This is a parable about history, which is constantly reimagined to fit an evolving present.

In Palestinian memory, Haifa holds a central place as the beautiful coastal city from which thousands of families were exiled in 1948. The precise numbers vary depending on one’s source, but roughly 95 percent of the city’s 60-70,000 Muslim and Christian residents fled or were forced from their homes, expecting to return when the fighting ended. Instead, they were barred from reentering what was now the state of Israel, and the survivors and their descendants have been forced to make new lives as best they can in the West Ba nk, in Jordan, in refugee camps, and in a global diaspora. Some have famously kept the keys to the houses they or their grandparents left – the key has become a symbol of Palestinian return; some tell stories of visiting Haifa in later years, knocking on the doors of their houses and asking the Jewish owners if they could walk through the rooms, see if their family pictures were still on the walls, their rugs still on the floors; others have never set foot in Israel and talk longingly of visiting the places they heard of from their parents or grand-parents.

nk, in Jordan, in refugee camps, and in a global diaspora. Some have famously kept the keys to the houses they or their grandparents left – the key has become a symbol of Palestinian return; some tell stories of visiting Haifa in later years, knocking on the doors of their houses and asking the Jewish owners if they could walk through the rooms, see if their family pictures were still on the walls, their rugs still on the floors; others have never set foot in Israel and talk longingly of visiting the places they heard of from their parents or grand-parents.

At the Jenin Freedom Theater, the set designer told me: “My family is from Haifa, but I have seen the ocean only in Australia.” Different people have different narratives, different hopes, different dreams and nightmares, but all Palestinians agree that the Haifans should have the right to return to Haifa, even if not to a particular house; that the Israelis should acknowledge the theft of their homes and land; and that some form of reparation should be paid for the properties that were expropriated, appropriated, stolen, settled…

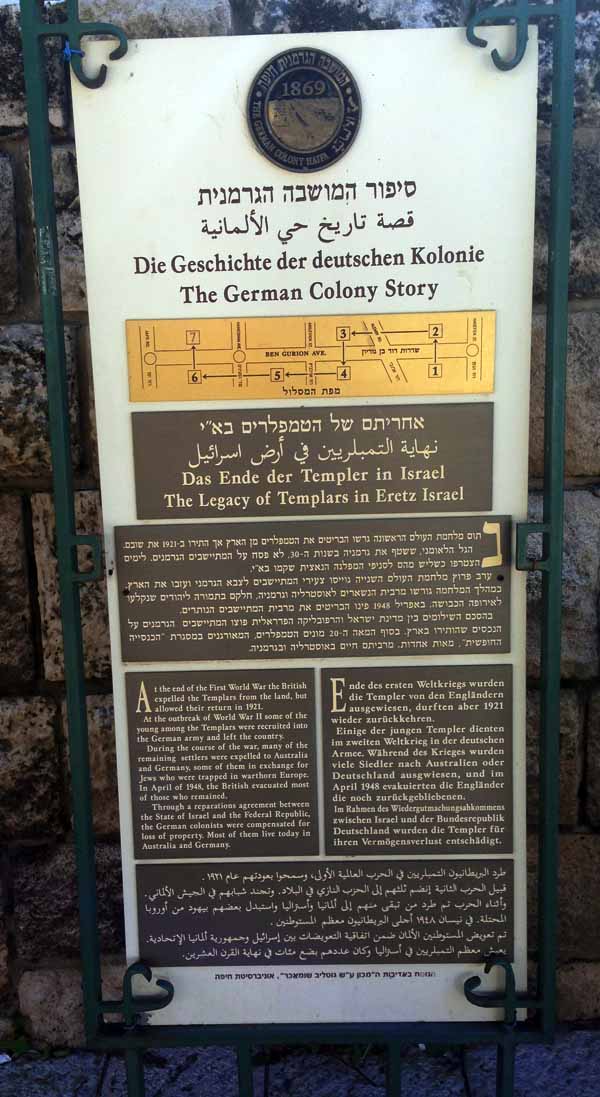

This Palestinian narrative is familiar to anyone who knows anything about the birth of the Israeli state – including Israelis who tell it quite differently, as a narrative of liberation and homecoming, of Arab treachery and flight, and of empty homes justifiably used to settle survivors of the Nazi holocaust. Which is why I was startled by an informational sign on Ben Gurion Avenue in Haifa telling “Die Geschichte der deutschen Kolonie/The German Colony Story,” and in particular about the Templars, a German Protestant group that settled there in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Which is why I was startled by an informational sign on Ben Gurion Avenue in Haifa telling “Die Geschichte der deutschen Kolonie/The German Colony Story,” and in particular about the Templars, a German Protestant group that settled there in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

