I recently spent a day at the Ninth Fort in Kaunas, Lithuania, where my mother’s favorite cousin, Jutte, was shot at age 16, along with her mother and  996 other Viennese Jews, on November 29, 1941. I wasn’t sure why I wanted to go there, but now I know – it was a powerful experience to be where I know a particular family member was killed, on a particular day.

996 other Viennese Jews, on November 29, 1941. I wasn’t sure why I wanted to go there, but now I know – it was a powerful experience to be where I know a particular family member was killed, on a particular day.

And it made me angry, because so much of the Ninth Fort museum and the whole project of memorializing the history of genocide and terror in Lithuania is dedicated to keeping the hundreds of thousands of Jews killed here in the Nazi era from overshadowing the murders and terror visited on non-Jewish Lithuanians during the Soviet eras.

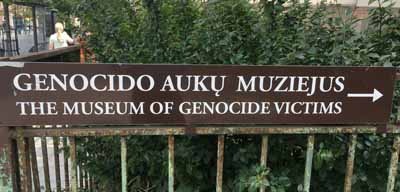

Two days earlier I visited the Museum of Genocide Victims in Vilnius, which dedicates one room to the genocide of the Lithuanian Jews and dozens to the oppression of Lithuanian non-Jews by the Soviets. (In response to years of protests, this museum has officially been renamed the Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights, but all its signage still says the Museum of Genocide Victims.) In fairness, the museum is in a building that served for decades as a KGB prison, where thousands of Lithuanians were held, tortured, and in some cases killed. That story is real, and deserves to be commemorated. But…

…the use of the word “genocide,” and specifically the use of Jewish deaths in service of the narrative of non-Jewish Lithuanian suffering is striking. For example, the panel giving numbers of Lithuanians killed: First, during almost fifty years under the Soviets between 1940-1990: 20-25,000 “prisoners who died”; 28,000 “died in deportation”; 21,500 “Partisans and their supporters killed.” Then, during the four years of German occupation between 1941-44: “240,000 killed (including about 200,000 Jews).” In parenthesis.

…the use of the word “genocide,” and specifically the use of Jewish deaths in service of the narrative of non-Jewish Lithuanian suffering is striking. For example, the panel giving numbers of Lithuanians killed: First, during almost fifty years under the Soviets between 1940-1990: 20-25,000 “prisoners who died”; 28,000 “died in deportation”; 21,500 “Partisans and their supporters killed.” Then, during the four years of German occupation between 1941-44: “240,000 killed (including about 200,000 Jews).” In parenthesis.

Of course, it’s fair to argue that numbers are not the whole story – except, in the case of Jews, in this museum, numbers ARE the whole story. Not one Jewish Lithuanian is mentioned by name in the entire museum.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the power of naming since reading Ari Shavit’s book, “My Promised Land.” For those who don’t know it, it is a liberal Zionist’s exploration of Israeli history, which purports to fairly acknowledge the suffering of the Palestinians. But Shavit’s careful evenhandedness is consistently numeric and falls apart at the level of naming and specificity. In a long chapter on the terrorist bombings and killings of the 1930s, he scrupulously notes that there were more Palestinians killed by Jewish terrorists than Jews killed by Palestinians – but the Jewish victims are consistently named, along with their ages and details about who they were and what they were doing when they were killed (walking home from a movie, tending an orchard, studying), while the Palestinian victims are just numbers, only a couple named, no ages provided. I’m guessing Shavit did this unconsciously, but that’s not a defense: on the contrary, it underscores the degree to which Jews, for him, are individual human beings, while Palestinians are not.

After reading that book I started paying closer attention to when historical narratives include names, ages, photographs, and details of individual victims and when they only give numbers. It is an interesting exercise, and often very revealing – it is now common to read US historical narratives that refer to the genocide of Native Americans, but how many mention any of the murdered Native Americans by name?

