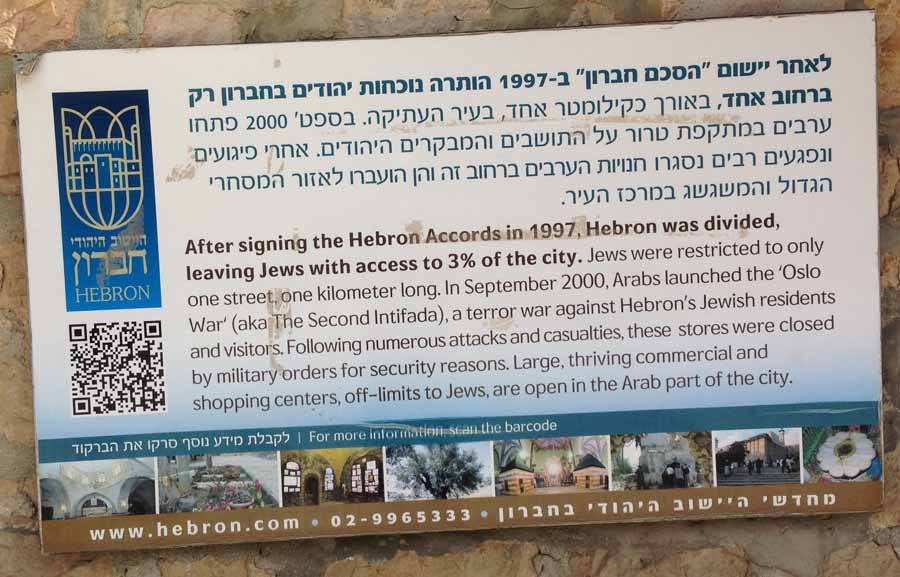

In the Jewish settler area of Hebron, an apparent ghost town of closed shops, houses populated by Palestinians who are forbidden to use their front doors or drive on the streets, and Israelis who seem to live almost entirely indoors or in walled courtyards, a series of informative signs trace the history and current situation of “Jews” in Hebron.

I put the word “Jews” in quotation marks because in this instance I’m quoting a particular sign I photographed, which describes the city’s “large, thriving commercial and shopping centers, off-limits to Jews…” The stress on “large” and “thriving” underlines the point that, although 3% of Hebron’s physical area — the urban center of the southern West Bank — is off-limits to the city’s 200,000 Palestinian residents (both Muslim and Christian), with checkpoints manned by soldiers to enforce that prohibition, the remaining 97% of the city is open to Palestinians and off-limits to Jews…

I put the word “Jews” in quotation marks because in this instance I’m quoting a particular sign I photographed, which describes the city’s “large, thriving commercial and shopping centers, off-limits to Jews…” The stress on “large” and “thriving” underlines the point that, although 3% of Hebron’s physical area — the urban center of the southern West Bank — is off-limits to the city’s 200,000 Palestinian residents (both Muslim and Christian), with checkpoints manned by soldiers to enforce that prohibition, the remaining 97% of the city is open to Palestinians and off-limits to Jews…

…except, in fact, it isn’t off-limits to Jews. Like all the other Palestinian cities, which are classified as “Area A,”1 most of Hebron is off-limits to Israelis, but open to Jews of all other nationalities — along with Muslims, Christians, Samaritans, atheists, and people of any other faith, or lack of faith. I was staying in a hotel in the thriving city center, eating in crowded restaurants, wandering the bustling streets, being importuned by eager merchants — and no one ever suggested that my being Jewish was an issue.

Even when a pair of Israeli soldiers stopped me at a checkpoint, asked my religion, and refused to let me pass because I was Jewish, they were preventing me from walking down the one-block, non-commercial street in front of the Ibrahimi mosque and directing me to go around by side streets to the city center.

The misleading wordplay is not the only problem with this sign — the elision of the city’s most famous terrorist attack, by a Jewish gunman at the mosque, might take precedence there2 — but I found it particularly striking because it so clearly conflicted with my own experience. By the time I reached Hebron I’d been on the West Bank for a week, talking with lots of people, including ardent Palestinian nationalists, and routinely identifying myself as Jewish (because I didn’t want anyone to think I was hiding that detail). Without exception, everyone responded that their problem was with Israelis or with Zionists, but not with Jews – as always in Muslim countries, I was treated to explanations of how Muslims, Jews, and Christians are all “people of the book,” and since this region has a particularly strong consciousness of the three religions’ historical coexistence, I was regaled with stories of Jewish friends and neighbors and in a couple of cases of Jewish relatives. So I was intensely aware that simply being Jewish does not get anyone barred from Palestinian cities.

