(Initialement publié en anglais le 30 octobre 2023)

J’écris normalement en tant qu’Américain d’origine européenne, mais dans les mois qui ont suivi le 7 octobre, j’ai souvent écrit spécifiquement en tant que juif, car je ne peux m’empêcher de réagir en tant que juif à ce qui se passe en Israël/Palestine. J’ai des amis et des cousines là-bas, et cela affecte mes réactions ; et je lis et j’entends des gens discuter sur ce sujet en termes de ce qui s’est passé et pourrait arriver aux « Juifs », c’est-à-dire aux gens comme moi, non seulement en Israël, mais ailleurs.

Ma mère a grandi à Vienne. Elle avait 14 ans en 1938, lorsque l’armée allemande est arrivée et a été accueillie par des défilés. Elle passait les semaines suivantes à faire des courses pour ses parents car il était dangereux pour eux de se retrouver dans la rue. Ils n’étaient pas seulement juifs, mais aussi gens de gauche, et ils ont compris immédiatement qu’ils devraient partir. C’était plus facile de sortir dans les premiers mois, et ils sont venus aux États-Unis. Mon grand-père a aidé d’autres membres de la famille à sortir. Il a essayé d’aider son frère préféré et la cousine préférée de ma mère, mais pour diverses raisons ceci n’ont pas quitté le pays avant qu’il ne soit trop tard. Ils ont été transportés vers l’est dans les wagons à bestiaux et exterminés.

Ma mère a grandi à Vienne. Elle avait 14 ans en 1938, lorsque l’armée allemande est arrivée et a été accueillie par des défilés. Elle passait les semaines suivantes à faire des courses pour ses parents car il était dangereux pour eux de se retrouver dans la rue. Ils n’étaient pas seulement juifs, mais aussi gens de gauche, et ils ont compris immédiatement qu’ils devraient partir. C’était plus facile de sortir dans les premiers mois, et ils sont venus aux États-Unis. Mon grand-père a aidé d’autres membres de la famille à sortir. Il a essayé d’aider son frère préféré et la cousine préférée de ma mère, mais pour diverses raisons ceci n’ont pas quitté le pays avant qu’il ne soit trop tard. Ils ont été transportés vers l’est dans les wagons à bestiaux et exterminés.

Ma mère a vécu cette expérience jusqu’à sa mort à l’âge de 90 ans. Elle s’est toujours considérée comme une réfugiée. Elle a trouvé la sécurité aux États-Unis, mais ne s’y est jamais sentie chez elle. Elle a également découvert qu’aux États-Unis, elle était traitée comme une personne blanche et que d’autres Blancs lui parlaient des Noirs de la même manière que les Autrichiens allemands parlaient des Juifs. Même de nombreux Juifs américains parlaient des Noirs de la même manière que les Autrichiens allemands parlaient des Juifs.

Elle avait vécu l’expérience des nazis et avait constaté que de nombreux Américains blancs se comportaient comme des nazis. Donc plutôt que d’élever ma sœur et moi dans la peur des nazis ou que de nous apprendre à poser la question : « qui nous cacherait si les nazis arrivaient ? » – elle nous a élevés pour ne pas être des nazis. Elle nous a appris à mépriser le militarisme et le racisme, et à défendre les personnes exclues ou opprimées, les immigrés, les réfugiés, les personnes considérées ou traitées comme différentes. Pour elle, ces gens étaient « les Juifs », les gens comme elle, quels qu’ils soient.

Aucune boussole morale n’est parfaite. Il est parfois difficile de déterminer qui sont les « bon gars ». Parfois, il n’y a pas de bons gars. Mais il est toujours possible de choisir de ne pas être nazi – de dire que peu importe à quel point on est poussé, à quel point on peut se sentir désespéré ou en colère, ou à quel point on a peur, il y a des choses qu’on ne fera pas.

Ma mère nous a appris que les bombardements d’Hiroshima et de Nagasaki étaient des atrocités impardonnables, comme l’Holocauste – et que nous devons faire tout notre possible pour empêcher que de telles choses ne se reproduisent. Quand j’ai lu « Abattoir 5 » de Kurt Vonnegut et que je lui ai posé des questions sur l’attentat à la bombe incendiaire contre Dresde, elle a répondu que c’était la même chose : une atrocité visant une population civile. Le fait qu’ils étaient Allemands, dont beaucoup étaient vraisemblablement nazis, n’excusait pas le choix de les éliminer, hommes, femmes et enfants. Assassiner aveuglément des dizaines ou des centaines de milliers de personnes en raison de leur identité ou de leur lieu de résidence, c’était se comporter comme les nazis.