I came to Lithuania following the story of my mother’s younger cousin Jutte, bringing her picture and the story of how she got stuck in Vienna, and the number of the transport that brought her to Kaunas, and the date when the 998 Viennese Jews on that train were chased up the hill at the Ninth Fort, pushed into mass graves, and shot – or in some cases shot, then pushed into mass graves. I wondered if the museum might be interested in having a copy of the photograph of Jutte and her mother, Gustl.

I came to Lithuania following the story of my mother’s younger cousin Jutte, bringing her picture and the story of how she got stuck in Vienna, and the number of the transport that brought her to Kaunas, and the date when the 998 Viennese Jews on that train were chased up the hill at the Ninth Fort, pushed into mass graves, and shot – or in some cases shot, then pushed into mass graves. I wondered if the museum might be interested in having a copy of the photograph of Jutte and her mother, Gustl.

Then I went through the museum at the entrance to the fort. The first section is a dramatic, full-room stained glass installation titled “Undefeated Lithuania.” Then we get the history of the first Soviet occupation, 1940-41, with photos and biographies of Lithuanians who were exiled or killed, and details about what happened to each of them. There is a panel on the “Priests’ Massacre in Budavone Forest,” showing the three priests who were killed. There is a panel on the “Massacre of Panevezys Physicians,” with names and photos of the four physicians who were tortured and killed. Then there are multiple panels on the deportations of Lithuanians during the second Soviet occupation, after 1944, with names, photos, and objects belonging to the victims, like the seven-string guitar V. Lapiusko brought with him to Siberia.

There is a display in this room about the Nazi period, with photographs of the Kaunas ghetto, yellow stars, and Jewish corpses.  It gives the numbers of Lithuanian Jews killed, and displays personal items – eye glasses, shaving brushes, a pair of child’s shoes – found in the mass graves. It is a touching display. Not one Jew is named.

It gives the numbers of Lithuanian Jews killed, and displays personal items – eye glasses, shaving brushes, a pair of child’s shoes – found in the mass graves. It is a touching display. Not one Jew is named.

There are pictures from Nazi extermination camps outside Lithuania: Ravensbruck, Bergen-Belsen, and Auschwitz-Birkenau. The photos are horrifying, but identified only by camp, except for a display titled “Lithuanian intellectuals at Stutthof concentration camp,” which includes names, photos, and biographies of the title figures, and mentions that 85,000 people were killed there, including 1,100 Lithuanians.

The Nazi display also includes one document that suggests why a patriotic Lithuanian museum might have problems with this period, and might want to shift the discussion from local details to the broader German genocide. It is a typed report from a German officer on July 11, 1941, explaining that a ghetto has been established for the remaining Jews in Kovno (Kaunas). The accompanying label translates a key paragraph: “In Kovno a total of 7,800 have now been killed—a portion through the pogrom, a portion shot by Lithuanian commandos. All corpses have been disposed of. Continued mass shootings are no longer possible. Instead I explained to a committee of Jews that up to now, we have not had a reason to intervene in the internal conflicts between the Lithuanians and the Jews…” Unlike every other display in the room, this document is labeled and translated only in English – not in Lithuanian.

There is a second museum in the fort itself, for those who wish to delve deeper. It does include rooms with photographs of individual Jews, their names, their stories. There is a powerful display on a transport of 878 French Jews killed here in 1944, the walls lined with named photographs, sponsored by “Les Familles et Amis des Déportés du Convoi 73, Paris (France).” There is a room about the Kaunas ghetto, with family pictures, names, and stories from survivors. There is a room about the escape of 64 prisoners who were brought in 1943 to burn the thousands of corpses, naming them and noting that 60 were Jews, along with three Russians and a Pole. There is a room with stories of survivors, saying what happened to them in later years. There is a room about the Japanese consul who in defiance of his government provided 6,000 Jews with exit visas. There is a room about “Lithuanians, the Saviours of the Jews,” with stories of non-Jewish Lithuanians who hid or helped their Jewish neighbors. And there is a room about Hitler and the genocide of European Jews, with names of 1,344 Jews from various parts of Europe who were killed here, each with their age and home town. Jutta and Gustl were not included – I looked for them, and the omission bothered me. But to continue…

