There has been a lot of talk in recent years about “cultural appropriation.” The point tends to be that it is appropriate for some people to wear certain costumes or perform certain kinds of music because that is part of their culture, but it is appropriation for other people to wear those costumes or perform that music, because it is not part of their culture.

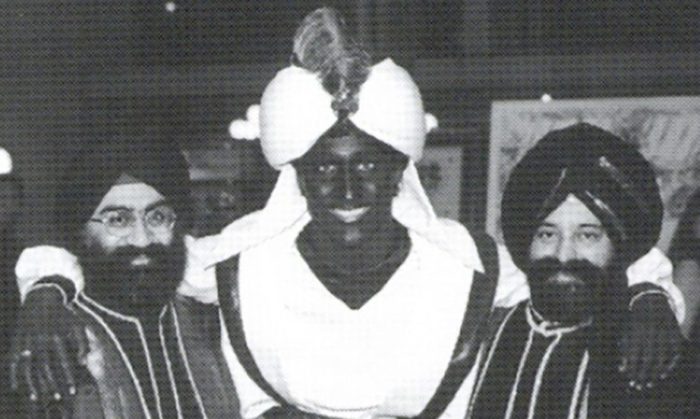

Having spent much of my life as a white guy playing and writing about blues, this conversation is very familiar to me, and I recently have been thinking, reading, and talking with people about it more than ever. So I was interested when a news story broke about Justin Trudeau, Canada’s Prime Minister, darkening his skin and donning a robe and turban to go to a costume party as Aladdin, and that sparked the following meditation.

A lot of people have referred to Trudeau’s makeup as blackface, and my first reaction was to say, “No, it’s not.” Because blackface is not just white people darkening their skin; it is a quite specific kind of makeup.

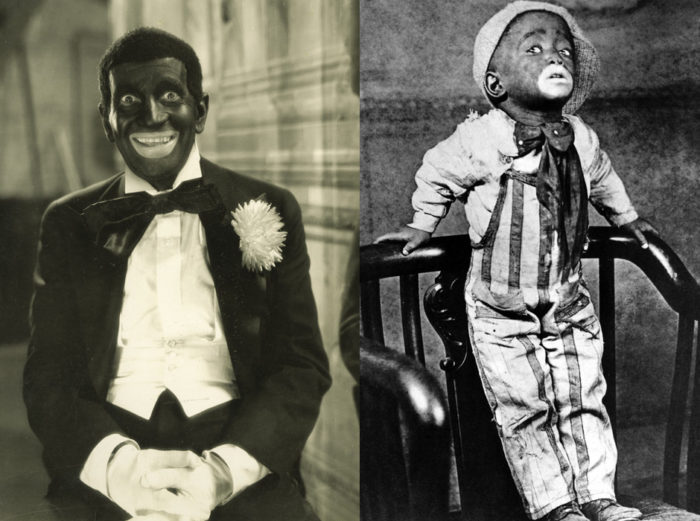

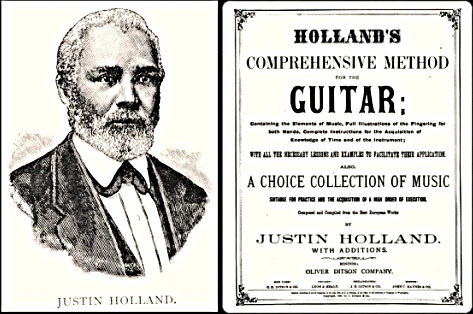

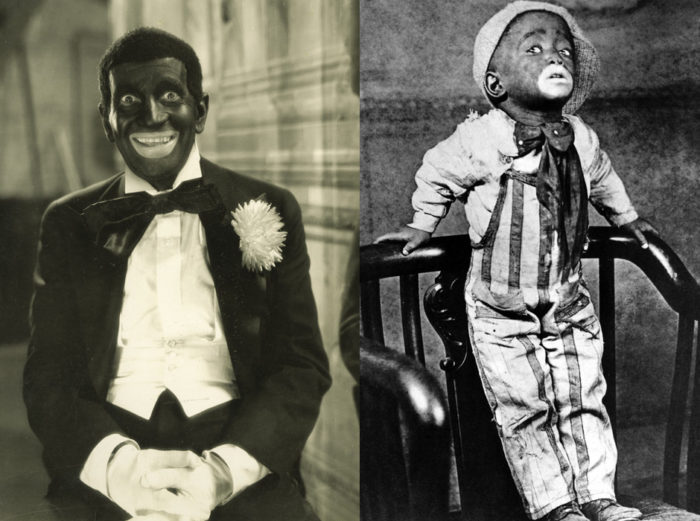

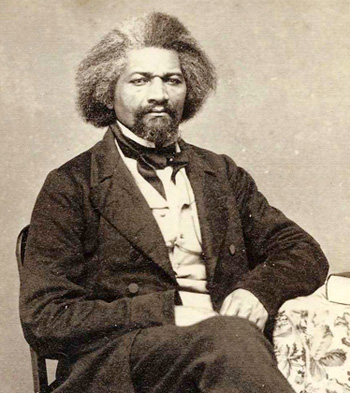

Both of these performers are in blackface. On the left is Bert Williams, an African American singer and comedian born in the Bahamas and raised in California, who was one of the most brilliant and influential Black performers of the early twentieth century. On the right is Al Jolson, a Jewish singer born in Lithuania and raised in New York.

