Most people who oppose building a wall on the US-Mexico border think it is unnecessary, harmful to wildlife, and sends a terrible, xenophobic message about what the United States has become. All of which is true, but also beside the point—which is that it will not have much effect on migration or drug trafficking, but will make Americans less aware and more frightened of the world outside.

I didn’t understand that until I spent a month traveling in Israel and the West Bank. I had heard about the wall there, both from supporters of the Israeli government who credit it with ending terrorist bombings and from supporters of the Palestinians who see it as an instrument for grabbing Palestinian land, dividing Palestinian farmers from their fields, making life difficult for Palestinians who need to cross into Israel, and reminding Palestinians that they are trapped and isolated.

I didn’t understand that until I spent a month traveling in Israel and the West Bank. I had heard about the wall there, both from supporters of the Israeli government who credit it with ending terrorist bombings and from supporters of the Palestinians who see it as an instrument for grabbing Palestinian land, dividing Palestinian farmers from their fields, making life difficult for Palestinians who need to cross into Israel, and reminding Palestinians that they are trapped and isolated.

Indeed, I had heard so much about the wall as a hardship and barrier that I was startled when I got to the West Bank and found young men constantly telling stories of climbing over it—to visit friends and family, find jobs, or just go to a party or a concert. Many of them laughed and talked about it like a teenage rite of passage. Not all had made the trip themselves, but all had friends who had, and some had done it multiple times. “It just costs twenty dollars,” one told me. “You pay a guy, and he puts a ladder up on this side and throws a rope to climb down the other side.” Returning is no problem, because there are no controls in the other direction.

Of course, the wall does keep most Palestinians from crossing easily: families, older people, women, children—anyone who doesn’t want to climb a wall and take a chance on being arrested, who just wants to go shopping or take their kids to the beach or commute to work. And, of course, it’s a problem for anyone carrying luggage or goods, any drivers, ambulances, buses. The only people for whom it’s not a real problem are young, adventurous guys…

…which is to say, the only people for whom it’s not a problem are the most likely soldiers, fighters, or troublemakers.

The ease of wall-crossing is not just popular hearsay. Estimates of how many Palestinians enter Israel without going through official checkpoints vary, but all are impressively high—an LA Times story cites the Israeli state comptroller’s guess that “more than 50,000 Palestinian laborers… work in Israel illegally on a daily basis.” (It adds that along with climbing over the wall, many use drainage ditches to get under it or find unfinished or damaged sections.) 1 So much for the wall’s function as a “security fence”—the official Israeli term, and the function most Israeli Jews seem genuinely to think it serves.

1 So much for the wall’s function as a “security fence”—the official Israeli term, and the function most Israeli Jews seem genuinely to think it serves.

I want to underline the genuine belief of Jewish Israelis—including those who describe themselves as liberal and sympathetic to the Palestinians—that the wall is protecting them from terrorist attacks. Even a lot of people who think the wall is harmful and counterproductive in the long term believe this. Excepting an exceptional few who have spent time on the West Bank—something most Israeli Jews believe is terribly dangerous—none I met had heard of young men crossing illegally by the thousands, or met Palestinians who talked about their adventures making that trip. Since Israeli Jews tend to be very knowledgeable about their country’s history and politics, and to think a lot about how they might possibly, eventually come to some kind of stable situation regarding the Palestinians, this at first surprised me. But then it occurred to me that I had not understood why the wall is there.

My revelation came on a bus from Ramallah to Bethlehem: leaving one city and entering the other, the wall was a towering cement barrier, two stories high. But out in the countryside it gave way to a much less imposing fence of razor wire punctuated with cameras  and motion sensors. Given all the stories of Palestinian climbers, I would not be surprised if these less imposing stretches are actually a more effective barrier—but the towering concrete wall is far more impressive, and it struck me that its massive ugliness is no accident. Its size and weight are a constant reminder to Israeli Jews of the horrors lurking on the other side, the enemies so fearsome that mere wire cannot keep them out. It is theater; theater of fear.

and motion sensors. Given all the stories of Palestinian climbers, I would not be surprised if these less imposing stretches are actually a more effective barrier—but the towering concrete wall is far more impressive, and it struck me that its massive ugliness is no accident. Its size and weight are a constant reminder to Israeli Jews of the horrors lurking on the other side, the enemies so fearsome that mere wire cannot keep them out. It is theater; theater of fear.

It is also a theater curtain, making the stage invisible to the audience. The media carry stories every day of confrontations, raids, attacks, and killings in the West Bank, and most Israeli Jews see only that news and the wall—so it is easy to think of the wall as protecting them from what is on the news, rather than from busy markets, crowded streets, children playing, people going to and from work, and all the normal bustle of normal Palestinian life.

This is not just a Middle Eastern story. Europe and the United States are being swept by a wave of what is broadly mischaracterized as “populism,” but more accurately is politics of fear. Leaders who have nothing positive to offer the mass of voters are relying on paranoia—deflecting worries about declining incomes and a deteriorating planet towards threats from the less fortunate, the foreign, the different. The standard name for this tactic is “divide and conquer,”  and what better way to divide than with a towering wall?

and what better way to divide than with a towering wall?

Opponents of the US-Mexico wall sometimes point out that it is less popular with voters who actually live near the border than with those further away, as if that was odd or ironic—but in fact, it’s normal. People in border towns are constantly interacting with people across the border, so know that they are people, not monsters. But suppose, instead of seeing people on the other side, one just sees a towering wall and terrifying news stories of the mayhem it hides?