The sign tells the Templars’ story in Hebrew, German, English, and Arabic, and I was struck by two details: First, it describes young members of the Haifa colony “being recruited into the German army” in World War II and others “expelled to Australia and Germany, some of them in exchange for Jews who were trapped in wartorn Europe.” Second, “through a reparations agreement between the State of Israel and the Federal Republic, the German colonists were compensated for their loss of property.”

That second detail caught me completely off-guard: of all the people who left Haifa in the 1940s – voluntarily and not – and had their property expropriated, the only ones compensated for their loss were Germans who in many case supported and fought for the Third Reich. It isn’t even a secret; it’s explained on a tourist marker in four languages, including Arabic – which remains a standard language for local signage.1

I had recently been traveling on the West Bank, so was particularly attuned to the issue of expropriation without compensation, and only later was struck by the weirdness of detail number one: the descriptions of the local Germans as “being recruited,” suggesting it was not their own idea to go home and fight for the Nazis; the lack of any reference to Nazis; and the mention of Jews who “were trapped” (in passive voice, with no one doing the trapping) in “wartorn Europe” – which could presumably mean anyplace from Leningrad to London, though these particular Jews were trapped in the German concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen.2

A little research establishes that the Templars were closely connected to the National Socialists (Nazis) and their role was far from passive. In Nazis in the Holy Land 1933-1948, Heidemarie Wawrzyn writes that with only two exceptions “the entire NS leadership in Palestine was recruited from the Temple Society.” 3  Karl Ruff, an architect born to Templar parents in Haifa in 1904, made contact with the German Nazis in 1931, two years before Hitler came to power, and helped form a core of support that grew into a full-blown Palestinian branch by 1933. A year later, Ludwig Buchhalter, a teacher at the Templar school in Jerusalem, was active in getting the German consul removed from office for having a Jewish wife, arguing “a person who has relations with Jewish circles cannot be loyal to German interests…”4 There are numerous reports of joint Nazi-Templar events, including marches in uniform through Jerusalem carrying swastika flags. Some historians try to downplay this by noting that only 20-30 percent of Templars became members of the NS, but that is at least double the highest rate of Nazi party membership in Germany.

Karl Ruff, an architect born to Templar parents in Haifa in 1904, made contact with the German Nazis in 1931, two years before Hitler came to power, and helped form a core of support that grew into a full-blown Palestinian branch by 1933. A year later, Ludwig Buchhalter, a teacher at the Templar school in Jerusalem, was active in getting the German consul removed from office for having a Jewish wife, arguing “a person who has relations with Jewish circles cannot be loyal to German interests…”4 There are numerous reports of joint Nazi-Templar events, including marches in uniform through Jerusalem carrying swastika flags. Some historians try to downplay this by noting that only 20-30 percent of Templars became members of the NS, but that is at least double the highest rate of Nazi party membership in Germany.

Exploring this story, I was increasingly puzzled by the euphemistic wording of that sign — in Israel, of all places — and the idea that Israel compensated a substantially Nazi population for lost property in a city famous for the mass seizure of homes and refusal to even discuss compensation.

The official logic of the compensation was that it was a relatively minor detail in the agreement for much larger monetary reparations being paid by Germany to Israel. That larger project was ferociously opposed by many people – not only Germans hesitant to pay but also Israelis irate at the idea of taking money from Germany and non-Israeli Jews irate at the idea of Israel accepting money in the name of world Jewry. Nonetheless a reparations agreement was signed in 1952 and included a side deal to compensate the Templars, though that part remained a touchy subject and only in 1965 did Israel agree to pay them $14,400,000. The final agreement was signed in Sydney, the Australian government having labored assiduously on behalf of the Germans who had been resettled there.5

Obviously, the Arab exiles from Haifa were in a very different situation: they had no government making a major reparations deal to which they could be a footnote; there were far more of them, meaning any compensation agreement would put Israel on the hook for far more money; and they had no major Western power on the level of Australia or Germany backing their claim. (There is a report of one Palestinian-American, Khalil Totah, appealing to the US government to help him get compensation for his seized lands, but I have not been able to confirm the details and in any case it led nowhere.)6

More to the point, history is written in the present: the Arab exiles are still regarded by Israeli officialdom as the enemy, and remembering them as legitimate residents of Haifa would make problems both for a government that regards their claims as a continuing threat and for all the people now living in their houses. By contrast, it is easy to understand why many current residents would like to think of Haifa as a city that was always European.