In modern US racial terms Williams was Black and Jolson was white, but it would be ridiculous to argue that the make-up was not racist when Williams wore it. The tradition of blackface makeup is racist, whatever the ancestry of the person wearing it, and the fact that for many decades Black comedians had to use that make-up to have successful careers is at least as ugly as the fact that white comedians used it. Indeed, most Black comedians stopped wearing it by the 1940s — when many white comedians were still wearing it — because they were particularly aware of what it represented.

But this stuff can get complicated…

Sammy Davis Jr. recalled in his autobiography that when he was three years old and started working in vaudeville with his father and uncle, his uncle helped him put on blackface makeup, then told him: “Now you look like Al Jolson.”

Jolson had just hit internationally in The Jazz Singer, the first successful movie with sound, and for a while he was the most popular stage performer in the United States. So in that context you could say Davis wasn’t made up to look like a Black person, or even as the racist stereotype of a Black person — you could say he was made up to look like a Jewish movie star. As he tells the story, he seems to have thought it was fun to look like a Jewish movie star, and throughout his later career he continued to feature impressions of white singers and movie stars in his act.

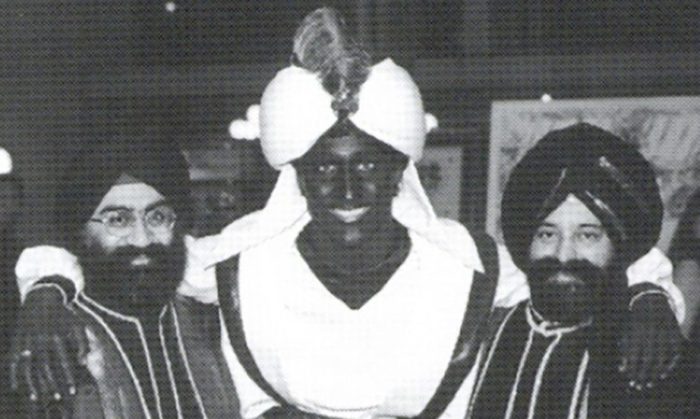

This is the only picture I’ve found of Davis in that makeup, and I’m not even sure he’s wearing black make-up — he describes his uncle applying burnt cork to his face, but in this photo the most obvious makeup is the white greasepaint around his mouth. So, in a weird way, you could argue he’s actually wearing whiteface…

…though, obviously, in a larger sense it’s still blackface.

My point is not that a Black kid wearing white makeup to look like a white performer in blackface makes the makeup less racist or offensive. My point is is that a Black kid performing in that makeup, in that context, was unquestionably racist, and also weird and complicated.

Getting back to the Trudeau/ Aladdin story: when I read what everyone had written about it I found that most writers do not describe his make-up as blackface—

They describe it as brownface, a recent term for white actors making themselves up as Arabs, Latinos, and other people whose ancestry is neither African nor European.

For example, there were protests against the new live-action Disney production of Aladdin for using brownface, because some of the actors and extras are Europeans made up to look like Arabs.

An odd twist to those protests is that a lot of people argued that the production should have hired Pakistani, Indian, or Bangladeshi actors — which is odd because the original Aladdin character was from somewhere in the region of present-day Iraq or Syria. The historical source of his story seems to have been a Syrian Maronite Christian and, in terms of ancestry and phenotype, Syrians and Iraqis are closer to Greeks or southern Italians than they are to Indians or Pakistanis.

That does not necessarily mean the protesters were wrong, because whatever we are talking about when we discuss race, it is not simply a matter of ancestry or phenotype.

I recently heard Imani Perry give a talk at the Philadelphia library, and she made the point that whiteness in the sense we use that term in the United States or Europe is not a color: it is the absence of color. It is not a particular ethnicity: it is the absence of ethnicity.*

If that is what we mean by “white” — that it is what people in Europe and the United States call those of us who are not marked as “ethnic” — by this Eurocentric standard it makes perfect sense to argue that Iraqis, Syrians, Indians, and Pakistanis are in a single category, all regarded as brown ethnics, while Greeks and Italians are white.

There is no better way to illustrate that point than by showing a picture of Trudeau at the notorious costume party:

Because the two men with him look like they could well be Syrian or Iraqi, and whatever the point of his make-up, it clearly does not make him look like them.

This raises an obvious question: of course it was bizarrely racialist for Trudeau to wear dark brown make-up to look like a character who, in real life, probably had roughly the same skin color as Trudeau. It is a weirdly extreme way of exaggerating and marking the character as non-white…

…but would it have been ok for Trudeau to go to a party in that robe and turban if he had not worn any make-up?

Or would it have been like Katy Perry’s geisha costume?

Perry was widely criticized for performing in this costume, and many people described it as yellowface, another recent coinage applied to white performers who masquerade as Asian.

