various parts of Europe who were killed here, each with their age and home town. Jutta and Gustl were not included – I looked for them, and the omission bothered me. But to continue…

There is a second museum in the fort itself, for those who wish to delve deeper. It does include rooms with photographs of individual Jews, their names, their stories. There is a powerful display on a transport of 878 French Jews killed here in 1944, the walls lined with named photographs, sponsored by “Les Familles et Amis des Déportés du Convoi 73, Paris (France).” There is a room about the Kaunas ghetto, with family pictures, names, and stories from survivors. There is a room about the escape of 64 prisoners who were brought in 1943 to burn the thousands of corpses, naming them and noting that 60 were Jews, along with three Russians and a Pole. There is a room with stories of survivors, saying what happened to them in later years. There is a room about the Japanese consul who in defiance of his government provided 6,000 Jews with exit visas. There is a room about “Lithuanians, the Saviours of the Jews,” with stories of non-Jewish Lithuanians who hid or helped their Jewish neighbors. And there is a room about Hitler and the genocide of European Jews, with names of 1,344 Jews from various parts of Europe who were killed here, each with their age and home town. Jutta and Gustl were not included – I looked for them, and the omission bothered me. But to continue… At the back of that room is a curtain, and if you go through there is a smaller room with a film showing the testimony of eight Lithuanian soldiers who were sentenced to death by the Soviet government in 1962 for participating in Nazi-organized massacres. One mimes standing at the edge of the mass graves and shooting down into the crowds of people, and explains how he would sell items he picked off the victims to buy a drink afterwards because “when you do such kind of thing you need to wet your whistle.”

At the back of that room is a curtain, and if you go through there is a smaller room with a film showing the testimony of eight Lithuanian soldiers who were sentenced to death by the Soviet government in 1962 for participating in Nazi-organized massacres. One mimes standing at the edge of the mass graves and shooting down into the crowds of people, and explains how he would sell items he picked off the victims to buy a drink afterwards because “when you do such kind of thing you need to wet your whistle.” At the Ninth Fort there are memorial stones placed by the city of Frankfurt in memory of the Jews transported from there to Kaunas; by the Families and Friends of the Jews transported and killed from France; by the city of Berlin in memory of 1000 Jewish children, women and men transported on Nov 17, 1941 and killed here on Nov 25; by the city of Munich in memory of 1000 Jews transported from there on November 20, 1941, and killed here five days later. There is no stone from Austria, or from the city of Vienna, commemorating the transport on November 23 that included my cousins. Like the Lithuanians, the Austrians prefer to recall the Nazi period as their own tragedy, not a Jewish tragedy. They do not deny that Jews were particularly selected for extermination, but they have their own issues, and feel we must remember it was a tough time, and everybody suffered…

At the Ninth Fort there are memorial stones placed by the city of Frankfurt in memory of the Jews transported from there to Kaunas; by the Families and Friends of the Jews transported and killed from France; by the city of Berlin in memory of 1000 Jewish children, women and men transported on Nov 17, 1941 and killed here on Nov 25; by the city of Munich in memory of 1000 Jews transported from there on November 20, 1941, and killed here five days later. There is no stone from Austria, or from the city of Vienna, commemorating the transport on November 23 that included my cousins. Like the Lithuanians, the Austrians prefer to recall the Nazi period as their own tragedy, not a Jewish tragedy. They do not deny that Jews were particularly selected for extermination, but they have their own issues, and feel we must remember it was a tough time, and everybody suffered… one photograph that, if you get close enough to read the minimal caption, turns out to show “the exhumation of remains of Soviet prisoners of war.” They aren’t denying that there were Soviet deaths in the Nazi period. If asked, I’m sure they would acknowledge that the Nazis killed millions of Soviet citizens, including some in Lithuania. That’s just not the story this museum is here to tell.

one photograph that, if you get close enough to read the minimal caption, turns out to show “the exhumation of remains of Soviet prisoners of war.” They aren’t denying that there were Soviet deaths in the Nazi period. If asked, I’m sure they would acknowledge that the Nazis killed millions of Soviet citizens, including some in Lithuania. That’s just not the story this museum is here to tell. This particular mosque apparently dates from the 18th century, but the community that built it has been in the region since the mid-17th century. They are Tatars, descendants of the Golden Horde that reached Eastern Europe shortly after the death of Genghis Khan. Since I’m traveling here as part of a project on borders and migration, and in particular looking into my own family’s history, when I read about the Tatars I immediately wondered what happened to them during the Nazi occupation.

This particular mosque apparently dates from the 18th century, but the community that built it has been in the region since the mid-17th century. They are Tatars, descendants of the Golden Horde that reached Eastern Europe shortly after the death of Genghis Khan. Since I’m traveling here as part of a project on borders and migration, and in particular looking into my own family’s history, when I read about the Tatars I immediately wondered what happened to them during the Nazi occupation. Robertson also writes that the Tatar Mufti of Poland, Jacob Szynkiewicz, helped protect the Karaite Jews by calling Goebbels to make the case that they were racially Turkic. I haven’t found corroboration of that particular story, but there is plenty of evidence that the Nazis considered the Karaim related to the Tatars both by ancestry and as communities that interacted on a regular basis – and therefore (except in a few notable instances) did not subject them to ghettoization or extermination. As a result, some Jews – meaning Ashkenazim – also managed to survive the holocaust by passing as Jews – meaning Karaim.