Moving back and forth between Israel and the West Bank, it was astonishing how little Israeli Jews knew about daily life on the other side of the wall—I’ve written about some of that in previous posts, but the short version is that although I made no secret of being Jewish I met lots of nice people, made friends, and would strongly recommend that anyone interested in understanding the situation spend some time there. (And I keep specifying “Israeli Jews” because none of this is news to Israeli Muslims and Christians, many of whom cross to the West Bank regularly to shop, visit, or attend university.)

We live in a world of airplanes, drones, rockets, and mass communication. Walls do not protect anybody from serious threats, but they do prevent normal daily interactions—which is to say their function is not to protect us or make us feel safer; it is to increase ignorance and make us more frightened.

Yes, walls built by powerful countries make life somewhat more difficult for people trapped on the other side, but it is a mistake for citizens of those powerful countries who oppose the walls to focus only on the harm they do to others. Building a wall on the US-Mexico border will not actually have much effect on Mexicans or Central Americans, nor is it intended to. It is not a wall around Mexico—it is a wall around the United States. It is not primarily intended to keep “them” out; it is primarily intended to keep “us” ignorant and frightened.

That is the real terrorist threat: not the few fanatics who might potentially hurt some of us, but the powerful people on our side of the walls who want to control us all with a politics of fear.

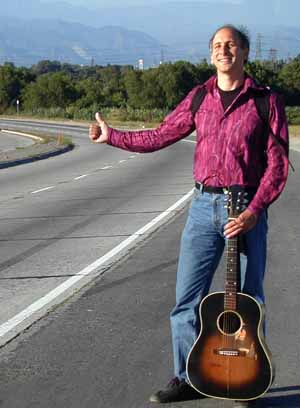

That was the original idea that drew people to travel as a caravan, and it remains the idea for the people involved. They set off this month because this is the best season to travel through Mexico, after the heat of summer and before the cold and rains of winter.

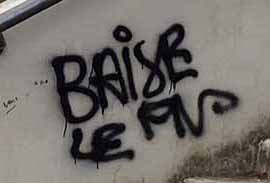

That was the original idea that drew people to travel as a caravan, and it remains the idea for the people involved. They set off this month because this is the best season to travel through Mexico, after the heat of summer and before the cold and rains of winter. I’m writing this post in Villers-Cotterêts, a small town about an hour outside Paris on the road to Laon. Like most tourists I came here because of Alexandre Dumas, France’s most famous writer, thanks to The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo, and dozens of other books. The walk from the center to the hotel where I’m staying led past the royal palace that inspired young Alexandre with dreams of derring-do, then down a wide and grassy lane bordered with towering trees to narrower path along an ancient, moss-covered stone wall. It felt like Dumas scenery, except on the other side of the wall was a modern low-income housing estate.

I’m writing this post in Villers-Cotterêts, a small town about an hour outside Paris on the road to Laon. Like most tourists I came here because of Alexandre Dumas, France’s most famous writer, thanks to The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo, and dozens of other books. The walk from the center to the hotel where I’m staying led past the royal palace that inspired young Alexandre with dreams of derring-do, then down a wide and grassy lane bordered with towering trees to narrower path along an ancient, moss-covered stone wall. It felt like Dumas scenery, except on the other side of the wall was a modern low-income housing estate. The streets and buildings in it are named for places and characters in Dumas’s novels, the people are the mix typical of modern France: some look like native Picards, some look West African, some wear Muslim headscarves.

The streets and buildings in it are named for places and characters in Dumas’s novels, the people are the mix typical of modern France: some look like native Picards, some look West African, some wear Muslim headscarves. European and African ancestry. He is from the Island of Mauritius and the action involves his romance with a lady from the island’s ruling class of French plantation owners. It’s an interesting book in a lot of ways, and one is Dumas’s insistence that the prejudice Georges faces from the wealthy French planters is a quirk of the colonial slave system. At the governor’s ball, his lady love is pleased to see him seated between two recently-arrived English ladies, since “she knew that the prejudice which pursued Georges in his native land possessed no influence on the minds of foreigners, and that it required a long residence in the island to cause an inhabitant of Europe to adopt it.”

European and African ancestry. He is from the Island of Mauritius and the action involves his romance with a lady from the island’s ruling class of French plantation owners. It’s an interesting book in a lot of ways, and one is Dumas’s insistence that the prejudice Georges faces from the wealthy French planters is a quirk of the colonial slave system. At the governor’s ball, his lady love is pleased to see him seated between two recently-arrived English ladies, since “she knew that the prejudice which pursued Georges in his native land possessed no influence on the minds of foreigners, and that it required a long residence in the island to cause an inhabitant of Europe to adopt it.” This is a complicated story, with plenty of contradictions. Dumas occasionally described himself as Mulatto, but more often was cagey and at times misleading. He always referred with great pride to his father, a general in the French army and hero of the Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, but tended to gloss over the details of his father’s youth and wrote in his memoirs that his father was known to the Austrians as “the Black Devil,” and owed “his brown complexion…to the mix of Indian and Caucasian races.” (That is “Caucasian” as in from the Caucasus, and a print in the Dumas museum here shows Dumas himself in traditional Caucasian garb.)