There is a second museum in the fort itself, for those who wish to delve deeper. It does include rooms with photographs of individual Jews, their names, their stories. There is a powerful display on a transport of 878 French Jews killed here in 1944, the walls lined with named photographs, sponsored by “Les Familles et Amis des Déportés du Convoi 73, Paris (France).” There is a room about the Kaunas ghetto, with family pictures, names, and stories from survivors. There is a room about the escape of 64 prisoners who were brought in 1943 to burn the thousands of corpses, naming them and noting that 60 were Jews, along with three Russians and a Pole. There is a room with stories of survivors, saying what happened to them in later years. There is a room about the Japanese consul who in defiance of his government provided 6,000 Jews with exit visas. There is a room about “Lithuanians, the Saviours of the Jews,” with stories of non-Jewish Lithuanians who hid or helped their Jewish neighbors. And there is a room about Hitler and the genocide of European Jews, with names of 1,344 Jews from various parts of Europe who were killed here, each with their age and home town. Jutta and Gustl were not included – I looked for them, and the omission bothered me. But to continue…

At the back of that room is a curtain, and if you go through there is a smaller room with a film showing the testimony of eight Lithuanian soldiers who were sentenced to death by the Soviet government in 1962 for participating in Nazi-organized massacres. One mimes standing at the edge of the mass graves and shooting down into the crowds of people, and explains how he would sell items he picked off the victims to buy a drink afterwards because “when you do such kind of thing you need to wet your whistle.”

At the back of that room is a curtain, and if you go through there is a smaller room with a film showing the testimony of eight Lithuanian soldiers who were sentenced to death by the Soviet government in 1962 for participating in Nazi-organized massacres. One mimes standing at the edge of the mass graves and shooting down into the crowds of people, and explains how he would sell items he picked off the victims to buy a drink afterwards because “when you do such kind of thing you need to wet your whistle.”

I was in that section for fifteen minutes, and maybe two dozen people wandered through the first room, looked at the photos, looked at the quotations from Hitler, looked at the wall of names. Only a couple pulled back the curtain, and not one bothered to watch the film. I understand; there was a lot to see and watching a film takes time. Not one plaque or label anywhere else mentioned that Lithuanians were involved in any of the Nazi murders. I was taking note, because in the Vilnius genocide museum they use the same technique: the room on the Nazi period includes a video that mentions Lithuanian involvement in the murders, but you have to watch the video to get that information – the wall displays do not even hint at that possibility.

I’m not trying to make a point about the Lithuanians. I mentioned an Israeli historian above, and US historians. I’m making a point about how nationalists construct national narratives. Some are more subtle than others, but the process is pretty general.

At the Ninth Fort there are memorial stones placed by the city of Frankfurt in memory of the Jews transported from there to Kaunas; by the Families and Friends of the Jews transported and killed from France; by the city of Berlin in memory of 1000 Jewish children, women and men transported on Nov 17, 1941 and killed here on Nov 25; by the city of Munich in memory of 1000 Jews transported from there on November 20, 1941, and killed here five days later. There is no stone from Austria, or from the city of Vienna, commemorating the transport on November 23 that included my cousins. Like the Lithuanians, the Austrians prefer to recall the Nazi period as their own tragedy, not a Jewish tragedy. They do not deny that Jews were particularly selected for extermination, but they have their own issues, and feel we must remember it was a tough time, and everybody suffered…

At the Ninth Fort there are memorial stones placed by the city of Frankfurt in memory of the Jews transported from there to Kaunas; by the Families and Friends of the Jews transported and killed from France; by the city of Berlin in memory of 1000 Jewish children, women and men transported on Nov 17, 1941 and killed here on Nov 25; by the city of Munich in memory of 1000 Jews transported from there on November 20, 1941, and killed here five days later. There is no stone from Austria, or from the city of Vienna, commemorating the transport on November 23 that included my cousins. Like the Lithuanians, the Austrians prefer to recall the Nazi period as their own tragedy, not a Jewish tragedy. They do not deny that Jews were particularly selected for extermination, but they have their own issues, and feel we must remember it was a tough time, and everybody suffered…