There has always been a deep cultural affinity between Ashkenazi Jews and their fellow Europeans, and before the Nazi period a particular affinity for German culture. Ashkenazi was the medieval Hebrew word for “German,” and Theodor Herzl, the father of modern Zionism, famously proposed German as the national language of Israel. 7  The Templar colony of Sarona, established in 1871 just north of the Arab city of Jaffa, preceded the first Jewish settlement in what is now Tel Aviv and pioneered the export of Jaffa oranges. Now a thriving, upscale neighborhood, Sarona has a museum tracing the history of the German settlement, which includes a room devoted to the Nazi period, but also photos and memorabilia of the early German colonists, their lovely houses, and their fertile farms.

The Templar colony of Sarona, established in 1871 just north of the Arab city of Jaffa, preceded the first Jewish settlement in what is now Tel Aviv and pioneered the export of Jaffa oranges. Now a thriving, upscale neighborhood, Sarona has a museum tracing the history of the German settlement, which includes a room devoted to the Nazi period, but also photos and memorabilia of the early German colonists, their lovely houses, and their fertile farms.

Searching for more information on the Haifa story, I found another historical marker in “The German Colony Story,” which – again in all four languages – presents “The Contribution of the Templar’s Generation of Founders” in terms that strikingly mimic the Zionist settler narrative:

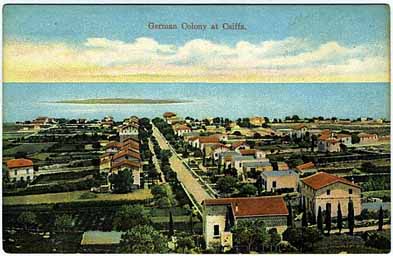

In the middle of a sparsely populated and largely barren land, laboring under deficient rule, hundreds of German settlers characterized by great energy, resourcefulness, religious fervor and a variety of professional backgrounds, established a garden city unlike any that existed in the country until then. Outside the Haifa city walls, a boulevard sprang up stretching from the foot of the hills to the sea. It was lined with gardens and homes, remarkable for their beauty.

In the middle of a sparsely populated and largely barren land, laboring under deficient rule, hundreds of German settlers characterized by great energy, resourcefulness, religious fervor and a variety of professional backgrounds, established a garden city unlike any that existed in the country until then. Outside the Haifa city walls, a boulevard sprang up stretching from the foot of the hills to the sea. It was lined with gardens and homes, remarkable for their beauty.

In 1869 Haifa still trailed Akko (Acre) as a regional port, and the Templars made key contributions to the city’s development, bringing modern machinery and agricultural techniques. Nonetheless, they were never more than a tiny fraction of the local population: by the mid-1880s Haifa was home to about 300 Germans and 6,000 Arabs – variously called “Syrians” or “natives” in contemporary reports – including a substantial class of “wealthy merchants or large landed proprietors,” notable for their fluency in French or Italian and their Parisian furniture and fashions (albeit wearing the fez rather than European hats).8 Which is to say the Germans helped establish Haifa as a large and beautiful “garden city,” but that city was overwhelmingly populated by Arab/Palestinians, who built and owned many of the lovely homes and maintained much of the commercial life.

By the turn of the twentieth century Haifa’s population had expanded to 20,000, now including about a thousand Jews, mostly from Morocco and Algeria. It became a major site of European Jewish immigration after World War I, and by the mid-1940s slightly over half the city’s 128,000 residents were Jews. The rest were still mostly Arab/Palestinians — and would shortly be gone. By the end of the fighting in 1948 the total population had shrunk by a quarter, and 96 percent were Jewish.9

Today, Haifa’s population is about 80 percent Jewish and 11 percent Arab/Palestinian,10 which, depending on one’s perspective, can be framed as pleasantly diverse or the enduring result of ethnic cleansing. And that brings me back to those German Colony historical markers.