This is a complicated story, with plenty of contradictions. Dumas occasionally described himself as Mulatto, but more often was cagey and at times misleading. He always referred with great pride to his father, a general in the French army and hero of the Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, but tended to gloss over the details of his father’s youth and wrote in his memoirs that his father was known to the Austrians as “the Black Devil,” and owed “his brown complexion…to the mix of Indian and Caucasian races.” (That is “Caucasian” as in from the Caucasus, and a print in the Dumas museum here shows Dumas himself in traditional Caucasian garb.) sales contract for Thomas-Alexandre included a clause allowing his father to buy him back within five years. His father exercised the clause, brought him to France as his legitimate son, sent him to the best schools, and raised him as a French aristocrat. His siblings were never heard from again.

sales contract for Thomas-Alexandre included a clause allowing his father to buy him back within five years. His father exercised the clause, brought him to France as his legitimate son, sent him to the best schools, and raised him as a French aristocrat. His siblings were never heard from again. The answer turns out to be exquisitely complicated, and it’s going to take more than this visit to make any sense of it. On the one hand the town has a grand statue of Alexandre Dumas on the main square, and a Dumas museum with rooms dedicated to the general, the novelist, and Alexandre Dumas, fils (junior), who was likewise a famous writer. The stone plaque on the house where General Dumas died notes his African ancestry and his birth in Haiti, and the street in front of it has been the site of an annual celebration on May 10, the anniversary of France’s passage of a law abolishing slavery.

The answer turns out to be exquisitely complicated, and it’s going to take more than this visit to make any sense of it. On the one hand the town has a grand statue of Alexandre Dumas on the main square, and a Dumas museum with rooms dedicated to the general, the novelist, and Alexandre Dumas, fils (junior), who was likewise a famous writer. The stone plaque on the house where General Dumas died notes his African ancestry and his birth in Haiti, and the street in front of it has been the site of an annual celebration on May 10, the anniversary of France’s passage of a law abolishing slavery. sympathetic to newcomers from its ex-colonies, and declaring that the town government would no longer take part. All the news stories about this incident noted the irony of anti-immigrant activists standing under the statue of Alexandre Dumas and lamenting the demise of an ethnically homogeneous France.

sympathetic to newcomers from its ex-colonies, and declaring that the town government would no longer take part. All the news stories about this incident noted the irony of anti-immigrant activists standing under the statue of Alexandre Dumas and lamenting the demise of an ethnically homogeneous France.

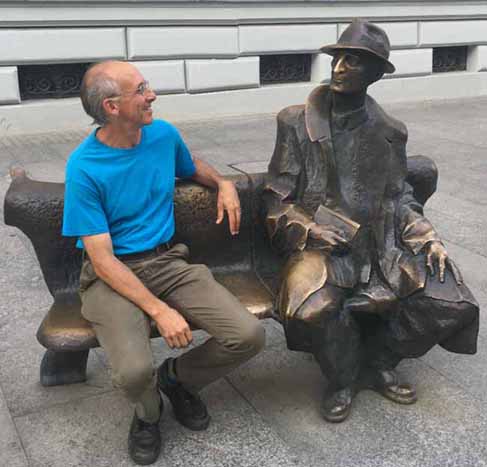

Julian Tuwim. Tuwim is a major figure in Polish literature, a poet, songwriter, and author whose songs and children’s poems are still widely known and performed, but I came across him because of one piece that – not accidentally – was left out of the official five-volume edition of his collected works.

Julian Tuwim. Tuwim is a major figure in Polish literature, a poet, songwriter, and author whose songs and children’s poems are still widely known and performed, but I came across him because of one piece that – not accidentally – was left out of the official five-volume edition of his collected works. “I am a Pole because that’s how I like it. This is my completely private affair which I have no intention of explaining, clarifying, demonstrating or justifying to anyone. I do not divide Poles into ‘pure’ or ‘not pure,’ but leave that to the pure racists, to native and not native Hitlerites. I divide Poles, just as I do Jews and other peoples, into wise and stupid, polite and nasty, intelligent and dull, interesting and boring, injured and injuring, gentlemen and not gentlemen…”

“I am a Pole because that’s how I like it. This is my completely private affair which I have no intention of explaining, clarifying, demonstrating or justifying to anyone. I do not divide Poles into ‘pure’ or ‘not pure,’ but leave that to the pure racists, to native and not native Hitlerites. I divide Poles, just as I do Jews and other peoples, into wise and stupid, polite and nasty, intelligent and dull, interesting and boring, injured and injuring, gentlemen and not gentlemen…” But some of the complications and messiness feel very familiar to me. As those of you who follow my

But some of the complications and messiness feel very familiar to me. As those of you who follow my  Meanwhile, my mother grew up thoroughly Viennese, daughter of two physicians, one of whom was also a concert-quality pianist, immersed in Mozart, Goethe, the earthy Viennese street dialect, and the certainty that she was at the cultural center of the universe. Her childhood foods weren’t latkes and gefilte fish; they were schnitzel, Kaiserschmarrn, and pastries slathered in whipped cream. When the Nazis labeled her a Jew, that changed the course of her life but didn’t change how she thought about herself. She felt rejected by Vienna and often referred to herself not as Viennese but as European, but her views remained thoroughly Viennese, and socialist, and atheist.

Meanwhile, my mother grew up thoroughly Viennese, daughter of two physicians, one of whom was also a concert-quality pianist, immersed in Mozart, Goethe, the earthy Viennese street dialect, and the certainty that she was at the cultural center of the universe. Her childhood foods weren’t latkes and gefilte fish; they were schnitzel, Kaiserschmarrn, and pastries slathered in whipped cream. When the Nazis labeled her a Jew, that changed the course of her life but didn’t change how she thought about herself. She felt rejected by Vienna and often referred to herself not as Viennese but as European, but her views remained thoroughly Viennese, and socialist, and atheist.

996 other Viennese Jews, on November 29, 1941. I wasn’t sure why I wanted to go there, but now I know – it was a powerful experience to be where I know a particular family member was killed, on a particular day.