Which is true enough, in its way. The Ninth Fort museum even has  one photograph that, if you get close enough to read the minimal caption, turns out to show “the exhumation of remains of Soviet prisoners of war.” They aren’t denying that there were Soviet deaths in the Nazi period. If asked, I’m sure they would acknowledge that the Nazis killed millions of Soviet citizens, including some in Lithuania. That’s just not the story this museum is here to tell.

one photograph that, if you get close enough to read the minimal caption, turns out to show “the exhumation of remains of Soviet prisoners of war.” They aren’t denying that there were Soviet deaths in the Nazi period. If asked, I’m sure they would acknowledge that the Nazis killed millions of Soviet citizens, including some in Lithuania. That’s just not the story this museum is here to tell.

History is always an effort to preserve and remember what is important from the past, which always requires selecting what is important, which always means what is important to us, whoever we may be. But this post is particularly about how national histories are framed to suit nationalist needs. The idea of a nation requires stories that define a national “us” and also make us feel good about being part of that “us.”

One of the most powerful ways of creating a unified us is by recalling the terrible things other people did to us, and how we survived and overcame those trials. That often requires a bit of creative amnesia, since other people often have their own horror stories in which we were the perpetrators. Some people just deny the ugly parts; some are more subtle and figure out ways to make them seem less ugly, or just less meaningful, or less visceral.

In the last few weeks I’ve visited Auschwitz and Majdanek, where far more people were killed than at the Ninth Fort, but neither of those visits hit me as hard as this one. Because this one is personal: I have the photo, the names, the dates, and my mother’s memory of her younger cousin and the crazy, sad story of how she ended up in Kaunas, and what happened to her here. I’m telling some of that story here, and will be writing more of it soon, because individual stories are powerful.

The people making these museums understand that. Their displays are full of individual heroes and martyrs. And, looked at another way, full of absences.

This particular mosque apparently dates from the 18th century, but the community that built it has been in the region since the mid-17th century. They are Tatars, descendants of the Golden Horde that reached Eastern Europe shortly after the death of Genghis Khan. Since I’m traveling here as part of a project on borders and migration, and in particular looking into my own family’s history, when I read about the Tatars I immediately wondered what happened to them during the Nazi occupation.

This particular mosque apparently dates from the 18th century, but the community that built it has been in the region since the mid-17th century. They are Tatars, descendants of the Golden Horde that reached Eastern Europe shortly after the death of Genghis Khan. Since I’m traveling here as part of a project on borders and migration, and in particular looking into my own family’s history, when I read about the Tatars I immediately wondered what happened to them during the Nazi occupation. Robertson also writes that the Tatar Mufti of Poland, Jacob Szynkiewicz, helped protect the Karaite Jews by calling Goebbels to make the case that they were racially Turkic. I haven’t found corroboration of that particular story, but there is plenty of evidence that the Nazis considered the Karaim related to the Tatars both by ancestry and as communities that interacted on a regular basis – and therefore (except in a few notable instances) did not subject them to ghettoization or extermination. As a result, some Jews – meaning Ashkenazim – also managed to survive the holocaust by passing as Jews – meaning Karaim.

Robertson also writes that the Tatar Mufti of Poland, Jacob Szynkiewicz, helped protect the Karaite Jews by calling Goebbels to make the case that they were racially Turkic. I haven’t found corroboration of that particular story, but there is plenty of evidence that the Nazis considered the Karaim related to the Tatars both by ancestry and as communities that interacted on a regular basis – and therefore (except in a few notable instances) did not subject them to ghettoization or extermination. As a result, some Jews – meaning Ashkenazim – also managed to survive the holocaust by passing as Jews – meaning Karaim. tour of the mosque in Kruszyniany was conducted entirely in Polish, so I understood virtually nothing, but I did catch the words, “Charles Bronson…Charles Buchinski.” I assumed the guide was claiming Bronson as a Tatar, so checked and found that yes, indeed, his father was apparently a Tatar from Lithuania, and this touch of Mongolian heritage presumably was what made him so easy to cast as a Native American…