Robertson also writes that the Tatar Mufti of Poland, Jacob Szynkiewicz, helped protect the Karaite Jews by calling Goebbels to make the case that they were racially Turkic. I haven’t found corroboration of that particular story, but there is plenty of evidence that the Nazis considered the Karaim related to the Tatars both by ancestry and as communities that interacted on a regular basis – and therefore (except in a few notable instances) did not subject them to ghettoization or extermination. As a result, some Jews – meaning Ashkenazim – also managed to survive the holocaust by passing as Jews – meaning Karaim. tour of the mosque in Kruszyniany was conducted entirely in Polish, so I understood virtually nothing, but I did catch the words, “Charles Bronson…Charles Buchinski.” I assumed the guide was claiming Bronson as a Tatar, so checked and found that yes, indeed, his father was apparently a Tatar from Lithuania, and this touch of Mongolian heritage presumably was what made him so easy to cast as a Native American…

tour of the mosque in Kruszyniany was conducted entirely in Polish, so I understood virtually nothing, but I did catch the words, “Charles Bronson…Charles Buchinski.” I assumed the guide was claiming Bronson as a Tatar, so checked and found that yes, indeed, his father was apparently a Tatar from Lithuania, and this touch of Mongolian heritage presumably was what made him so easy to cast as a Native American… On a more serious note, the Tatars have recently been caught up in the anti-Muslim violence sweeping Europe. A mosque built by Tatars in Gdansk in the 1990s was firebombed in 2013, and in 2014 the historic mosque and cemetery I visited in Krusziniany were defaced with anti-Muslim slogans and a drawing of a pig. Which is ugly, and the ugliness is underlined by a story in the New York Times that quotes local Tatars blaming the violence on the influx of Muslim immigrants, which they see as raising justifiable concern among Poles that is causing friction where none existed before.

On a more serious note, the Tatars have recently been caught up in the anti-Muslim violence sweeping Europe. A mosque built by Tatars in Gdansk in the 1990s was firebombed in 2013, and in 2014 the historic mosque and cemetery I visited in Krusziniany were defaced with anti-Muslim slogans and a drawing of a pig. Which is ugly, and the ugliness is underlined by a story in the New York Times that quotes local Tatars blaming the violence on the influx of Muslim immigrants, which they see as raising justifiable concern among Poles that is causing friction where none existed before. , two of the five synagogues are even still there… but the synagogues are abandoned and boarded up, because the Jews who used to be almost a third of the population are not there anymore, nor are their descendants… and same in Lesko, where 70% of the town used to be Jewish, and now the only remaining synagogue is an art gallery, and much of the art is Christs and Madonnas and saints… and I recently posted a funny story about

, two of the five synagogues are even still there… but the synagogues are abandoned and boarded up, because the Jews who used to be almost a third of the population are not there anymore, nor are their descendants… and same in Lesko, where 70% of the town used to be Jewish, and now the only remaining synagogue is an art gallery, and much of the art is Christs and Madonnas and saints… and I recently posted a funny story about  Nation-State Bill, which says “the right to national self-determination in Israel is unique to the Jewish people” — which is another way of saying if you are an Arab Israeli, you may live there but it is not your country.

Nation-State Bill, which says “the right to national self-determination in Israel is unique to the Jewish people” — which is another way of saying if you are an Arab Israeli, you may live there but it is not your country.

skansen reflects the multi-cultural nature of rural Galicia in 1900, with sections showing the lifestyles of the Eastern Orthodox Boyks and Lemks, the Catholic (now often called “ethnic”) Poles… and a large wooden synagogue and two “Jewish” houses on the main square.

skansen reflects the multi-cultural nature of rural Galicia in 1900, with sections showing the lifestyles of the Eastern Orthodox Boyks and Lemks, the Catholic (now often called “ethnic”) Poles… and a large wooden synagogue and two “Jewish” houses on the main square. He spoke some English, and enthusiastically showed us around: the bedroom, for example, where he pointed out the curling iron for shaping the men’s peyos and the peculiarity of the marital bed, which could be separated when the Jewish woman had her period or had given birth, hence was “unclean,” and pushed together again after she had bathed in the mikveh. He showed us the special dishes for meat and dairy, and the sabbath dishes. All very strange and exotic…

He spoke some English, and enthusiastically showed us around: the bedroom, for example, where he pointed out the curling iron for shaping the men’s peyos and the peculiarity of the marital bed, which could be separated when the Jewish woman had her period or had given birth, hence was “unclean,” and pushed together again after she had bathed in the mikveh. He showed us the special dishes for meat and dairy, and the sabbath dishes. All very strange and exotic…