I have been writing for five months about the siege and assault on Gaza, but most of that writing feels too immediate to post here. I’m making an exception for this piece, which has deeper personal resonance and relates to earlier posts:

The Washington Post today has personal reminiscences from 14 Gazan refugees about places that have been destroyed in the last  five months: the region’s only university; the oldest Christian church; a mosque; the zoo; a cultural center; an orphanage; a park—the trees bulldozed—and smaller places: a bakery, a pizzeria…

five months: the region’s only university; the oldest Christian church; a mosque; the zoo; a cultural center; an orphanage; a park—the trees bulldozed—and smaller places: a bakery, a pizzeria…

I think about my mother’s family being forced to flee Vienna in 1938, and her enduring love for the places where she grew up… and the fact that decades later, when my sister and I were old enough, she could take us back there, and show us those places.

The Israeli destruction of Gaza goes way beyond the immediate human cost — the 30,000 people killed, the two million homeless and starving under constant assault and bombardment. It is a concerted, intentional effort to wipe out memories, to destroy not only the past but the future; to convince Palestinians who have yet again been driven from their homes that this time there will be no homes to which they might hope to return.

There is nothing “defensive” about the razing of every significant structure in northern Gaza. Some of the buildings were destroyed while people were sheltering in them; some were destroyed when they were empty. Some are being destroyed after serving as temporary bases for Israeli soldiers, who eat the food left in the kitchens, take family possessions as souvenirs, then set the rest on fire when they leave. (That is not a slander; it is from videos the soldiers themselves are posting, proudly.)

The Post story refers to this as “urbicide,” the destruction of a city, but it is more than that, and does not require an academic term. It is an attempt to destroy memory; to destroy culture; to destroy hope.

The Post story refers to this as “urbicide,” the destruction of a city, but it is more than that, and does not require an academic term. It is an attempt to destroy memory; to destroy culture; to destroy hope.

None of this is accidental; the Israeli government has repeated for decades that Palestinians do not exist, that they are simply “Arabs,” with no particular connection to the homes or land from which they are expelled. When people were driven from their homes in Haifa, they took their door keys with them, and those keys remain a symbol–the image is everywhere in the occupied territories and refugee camps–for their hope of someday returning.

What is happening in Gaza is an attempt at complete erasure. Some of the two million people may survive; some may even remain within borders policed by Israel; but the Israeli state is trying to ensure there will be no place to which they can return — that the only “return” is of the Jews to their ancient homeland, in which some “Arabs” can remain as guest workers, but without a history.

A founding myth of Israel is that the Jews were a people without land who came to a land without people. That was always a lie, always an invention to mask an ongoing policy of appropriation, expulsion, denial, and erasure. In Gaza, as we watch, that policy is being carried to its logical conclusion: utter destruction, wiping out not only the people but the evidence of their prior existence.

The Washington Post piece has the power of personal connection: ordinary people recalling places that they loved, that made their homes a home. The introductory paragraph refers to the common description of Gaza in the past two decades as an “open air prison,” and counters with an insistence that, true as that was in some respects, it was also a place where people lived and loved.

Vienna was not a paradise for Jews; it had a deep history of antisemitism, and my mother had direct memories of the Nazis marching, the books being burnt, the Jews being forced to scrub the streets; but when she took us back there, it was to share the Prater, the Riesenrad, the Stephansplatz, the Brueghels in the national museum, the restaurants where you could order a schnitzel and hear the cook hammering in the kitchen.

Vienna was not a paradise for Jews; it had a deep history of antisemitism, and my mother had direct memories of the Nazis marching, the books being burnt, the Jews being forced to scrub the streets; but when she took us back there, it was to share the Prater, the Riesenrad, the Stephansplatz, the Brueghels in the national museum, the restaurants where you could order a schnitzel and hear the cook hammering in the kitchen.

That is an authentic Jewish past: not the poisonous Wagnerian myth of a past when our ancestors were warrior kings, but the real past of personal connections and memories. It is a past that Zionist propagandists have often sought to destroy and replace with a myth that we were never happy in Europe, that we could never truly belong anywhere but Israel. What is happening now in Gaza is inseparable from that effort; it requires erasing my true past in favor of a myth, and erasing the past of the people who were living in Palestine before my relatives settled there in the twentieth century.

My mother grew up in Vienna. She was 14 years old when the German army marched in and was greeted with parades. She spent the next weeks running errands for her parents because it was dangerous for them to be out in the streets. They were not only Jewish, but longtime leftists, and they realized immediately that they would have to leave. It was easier in those first months, and they got out and got to the United States. My grandfather helped other relatives to get out. He tried to help his favorite brother and my mother’s favorite cousin, but for various reasons they did not want to leave until it was too late. They were shipped east in the cattle cars, and murdered.

My mother grew up in Vienna. She was 14 years old when the German army marched in and was greeted with parades. She spent the next weeks running errands for her parents because it was dangerous for them to be out in the streets. They were not only Jewish, but longtime leftists, and they realized immediately that they would have to leave. It was easier in those first months, and they got out and got to the United States. My grandfather helped other relatives to get out. He tried to help his favorite brother and my mother’s favorite cousin, but for various reasons they did not want to leave until it was too late. They were shipped east in the cattle cars, and murdered.

, two of the five synagogues are even still there… but the synagogues are abandoned and boarded up, because the Jews who used to be almost a third of the population are not there anymore, nor are their descendants… and same in Lesko, where 70% of the town used to be Jewish, and now the only remaining synagogue is an art gallery, and much of the art is Christs and Madonnas and saints… and I recently posted a funny story about

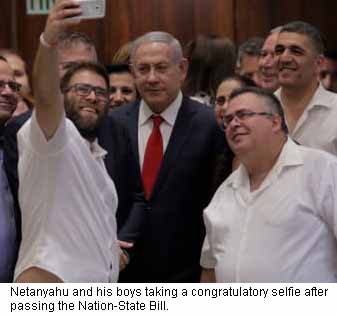

, two of the five synagogues are even still there… but the synagogues are abandoned and boarded up, because the Jews who used to be almost a third of the population are not there anymore, nor are their descendants… and same in Lesko, where 70% of the town used to be Jewish, and now the only remaining synagogue is an art gallery, and much of the art is Christs and Madonnas and saints… and I recently posted a funny story about  Nation-State Bill, which says “the right to national self-determination in Israel is unique to the Jewish people” — which is another way of saying if you are an Arab Israeli, you may live there but it is not your country.

Nation-State Bill, which says “the right to national self-determination in Israel is unique to the Jewish people” — which is another way of saying if you are an Arab Israeli, you may live there but it is not your country.