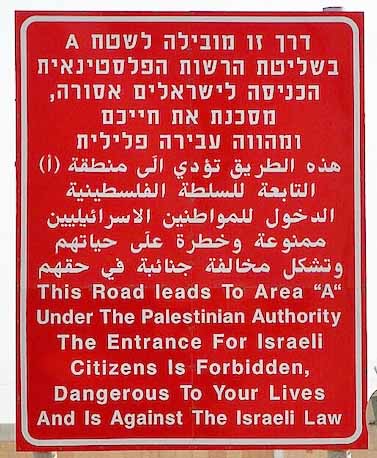

There’s plenty more to be said about all of that, but for a start it got me thinking about the ubiquitous signs marking entrances to “Area A.” For people unfamiliar with the region’s odd  divisions: the West Bank is often described as Palestinian territory, but only the urban areas, comprising a bit less than 20% of the total land, are under direct Palestinian control. Those are the scattered pockets classified as Area A, which Israelis are forbidden to enter (except soldiers, who enter them daily to conduct raids and arrests). Area B, accounting for another 20% of the West Bank, includes smaller Palestinian towns and villages, and is under Palestinian civil control with joint Palestinian/Israeli police/military control, and likewise barred to Israelis. The remaining 60% (actually, a bit more) is under full Israeli civil and military control; this includes the settlements, virtually all the unsettled countryside, and most of the main roads, all of which are open to Israelis – hence the signs at highway exits leading to any Palestinian city, town, or village warning Israeli drivers it is dangerous and illegal to go there.

divisions: the West Bank is often described as Palestinian territory, but only the urban areas, comprising a bit less than 20% of the total land, are under direct Palestinian control. Those are the scattered pockets classified as Area A, which Israelis are forbidden to enter (except soldiers, who enter them daily to conduct raids and arrests). Area B, accounting for another 20% of the West Bank, includes smaller Palestinian towns and villages, and is under Palestinian civil control with joint Palestinian/Israeli police/military control, and likewise barred to Israelis. The remaining 60% (actually, a bit more) is under full Israeli civil and military control; this includes the settlements, virtually all the unsettled countryside, and most of the main roads, all of which are open to Israelis – hence the signs at highway exits leading to any Palestinian city, town, or village warning Israeli drivers it is dangerous and illegal to go there.

Or maybe that should be “Israeli” drivers…

As I rode buses around the West Bank, I noticed that highway exits routinely have these signs warning Israelis that entering Area A is “dangerous to your lives” and “against the Israeli law” and many exits have checkpoints manned by soldiers controlling who can pass – but they are rarely if ever the same exits. The military checkpoints are at exits leading to Jewish settlements, to prevent Palestinians from taking those roads, while nothing but the signs prevents Israelis from entering areas A and B.

Since anyone could simply drive past the signs and no one ever checked my identification papers while traveling in the West Bank, I began asking Israelis if they bothered to follow the rules. At first I was asking Jewish Israelis, and overwhelmingly they said they did. Even the activists of Machsom [Checkpoint] Watch said they tended to stay in the areas allowed to them, and I was given to understand that only the most radical leftists traverse the boundaries…

…but then I was in Nazareth, a city of non-Jewish Israelis (variously identifying as Arab Israelis or Palestinian Israelis), and got to talking with a young woman who mentioned that everyone goes shopping in Jenin, the northernmost West Bank city, which is less than thirty kilometers away, because prices are much lower than in Israel.

Now, Israel prides itself on being a democracy with the same laws for all citizens, whatever their religion. And yes, I’d always taken that with several grains of salt, but I still assumed the official signs saying it was illegal for Israelis to go into Area A meant it was illegal for Israelis to go there – not just Israeli Jews. So I asked, “Isn’t it illegal for Israelis to go to the West Bank?”

“Oh, they don’t care if we go there,” the young woman replied. Then she laughed, and added: “They’d prefer if we’d all go there and stay.”

I took this to mean the laws were enforced selectively or capriciously – a familiar concept, by no means only in Israel – and the signs saying it is illegal for Israelis to enter Area A were routinely flouted by Arab/Palestinian Israelis… until I was doing some background research for this post and stumbled on B’Tselem’s checkpoint page, which includes the regulations for Jalameh checkpoint between Nazareth and Jenin – and read that crossing at Jalameh is forbidden “to Israelis, with the exception of Palestinians who are Israeli citizens.”