Ma mère n’était pas exceptionnelle. De nombreux réfugiés et survivants de l’Holocauste nazi ont eu des réactions similaires. C’était presque un cliché des écrits israéliens sur la formation de l’État juif et l’expulsion des Palestiniens : le moment où un soldat juif a regardé autour de lui et a réalisé qu’il se comportait désormais comme un nazi et les Palestiniens étaient les Juifs. Certains auteurs ont poussé cette méditation jusqu’à sa conclusion logique (pour moi) et se sont retournés contre le projet d’État sioniste – certains sont partis ; certains ont continué à vivre en Israël/Palestine, mais ont travaillé à façonner un avenir multiethnique et multireligieux, que ce soit dans un État ou deux. D’autres ont tiré une leçon plus douteuse (pour moi), concluant qu’ils faisaient quelque chose d’horrible mais qu’ils n’avaient pas le choix : l’analogie fréquente était que les Juifs ont sauté d’un bâtiment en feu, atterrissant malheureusement sur la tête de quelqu’un d’autre ; ils ont blessé un passant et en ont été désolés, mais l’essentiel était qu’ils ont dû sauter.

Je continue d’entendre de nombreuses personnes faire écho à cette affirmation, selon laquelle les Israéliens font quelque chose de terrible, mais n’ont pas le choix. Mais de plus en plus, j’entends une affirmation différente : que les Palestiniens – ou plus précisément le Hamas – sont les nazis. Je n’ai pas besoin de célébrer ou d’excuser le Hamas pour rejeter cette analogie. Si les nazis avaient été une bande de fanatiques désespérés menant occasionnellement d’horribles attaques contre des civils, on se souviendrait à peine d’eux, car il y a eu des centaines de groupes comme celui-là, partout dans le monde. Ce qui distinguait les nazis n’était pas qu’ils détestaient les Juifs – c’est un cliché de l’histoire juive que nous avons toujours eu des ennemis – mais qu’ils exploitaient la puissance d’un État-nation moderne et de la technologie moderne pour tuer non seulement des centaines ou des milliers de personnes, mais des millions.

Je ne vais pas rejeter une fausse analogie avec les nazis pour en adopter une autre. Le fait que de nombreuses personnes, dans de nombreuses guerres, aient eu des moments où ils ont réalisé qu’ils se comportaient comme des nazis ne signifie pas que ce qu’ils ont fait était comparable. Les nazis ont commis un génocide méthodique qui n’avait jamais été tenté à tel échelle et qui n’a jamais été égalé – ils n’étaient en aucun cas la seule nation à commettre ou à tenter un génocide, mais ils l’ont géré avec une efficacité qui était unique, et en ce sens uniquement horrible.

Mais, en tant que fils de ma mère, je pense à son histoire et je m’en laisse guider. Ma mère s’est opposée inconditionnellement à la peine de mort : elle ne croyait pas que l’État devrait jamais tuer des gens calmement et efficacement, peu importe ce qu’ils avaient fait – et encore moins tuer toute leur famille, leurs enfants. Elle avait particulièrement horreur des États « civilisés » qui tuaient avec l’efficacité moderne : si une nation larguait des bombes sur des gens qui n’avaient pas d’avions, elle s’imaginait toujours sous les bombes, pas dans les avions. Elle pouvait s’imaginer à Dresde ou à Hiroshima ; elle aurait pu s’imaginer dans un kibboutz le 7 octobre, se cachant des assassins, mais elle aurait beaucoup plus facilement pu s’imaginer à Gaza, sous les bombes. Il m’est beaucoup plus facile de m’imaginer à Gaza, sous les bombes. C’est un sort beaucoup plus courant dans notre monde moderne ; Les victimes voient rarement ceux qui les tuent, et les tueurs ne les voient pas non plus.