The logic of this criticism is obvious, but the odd thing in this instance is that, in terms of its actual color, Perry’s make-up made her skin whiter than normal, because  Japanese geishas traditionally whiten their faces with rice powder. If we agree that Perry is white, in color-swatch terms it would seem ridiculous to protest against her wearing white make-up…

Japanese geishas traditionally whiten their faces with rice powder. If we agree that Perry is white, in color-swatch terms it would seem ridiculous to protest against her wearing white make-up…

…but, as we all know, this is not about color in the color-swatch sense.

Which said, the subject of white make-up takes me down another odd historical rabbit hole:

Many of you will recognize this singer from the movie Casablanca…

His given name was Arthur Wilson, but he was known as Dooley Wilson. He got that nickname when he was working in African American vaudeville as an Irish imitator, featuring a popular Irish dialect song, “Mr. Dooley.” For that act he wore what some modern writers call “whiteface” makeup, which makes sense because it made him look like an ethnic European…

…but scholars of ethnic vaudeville often refer to the comic Irish acts of this period as greenface, because those performers weren’t imitating ordinary white people — they were specifically imitating Irish immigrants, who were racially defined and comically stereotyped ethnics. In fact, a lot of blackface minstrel comedy was adopted from “Paddy” acts, which remained popular in Britain and the United States through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

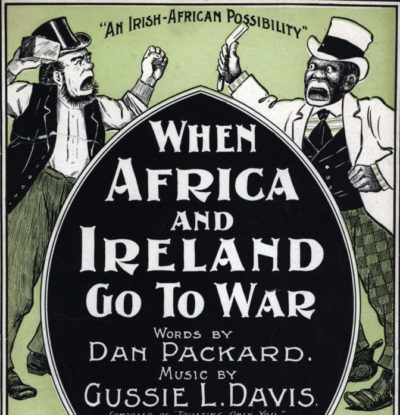

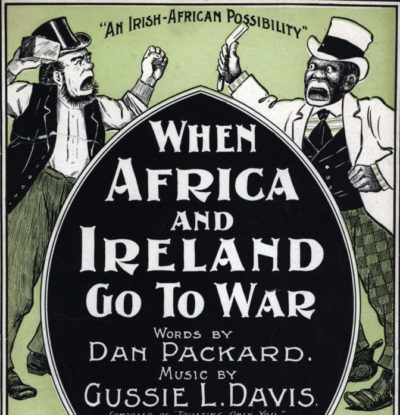

The two stereotypes occasionally overlapped, as in this comic song from 1898:

Gussie Davis, who composed the melody, was a well-known African American songwriter, and I have no information about Dan Packard’s ethnicity, but he wrote several popular “coon songs,” as blackface songs were labeled in the ragtime era.

A lot has been written about the racism of the blackface tradition, but virtually nothing about African American entertainers who performed other ethnicities. That is an omission worth correcting, since although Wilson’s choice to perform his Irish character in white make-up seems to have been relatively rare, “ethnic delineators” were almost as popular in Black vaudeville as in white vaudeville.

An ad from 1900 in the Indianapolis Freeman — one of the main African American newspapers — touted Louis Vasnier, a singing and dialect comedian who presented “Natural face expressions in five different dialects, no make up – Negro, Dutch, Dago, Irish and French.” It described him as “the only colored comedian who can do this,” but he soon had plenty of competitors. John Moore, for example, whose range included “Italian, Hebrew, Indian, Chink, Turk, villain (high and low class), straight man and blackface.”

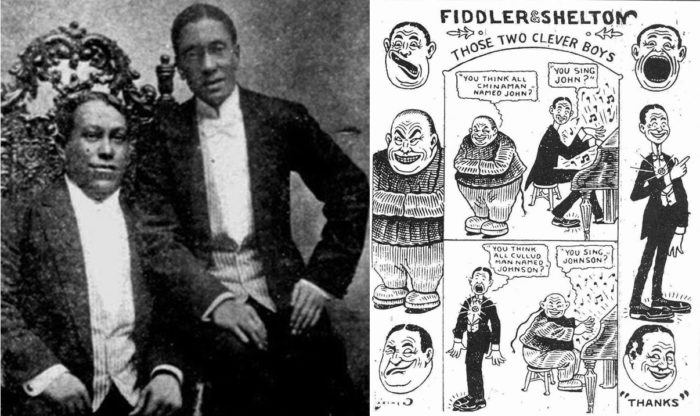

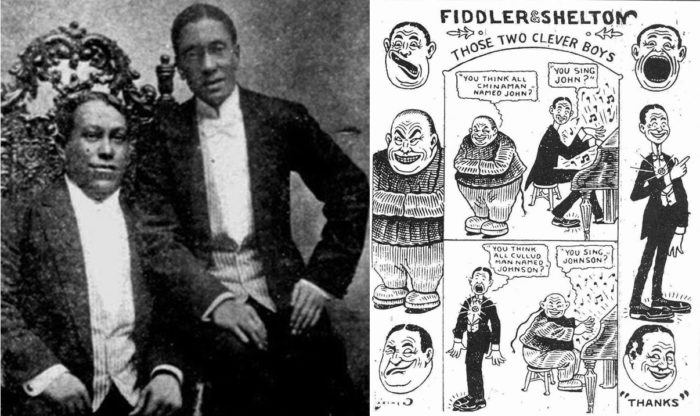

There are very few surviving images of these artists, but here is a photo of the popular duo of Fiddler and Shelton, who were popular for what we would now call a yellowface act, and a cartoon with a portion of their routine:

