April 20, 2018:

April 20, 2018:

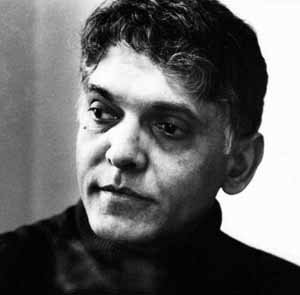

As I watch tens of thousands of Palestinians mass along the militarized zone separating Gaza from Israel, I keep thinking of my friend Eqbal Ahmad. Edward Said described Eqbal as “a man of enormous personal charisma, incorruptible ideals, unfailing generosity and sympathy towards others” — to all of which I can testify — as well as “perhaps the shrewdest and most original anti-imperialist analyst of the post-war world.”1

Though Eqbal was Pakistani, he had been a leading fighter in the Algerian rebellion against France, and the story I’m thinking of took place in 1968. The PLO had just surfaced as a military force and Eqbal was asked to keynote a meeting in the US for an audience of Arab students and activists excited at the prospect of an armed confrontation with the state of Israel. Eqbal spoke as a hardened revolutionary fighter, but not in the way his listeners expected:

After seeing what I saw in Algeria, I couldn’t romanticize armed struggle. The costs to the people of Algeria were very high. OK, they agreed to pay the cost, but it was high. Also, I knew what many people would not recognize even today, which is that the Algerians lost the war militarily, but won it politically. They were successful in isolating France morally. So the primary task of revolutionary struggle is to achieve the moral isolation of the adversary in his own eyes and in the eyes of the world.

I argued that a successful armed struggle proceeds to out-administer the adversary and not out-fight him. And that the task of out-administration was a task of out-legitimizing the enemy. Finally, I argued that this out-administration occurs when you identify the primary contradiction of your adversary and expose that contradiction…. Israel’s fundamental contradiction was that it was founded as a symbol of the suffering of humanity… at the expense of another people who were innocent of guilt. It’s this contradiction that you have to bring out. And you don’t bring it out by armed struggle. In fact, you suppress this contradiction by armed struggle. The Israeli Zionist organizations continue to portray the Jews as victims of Arab violence….

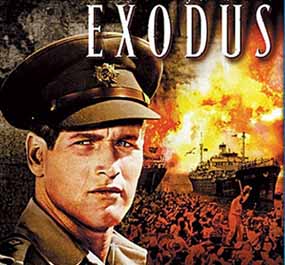

I said, “This is a moment to fit ships in Cyprus, fit boats in Lebanon and say, ‘We’re not going to destroy Israel. That is not our intent. We just want to go home.’ Reverse the symbols of Exodus. See if the Israelis are in a mood to sink some ships. They probably will. Let them do so. Some of us will die. Let us die….” 2

Said, who met Eqbal at that event, was impressed, arranged for Eqbal to make this proposal to the leaders of the PLO and forever recalled it as a missed opportunity. Maybe now, fifty years later, some version of this plan is coming to fruition.

I encourage everyone to check out Eqbal’s writing and speeches on other sites, in books, and on video. Meanwhile, here are a few personal stories:

I’m pretty sure I first met Eqbal in Woods Hole, when he came to talk  about his arrest and upcoming trial as a member of the Harrisburg 7, one of the famous conspiracy trials of the Vietnam War era. His fellow defendants were all Catholic clergy, including Phillip Berrigan, and Eqbal often told how his mother called him when she heard the news, saying: “I can understand you being against the Vietnam war. I can even understand you being arrested for this. But what are you doing being arrested with a group of priests and nuns?!”

about his arrest and upcoming trial as a member of the Harrisburg 7, one of the famous conspiracy trials of the Vietnam War era. His fellow defendants were all Catholic clergy, including Phillip Berrigan, and Eqbal often told how his mother called him when she heard the news, saying: “I can understand you being against the Vietnam war. I can even understand you being arrested for this. But what are you doing being arrested with a group of priests and nuns?!”

After that meeting, Eqbal and his wife Julie were fairly frequent visitors, along with their baby daughter Dora. But the evening I remember best he came alone, fresh off a plane from Europe. The in-flight movie had been The Man Would Be King, and Eqbal was bubbling with enthusiasm: “It was wonderful, a great, old-fashioned action movie — fascist, of course, but wonderful!”