So… that suggests Israeli Arabs/Palestinians are in fact allowed into the areas where Israeli Jews are barred. And indeed, that’s the de facto situation… which shouldn’t be confused with de jure. A recent article in Haaretz says Israeli Arabs make up more than half the enrollment at the Arab American University of Jenin (among some 8,000 studying in West Bank universities) and there is a regular bus system between the campus and their homes in northern Israel. Which seems pretty official, until a note confirms what the young woman told me in Nazareth: “Officially, Israelis are prohibited from entering Area A, but the Israel Defense Forces does not enforce the ban when it comes to Arab citizens.”

Hence, the tale of two signs in the looking-glass world of the West Bank: one saying “Jews,” though in practice it only means Israelis; the other saying “Israelis,” though in practice it only means Jews.

When I mentioned to friends in the United States that I was headed there, many warned me to be careful — the West Bank is only mentioned in the US media when there is violence, so we associate it with violence. When I mentioned my plans to Jewish Israelis, the reactions were more varied: some were concerned about my safety, some puzzled why I wanted to go, some curious to hear what it is like, some irritated that I would expect to learn something about the region on a short visit — with the assumption I would come away more critical of Israeli policies — some encouraging me and saying they wished they could go there as well.

When I mentioned to friends in the United States that I was headed there, many warned me to be careful — the West Bank is only mentioned in the US media when there is violence, so we associate it with violence. When I mentioned my plans to Jewish Israelis, the reactions were more varied: some were concerned about my safety, some puzzled why I wanted to go, some curious to hear what it is like, some irritated that I would expect to learn something about the region on a short visit — with the assumption I would come away more critical of Israeli policies — some encouraging me and saying they wished they could go there as well. seeing someplace new, having a vacation. The Lonely Planet guidebook to Israel and the Palestinian Territories begins the relevant section on cheerful note:

seeing someplace new, having a vacation. The Lonely Planet guidebook to Israel and the Palestinian Territories begins the relevant section on cheerful note: I recommend any traveler visiting Israel spend some time on the West Bank — not just a day-trip to Bethlehem, but staying a while, going to nightclubs in Ramallah, exploring the old city of Nablus, visiting the Freedom Theater in Jenin, or hiking around the Jordan Valley — and be assured, there are plenty of other travelers making those trips (women as well as men, often on their own), and having a wonderful time.

I recommend any traveler visiting Israel spend some time on the West Bank — not just a day-trip to Bethlehem, but staying a while, going to nightclubs in Ramallah, exploring the old city of Nablus, visiting the Freedom Theater in Jenin, or hiking around the Jordan Valley — and be assured, there are plenty of other travelers making those trips (women as well as men, often on their own), and having a wonderful time. My first night in Ramallah, I got in a long discussion with Nidal Abu Maria, who owns

My first night in Ramallah, I got in a long discussion with Nidal Abu Maria, who owns  That choice is notable because France is not “normal” in the sense of being typical; on the contrary, it has long been held up as an ideal, particularly for German-speaking Central Europeans who dreamed of living wie Gott in Frankreich (like God in France), and more particularly for Central European Jews: Joseph Roth, arriving in France via Vienna and Berlin in the interwar years, wrote, “Paris is where the Eastern Jew begins to become a Western European.”

That choice is notable because France is not “normal” in the sense of being typical; on the contrary, it has long been held up as an ideal, particularly for German-speaking Central Europeans who dreamed of living wie Gott in Frankreich (like God in France), and more particularly for Central European Jews: Joseph Roth, arriving in France via Vienna and Berlin in the interwar years, wrote, “Paris is where the Eastern Jew begins to become a Western European.” solution, a one-state solution, or even a nasty war — but, in any case, resolved. A lot of conversations in Israel reinforce that impression, but after a while I realized that if I didn’t steer the talk in that direction it needn’t go there and most Israelis could probably go for days without mentioning the Occupied Territories or any Palestinian conflict. Because, quite simply, it doesn’t affect their day-to-day life. Yes, they see soldiers all around, often carrying automatic rifles, but being in the army is a basic part of growing up for most Israelis, so they’re used to that. And it is easy to live within a few minutes walk of the wall that blocks off the West Bank and never see it, or ever talk to a Palestinian — or to talk to Palestinians, but not about that.