As with Vasnier, they were by no means unique. A review of Pinkey & Walker said: “As delineators of oriental characters they go to the head of the class. ‘Chinee’ Walker has already won his laurels as a ‘chink’ impersonator… His ‘Dago’ is equally as strong.” Chinese acts seem to have been particularly popular in Black vaudeville: I’ve found mentions of ten men who did them, including the jazz clarinet virtuoso Sidney Bechet, as well as couple of women.

Most comedians in Black vaudeville were men, and relatively few women seem to have specialized in ethnic material, but Lena Henderson was commended for her “splendid interpretation of Irish character singing,” the reviewer noting she “looks Irish all right, and dressed in green,” and Margie Crosby performed songs in Yiddish and was billed as “the girl with the Jewish face.”

H. Qualli Clark, an associate of W.C. Handy who composed the jazz standard “Shake it and Break It,” was likewise known for “Hebrew” imitations, one reviewer writing: “At times it was hard to believe he was a colored man, so perfect was his accent and so realistically faithful were his portrayals of a real Jew.” Among his competitors, Leroy Gresham was so successful that he was known for the rest of his career as “Kike” Gresham, though he also did blackface, Italian, and female impersonations.

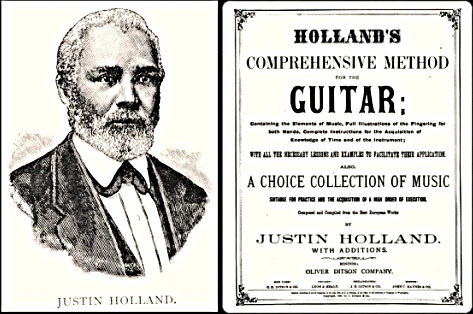

A lot has been written about Irish and Jewish performers who worked in blackface, and a fair amount about those who did Irish or Hebrew acts, but I’ve never seen even a substantial paragraph about Black ethnic imitators. One reason is that there has been relatively little research on African American vaudeville in general, and another is that the study of Black performers has tended to ignore or gloss over people whose work does not fit  within categories marked as Black culture. There is a great deal of writing on Black artists who performed ragtime, blues, and jazz, but the deep history of African American classical music has had far less study, and likewise the many Black singers and musicians who performed in other styles that were not marked as Black, such as mainstream pop, hillbilly, Hawaiian, Italian, and so forth.

within categories marked as Black culture. There is a great deal of writing on Black artists who performed ragtime, blues, and jazz, but the deep history of African American classical music has had far less study, and likewise the many Black singers and musicians who performed in other styles that were not marked as Black, such as mainstream pop, hillbilly, Hawaiian, Italian, and so forth.

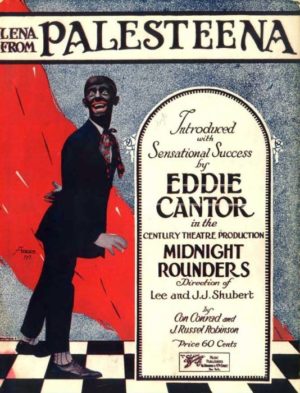

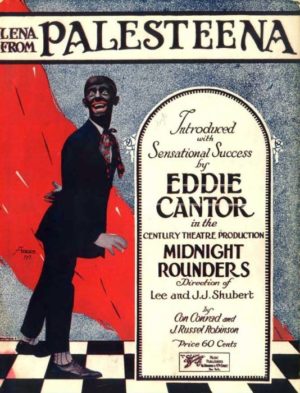

Another reason is the extent to which blackface minstrel shows have overshadowed all the other kinds of ethnic comedy. Along with professional minstrel troupes and solo stars like Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor, thousands of amateurs blacked up with burnt cork and did songs and comedy in exaggerated “darky” dialect. In comparison, the number of artists who explicitly imitated other ethnic groups was smaller, and the number of African American artists who did that was smaller still — besides which many (perhaps most) of them seem to have worked in blackface even when they were playing Europeans. Dooley Wilson was not the only one to use white make-up — a review of a Chinese impersonator named George Catlin actually criticized him for making up “too white” — but early mention of Qualli Clark’s act refers to his “blackface Jewish and Italian dialect character singing,” and Hen Wise was likewise noted for his appearance as a “blackface Hebrew…”

…which makes exactly as much sense as Justin Trudeau appearing as a blackface Syrian or Iraqi.

The fact that so many Black performers did ethnic acts does not make those acts less offensive. The portrayals of Irish, Jews, Chinese, and Italians as comical foreigners went along with discrimination in housing and employment, and by the 1920s ethnic stereotyping led to tight quotas on immigration from eastern and southern Europe, while by the 1880s Asians had been excluded both from entry and US citizenship.