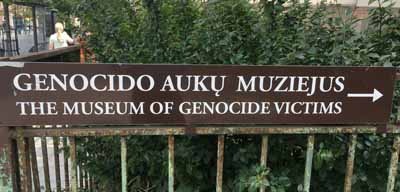

996 other Viennese Jews, on November 29, 1941. I wasn’t sure why I wanted to go there, but now I know – it was a powerful experience to be where I know a particular family member was killed, on a particular day. …the use of the word “genocide,” and specifically the use of Jewish deaths in service of the narrative of non-Jewish suffering is striking. For example, there is a large panel showing the numbers of Lithuanians killed by the Soviets and Nazis: First the roughly 75,000 deaths during fifty years of Soviet occupation, from 1940 to 1990 — 20-25,000 “prisoners who died”; 28,000 “died in deportation”; and 21,500 “Partisans and their supporters killed.” Then the number killed during the four years of German occupation, between 1941-44: “240,000 killed (including about 200,000 Jews).” That is how they phrase it, with the parenthesis.

…the use of the word “genocide,” and specifically the use of Jewish deaths in service of the narrative of non-Jewish suffering is striking. For example, there is a large panel showing the numbers of Lithuanians killed by the Soviets and Nazis: First the roughly 75,000 deaths during fifty years of Soviet occupation, from 1940 to 1990 — 20-25,000 “prisoners who died”; 28,000 “died in deportation”; and 21,500 “Partisans and their supporters killed.” Then the number killed during the four years of German occupation, between 1941-44: “240,000 killed (including about 200,000 Jews).” That is how they phrase it, with the parenthesis. es and sent them on a forced march in which the weak fell and died, destroying towns and villages in a region where Arabs had treated arriving Jews as friends and neighbors. Shavit frames this as a devastating indictment of Israeli policy — but in 32 pages mentions the name of only one Arab. He begins by telling how named Jews settled in the area and befriended unnamed Arabs; tells of meetings between named Jewish leaders and unnamed Arab leaders; and quotes named Jewish perpetrators about their attacks on unnamed Arab victims. Even when an Arab is finally named, as a victim with his family of the death march, he is never quoted directly—unlike numerous Jewish witnesses—and Shavit’s sympathetic description of the abuses inflicted on his father, mother, cousin, grandmother, and brothers does not include their names. Jews are condemned for committing atrocities, but they are individuals, with names and voices; the Arabs are nameless and voiceless.

es and sent them on a forced march in which the weak fell and died, destroying towns and villages in a region where Arabs had treated arriving Jews as friends and neighbors. Shavit frames this as a devastating indictment of Israeli policy — but in 32 pages mentions the name of only one Arab. He begins by telling how named Jews settled in the area and befriended unnamed Arabs; tells of meetings between named Jewish leaders and unnamed Arab leaders; and quotes named Jewish perpetrators about their attacks on unnamed Arab victims. Even when an Arab is finally named, as a victim with his family of the death march, he is never quoted directly—unlike numerous Jewish witnesses—and Shavit’s sympathetic description of the abuses inflicted on his father, mother, cousin, grandmother, and brothers does not include their names. Jews are condemned for committing atrocities, but they are individuals, with names and voices; the Arabs are nameless and voiceless. I came to Lithuania following Jutta’s story, bringing her picture and the story of how she got stuck in Vienna, the number of the transport that brought her to Kaunas, and the date when the 998 Viennese Jews on that train were chased up the hill at the Ninth Fort, pushed into mass graves, and shot – or in some cases shot, then pushed into mass graves. I wondered if the museum might be interested in having a copy of the photograph of Jutte and her mother, Gustl.

I came to Lithuania following Jutta’s story, bringing her picture and the story of how she got stuck in Vienna, the number of the transport that brought her to Kaunas, and the date when the 998 Viennese Jews on that train were chased up the hill at the Ninth Fort, pushed into mass graves, and shot – or in some cases shot, then pushed into mass graves. I wondered if the museum might be interested in having a copy of the photograph of Jutte and her mother, Gustl. It gives the numbers of Lithuanian Jews killed, and displays personal items – eye glasses, shaving brushes, a pair of child’s shoes – found in the mass graves. It is a touching display. Not one Jew is named.