Il y a quelques années, je suis allé en Pologne, à Przemysl, pour voir d’où venaient ma grand-mère et aussi le père de mon père. Certains amis juifs ne comprenaient pas pourquoi je voulais visiter cet endroit ni comment je pouvais en ressentir de la nostalgie. Ils me disaient : « Les Polonais étaient encore pires que les Allemands ». Ce commentaire m’a paru bizarre, alors ils m’ont envoyé des histoires pornographiques violentes, sur des paysans éventrant des femmes juives avec des faux, ou rassemblant des Juifs dans une synagogue avec des gourdins et y mettant le feu. Ces histoires étaient horribles, mais l’implication était pire : que les paysans qui étaient habitués à abattre des animaux avec des couteaux de boucher et à massacrer les Juifs de la même manière étaient pires que les Allemands civilisés qui achetaient leur viande dans les magasins et envoyaient les Juifs se faire gazer efficacement par millions. Pour moi, c’est ce qui définit le fait d’être « comme les nazis » : des meurtres méthodiques sanctionnés par l’État, utilisant les dernières technologies et anéantissant familles entières sans même avoir à regarder les personnes qu’on tue.

Ceci ne s’agit pas d’un État ou d’un autre. Il s’agit d’avoir le pouvoir de tuer avec efficacité, avec les mains propres, comme la grande majorité des gens ont été tués dans la plupart des guerres de ma vie. Et oui, je pense que c’est encore plus horrible que tuer à l’ancienne, parce qu’il est plus facile de prétendre que vous ne le faites pas, ou que vous préféreriez ne pas le faire – et quand vous pouvez faire semblant de ne pas le faire, vous pouvez en faire bien plus, et désactiver les images, ou les rejeter comme de la propagande, ou déplorer les morts, mais en tant que chiffres, pas en tant que personnes.

Je vois les photos des Israéliens tués le 7 octobre, avec leurs noms et leurs biographies. Les images de Gaza montrent des quartiers entiers détruits, des masses de blessés et de morts – j’entends des chiffres plutôt que des noms : trente mille tués, quarante mille tués. C’est le langage des statistiques, le langage de l’abattoir, du nombre de hamburgers vendus par McDonald’s. La plupart d’entre nous ressentent une horreur plus viscérale face à la mort d’une personne que nous connaissons par son nom et son visage que face à la mort abstraite de dix mille ou cent mille personnes. Mais je m’imagine aussi plus facilement sous les bombes que dans les avions. Et tout ce que je veux, c’est que les bombardements s’arrêtent.

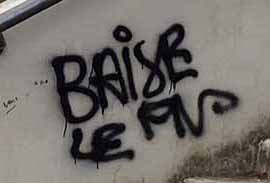

Ce n’est pas la réponse à des problèmes à long terme, ni à des traumatismes et à des haines qui remontent à plusieurs décennies et générations. Mais c’est la réponse vitale et immédiate à ce qui doit être fait maintenant, aujourd’hui. Cessez-le-feu ; arrêtez le massacre. Ensuite, faites tout ce qu’il faut pour réduire la haine, le traumatisme ; faites le long et dur travail de construction, qui est toujours plus difficile et prend plus de temps que de détruire. Mais d’abord, arrêtez. Arrêtez les bombardements. Apportez de la nourriture, de l’eau, du carburant et des fournitures médicales aux personnes coincées et mourantes. Ce n’est pas une réponse à toute l’histoire profonde et douloureuse, ni aux questions infinies sur ce qu’il faut faire ensuite – mais pour l’instant, c’est la seule réponse qui compte.

five months: the region’s only university; the oldest Christian church; a mosque; the zoo; a cultural center; an orphanage; a park — the trees bulldozed — and smaller places: a bakery, a pizzeria…

five months: the region’s only university; the oldest Christian church; a mosque; the zoo; a cultural center; an orphanage; a park — the trees bulldozed — and smaller places: a bakery, a pizzeria… The Post story refers to this as “urbicide,” the destruction of a city, but it is more than that, and does not require an academic term. It is an attempt to destroy memory; to destroy culture; to destroy hope.

The Post story refers to this as “urbicide,” the destruction of a city, but it is more than that, and does not require an academic term. It is an attempt to destroy memory; to destroy culture; to destroy hope. Vienna was not a paradise for Jews; it had a deep history of antisemitism, and my mother had direct memories of the Nazis marching, the books being burnt, the Jews being forced to scrub the streets; but when she took us back there, it was to share the Prater, the Riesenrad, the Stephansplatz, the Brueghels in the national museum, the restaurants where you could order a schnitzel and hear the cook hammering in the kitchen.

Vienna was not a paradise for Jews; it had a deep history of antisemitism, and my mother had direct memories of the Nazis marching, the books being burnt, the Jews being forced to scrub the streets; but when she took us back there, it was to share the Prater, the Riesenrad, the Stephansplatz, the Brueghels in the national museum, the restaurants where you could order a schnitzel and hear the cook hammering in the kitchen.