It is common for people who have few victories to savor those few, and for people with little power to exercise that power on those with still less. In the battle to be recognized as full citizens, it was natural for African Americans to join in mocking immigrant outsiders, just as it was natural to join with immigrants when their interests intersected. By the same token, it was natural for immigrants striving to become fully American to assimilate American racial prejudices.

Periods of high immigration and intense anti-immigrant agitation come and go, but the bedrock of anti-Black racism remains. The Black ethnic delineators are an interesting byway of US culture, but their history does not in any way mitigate the enduring racism of blackface minstrelsy. On the contrary, the fact that you could perform pretty much any kind of ethnic caricature in blackface underlines the extent to which racism directed at African Americans has served as a more general paradigm.

Periods of high immigration and intense anti-immigrant agitation come and go, but the bedrock of anti-Black racism remains. The Black ethnic delineators are an interesting byway of US culture, but their history does not in any way mitigate the enduring racism of blackface minstrelsy. On the contrary, the fact that you could perform pretty much any kind of ethnic caricature in blackface underlines the extent to which racism directed at African Americans has served as a more general paradigm.

That is what it means when recent historians describe Irish, Italians, or Jews as “becoming white” — not that they came to be considered Anglo-Saxon, but that they ceased to be racialized the way African Americans are racialized. Native Americans were the defining “other” of the colonial period, but for the last two centuries the opposite of white in the United States has been Black, and other ethnicities have been able to blend into an American norm because Black Americans remained outside — as Toni Morrison reframed the melting pot metaphor, other people could melt because “[Black people] were the pot.”

That is one of the tricky things about the current term “people of color.” It implies a unifying category that includes everyone not marked as “white,” but to be “colored” in the United States has traditionally meant to be Black, and blackness continues to play a unique role in the American imaginary. That is in part because African Americans have such a deep history of oppression, discrimination, and stereotyping in the United States, but also because they have played such a central role in shaping American culture.

As a historian of popular music, I’m intensely aware of the way other groups have become “American” by emulating Black culture — “becoming white” by first becoming somewhat black. The original blackface minstrel stars were often Irish immigrants or their offspring; the early “white” jazz musicians who came north from New Orleans were mostly Italians, as were the “white” urban rock ‘n’ rollers.  I live up the street from a mural of South Philadelphia singers of the 1950s, and aside from the Jewish Eddie Fisher and the Black Chubby Checker, all the others are Italian (though many changed their names to play down their ethnicity, Bobby Ridarelli becoming Bobby Rydell, Jimmy Ercolani becoming Jimmy Darren).

I live up the street from a mural of South Philadelphia singers of the 1950s, and aside from the Jewish Eddie Fisher and the Black Chubby Checker, all the others are Italian (though many changed their names to play down their ethnicity, Bobby Ridarelli becoming Bobby Rydell, Jimmy Ercolani becoming Jimmy Darren).

Some people argue that those young Irish, Jewish, and Italian artists were expressing their love of Black culture, not appropriating it — and taken one by one, as individuals, that makes sense. But they weren’t taken one by one: in both the jazz age and the golden age of rock ‘n’ roll, the American mainstream consistently welcomed them into venues and played their recordings in situations where Black artists were not heard — and that contrast with Black artists cemented their status as members of the white mainstream.

There is obviously far, far more to be said about all of this, but for now I’ll leave it there. I am trying to complicate some familiar discussions, but inevitably have simplified others, and will go on to explore all of this in more depth. For the moment, these are a few unfamiliar facts and passing thoughts. For the future, I look forward to many more conversations.

[Thanks to Lynn Abbott for introducing me to the subject of ethnic delineators in African American vaudeville.]

*I took notes during Imani Perry’s talk, so am reasonably sure she said this, but I recently checked with her and she says it doesn’t sound familiar. If I reworked or misunderstood her ideas, I nonetheless got this impression from hearing her, and since I find the formulation useful I’m crediting her, with this caveat.

five months: the region’s only university; the oldest Christian church; a mosque; the zoo; a cultural center; an orphanage; a park—the trees bulldozed—and smaller places: a bakery, a pizzeria…

five months: the region’s only university; the oldest Christian church; a mosque; the zoo; a cultural center; an orphanage; a park—the trees bulldozed—and smaller places: a bakery, a pizzeria… The Post story refers to this as “urbicide,” the destruction of a city, but it is more than that, and does not require an academic term. It is an attempt to destroy memory; to destroy culture; to destroy hope.

The Post story refers to this as “urbicide,” the destruction of a city, but it is more than that, and does not require an academic term. It is an attempt to destroy memory; to destroy culture; to destroy hope. Vienna was not a paradise for Jews; it had a deep history of antisemitism, and my mother had direct memories of the Nazis marching, the books being burnt, the Jews being forced to scrub the streets; but when she took us back there, it was to share the Prater, the Riesenrad, the Stephansplatz, the Brueghels in the national museum, the restaurants where you could order a schnitzel and hear the cook hammering in the kitchen.

Vienna was not a paradise for Jews; it had a deep history of antisemitism, and my mother had direct memories of the Nazis marching, the books being burnt, the Jews being forced to scrub the streets; but when she took us back there, it was to share the Prater, the Riesenrad, the Stephansplatz, the Brueghels in the national museum, the restaurants where you could order a schnitzel and hear the cook hammering in the kitchen.