solution, a one-state solution, or even a nasty war — but, in any case, resolved. A lot of conversations in Israel reinforce that impression, but after a while I realized that if I didn’t steer the talk in that direction it needn’t go there and most Israelis could probably go for days without mentioning the Occupied Territories or any Palestinian conflict. Because, quite simply, it doesn’t affect their day-to-day life. Yes, they see soldiers all around, often carrying automatic rifles, but being in the army is a basic part of growing up for most Israelis, so they’re used to that. And it is easy to live within a few minutes walk of the wall that blocks off the West Bank and never see it, or ever talk to a Palestinian — or to talk to Palestinians, but not about that. but if you frame them as ways to reduce tension and let off steam while extending the wall, maintaining the checkpoints, expanding the settlements, ensuring the refugees in Lebanon and Jordan do not return, and carrying out daily raids, arrests, and frequently killings on the West Bank — that is, while keeping things the way they are — they feel not like progress but like ways of normalizing the status quo.

but if you frame them as ways to reduce tension and let off steam while extending the wall, maintaining the checkpoints, expanding the settlements, ensuring the refugees in Lebanon and Jordan do not return, and carrying out daily raids, arrests, and frequently killings on the West Bank — that is, while keeping things the way they are — they feel not like progress but like ways of normalizing the status quo. April 20, 2018:

April 20, 2018: about his arrest and upcoming trial as a member of the Harrisburg 7, one of the famous conspiracy trials of the Vietnam War era. His fellow defendants were all Catholic clergy, including Phillip Berrigan, and Eqbal often told how his mother called him when she heard the news, saying: “I can understand you being against the Vietnam war. I can even understand you being arrested for this. But what are you doing being arrested with a group of priests and nuns?!”

about his arrest and upcoming trial as a member of the Harrisburg 7, one of the famous conspiracy trials of the Vietnam War era. His fellow defendants were all Catholic clergy, including Phillip Berrigan, and Eqbal often told how his mother called him when she heard the news, saying: “I can understand you being against the Vietnam war. I can even understand you being arrested for this. But what are you doing being arrested with a group of priests and nuns?!” was telling stories of his youth — that was the only time I heard him talk about seeing his father killed when he was a small boy, hiding behind his father’s legs as the killers attacked, and about fighting in Kashmir. My parents eventually drifted off to bed, but I stayed up, sixteen years old and enthralled. He talked about his student days in Paris, meeting young revolutionaries from around the world. He was particularly struck by the Algerian students who were going home to fight with the

was telling stories of his youth — that was the only time I heard him talk about seeing his father killed when he was a small boy, hiding behind his father’s legs as the killers attacked, and about fighting in Kashmir. My parents eventually drifted off to bed, but I stayed up, sixteen years old and enthralled. He talked about his student days in Paris, meeting young revolutionaries from around the world. He was particularly struck by the Algerian students who were going home to fight with the  There are other stories, but at the moment I keep coming back to that image of Exodus. Partly because I watched the movie in preparation for my trip to Israel/Palestine and recently wrote about

There are other stories, but at the moment I keep coming back to that image of Exodus. Partly because I watched the movie in preparation for my trip to Israel/Palestine and recently wrote about  I saw Eqbal more rarely in later years. He founded a university in Pakistan and was there much of the time, while I was touring as a musician and writing for the Boston Globe, so one way and another our paths didn’t cross. Our last meeting was at his retirement from Hampshire College, where he had taught for some years. Edward Said and Howard Zinn were there, among many others, and I spoke briefly about Eqbal’s cooking. At the party afterwards he asked me to come to Pakistan and work with him, and I’ll always wonder if he was serious about that, and how my life might have been different if he was and I’d gone.