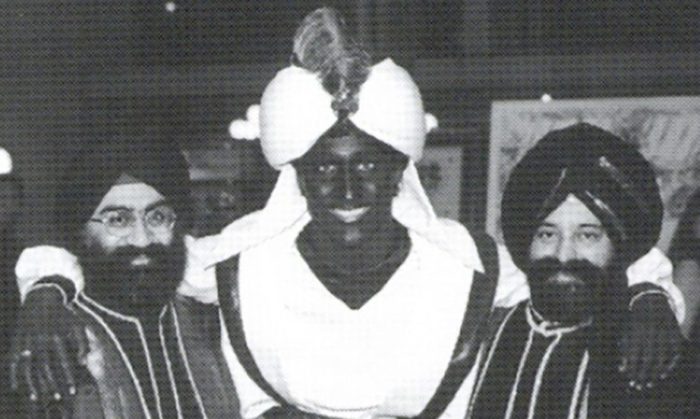

Japanese geishas traditionally whiten their faces with rice powder. If we agree that Perry is white, in color-swatch terms it would seem ridiculous to protest against her wearing white make-up…

Japanese geishas traditionally whiten their faces with rice powder. If we agree that Perry is white, in color-swatch terms it would seem ridiculous to protest against her wearing white make-up…

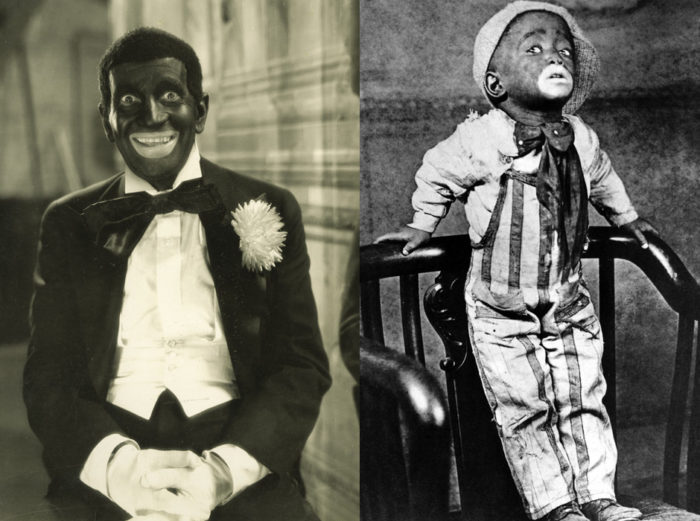

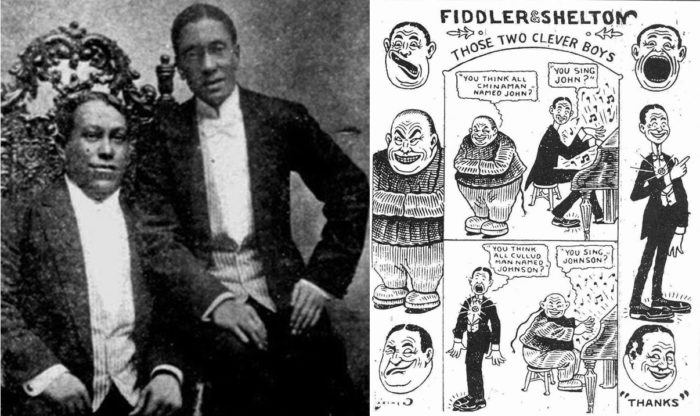

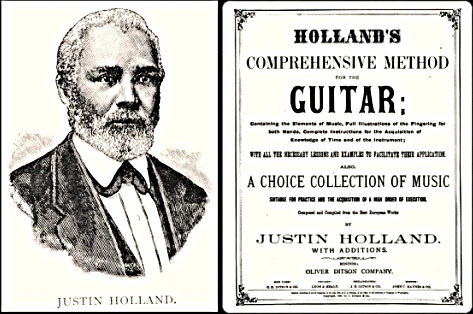

within categories marked as Black culture. There is a great deal of writing on Black artists who performed ragtime, blues, and jazz, but the deep history of African American classical music has had far less study, and likewise the many Black singers and musicians who performed in other styles that were not marked as Black, such as mainstream pop, hillbilly, Hawaiian, Italian, and so forth.