My mother grew up in Vienna. She was 14 years old when the German army marched in and was greeted with parades. She spent the next weeks running errands for her parents because it was dangerous for them to be out in the streets. They were not only Jewish, but longtime leftists, and they realized immediately that they would have to leave. It was easier in those first months, and they got out and got to the United States. My grandfather helped other relatives to get out. He tried to help his favorite brother and my mother’s favorite cousin, but for various reasons they did not want to leave until it was too late. They were shipped east in the cattle cars, and murdered.

My mother grew up in Vienna. She was 14 years old when the German army marched in and was greeted with parades. She spent the next weeks running errands for her parents because it was dangerous for them to be out in the streets. They were not only Jewish, but longtime leftists, and they realized immediately that they would have to leave. It was easier in those first months, and they got out and got to the United States. My grandfather helped other relatives to get out. He tried to help his favorite brother and my mother’s favorite cousin, but for various reasons they did not want to leave until it was too late. They were shipped east in the cattle cars, and murdered.

Japanese geishas traditionally whiten their faces with rice powder. If we agree that Perry is white, in color-swatch terms it would seem ridiculous to protest against her wearing white make-up…

Japanese geishas traditionally whiten their faces with rice powder. If we agree that Perry is white, in color-swatch terms it would seem ridiculous to protest against her wearing white make-up…

within categories marked as Black culture. There is a great deal of writing on Black artists who performed ragtime, blues, and jazz, but the deep history of African American classical music has had far less study, and likewise the many Black singers and musicians who performed in other styles that were not marked as Black, such as mainstream pop, hillbilly, Hawaiian, Italian, and so forth.

within categories marked as Black culture. There is a great deal of writing on Black artists who performed ragtime, blues, and jazz, but the deep history of African American classical music has had far less study, and likewise the many Black singers and musicians who performed in other styles that were not marked as Black, such as mainstream pop, hillbilly, Hawaiian, Italian, and so forth. Periods of high immigration and intense anti-immigrant agitation come and go, but the bedrock of anti-Black racism remains. The Black ethnic delineators are an interesting byway of US culture, but their history does not in any way mitigate the enduring racism of blackface minstrelsy. On the contrary, the fact that you could perform pretty much any kind of ethnic caricature in blackface underlines the extent to which racism directed at African Americans has served as a more general paradigm.

Periods of high immigration and intense anti-immigrant agitation come and go, but the bedrock of anti-Black racism remains. The Black ethnic delineators are an interesting byway of US culture, but their history does not in any way mitigate the enduring racism of blackface minstrelsy. On the contrary, the fact that you could perform pretty much any kind of ethnic caricature in blackface underlines the extent to which racism directed at African Americans has served as a more general paradigm. I live up the street from a mural of South Philadelphia singers of the 1950s, and aside from the Jewish Eddie Fisher and the Black Chubby Checker, all the others are Italian (though many changed their names to play down their ethnicity, Bobby Ridarelli becoming Bobby Rydell, Jimmy Ercolani becoming Jimmy Darren).

I live up the street from a mural of South Philadelphia singers of the 1950s, and aside from the Jewish Eddie Fisher and the Black Chubby Checker, all the others are Italian (though many changed their names to play down their ethnicity, Bobby Ridarelli becoming Bobby Rydell, Jimmy Ercolani becoming Jimmy Darren). Men, like bees, want elbow room. When the hive is overcrowded, the bees will swarm, and will be likely to take up their abode where they find the best prospect for honey. In matters of this sort, men are very much like bees…. The same mighty forces which have swept to our shores the overflowing populations of Europe; which have reduced the people of Ireland three millions below its normal standard; will operate in a similar manner upon the hungry population of China and other parts of Asia. Home has its charms, and native land has its charms, but hunger, oppression, and destitution, will dissolve these charms and send men in search of new countries and new homes….

Men, like bees, want elbow room. When the hive is overcrowded, the bees will swarm, and will be likely to take up their abode where they find the best prospect for honey. In matters of this sort, men are very much like bees…. The same mighty forces which have swept to our shores the overflowing populations of Europe; which have reduced the people of Ireland three millions below its normal standard; will operate in a similar manner upon the hungry population of China and other parts of Asia. Home has its charms, and native land has its charms, but hunger, oppression, and destitution, will dissolve these charms and send men in search of new countries and new homes…. I spent my second day in Hebron walking around, taking pictures, getting a better sense of where everything was. I went through a couple of full-scale checkpoints with turnstiles and metal detectors, and others with just a couple of soldiers with automatic rifles, and wherever I went they waved me through with a smile, even when I set off the metal detectors — I was asked my nationality a couple of times and once asked for my passport, but just to see I had one, not to open it and check my photo… because I was obviously a tourist and everybody wants more of those.