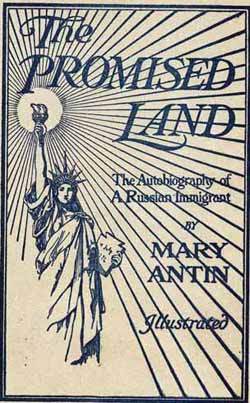

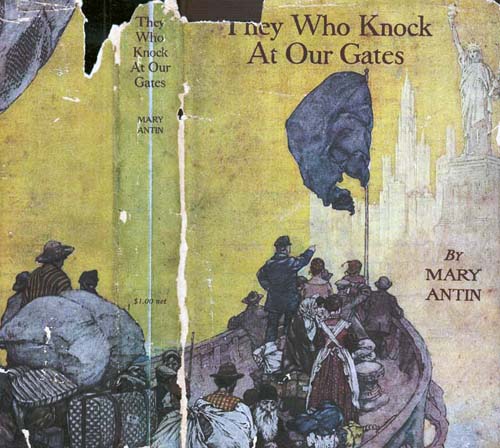

I saw Eqbal more rarely in later years. He founded a university in Pakistan and was there much of the time, while I was touring as a musician and writing for the Boston Globe, so one way and another our paths didn’t cross. Our last meeting was at his retirement from Hampshire College, where he had taught for some years. Edward Said and Howard Zinn were there, among many others, and I spoke briefly about Eqbal’s cooking. At the party afterwards he asked me to come to Pakistan and work with him, and I’ll always wonder if he was serious about that, and how my life might have been different if he was and I’d gone. “What terms of entry may we impose on the immigrant without infringing on his inalienable rights, as defined in our national charter?” Mary Antin asked in 1914. Her answer:

“What terms of entry may we impose on the immigrant without infringing on his inalienable rights, as defined in our national charter?” Mary Antin asked in 1914. Her answer: When I was a little girl, the world was divided into two parts; namely, Polotzk, the place where I lived, and a strange land called Russia. All the little girls I knew lived in Polotzk, with their fathers and mothers and friends. Russia was the place where one’s father went on business. It was so far off, and so many bad things happened there, that one’s mother and grandmother and grown-up aunts cried at the railroad station…

When I was a little girl, the world was divided into two parts; namely, Polotzk, the place where I lived, and a strange land called Russia. All the little girls I knew lived in Polotzk, with their fathers and mothers and friends. Russia was the place where one’s father went on business. It was so far off, and so many bad things happened there, that one’s mother and grandmother and grown-up aunts cried at the railroad station… Antin was an ardent believer in the ideals exemplified by Lazarus’s poem and The Declaration of Independence, and as an activist for women’s education and immigrant rights she fought to make her fellow citizens live up to them. When her memoir became a best-seller, she followed with a book-length polemic:

Antin was an ardent believer in the ideals exemplified by Lazarus’s poem and The Declaration of Independence, and as an activist for women’s education and immigrant rights she fought to make her fellow citizens live up to them. When her memoir became a best-seller, she followed with a book-length polemic:  citizenship and solid nation-state borders were still in their infancy, and modern readers will find her next passage surprising:

citizenship and solid nation-state borders were still in their infancy, and modern readers will find her next passage surprising: Some people see no indication of the future in the fact that race-blending has been going on here from the beginning of our history, because the elements we now get are said to differ from us more radically than the elements we assimilated in the past. To allay our anxiety on this point, we have only to remind ourselves that none of the great nations of Europe that present such a homogeneous front to-day arose from a single stock…

Some people see no indication of the future in the fact that race-blending has been going on here from the beginning of our history, because the elements we now get are said to differ from us more radically than the elements we assimilated in the past. To allay our anxiety on this point, we have only to remind ourselves that none of the great nations of Europe that present such a homogeneous front to-day arose from a single stock… article quoting her upbraiding immigrant bosses for forgetting their roots and mistreating striking garment workers.

article quoting her upbraiding immigrant bosses for forgetting their roots and mistreating striking garment workers. “Every time you see a cop on the beat, ask yourself what he is protecting, and from who.”

“Every time you see a cop on the beat, ask yourself what he is protecting, and from who.” And I’m glad all the museums and historical sites use the word “illegal,” because although I understand why some people prefer euphemisms like “undocumented” and “unauthorized,” the reality is that governments make laws to protect some people from other people — and when you argue that the people you support are not criminals, you are arguing that other people can justifiably be labeled that way.

And I’m glad all the museums and historical sites use the word “illegal,” because although I understand why some people prefer euphemisms like “undocumented” and “unauthorized,” the reality is that governments make laws to protect some people from other people — and when you argue that the people you support are not criminals, you are arguing that other people can justifiably be labeled that way. The Israeli contrast –narratives of desperate Jewish refugees throwing cans at soldiers seventy years ago, told to rally support for Jewish soldiers shooting desperate refugees throwing stones today – is particularly striking because the time and space are so compressed. But the essential contrast is so familiar as to be almost universal: virtually all national narratives include brave struggles against oppressive governments, and few governments maintain their power for long with clean hands.

