I’m writing this post in Villers-Cotterêts, a small town about an hour outside Paris on the road to Laon. Like most tourists I came here because of Alexandre Dumas, France’s most famous writer, thanks to The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo, and dozens of other books. The walk from the center to the hotel where I’m staying led past the royal palace that inspired young Alexandre with dreams of derring-do, then down a wide and grassy lane bordered with towering trees to narrower path along an ancient, moss-covered stone wall. It felt like Dumas scenery, except on the other side of the wall was a modern low-income housing estate.

I’m writing this post in Villers-Cotterêts, a small town about an hour outside Paris on the road to Laon. Like most tourists I came here because of Alexandre Dumas, France’s most famous writer, thanks to The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo, and dozens of other books. The walk from the center to the hotel where I’m staying led past the royal palace that inspired young Alexandre with dreams of derring-do, then down a wide and grassy lane bordered with towering trees to narrower path along an ancient, moss-covered stone wall. It felt like Dumas scenery, except on the other side of the wall was a modern low-income housing estate. The streets and buildings in it are named for places and characters in Dumas’s novels, the people are the mix typical of modern France: some look like native Picards, some look West African, some wear Muslim headscarves.

The streets and buildings in it are named for places and characters in Dumas’s novels, the people are the mix typical of modern France: some look like native Picards, some look West African, some wear Muslim headscarves.

The connection between that mix and Dumas is what brought me here. I’ve been reading his novel Georges, published in 1843, about a heroic young man who is, in the terms of the time, a Mulatto (mulâtre), of mixed  European and African ancestry. He is from the Island of Mauritius and the action involves his romance with a lady from the island’s ruling class of French plantation owners. It’s an interesting book in a lot of ways, and one is Dumas’s insistence that the prejudice Georges faces from the wealthy French planters is a quirk of the colonial slave system. At the governor’s ball, his lady love is pleased to see him seated between two recently-arrived English ladies, since “she knew that the prejudice which pursued Georges in his native land possessed no influence on the minds of foreigners, and that it required a long residence in the island to cause an inhabitant of Europe to adopt it.”

European and African ancestry. He is from the Island of Mauritius and the action involves his romance with a lady from the island’s ruling class of French plantation owners. It’s an interesting book in a lot of ways, and one is Dumas’s insistence that the prejudice Georges faces from the wealthy French planters is a quirk of the colonial slave system. At the governor’s ball, his lady love is pleased to see him seated between two recently-arrived English ladies, since “she knew that the prejudice which pursued Georges in his native land possessed no influence on the minds of foreigners, and that it required a long residence in the island to cause an inhabitant of Europe to adopt it.”

I was struck by the claim that nineteenth-century Europeans had no race prejudice until they acquired it in the colonies, and would likely have dismissed this passage as naive if Dumas had been a white European—but it is harder to discount the observation coming from someone who had experienced the situation firsthand. Dumas’s mother was the daughter of a prosperous French innkeeper here in Villers-Cotterêts; his father was born a slave in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti).

This is a complicated story, with plenty of contradictions. Dumas occasionally described himself as Mulatto, but more often was cagey and at times misleading. He always referred with great pride to his father, a general in the French army and hero of the Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, but tended to gloss over the details of his father’s youth and wrote in his memoirs that his father was known to the Austrians as “the Black Devil,” and owed “his brown complexion…to the mix of Indian and Caucasian races.” (That is “Caucasian” as in from the Caucasus, and a print in the Dumas museum here shows Dumas himself in traditional Caucasian garb.)

This is a complicated story, with plenty of contradictions. Dumas occasionally described himself as Mulatto, but more often was cagey and at times misleading. He always referred with great pride to his father, a general in the French army and hero of the Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, but tended to gloss over the details of his father’s youth and wrote in his memoirs that his father was known to the Austrians as “the Black Devil,” and owed “his brown complexion…to the mix of Indian and Caucasian races.” (That is “Caucasian” as in from the Caucasus, and a print in the Dumas museum here shows Dumas himself in traditional Caucasian garb.)

As to his father, Thomas-Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie, that story is crazy and far too long to tell here, but to give an example: Thomas-Alexandre’s father was a French aristocrat and slave owner in Saint-Domingue, who fell on hard times and paid his way back to France by selling off his slaves, including his own children—except that the  sales contract for Thomas-Alexandre included a clause allowing his father to buy him back within five years. His father exercised the clause, brought him to France as his legitimate son, sent him to the best schools, and raised him as a French aristocrat. His siblings were never heard from again.

sales contract for Thomas-Alexandre included a clause allowing his father to buy him back within five years. His father exercised the clause, brought him to France as his legitimate son, sent him to the best schools, and raised him as a French aristocrat. His siblings were never heard from again.

Thomas-Alexandre changed his name when he entered the army, choosing the surname of his African-born mother, Marie-Cessette Dumas. One of the pleasures of the museum is its multiple portraits of General Dumas, all showing him in heroic situations and none in any way concealing or downplaying his African ancestry. Notably, none of the documents preserved from his military and civilian life make any mention of his race.

The general’s biography is a complicated and interesting story, well told in Tom Reiss’s The Black Count, and it brought me to Villers-Cotterêts because one of the things I’m exploring in my current project is shifting views of nationality and immigration. I was curious to see who is living here today, how the town recalls Dumas, and if people here connect his ancestry with the increasingly heterogeneous ancestral mix of modern France.

The answer turns out to be exquisitely complicated, and it’s going to take more than this visit to make any sense of it. On the one hand the town has a grand statue of Alexandre Dumas on the main square, and a Dumas museum with rooms dedicated to the general, the novelist, and Alexandre Dumas, fils (junior), who was likewise a famous writer. The stone plaque on the house where General Dumas died notes his African ancestry and his birth in Haiti, and the street in front of it has been the site of an annual celebration on May 10, the anniversary of France’s passage of a law abolishing slavery.