tour of the mosque in Kruszyniany was conducted entirely in Polish, so I understood virtually nothing, but I did catch the words, “Charles Bronson…Charles Buchinski.” I assumed the guide was claiming Bronson as a Tatar, so checked and found that yes, indeed, his father was apparently a Tatar from Lithuania, and this touch of Mongolian heritage presumably was what made him so easy to cast as a Native American… On a more serious note, the Tatars have recently been caught up in the anti-Muslim violence sweeping Europe. A mosque built by Tatars in Gdansk in the 1990s was firebombed in 2013, and in 2014 the historic mosque and cemetery I visited in Krusziniany were defaced with anti-Muslim slogans and a drawing of a pig. Which is ugly, and the ugliness is underlined by a story in the New York Times that quotes local Tatars blaming the violence on the influx of Muslim immigrants, which they see as raising justifiable concern among Poles that is causing friction where none existed before.

On a more serious note, the Tatars have recently been caught up in the anti-Muslim violence sweeping Europe. A mosque built by Tatars in Gdansk in the 1990s was firebombed in 2013, and in 2014 the historic mosque and cemetery I visited in Krusziniany were defaced with anti-Muslim slogans and a drawing of a pig. Which is ugly, and the ugliness is underlined by a story in the New York Times that quotes local Tatars blaming the violence on the influx of Muslim immigrants, which they see as raising justifiable concern among Poles that is causing friction where none existed before. , two of the five synagogues are even still there… but the synagogues are abandoned and boarded up, because the Jews who used to be almost a third of the population are not there anymore, nor are their descendants… and same in Lesko, where 70% of the town used to be Jewish, and now the only remaining synagogue is an art gallery, and much of the art is Christs and Madonnas and saints… and I recently posted a funny story about

, two of the five synagogues are even still there… but the synagogues are abandoned and boarded up, because the Jews who used to be almost a third of the population are not there anymore, nor are their descendants… and same in Lesko, where 70% of the town used to be Jewish, and now the only remaining synagogue is an art gallery, and much of the art is Christs and Madonnas and saints… and I recently posted a funny story about  Nation-State Bill, which says “the right to national self-determination in Israel is unique to the Jewish people” — which is another way of saying if you are an Arab Israeli, you may live there but it is not your country.

Nation-State Bill, which says “the right to national self-determination in Israel is unique to the Jewish people” — which is another way of saying if you are an Arab Israeli, you may live there but it is not your country.

skansen reflects the multi-cultural nature of rural Galicia in 1900, with sections showing the lifestyles of the Eastern Orthodox Boyks and Lemks, the Catholic (now often called “ethnic”) Poles… and a large wooden synagogue and two “Jewish” houses on the main square.

skansen reflects the multi-cultural nature of rural Galicia in 1900, with sections showing the lifestyles of the Eastern Orthodox Boyks and Lemks, the Catholic (now often called “ethnic”) Poles… and a large wooden synagogue and two “Jewish” houses on the main square. He spoke some English, and enthusiastically showed us around: the bedroom, for example, where he pointed out the curling iron for shaping the men’s peyos and the peculiarity of the marital bed, which could be separated when the Jewish woman had her period or had given birth, hence was “unclean,” and pushed together again after she had bathed in the mikveh. He showed us the special dishes for meat and dairy, and the sabbath dishes. All very strange and exotic…

He spoke some English, and enthusiastically showed us around: the bedroom, for example, where he pointed out the curling iron for shaping the men’s peyos and the peculiarity of the marital bed, which could be separated when the Jewish woman had her period or had given birth, hence was “unclean,” and pushed together again after she had bathed in the mikveh. He showed us the special dishes for meat and dairy, and the sabbath dishes. All very strange and exotic…

nk, in Jordan, in refugee camps, and in a global diaspora. Some have famously kept the keys to the houses they or their grandparents left – the key has become a symbol of Palestinian return; some tell stories of visiting Haifa in later years, knocking on the doors of their houses and asking the Jewish owners if they could walk through the rooms, see if their family pictures were still on the walls, their rugs still on the floors; others have never set foot in Israel and talk longingly of visiting the places they heard of from their parents or grand-parents.