There was wine with dinner, and Eqbal had a few glasses and soon  was telling stories of his youth — that was the only time I heard him talk about seeing his father killed when he was a small boy, hiding behind his father’s legs as the killers attacked, and about fighting in Kashmir. My parents eventually drifted off to bed, but I stayed up, sixteen years old and enthralled. He talked about his student days in Paris, meeting young revolutionaries from around the world. He was particularly struck by the Algerian students who were going home to fight with the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) against French colonialism. He decided he had to get involved, went to Tunis, where he had been given an address on a back street, knocked, and the door was answered by a slim black man who spoke French with a Caribbean accent — Frantz Fanon. The stories went on and on and I remember very little beyond the pleasure of sitting late into the night, listening…

was telling stories of his youth — that was the only time I heard him talk about seeing his father killed when he was a small boy, hiding behind his father’s legs as the killers attacked, and about fighting in Kashmir. My parents eventually drifted off to bed, but I stayed up, sixteen years old and enthralled. He talked about his student days in Paris, meeting young revolutionaries from around the world. He was particularly struck by the Algerian students who were going home to fight with the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) against French colonialism. He decided he had to get involved, went to Tunis, where he had been given an address on a back street, knocked, and the door was answered by a slim black man who spoke French with a Caribbean accent — Frantz Fanon. The stories went on and on and I remember very little beyond the pleasure of sitting late into the night, listening…

…and then there was his food. Eqbal was an astonishing cook — my understanding is that he was arrested with the Catholic leftists because they had gathered for one of his famous meals — and he appreciated my appreciation of his talents. I remember one evening at his apartment on the edge of Harlem when he invited me to dinner and spent the whole evening whispering apologies because a dear friend had arrived in town unexpectedly and was an observant Hindu, so the planned feast had to be sidelined for a vegetarian substitute — still delicious, and I was mostly there for the company, but Eqbal was inconsolable.

There are other stories, but at the moment I keep coming back to that image of Exodus. Partly because I watched the movie in preparation for my trip to Israel/Palestine and recently wrote about the inescapable parallels between Jewish immigrants fighting to enter Palestine and current Palestinians facing Israeli troops at the Gaza fence. Partly because the proliferating images of blonde, blue-eyed Ahed Tamimi as an image of Palestinian resistance recall the choice of Paul Newman to represent the archetypal Israeli fighter. And partly because I remember Eqbal’s enthusiasm for The Man Who Would Be King, and now realize his delight in a good action film was not an apolitical quirk, but on the contrary was integral to his sense of how popular images could be harnessed and redirected to effect change.

There are other stories, but at the moment I keep coming back to that image of Exodus. Partly because I watched the movie in preparation for my trip to Israel/Palestine and recently wrote about the inescapable parallels between Jewish immigrants fighting to enter Palestine and current Palestinians facing Israeli troops at the Gaza fence. Partly because the proliferating images of blonde, blue-eyed Ahed Tamimi as an image of Palestinian resistance recall the choice of Paul Newman to represent the archetypal Israeli fighter. And partly because I remember Eqbal’s enthusiasm for The Man Who Would Be King, and now realize his delight in a good action film was not an apolitical quirk, but on the contrary was integral to his sense of how popular images could be harnessed and redirected to effect change.

I saw Eqbal more rarely in later years. He founded a university in Pakistan and was there much of the time, while I was touring as a musician and writing for the Boston Globe, so one way and another our paths didn’t cross. Our last meeting was at his retirement from Hampshire College, where he had taught for some years. Edward Said and Howard Zinn were there, among many others, and I spoke briefly about Eqbal’s cooking. At the party afterwards he asked me to come to Pakistan and work with him, and I’ll always wonder if he was serious about that, and how my life might have been different if he was and I’d gone.

I saw Eqbal more rarely in later years. He founded a university in Pakistan and was there much of the time, while I was touring as a musician and writing for the Boston Globe, so one way and another our paths didn’t cross. Our last meeting was at his retirement from Hampshire College, where he had taught for some years. Edward Said and Howard Zinn were there, among many others, and I spoke briefly about Eqbal’s cooking. At the party afterwards he asked me to come to Pakistan and work with him, and I’ll always wonder if he was serious about that, and how my life might have been different if he was and I’d gone.

- https://www.ravimagazine.com/eqbal-ahmad-a-true-struggle-a-true-man-by-edward-said/

- Eqbal Ahmad, Confronting Empire: Interviews with David Barsamian, South End Press, 2000, pp29-30.