Israel and Germany are now allies, Haifa is celebrated as a model of multicultural coexistence, and those markers in the heart of the old port provide a nice history to match its current image: once largely barren and sparsely populated, Haifa was settled by industrious Germans who founded a unique garden city, planted vineyards and olive groves, created new industries, and built a power station and a regional transport system. In 1902 Theodor Herzl’s utopian novel, Altneuland, envisioned this European outpost as the economic center of a future land of Israel, and it soon became a magnet for Jewish settlement. Eventually global politics forced the Germans to leave, but they were paid proper compensation and Haifa today is a lovely, cosmopolitan center, a perfect blend of European civilization and Middle Eastern charm. The Arab population remains relatively sparse numerically, but continues to thrive, a vibrant community with popular nightclubs, restaurants, and a rich arts scene.

Israel and Germany are now allies, Haifa is celebrated as a model of multicultural coexistence, and those markers in the heart of the old port provide a nice history to match its current image: once largely barren and sparsely populated, Haifa was settled by industrious Germans who founded a unique garden city, planted vineyards and olive groves, created new industries, and built a power station and a regional transport system. In 1902 Theodor Herzl’s utopian novel, Altneuland, envisioned this European outpost as the economic center of a future land of Israel, and it soon became a magnet for Jewish settlement. Eventually global politics forced the Germans to leave, but they were paid proper compensation and Haifa today is a lovely, cosmopolitan center, a perfect blend of European civilization and Middle Eastern charm. The Arab population remains relatively sparse numerically, but continues to thrive, a vibrant community with popular nightclubs, restaurants, and a rich arts scene.

It is a pleasant history and reasonably accurate, as long as one sticks to a particular perspective, is careful about one’s language, and ignores unpleasant details.

- Israel is officially a bilingual country, with both Arabic and Hebrew recognized as state languages, but the choice of where Arabic is actually used in official signage could be the subject of an illuminating monograph.

- From Bergen-Belsen to Freedom : The Story of the Exchange of Jewish inmates of Bergen-Belsen with German Templars from Palestine, Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1986.

- Wawrzyn, Nazis in the Holy Land 1933-1948, Walter de Gruyter, 2013, p8

- David Kroyanker, “Swastikas Over Jerusalem,” Haaretz, 6 Nov 2008, https://www.haaretz.com/1.5055818

- https://www.jta.org/1965/09/14/archive/israel-agrees-to-pay-14400000-to-templars-german-christians

- https://electronicintifada.net/content/when-israel-compensated-germans-land-palestine/12512

- Herzl initially regarded Hebrew as a purely ceremonial language, while Yiddish was considered low-class.

- Laurence Oliphant, Haifa: Or, Life in Modern Palestine, Harper & brothers, 1886, 114.

- According to http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/history-and-overview-of-haifa, in 1944 Haifa had 66,000 Jews, 35,940 Muslims, 26,570 Christians, and 3,000 Baha’is; by the end of 1948, the total population was 97,544. Other sources give somewhat different figures, and a UN special report from 1946 shows the population of the entire Haifa district, which covered some 800 square kilometers, as 53% Arab, 47% Jewish.

- http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/shnaton/templ_shnaton_e.html?num_tab=st02_17&CYear=2017 (The remaining nine percent is a mix of Druze, Baha’i, and immigrants from various places.)

Dear Elijah Wald, your are confusing the nineteenth-century German TEMPLER with the twelfth-century Knights TEMPLAR. You need to change the spelling of Templar to Templer.

I am by no means an expert on the Knights Templar or Templer… but my post is about the historical markers in Haifa, and they use the Templer spelling in German and the Templar spelling in English.

The spelling “Templars” on the sign in your photograph is an egregious error, one of countless such mistakes on signposts in Israel. The nineteenth-century German TEMPLER are called “Templers” in English as well (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Templers_(Pietist_sect)). I know of no instance when the German TEMPLER called themselves TEMPLARS in English. If they did, they would be confusing themselves with the twelfth-century French Knights Templar. Do you have a document in which the nineteenth-century German TEMPLER used the English spelling of TEMPLAR for themselves? If not, for your own reputation as a scholar, I suggest once more that you correct this egregious error in your text.