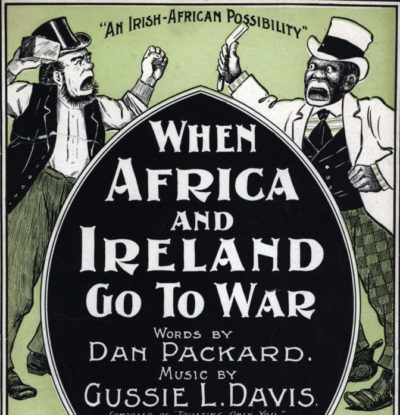

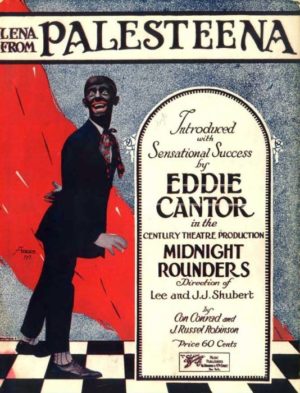

within categories marked as Black culture. There is a great deal of writing on Black artists who performed ragtime, blues, and jazz, but the deep history of African American classical music has had far less study, and likewise the many Black singers and musicians who performed in other styles that were not marked as Black, such as mainstream pop, hillbilly, Hawaiian, Italian, and so forth. Periods of high immigration and intense anti-immigrant agitation come and go, but the bedrock of anti-Black racism remains. The Black ethnic delineators are an interesting byway of US culture, but their history does not in any way mitigate the enduring racism of blackface minstrelsy. On the contrary, the fact that you could perform pretty much any kind of ethnic caricature in blackface underlines the extent to which racism directed at African Americans has served as a more general paradigm.

Periods of high immigration and intense anti-immigrant agitation come and go, but the bedrock of anti-Black racism remains. The Black ethnic delineators are an interesting byway of US culture, but their history does not in any way mitigate the enduring racism of blackface minstrelsy. On the contrary, the fact that you could perform pretty much any kind of ethnic caricature in blackface underlines the extent to which racism directed at African Americans has served as a more general paradigm. I live up the street from a mural of South Philadelphia singers of the 1950s, and aside from the Jewish Eddie Fisher and the Black Chubby Checker, all the others are Italian (though many changed their names to play down their ethnicity, Bobby Ridarelli becoming Bobby Rydell, Jimmy Ercolani becoming Jimmy Darren).

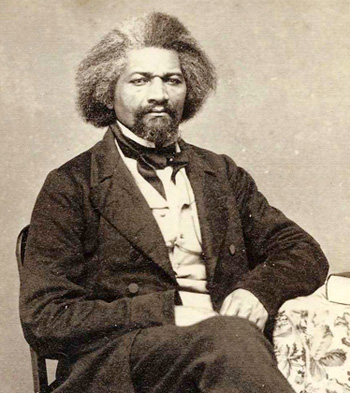

I live up the street from a mural of South Philadelphia singers of the 1950s, and aside from the Jewish Eddie Fisher and the Black Chubby Checker, all the others are Italian (though many changed their names to play down their ethnicity, Bobby Ridarelli becoming Bobby Rydell, Jimmy Ercolani becoming Jimmy Darren). Men, like bees, want elbow room. When the hive is overcrowded, the bees will swarm, and will be likely to take up their abode where they find the best prospect for honey. In matters of this sort, men are very much like bees…. The same mighty forces which have swept to our shores the overflowing populations of Europe; which have reduced the people of Ireland three millions below its normal standard; will operate in a similar manner upon the hungry population of China and other parts of Asia. Home has its charms, and native land has its charms, but hunger, oppression, and destitution, will dissolve these charms and send men in search of new countries and new homes….

Men, like bees, want elbow room. When the hive is overcrowded, the bees will swarm, and will be likely to take up their abode where they find the best prospect for honey. In matters of this sort, men are very much like bees…. The same mighty forces which have swept to our shores the overflowing populations of Europe; which have reduced the people of Ireland three millions below its normal standard; will operate in a similar manner upon the hungry population of China and other parts of Asia. Home has its charms, and native land has its charms, but hunger, oppression, and destitution, will dissolve these charms and send men in search of new countries and new homes…. I spent my second day in Hebron walking around, taking pictures, getting a better sense of where everything was. I went through a couple of full-scale checkpoints with turnstiles and metal detectors, and others with just a couple of soldiers with automatic rifles, and wherever I went they waved me through with a smile, even when I set off the metal detectors — I was asked my nationality a couple of times and once asked for my passport, but just to see I had one, not to open it and check my photo… because I was obviously a tourist and everybody wants more of those.