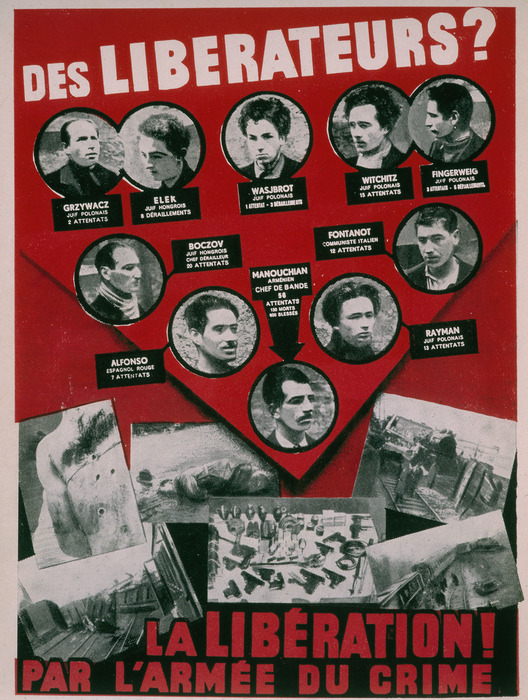

It gives the numbers of Lithuanian Jews killed, and displays personal items – eye glasses, shaving brushes, a pair of child’s shoes – found in the mass graves. It is a touching display. Not one Jew is named. There is a second museum in the fort itself, for those who wish to delve deeper. It was largely funded from abroad, and includes rooms with photographs of individual Jews, their names, their stories. There is a powerful display sponsored by “Les Familles et Amis des Déportés du Convoi 73, Paris (France),” about a transport of 878 French Jews killed here in 1944, including walls of photographs identified by name. There is a room about the Kaunas ghetto, with family pictures, names, and stories from survivors. There is a room about the escape of 64 prisoners who were brought in 1943 to burn the thousands of corpses, naming them and noting that 60 were Jews, along with three Russians and a Pole. There is a room with stories of survivors, saying what happened to them in later years. There is a room about the Japanese consul who in defiance of his government provided six thousand Jews with exit visas. There is a room about “Lithuanians, the Saviours of the Jews,” with stories of Lithuanian Gentiles who hid or helped their Jewish neighbors. And there is a room about Hitler and the genocide of European Jews, with names of 1,344 Jews from various parts of Europe who were killed here, each with their age and home town. Jutta and Gustl were not included – I looked for them, and the omission bothered me. But to continue…

There is a second museum in the fort itself, for those who wish to delve deeper. It was largely funded from abroad, and includes rooms with photographs of individual Jews, their names, their stories. There is a powerful display sponsored by “Les Familles et Amis des Déportés du Convoi 73, Paris (France),” about a transport of 878 French Jews killed here in 1944, including walls of photographs identified by name. There is a room about the Kaunas ghetto, with family pictures, names, and stories from survivors. There is a room about the escape of 64 prisoners who were brought in 1943 to burn the thousands of corpses, naming them and noting that 60 were Jews, along with three Russians and a Pole. There is a room with stories of survivors, saying what happened to them in later years. There is a room about the Japanese consul who in defiance of his government provided six thousand Jews with exit visas. There is a room about “Lithuanians, the Saviours of the Jews,” with stories of Lithuanian Gentiles who hid or helped their Jewish neighbors. And there is a room about Hitler and the genocide of European Jews, with names of 1,344 Jews from various parts of Europe who were killed here, each with their age and home town. Jutta and Gustl were not included – I looked for them, and the omission bothered me. But to continue… At the back of that room is a curtain, and if you go through there is a smaller room with a film showing the testimony of eight Lithuanian soldiers who were sentenced to death by the Soviet government in 1962 for participating in Nazi-organized massacres. One mimes standing at the edge of the mass graves and shooting down into the crowds of people, and explains how he would sell items he picked off the victims to buy a drink afterwards because “when you do such kind of thing you need to wet your whistle.”

At the back of that room is a curtain, and if you go through there is a smaller room with a film showing the testimony of eight Lithuanian soldiers who were sentenced to death by the Soviet government in 1962 for participating in Nazi-organized massacres. One mimes standing at the edge of the mass graves and shooting down into the crowds of people, and explains how he would sell items he picked off the victims to buy a drink afterwards because “when you do such kind of thing you need to wet your whistle.” At the Ninth Fort there are memorial stones placed by the city of Frankfurt in memory of the Jews transported from there to Kaunas; by the families and friends of the Jews transported and killed from France; by the city of Berlin in memory of the thousand Jewish children, women and men transported on Nov 17, 1941 and killed here on Nov 25; by the city of Munich in memory of the thousand Jews transported from there on November 20, 1941, and killed here five days later. There is no stone from Austria or from the city of Vienna to commemorate the transport on November 23 that included my cousins. Like the Lithuanians, the Austrians prefer to recall the Nazi period as their own tragedy, not a Jewish tragedy. They do not deny that Jews were particularly selected for extermination, but they have their own issues, and feel we must remember it was a tough time, and everybody suffered…

At the Ninth Fort there are memorial stones placed by the city of Frankfurt in memory of the Jews transported from there to Kaunas; by the families and friends of the Jews transported and killed from France; by the city of Berlin in memory of the thousand Jewish children, women and men transported on Nov 17, 1941 and killed here on Nov 25; by the city of Munich in memory of the thousand Jews transported from there on November 20, 1941, and killed here five days later. There is no stone from Austria or from the city of Vienna to commemorate the transport on November 23 that included my cousins. Like the Lithuanians, the Austrians prefer to recall the Nazi period as their own tragedy, not a Jewish tragedy. They do not deny that Jews were particularly selected for extermination, but they have their own issues, and feel we must remember it was a tough time, and everybody suffered… one photograph that, if you take the trouble to read the small print on its caption, turns out to show “the exhumation of remains of Soviet prisoners of war.” They aren’t denying there were Russians killed in the Nazi period. If asked, I’m sure they would acknowledge that the Nazis killed millions of Soviet citizens, including some in Lithuania. That’s just not the story this museum is here to tell.

one photograph that, if you take the trouble to read the small print on its caption, turns out to show “the exhumation of remains of Soviet prisoners of war.” They aren’t denying there were Russians killed in the Nazi period. If asked, I’m sure they would acknowledge that the Nazis killed millions of Soviet citizens, including some in Lithuania. That’s just not the story this museum is here to tell. This particular mosque apparently dates from the 18th century, but the community that built it has been in the region since the mid-17th century. They are Tatars, descendants of the Golden Horde that reached Eastern Europe shortly after the death of Genghis Khan. Since I’m traveling here as part of a project on borders and migration, and in particular looking into my own family’s history, when I read about the Tatars I immediately wondered what happened to them during the Nazi occupation.