I spent my second day in Hebron walking around, taking pictures, getting a better sense of where everything was. I went through a couple of full-scale checkpoints with turnstiles and metal detectors, and others with just a couple of soldiers with automatic rifles, and wherever I went they waved me through with a smile, even when I set off the metal detectors — I was asked my nationality a couple of times and once asked for my passport, but just to see I had one, not to open it and check my photo… because I was obviously a tourist and everybody wants more of those. the hills above… it’s weird and fascinating, because these inimical populations are completely intertwined, sometimes on different floors of the same house. And no one was bothering me — some people didn’t return my hellos, but the soldiers were consistently polite and cheerful, and when I asked if I could take their picture they said, “Sure, you can do anything you want…”

the hills above… it’s weird and fascinating, because these inimical populations are completely intertwined, sometimes on different floors of the same house. And no one was bothering me — some people didn’t return my hellos, but the soldiers were consistently polite and cheerful, and when I asked if I could take their picture they said, “Sure, you can do anything you want…” They were very helpful, telling me how things were different in various periods, and we gradually made our way down the hill and back to the street in front of the Ibrahimi Mosque, which I had already walked up and down at least three times. They introduced me to a Palestinian man who runs a souvenir shop there, and while we were chatting the Israeli soldiers who were guarding that end of the street came over from the checkpoint and asked the women who they were and what they were doing. Then the women left to catch their ride back to Tel Aviv, and I had a coffee in the souvenir shop and headed back towards that street in front of the mosque, which was also the street to the hostel where I was staying…

They were very helpful, telling me how things were different in various periods, and we gradually made our way down the hill and back to the street in front of the Ibrahimi Mosque, which I had already walked up and down at least three times. They introduced me to a Palestinian man who runs a souvenir shop there, and while we were chatting the Israeli soldiers who were guarding that end of the street came over from the checkpoint and asked the women who they were and what they were doing. Then the women left to catch their ride back to Tel Aviv, and I had a coffee in the souvenir shop and headed back towards that street in front of the mosque, which was also the street to the hostel where I was staying… they’d seen me with. I said no, and they asked where I was going. I said I was going back to my hostel. They asked, “You are a Jew?” I said yes. They said, “You cannot go here.”

they’d seen me with. I said no, and they asked where I was going. I said I was going back to my hostel. They asked, “You are a Jew?” I said yes. They said, “You cannot go here.” I walked up the dirt road that led behind the mosque, into a thoroughly Arab neighborhood, wandered up dirt roads and down alleys, asked a couple of people for directions, and eventually wound my way down to the other end of the same street in front of the mosque… where another pair of soldiers who hadn’t seen me consorting with elderly Israeli peace observers waved me through with a smile. So that was that. I walked back through the market, bought a handful of almonds and a falafel sandwich with roast eggplant, hot pepper sauce, and pickled vegetables, retrieved my guitar and pack from the hostel, and caught a minibus to Bethlehem.

I walked up the dirt road that led behind the mosque, into a thoroughly Arab neighborhood, wandered up dirt roads and down alleys, asked a couple of people for directions, and eventually wound my way down to the other end of the same street in front of the mosque… where another pair of soldiers who hadn’t seen me consorting with elderly Israeli peace observers waved me through with a smile. So that was that. I walked back through the market, bought a handful of almonds and a falafel sandwich with roast eggplant, hot pepper sauce, and pickled vegetables, retrieved my guitar and pack from the hostel, and caught a minibus to Bethlehem.

I didn’t understand that until I spent a month traveling in Israel and the West Bank. I had heard about the wall there, both from supporters of the Israeli government who credit it with ending terrorist bombings and from supporters of the Palestinians who see it as an instrument for grabbing Palestinian land, dividing Palestinian farmers from their fields, making life difficult for Palestinians who need to cross into Israel, and reminding Palestinians that they are trapped and isolated.

I didn’t understand that until I spent a month traveling in Israel and the West Bank. I had heard about the wall there, both from supporters of the Israeli government who credit it with ending terrorist bombings and from supporters of the Palestinians who see it as an instrument for grabbing Palestinian land, dividing Palestinian farmers from their fields, making life difficult for Palestinians who need to cross into Israel, and reminding Palestinians that they are trapped and isolated.

and motion sensors. Given all the stories of Palestinian climbers, I would not be surprised if these less imposing stretches are actually a more effective barrier—but the towering concrete wall is far more impressive, and it struck me that its massive ugliness is no accident. Its size and weight are a constant reminder to Israeli Jews of the horrors lurking on the other side, the enemies so fearsome that mere wire cannot keep them out. It is theater; theater of fear.

and motion sensors. Given all the stories of Palestinian climbers, I would not be surprised if these less imposing stretches are actually a more effective barrier—but the towering concrete wall is far more impressive, and it struck me that its massive ugliness is no accident. Its size and weight are a constant reminder to Israeli Jews of the horrors lurking on the other side, the enemies so fearsome that mere wire cannot keep them out. It is theater; theater of fear. and what better way to divide than with a towering wall?

and what better way to divide than with a towering wall?

That was the original idea that drew people to travel as a caravan, and it remains the idea for the people involved. They set off this month because this is the best season to travel through Mexico, after the heat of summer and before the cold and rains of winter.