I spent my second day in Hebron walking around, taking pictures, getting a better sense of where everything was. I went through a couple of full-scale checkpoints with turnstiles and metal detectors, and others with just a couple of soldiers with automatic rifles, and wherever I went they waved me through with a smile, even when I set off the metal detectors — I was asked my nationality a couple of times and once asked for my passport, but just to see I had one, not to open it and check my photo… because I was obviously a tourist and everybody wants more of those. the hills above… it’s weird and fascinating, because these inimical populations are completely intertwined, sometimes on different floors of the same house. And no one was bothering me — some people didn’t return my hellos, but the soldiers were consistently polite and cheerful, and when I asked if I could take their picture they said, “Sure, you can do anything you want…”

the hills above… it’s weird and fascinating, because these inimical populations are completely intertwined, sometimes on different floors of the same house. And no one was bothering me — some people didn’t return my hellos, but the soldiers were consistently polite and cheerful, and when I asked if I could take their picture they said, “Sure, you can do anything you want…” They were very helpful, telling me how things were different in various periods, and we gradually made our way down the hill and back to the street in front of the Ibrahimi Mosque, which I had already walked up and down at least three times. They introduced me to a Palestinian man who runs a souvenir shop there, and while we were chatting the Israeli soldiers who were guarding that end of the street came over from the checkpoint and asked the women who they were and what they were doing. Then the women left to catch their ride back to Tel Aviv, and I had a coffee in the souvenir shop and headed back towards that street in front of the mosque, which was also the street to the hostel where I was staying…

They were very helpful, telling me how things were different in various periods, and we gradually made our way down the hill and back to the street in front of the Ibrahimi Mosque, which I had already walked up and down at least three times. They introduced me to a Palestinian man who runs a souvenir shop there, and while we were chatting the Israeli soldiers who were guarding that end of the street came over from the checkpoint and asked the women who they were and what they were doing. Then the women left to catch their ride back to Tel Aviv, and I had a coffee in the souvenir shop and headed back towards that street in front of the mosque, which was also the street to the hostel where I was staying… they’d seen me with. I said no, and they asked where I was going. I said I was going back to my hostel. They asked, “You are a Jew?” I said yes. They said, “You cannot go here.”

they’d seen me with. I said no, and they asked where I was going. I said I was going back to my hostel. They asked, “You are a Jew?” I said yes. They said, “You cannot go here.” I walked up the dirt road that led behind the mosque, into a thoroughly Arab neighborhood, wandered up dirt roads and down alleys, asked a couple of people for directions, and eventually wound my way down to the other end of the same street in front of the mosque… where another pair of soldiers who hadn’t seen me consorting with elderly Israeli peace observers waved me through with a smile. So that was that. I walked back through the market, bought a handful of almonds and a falafel sandwich with roast eggplant, hot pepper sauce, and pickled vegetables, retrieved my guitar and pack from the hostel, and caught a minibus to Bethlehem.

I walked up the dirt road that led behind the mosque, into a thoroughly Arab neighborhood, wandered up dirt roads and down alleys, asked a couple of people for directions, and eventually wound my way down to the other end of the same street in front of the mosque… where another pair of soldiers who hadn’t seen me consorting with elderly Israeli peace observers waved me through with a smile. So that was that. I walked back through the market, bought a handful of almonds and a falafel sandwich with roast eggplant, hot pepper sauce, and pickled vegetables, retrieved my guitar and pack from the hostel, and caught a minibus to Bethlehem.

I didn’t understand that until I spent a month traveling in Israel and the West Bank. I had heard about the wall there, both from supporters of the Israeli government who credit it with ending terrorist bombings and from supporters of the Palestinians who see it as an instrument for grabbing Palestinian land, dividing Palestinian farmers from their fields, making life difficult for Palestinians who need to cross into Israel, and reminding Palestinians that they are trapped and isolated.

I didn’t understand that until I spent a month traveling in Israel and the West Bank. I had heard about the wall there, both from supporters of the Israeli government who credit it with ending terrorist bombings and from supporters of the Palestinians who see it as an instrument for grabbing Palestinian land, dividing Palestinian farmers from their fields, making life difficult for Palestinians who need to cross into Israel, and reminding Palestinians that they are trapped and isolated.

and motion sensors. Given all the stories of Palestinian climbers, I would not be surprised if these less imposing stretches are actually a more effective barrier—but the towering concrete wall is far more impressive, and it struck me that its massive ugliness is no accident. Its size and weight are a constant reminder to Israeli Jews of the horrors lurking on the other side, the enemies so fearsome that mere wire cannot keep them out. It is theater; theater of fear.

and motion sensors. Given all the stories of Palestinian climbers, I would not be surprised if these less imposing stretches are actually a more effective barrier—but the towering concrete wall is far more impressive, and it struck me that its massive ugliness is no accident. Its size and weight are a constant reminder to Israeli Jews of the horrors lurking on the other side, the enemies so fearsome that mere wire cannot keep them out. It is theater; theater of fear. and what better way to divide than with a towering wall?

and what better way to divide than with a towering wall?