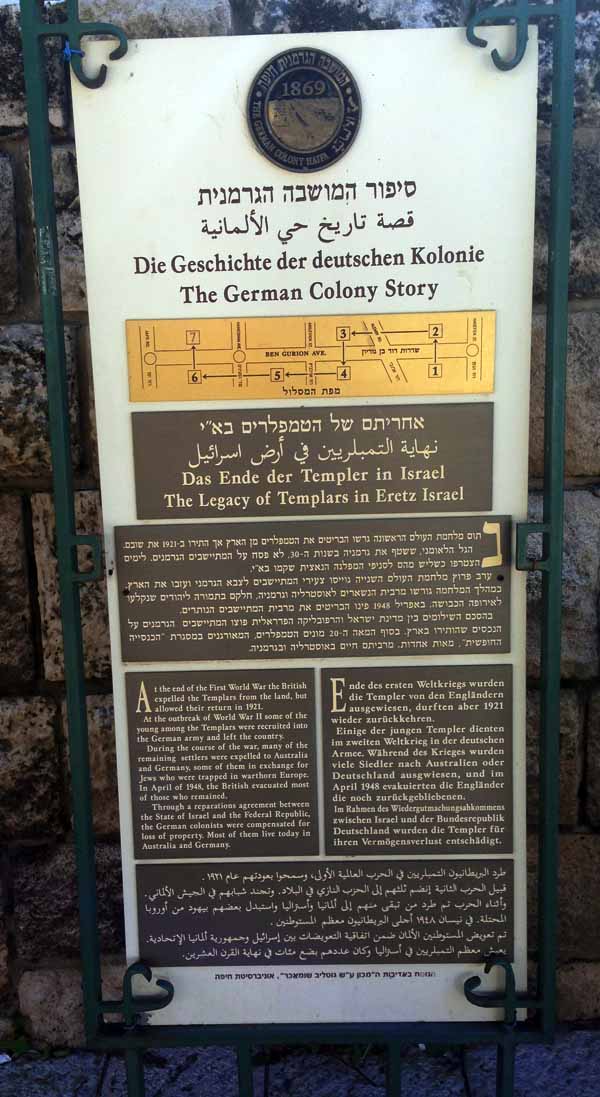

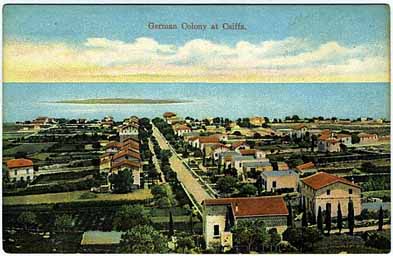

nk, in Jordan, in refugee camps, and in a global diaspora. Some have famously kept the keys to the houses they or their grandparents left – the key has become a symbol of Palestinian return; some tell stories of visiting Haifa in later years, knocking on the doors of their houses and asking the Jewish owners if they could walk through the rooms, see if their family pictures were still on the walls, their rugs still on the floors; others have never set foot in Israel and talk longingly of visiting the places they heard of from their parents or grand-parents. Which is why I was startled by an informational sign on Ben Gurion Avenue in Haifa telling “Die Geschichte der deutschen Kolonie/The German Colony Story,” and in particular about the Templars, a German Protestant group that settled there in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Which is why I was startled by an informational sign on Ben Gurion Avenue in Haifa telling “Die Geschichte der deutschen Kolonie/The German Colony Story,” and in particular about the Templars, a German Protestant group that settled there in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Karl Ruff, an architect born to Templar parents in Haifa in 1904, made contact with the German Nazis in 1931, two years before Hitler came to power, and helped form a core of support that grew into a full-blown Palestinian branch by 1933. A year later, Ludwig Buchhalter, a teacher at the Templar school in Jerusalem, was active in getting the German consul removed from office for having a Jewish wife, arguing “a person who has relations with Jewish circles cannot be loyal to German interests…”