The answer turns out to be exquisitely complicated, and it’s going to take more than this visit to make any sense of it. On the one hand the town has a grand statue of Alexandre Dumas on the main square, and a Dumas museum with rooms dedicated to the general, the novelist, and Alexandre Dumas, fils (junior), who was likewise a famous writer. The stone plaque on the house where General Dumas died notes his African ancestry and his birth in Haiti, and the street in front of it has been the site of an annual celebration on May 10, the anniversary of France’s passage of a law abolishing slavery.

On the other hand, since 2014 the town has elected its mayor from the Front National, the far-right, anti-immigrant party, and the first FN mayor quickly made national news by denouncing the annual celebration of abolition as a display of permanent “auto-culpabilisation,” intended to make French people feel guilty and hence  sympathetic to newcomers from its ex-colonies, and declaring that the town government would no longer take part. All the news stories about this incident noted the irony of anti-immigrant activists standing under the statue of Alexandre Dumas and lamenting the demise of an ethnically homogeneous France.

sympathetic to newcomers from its ex-colonies, and declaring that the town government would no longer take part. All the news stories about this incident noted the irony of anti-immigrant activists standing under the statue of Alexandre Dumas and lamenting the demise of an ethnically homogeneous France.

The town’s population is clearly changing, and some previous residents are clearly upset. Picardy is a famously poor region, and it’s easy to stir up anger against newcomers for taking the few existing jobs. But the obvious newcomers—the people clearly of African ancestry or speaking to one another in Maghrebi Arabic—are going about their lives here, and I saw about as much social mixing as I’m used to seeing in Boston or Philadelphia, and less apparent residential segregation. At the fire station, the three uniformed firefighters sitting outside were a woman who looked French, a man who looked West African, and a man who could have been from anywhere on the shores of the Mediterranean.

Obviously this is a very cursory view and I don’t have any idea what’s going on here. But it was interesting to sit at a table in the Brasserie Alexandre Dumas, looking across the square at the large building that used to be the inn where Dumas’s parents met… and to think that a marriage between the daughter of the Brasserie’s owners and a Haitian immigrant army officer would almost certainly be more controversial here now than it was in 1792… and also a lot more likely.

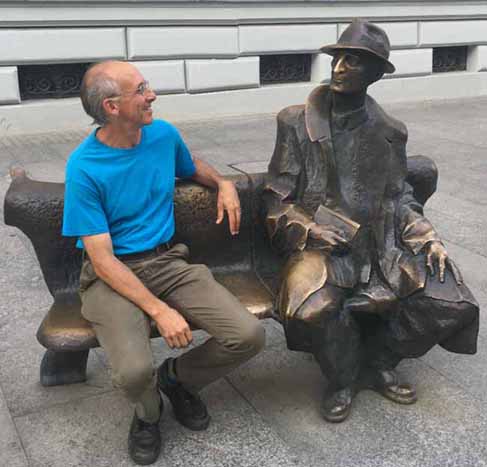

Julian Tuwim. Tuwim is a major figure in Polish literature, a poet, songwriter, and author whose songs and children’s poems are still widely known and performed, but I came across him because of one piece that – not accidentally – was left out of the official five-volume edition of his collected works.

Julian Tuwim. Tuwim is a major figure in Polish literature, a poet, songwriter, and author whose songs and children’s poems are still widely known and performed, but I came across him because of one piece that – not accidentally – was left out of the official five-volume edition of his collected works. “I am a Pole because that’s how I like it. This is my completely private affair which I have no intention of explaining, clarifying, demonstrating or justifying to anyone. I do not divide Poles into ‘pure’ or ‘not pure,’ but leave that to the pure racists, to native and not native Hitlerites. I divide Poles, just as I do Jews and other peoples, into wise and stupid, polite and nasty, intelligent and dull, interesting and boring, injured and injuring, gentlemen and not gentlemen…”

“I am a Pole because that’s how I like it. This is my completely private affair which I have no intention of explaining, clarifying, demonstrating or justifying to anyone. I do not divide Poles into ‘pure’ or ‘not pure,’ but leave that to the pure racists, to native and not native Hitlerites. I divide Poles, just as I do Jews and other peoples, into wise and stupid, polite and nasty, intelligent and dull, interesting and boring, injured and injuring, gentlemen and not gentlemen…” But some of the complications and messiness feel very familiar to me. As those of you who follow my

But some of the complications and messiness feel very familiar to me. As those of you who follow my  Meanwhile, my mother grew up thoroughly Viennese, daughter of two physicians, one of whom was also a concert-quality pianist, immersed in Mozart, Goethe, the earthy Viennese street dialect, and the certainty that she was at the cultural center of the universe. Her childhood foods weren’t latkes and gefilte fish; they were schnitzel, Kaiserschmarrn, and pastries slathered in whipped cream. When the Nazis labeled her a Jew, that changed the course of her life but didn’t change how she thought about herself. She felt rejected by Vienna and often referred to herself not as Viennese but as European, but her views remained thoroughly Viennese, and socialist, and atheist.

Meanwhile, my mother grew up thoroughly Viennese, daughter of two physicians, one of whom was also a concert-quality pianist, immersed in Mozart, Goethe, the earthy Viennese street dialect, and the certainty that she was at the cultural center of the universe. Her childhood foods weren’t latkes and gefilte fish; they were schnitzel, Kaiserschmarrn, and pastries slathered in whipped cream. When the Nazis labeled her a Jew, that changed the course of her life but didn’t change how she thought about herself. She felt rejected by Vienna and often referred to herself not as Viennese but as European, but her views remained thoroughly Viennese, and socialist, and atheist.