This particular mosque apparently dates from the 18th century, but the community that built it has been in the region since the mid-17th century. They are Tatars, descendants of the Golden Horde that reached Eastern Europe shortly after the death of Genghis Khan. Since I’m traveling here as part of a project on borders and migration, and in particular looking into my own family’s history, when I read about the Tatars I immediately wondered what happened to them during the Nazi occupation. Robertson also writes that the Tatar Mufti of Poland, Jacob Szynkiewicz, helped protect the Karaite Jews by calling Goebbels to make the case that they were racially Turkic. I haven’t found corroboration of that particular story, but there is plenty of evidence that the Nazis considered the Karaim related to the Tatars both by ancestry and as communities that interacted on a regular basis – and therefore (except in a few notable instances) did not subject them to ghettoization or extermination. As a result, some Jews – meaning Ashkenazim – also managed to survive the holocaust by passing as Jews – meaning Karaim.

Robertson also writes that the Tatar Mufti of Poland, Jacob Szynkiewicz, helped protect the Karaite Jews by calling Goebbels to make the case that they were racially Turkic. I haven’t found corroboration of that particular story, but there is plenty of evidence that the Nazis considered the Karaim related to the Tatars both by ancestry and as communities that interacted on a regular basis – and therefore (except in a few notable instances) did not subject them to ghettoization or extermination. As a result, some Jews – meaning Ashkenazim – also managed to survive the holocaust by passing as Jews – meaning Karaim. tour of the mosque in Kruszyniany was conducted entirely in Polish, so I understood virtually nothing, but I did catch the words, “Charles Bronson…Charles Buchinski.” I assumed the guide was claiming Bronson as a Tatar, so checked and found that yes, indeed, his father was apparently a Tatar from Lithuania, and this touch of Mongolian heritage presumably was what made him so easy to cast as a Native American…

tour of the mosque in Kruszyniany was conducted entirely in Polish, so I understood virtually nothing, but I did catch the words, “Charles Bronson…Charles Buchinski.” I assumed the guide was claiming Bronson as a Tatar, so checked and found that yes, indeed, his father was apparently a Tatar from Lithuania, and this touch of Mongolian heritage presumably was what made him so easy to cast as a Native American… On a more serious note, the Tatars have recently been caught up in the anti-Muslim violence sweeping Europe. A mosque built by Tatars in Gdansk in the 1990s was firebombed in 2013, and in 2014 the historic mosque and cemetery I visited in Krusziniany were defaced with anti-Muslim slogans and a drawing of a pig. Which is ugly, and the ugliness is underlined by a story in the New York Times that quotes local Tatars blaming the violence on the influx of Muslim immigrants, which they see as raising justifiable concern among Poles that is causing friction where none existed before.

On a more serious note, the Tatars have recently been caught up in the anti-Muslim violence sweeping Europe. A mosque built by Tatars in Gdansk in the 1990s was firebombed in 2013, and in 2014 the historic mosque and cemetery I visited in Krusziniany were defaced with anti-Muslim slogans and a drawing of a pig. Which is ugly, and the ugliness is underlined by a story in the New York Times that quotes local Tatars blaming the violence on the influx of Muslim immigrants, which they see as raising justifiable concern among Poles that is causing friction where none existed before. , two of the five synagogues are even still there… but the synagogues are abandoned and boarded up, because the Jews who used to be almost a third of the population are not there anymore, nor are their descendants… and same in Lesko, where 70% of the town used to be Jewish, and now the only remaining synagogue is an art gallery, and much of the art is Christs and Madonnas and saints… and I recently posted a funny story about

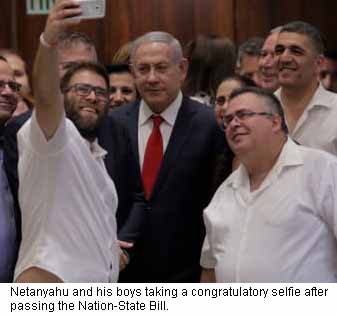

, two of the five synagogues are even still there… but the synagogues are abandoned and boarded up, because the Jews who used to be almost a third of the population are not there anymore, nor are their descendants… and same in Lesko, where 70% of the town used to be Jewish, and now the only remaining synagogue is an art gallery, and much of the art is Christs and Madonnas and saints… and I recently posted a funny story about  Nation-State Bill, which says “the right to national self-determination in Israel is unique to the Jewish people” — which is another way of saying if you are an Arab Israeli, you may live there but it is not your country.

Nation-State Bill, which says “the right to national self-determination in Israel is unique to the Jewish people” — which is another way of saying if you are an Arab Israeli, you may live there but it is not your country.

skansen reflects the multi-cultural nature of rural Galicia in 1900, with sections showing the lifestyles of the Eastern Orthodox Boyks and Lemks, the Catholic (now often called “ethnic”) Poles… and a large wooden synagogue and two “Jewish” houses on the main square.

skansen reflects the multi-cultural nature of rural Galicia in 1900, with sections showing the lifestyles of the Eastern Orthodox Boyks and Lemks, the Catholic (now often called “ethnic”) Poles… and a large wooden synagogue and two “Jewish” houses on the main square. He spoke some English, and enthusiastically showed us around: the bedroom, for example, where he pointed out the curling iron for shaping the men’s peyos and the peculiarity of the marital bed, which could be separated when the Jewish woman had her period or had given birth, hence was “unclean,” and pushed together again after she had bathed in the mikveh. He showed us the special dishes for meat and dairy, and the sabbath dishes. All very strange and exotic…

He spoke some English, and enthusiastically showed us around: the bedroom, for example, where he pointed out the curling iron for shaping the men’s peyos and the peculiarity of the marital bed, which could be separated when the Jewish woman had her period or had given birth, hence was “unclean,” and pushed together again after she had bathed in the mikveh. He showed us the special dishes for meat and dairy, and the sabbath dishes. All very strange and exotic…

nk, in Jordan, in refugee camps, and in a global diaspora. Some have famously kept the keys to the houses they or their grandparents left – the key has become a symbol of Palestinian return; some tell stories of visiting Haifa in later years, knocking on the doors of their houses and asking the Jewish owners if they could walk through the rooms, see if their family pictures were still on the walls, their rugs still on the floors; others have never set foot in Israel and talk longingly of visiting the places they heard of from their parents or grand-parents.