The Israeli contrast –narratives of desperate Jewish refugees throwing cans at soldiers seventy years ago, told to rally support for Jewish soldiers shooting desperate refugees throwing stones today – is particularly striking because the time and space are so compressed. But the essential contrast is so familiar as to be almost universal: virtually all national narratives include brave struggles against oppressive governments, and few governments maintain their power for long with clean hands. As I write, Israeli troops are massed on the no man’s land separating Israel from Gaza, shooting tear gas grenades and live ammunition at Palestinian refugees who are gathered on the other side, throwing rocks, burning tires, and seeking to breech the barriers and send thousands of men, women and children across.

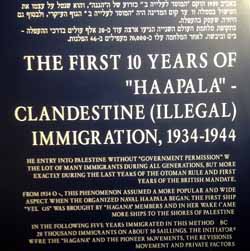

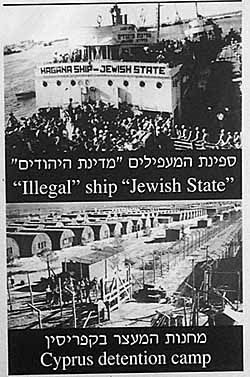

As I write, Israeli troops are massed on the no man’s land separating Israel from Gaza, shooting tear gas grenades and live ammunition at Palestinian refugees who are gathered on the other side, throwing rocks, burning tires, and seeking to breech the barriers and send thousands of men, women and children across. In Tel Aviv, the museum of the Hagganah, the Jewish army that faced British and Arab forces in the late 1940s, has a display honoring “Ha’apala – Clandestine (Illegal) Immigration, 1934-1944,” and two museums of the Etzel, the more radical Jewish underground, likewise celebrate the brave men and women who smuggled Jewish refugees into Palestine, defying the British army and even the Haggana, which in some periods helped the British, much as the Palestinian Authority’s police now work with Israeli forces to control illegal migration from the West Bank.

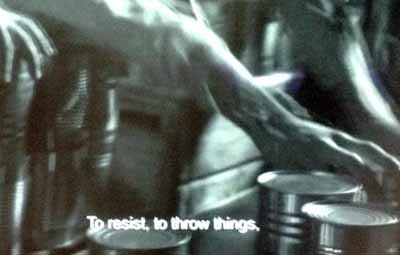

In Tel Aviv, the museum of the Hagganah, the Jewish army that faced British and Arab forces in the late 1940s, has a display honoring “Ha’apala – Clandestine (Illegal) Immigration, 1934-1944,” and two museums of the Etzel, the more radical Jewish underground, likewise celebrate the brave men and women who smuggled Jewish refugees into Palestine, defying the British army and even the Haggana, which in some periods helped the British, much as the Palestinian Authority’s police now work with Israeli forces to control illegal migration from the West Bank. Itzak Belfer, one of the passengers, describes how the British troops were massed on the deck of the destroyer, and someone brought up boxes of tin cans to throw at the soldiers. One of the men commanding the ship for the Palyam, the Jewish rebel navy, recalls: “We told them to give the British a hard time — to resist, to throw things, not let them board the ship, and maybe we could make it to the shore.”

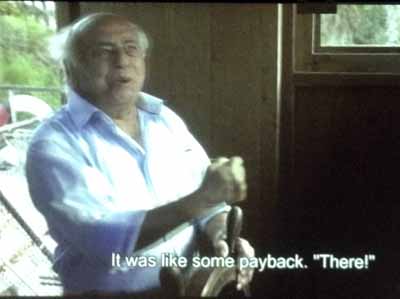

Itzak Belfer, one of the passengers, describes how the British troops were massed on the deck of the destroyer, and someone brought up boxes of tin cans to throw at the soldiers. One of the men commanding the ship for the Palyam, the Jewish rebel navy, recalls: “We told them to give the British a hard time — to resist, to throw things, not let them board the ship, and maybe we could make it to the shore.” The British soldiers began to board, and Belfer, his voice thrilling at the memory, recalls throwing the cans of food at them: “That kind of can, when someone throws it, it can do a lot of damage.” Then the Palyam man on the ship’s bridge angrily turned the wheel and rammed their boat into the destroyer. “We were all knocked down,” Belfer says, but “We all felt like… ‘We did it! We showed them!’”

The British soldiers began to board, and Belfer, his voice thrilling at the memory, recalls throwing the cans of food at them: “That kind of can, when someone throws it, it can do a lot of damage.” Then the Palyam man on the ship’s bridge angrily turned the wheel and rammed their boat into the destroyer. “We were all knocked down,” Belfer says, but “We all felt like… ‘We did it! We showed them!’”