Karl Ruff, an architect born to Templar parents in Haifa in 1904, made contact with the German Nazis in 1931, two years before Hitler came to power, and helped form a core of support that grew into a full-blown Palestinian branch by 1933. A year later, Ludwig Buchhalter, a teacher at the Templar school in Jerusalem, was active in getting the German consul removed from office for having a Jewish wife, arguing “a person who has relations with Jewish circles cannot be loyal to German interests…” The Templar colony of Sarona, established in 1871 just north of the Arab city of Jaffa, preceded the first Jewish settlement in what is now Tel Aviv and pioneered the export of Jaffa oranges. Now a thriving, upscale neighborhood, Sarona has a museum tracing the history of the German settlement, which includes a room devoted to the Nazi period, but also photos and memorabilia of the early German colonists, their lovely houses, and their fertile farms.

The Templar colony of Sarona, established in 1871 just north of the Arab city of Jaffa, preceded the first Jewish settlement in what is now Tel Aviv and pioneered the export of Jaffa oranges. Now a thriving, upscale neighborhood, Sarona has a museum tracing the history of the German settlement, which includes a room devoted to the Nazi period, but also photos and memorabilia of the early German colonists, their lovely houses, and their fertile farms. In the middle of a sparsely populated and largely barren land, laboring under deficient rule, hundreds of German settlers characterized by great energy, resourcefulness, religious fervor and a variety of professional backgrounds, established a garden city unlike any that existed in the country until then. Outside the Haifa city walls, a boulevard sprang up stretching from the foot of the hills to the sea. It was lined with gardens and homes, remarkable for their beauty.

In the middle of a sparsely populated and largely barren land, laboring under deficient rule, hundreds of German settlers characterized by great energy, resourcefulness, religious fervor and a variety of professional backgrounds, established a garden city unlike any that existed in the country until then. Outside the Haifa city walls, a boulevard sprang up stretching from the foot of the hills to the sea. It was lined with gardens and homes, remarkable for their beauty. Israel and Germany are now allies, Haifa is celebrated as a model of multicultural coexistence, and those markers in the heart of the old port provide a nice history to match its current image: once largely barren and sparsely populated, Haifa was settled by industrious Germans who founded a unique garden city, planted vineyards and olive groves, created new industries, and built a power station and a regional transport system. In 1902 Theodor Herzl’s utopian novel, Altneuland, envisioned this European outpost as the economic center of a future land of Israel, and it soon became a magnet for Jewish settlement. Eventually global politics forced the Germans to leave, but they were paid proper compensation and Haifa today is a lovely, cosmopolitan center, a perfect blend of European civilization and Middle Eastern charm. The Arab population remains relatively sparse numerically, but continues to thrive, a vibrant community with popular nightclubs, restaurants, and a rich arts scene.

Israel and Germany are now allies, Haifa is celebrated as a model of multicultural coexistence, and those markers in the heart of the old port provide a nice history to match its current image: once largely barren and sparsely populated, Haifa was settled by industrious Germans who founded a unique garden city, planted vineyards and olive groves, created new industries, and built a power station and a regional transport system. In 1902 Theodor Herzl’s utopian novel, Altneuland, envisioned this European outpost as the economic center of a future land of Israel, and it soon became a magnet for Jewish settlement. Eventually global politics forced the Germans to leave, but they were paid proper compensation and Haifa today is a lovely, cosmopolitan center, a perfect blend of European civilization and Middle Eastern charm. The Arab population remains relatively sparse numerically, but continues to thrive, a vibrant community with popular nightclubs, restaurants, and a rich arts scene.