That was the original idea that drew people to travel as a caravan, and it remains the idea for the people involved. They set off this month because this is the best season to travel through Mexico, after the heat of summer and before the cold and rains of winter.

That was the original idea that drew people to travel as a caravan, and it remains the idea for the people involved. They set off this month because this is the best season to travel through Mexico, after the heat of summer and before the cold and rains of winter. I’m writing this post in Villers-Cotterêts, a small town about an hour outside Paris on the road to Laon. Like most tourists I came here because of Alexandre Dumas, France’s most famous writer, thanks to The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo, and dozens of other books. The walk from the center to the hotel where I’m staying led past the royal palace that inspired young Alexandre with dreams of derring-do, then down a wide and grassy lane bordered with towering trees to narrower path along an ancient, moss-covered stone wall. It felt like Dumas scenery, except on the other side of the wall was a modern low-income housing estate.

I’m writing this post in Villers-Cotterêts, a small town about an hour outside Paris on the road to Laon. Like most tourists I came here because of Alexandre Dumas, France’s most famous writer, thanks to The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo, and dozens of other books. The walk from the center to the hotel where I’m staying led past the royal palace that inspired young Alexandre with dreams of derring-do, then down a wide and grassy lane bordered with towering trees to narrower path along an ancient, moss-covered stone wall. It felt like Dumas scenery, except on the other side of the wall was a modern low-income housing estate. The streets and buildings in it are named for places and characters in Dumas’s novels, the people are the mix typical of modern France: some look like native Picards, some look West African, some wear Muslim headscarves.

The streets and buildings in it are named for places and characters in Dumas’s novels, the people are the mix typical of modern France: some look like native Picards, some look West African, some wear Muslim headscarves. European and African ancestry. He is from the Island of Mauritius and the action involves his romance with a lady from the island’s ruling class of French plantation owners. It’s an interesting book in a lot of ways, and one is Dumas’s insistence that the prejudice Georges faces from the wealthy French planters is a quirk of the colonial slave system. At the governor’s ball, his lady love is pleased to see him seated between two recently-arrived English ladies, since “she knew that the prejudice which pursued Georges in his native land possessed no influence on the minds of foreigners, and that it required a long residence in the island to cause an inhabitant of Europe to adopt it.”

European and African ancestry. He is from the Island of Mauritius and the action involves his romance with a lady from the island’s ruling class of French plantation owners. It’s an interesting book in a lot of ways, and one is Dumas’s insistence that the prejudice Georges faces from the wealthy French planters is a quirk of the colonial slave system. At the governor’s ball, his lady love is pleased to see him seated between two recently-arrived English ladies, since “she knew that the prejudice which pursued Georges in his native land possessed no influence on the minds of foreigners, and that it required a long residence in the island to cause an inhabitant of Europe to adopt it.” This is a complicated story, with plenty of contradictions. Dumas occasionally described himself as Mulatto, but more often was cagey and at times misleading. He always referred with great pride to his father, a general in the French army and hero of the Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, but tended to gloss over the details of his father’s youth and wrote in his memoirs that his father was known to the Austrians as “the Black Devil,” and owed “his brown complexion…to the mix of Indian and Caucasian races.” (That is “Caucasian” as in from the Caucasus, and a print in the Dumas museum here shows Dumas himself in traditional Caucasian garb.)