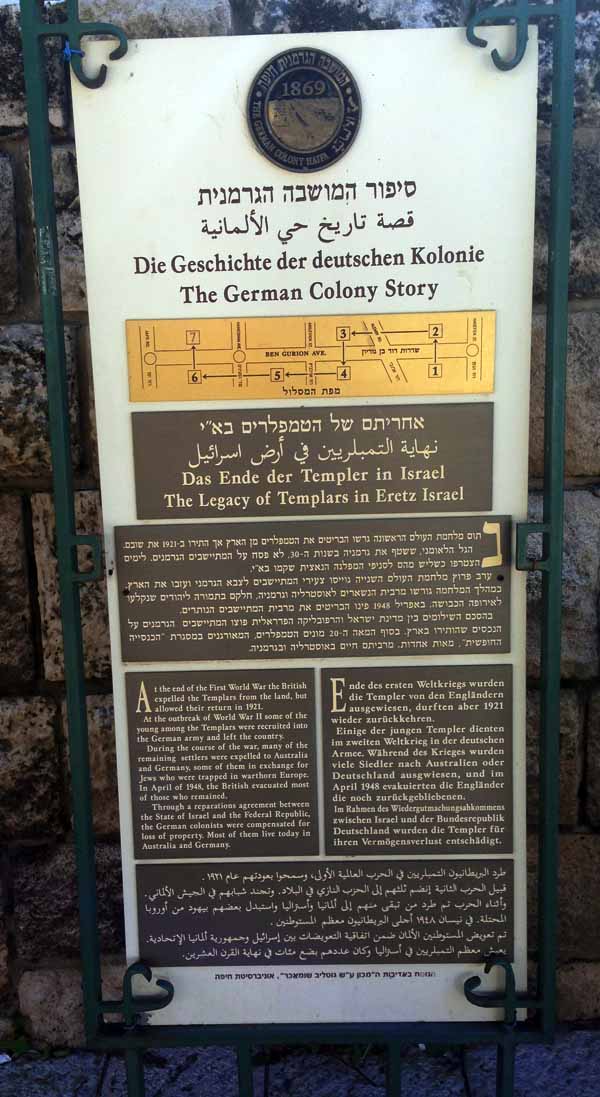

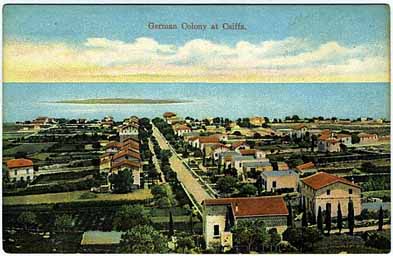

nk, in Jordan, in refugee camps, and in a global diaspora. Some have famously kept the keys to the houses they or their grandparents left – the key has become a symbol of Palestinian return; some tell stories of visiting Haifa in later years, knocking on the doors of their houses and asking the Jewish owners if they could walk through the rooms, see if their family pictures were still on the walls, their rugs still on the floors; others have never set foot in Israel and talk longingly of visiting the places they heard of from their parents or grand-parents. Which is why I was startled by an informational sign on Ben Gurion Avenue in Haifa telling “Die Geschichte der deutschen Kolonie/The German Colony Story,” and in particular about the Templars, a German Protestant group that settled there in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Which is why I was startled by an informational sign on Ben Gurion Avenue in Haifa telling “Die Geschichte der deutschen Kolonie/The German Colony Story,” and in particular about the Templars, a German Protestant group that settled there in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Karl Ruff, an architect born to Templar parents in Haifa in 1904, made contact with the German Nazis in 1931, two years before Hitler came to power, and helped form a core of support that grew into a full-blown Palestinian branch by 1933. A year later, Ludwig Buchhalter, a teacher at the Templar school in Jerusalem, was active in getting the German consul removed from office for having a Jewish wife, arguing “a person who has relations with Jewish circles cannot be loyal to German interests…”

Karl Ruff, an architect born to Templar parents in Haifa in 1904, made contact with the German Nazis in 1931, two years before Hitler came to power, and helped form a core of support that grew into a full-blown Palestinian branch by 1933. A year later, Ludwig Buchhalter, a teacher at the Templar school in Jerusalem, was active in getting the German consul removed from office for having a Jewish wife, arguing “a person who has relations with Jewish circles cannot be loyal to German interests…” The Templar colony of Sarona, established in 1871 just north of the Arab city of Jaffa, preceded the first Jewish settlement in what is now Tel Aviv and pioneered the export of Jaffa oranges. Now a thriving, upscale neighborhood, Sarona has a museum tracing the history of the German settlement, which includes a room devoted to the Nazi period, but also photos and memorabilia of the early German colonists, their lovely houses, and their fertile farms.

The Templar colony of Sarona, established in 1871 just north of the Arab city of Jaffa, preceded the first Jewish settlement in what is now Tel Aviv and pioneered the export of Jaffa oranges. Now a thriving, upscale neighborhood, Sarona has a museum tracing the history of the German settlement, which includes a room devoted to the Nazi period, but also photos and memorabilia of the early German colonists, their lovely houses, and their fertile farms. In the middle of a sparsely populated and largely barren land, laboring under deficient rule, hundreds of German settlers characterized by great energy, resourcefulness, religious fervor and a variety of professional backgrounds, established a garden city unlike any that existed in the country until then. Outside the Haifa city walls, a boulevard sprang up stretching from the foot of the hills to the sea. It was lined with gardens and homes, remarkable for their beauty.

In the middle of a sparsely populated and largely barren land, laboring under deficient rule, hundreds of German settlers characterized by great energy, resourcefulness, religious fervor and a variety of professional backgrounds, established a garden city unlike any that existed in the country until then. Outside the Haifa city walls, a boulevard sprang up stretching from the foot of the hills to the sea. It was lined with gardens and homes, remarkable for their beauty. Israel and Germany are now allies, Haifa is celebrated as a model of multicultural coexistence, and those markers in the heart of the old port provide a nice history to match its current image: once largely barren and sparsely populated, Haifa was settled by industrious Germans who founded a unique garden city, planted vineyards and olive groves, created new industries, and built a power station and a regional transport system. In 1902 Theodor Herzl’s utopian novel, Altneuland, envisioned this European outpost as the economic center of a future land of Israel, and it soon became a magnet for Jewish settlement. Eventually global politics forced the Germans to leave, but they were paid proper compensation and Haifa today is a lovely, cosmopolitan center, a perfect blend of European civilization and Middle Eastern charm. The Arab population remains relatively sparse numerically, but continues to thrive, a vibrant community with popular nightclubs, restaurants, and a rich arts scene.

Israel and Germany are now allies, Haifa is celebrated as a model of multicultural coexistence, and those markers in the heart of the old port provide a nice history to match its current image: once largely barren and sparsely populated, Haifa was settled by industrious Germans who founded a unique garden city, planted vineyards and olive groves, created new industries, and built a power station and a regional transport system. In 1902 Theodor Herzl’s utopian novel, Altneuland, envisioned this European outpost as the economic center of a future land of Israel, and it soon became a magnet for Jewish settlement. Eventually global politics forced the Germans to leave, but they were paid proper compensation and Haifa today is a lovely, cosmopolitan center, a perfect blend of European civilization and Middle Eastern charm. The Arab population remains relatively sparse numerically, but continues to thrive, a vibrant community with popular nightclubs, restaurants, and a rich arts scene. Colonial Exhibition of 1931. The facade of this building, which first housed the Musée des Colonies, is a huge cement bas-relief of scenes from “greater France” — elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers, temples, sailing ships, and toiling or warlike natives of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, set off with mentions of what each area has contributed to the mother country: rice, rubber, cotton, tea…

Colonial Exhibition of 1931. The facade of this building, which first housed the Musée des Colonies, is a huge cement bas-relief of scenes from “greater France” — elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers, temples, sailing ships, and toiling or warlike natives of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, set off with mentions of what each area has contributed to the mother country: rice, rubber, cotton, tea… foreigner highlighted on the timeline is Frédéric Chopin, arriving in 1831 “like numerous intellectual, military, political, and artistic Polish insurgents after the failed revolt against the power of the Czar.”

foreigner highlighted on the timeline is Frédéric Chopin, arriving in 1831 “like numerous intellectual, military, political, and artistic Polish insurgents after the failed revolt against the power of the Czar.” This affair notably split French intellectuals and artists, with Degas (a particularly vicious anti-Semite), Renoir, and Cézanne expressing their distaste for the “foreigners” — so denominated though some Jewish families had been in France for many generations — while Monet and Mary Cassatt lined up on the other side, along with Pissarro, who was Jewish, born in the Danish West Indies, and sometimes bore the brunt of his colleagues’ prejudice.

This affair notably split French intellectuals and artists, with Degas (a particularly vicious anti-Semite), Renoir, and Cézanne expressing their distaste for the “foreigners” — so denominated though some Jewish families had been in France for many generations — while Monet and Mary Cassatt lined up on the other side, along with Pissarro, who was Jewish, born in the Danish West Indies, and sometimes bore the brunt of his colleagues’ prejudice.

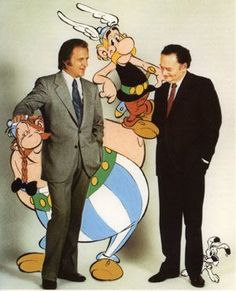

I’m not trying to recap the whole museum — a five-hour visit was not sufficient to explore its range and depth — but a couple more details are worth mentioning. One is the charming irony that the most familiar evocation of an indigenous French heritage, the comic book adventures of Asterix, Obelix, and their fellow Gauls holding out against the Roman Empire, was created by a pair of second-generation immigrants: Alberto Uderzo, whose parents immigrated from Italy shortly before his birth, and René Goscinny, the son of Polish Jews.

I’m not trying to recap the whole museum — a five-hour visit was not sufficient to explore its range and depth — but a couple more details are worth mentioning. One is the charming irony that the most familiar evocation of an indigenous French heritage, the comic book adventures of Asterix, Obelix, and their fellow Gauls holding out against the Roman Empire, was created by a pair of second-generation immigrants: Alberto Uderzo, whose parents immigrated from Italy shortly before his birth, and René Goscinny, the son of Polish Jews. that visitors should be inspired to donate material about their own immigrant families and history in France, among the donations is a baby-foot table (what Americans call foosball and other Anglophones table football) made by the Bonzini family, descendants of Italian immigrants who are one of the main French manufacturers. The Bonzinis originally donated the table for an exhibition called

that visitors should be inspired to donate material about their own immigrant families and history in France, among the donations is a baby-foot table (what Americans call foosball and other Anglophones table football) made by the Bonzini family, descendants of Italian immigrants who are one of the main French manufacturers. The Bonzinis originally donated the table for an exhibition called