This is a complicated story, with plenty of contradictions. Dumas occasionally described himself as Mulatto, but more often was cagey and at times misleading. He always referred with great pride to his father, a general in the French army and hero of the Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, but tended to gloss over the details of his father’s youth and wrote in his memoirs that his father was known to the Austrians as “the Black Devil,” and owed “his brown complexion…to the mix of Indian and Caucasian races.” (That is “Caucasian” as in from the Caucasus, and a print in the Dumas museum here shows Dumas himself in traditional Caucasian garb.) sales contract for Thomas-Alexandre included a clause allowing his father to buy him back within five years. His father exercised the clause, brought him to France as his legitimate son, sent him to the best schools, and raised him as a French aristocrat. His siblings were never heard from again.

sales contract for Thomas-Alexandre included a clause allowing his father to buy him back within five years. His father exercised the clause, brought him to France as his legitimate son, sent him to the best schools, and raised him as a French aristocrat. His siblings were never heard from again. The answer turns out to be exquisitely complicated, and it’s going to take more than this visit to make any sense of it. On the one hand the town has a grand statue of Alexandre Dumas on the main square, and a Dumas museum with rooms dedicated to the general, the novelist, and Alexandre Dumas, fils (junior), who was likewise a famous writer. The stone plaque on the house where General Dumas died notes his African ancestry and his birth in Haiti, and the street in front of it has been the site of an annual celebration on May 10, the anniversary of France’s passage of a law abolishing slavery.

The answer turns out to be exquisitely complicated, and it’s going to take more than this visit to make any sense of it. On the one hand the town has a grand statue of Alexandre Dumas on the main square, and a Dumas museum with rooms dedicated to the general, the novelist, and Alexandre Dumas, fils (junior), who was likewise a famous writer. The stone plaque on the house where General Dumas died notes his African ancestry and his birth in Haiti, and the street in front of it has been the site of an annual celebration on May 10, the anniversary of France’s passage of a law abolishing slavery. sympathetic to newcomers from its ex-colonies, and declaring that the town government would no longer take part. All the news stories about this incident noted the irony of anti-immigrant activists standing under the statue of Alexandre Dumas and lamenting the demise of an ethnically homogeneous France.

sympathetic to newcomers from its ex-colonies, and declaring that the town government would no longer take part. All the news stories about this incident noted the irony of anti-immigrant activists standing under the statue of Alexandre Dumas and lamenting the demise of an ethnically homogeneous France.

Julian Tuwim. Tuwim is a major figure in Polish literature, a poet, songwriter, and author whose songs and children’s poems are still widely known and performed, but I came across him because of one piece that – not accidentally – was left out of the official five-volume edition of his collected works.

Julian Tuwim. Tuwim is a major figure in Polish literature, a poet, songwriter, and author whose songs and children’s poems are still widely known and performed, but I came across him because of one piece that – not accidentally – was left out of the official five-volume edition of his collected works. “I am a Pole because that’s how I like it. This is my completely private affair which I have no intention of explaining, clarifying, demonstrating or justifying to anyone. I do not divide Poles into ‘pure’ or ‘not pure,’ but leave that to the pure racists, to native and not native Hitlerites. I divide Poles, just as I do Jews and other peoples, into wise and stupid, polite and nasty, intelligent and dull, interesting and boring, injured and injuring, gentlemen and not gentlemen…”

“I am a Pole because that’s how I like it. This is my completely private affair which I have no intention of explaining, clarifying, demonstrating or justifying to anyone. I do not divide Poles into ‘pure’ or ‘not pure,’ but leave that to the pure racists, to native and not native Hitlerites. I divide Poles, just as I do Jews and other peoples, into wise and stupid, polite and nasty, intelligent and dull, interesting and boring, injured and injuring, gentlemen and not gentlemen…” But some of the complications and messiness feel very familiar to me. As those of you who follow my

But some of the complications and messiness feel very familiar to me. As those of you who follow my  Meanwhile, my mother grew up thoroughly Viennese, daughter of two physicians, one of whom was also a concert-quality pianist, immersed in Mozart, Goethe, the earthy Viennese street dialect, and the certainty that she was at the cultural center of the universe. Her childhood foods weren’t latkes and gefilte fish; they were schnitzel, Kaiserschmarrn, and pastries slathered in whipped cream. When the Nazis labeled her a Jew, that changed the course of her life but didn’t change how she thought about herself. She felt rejected by Vienna and often referred to herself not as Viennese but as European, but her views remained thoroughly Viennese, and socialist, and atheist.

Meanwhile, my mother grew up thoroughly Viennese, daughter of two physicians, one of whom was also a concert-quality pianist, immersed in Mozart, Goethe, the earthy Viennese street dialect, and the certainty that she was at the cultural center of the universe. Her childhood foods weren’t latkes and gefilte fish; they were schnitzel, Kaiserschmarrn, and pastries slathered in whipped cream. When the Nazis labeled her a Jew, that changed the course of her life but didn’t change how she thought about herself. She felt rejected by Vienna and often referred to herself not as Viennese but as European, but her views remained thoroughly Viennese, and socialist, and atheist.