That was the original idea that drew people to travel as a caravan, and it remains the idea for the people involved. They set off this month because this is the best season to travel through Mexico, after the heat of summer and before the cold and rains of winter. I’m writing this post in Villers-Cotterêts, a small town about an hour outside Paris on the road to Laon. Like most tourists I came here because of Alexandre Dumas, France’s most famous writer, thanks to The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo, and dozens of other books. The walk from the center to the hotel where I’m staying led past the royal palace that inspired young Alexandre with dreams of derring-do, then down a wide and grassy lane bordered with towering trees to narrower path along an ancient, moss-covered stone wall. It felt like Dumas scenery, except on the other side of the wall was a modern low-income housing estate.

I’m writing this post in Villers-Cotterêts, a small town about an hour outside Paris on the road to Laon. Like most tourists I came here because of Alexandre Dumas, France’s most famous writer, thanks to The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo, and dozens of other books. The walk from the center to the hotel where I’m staying led past the royal palace that inspired young Alexandre with dreams of derring-do, then down a wide and grassy lane bordered with towering trees to narrower path along an ancient, moss-covered stone wall. It felt like Dumas scenery, except on the other side of the wall was a modern low-income housing estate. The streets and buildings in it are named for places and characters in Dumas’s novels, the people are the mix typical of modern France: some look like native Picards, some look West African, some wear Muslim headscarves.

The streets and buildings in it are named for places and characters in Dumas’s novels, the people are the mix typical of modern France: some look like native Picards, some look West African, some wear Muslim headscarves. European and African ancestry. He is from the Island of Mauritius and the action involves his romance with a lady from the island’s ruling class of French plantation owners. It’s an interesting book in a lot of ways, and one is Dumas’s insistence that the prejudice Georges faces from the wealthy French planters is a quirk of the colonial slave system. At the governor’s ball, his lady love is pleased to see him seated between two recently-arrived English ladies, since “she knew that the prejudice which pursued Georges in his native land possessed no influence on the minds of foreigners, and that it required a long residence in the island to cause an inhabitant of Europe to adopt it.”

European and African ancestry. He is from the Island of Mauritius and the action involves his romance with a lady from the island’s ruling class of French plantation owners. It’s an interesting book in a lot of ways, and one is Dumas’s insistence that the prejudice Georges faces from the wealthy French planters is a quirk of the colonial slave system. At the governor’s ball, his lady love is pleased to see him seated between two recently-arrived English ladies, since “she knew that the prejudice which pursued Georges in his native land possessed no influence on the minds of foreigners, and that it required a long residence in the island to cause an inhabitant of Europe to adopt it.” This is a complicated story, with plenty of contradictions. Dumas occasionally described himself as Mulatto, but more often was cagey and at times misleading. He always referred with great pride to his father, a general in the French army and hero of the Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, but tended to gloss over the details of his father’s youth and wrote in his memoirs that his father was known to the Austrians as “the Black Devil,” and owed “his brown complexion…to the mix of Indian and Caucasian races.” (That is “Caucasian” as in from the Caucasus, and a print in the Dumas museum here shows Dumas himself in traditional Caucasian garb.)

This is a complicated story, with plenty of contradictions. Dumas occasionally described himself as Mulatto, but more often was cagey and at times misleading. He always referred with great pride to his father, a general in the French army and hero of the Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, but tended to gloss over the details of his father’s youth and wrote in his memoirs that his father was known to the Austrians as “the Black Devil,” and owed “his brown complexion…to the mix of Indian and Caucasian races.” (That is “Caucasian” as in from the Caucasus, and a print in the Dumas museum here shows Dumas himself in traditional Caucasian garb.) sales contract for Thomas-Alexandre included a clause allowing his father to buy him back within five years. His father exercised the clause, brought him to France as his legitimate son, sent him to the best schools, and raised him as a French aristocrat. His siblings were never heard from again.

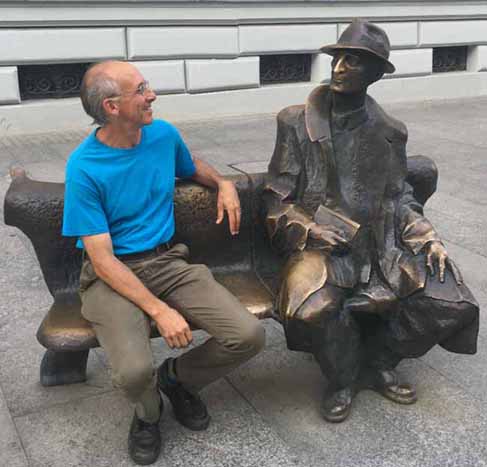

sales contract for Thomas-Alexandre included a clause allowing his father to buy him back within five years. His father exercised the clause, brought him to France as his legitimate son, sent him to the best schools, and raised him as a French aristocrat. His siblings were never heard from again. The answer turns out to be exquisitely complicated, and it’s going to take more than this visit to make any sense of it. On the one hand the town has a grand statue of Alexandre Dumas on the main square, and a Dumas museum with rooms dedicated to the general, the novelist, and Alexandre Dumas, fils (junior), who was likewise a famous writer. The stone plaque on the house where General Dumas died notes his African ancestry and his birth in Haiti, and the street in front of it has been the site of an annual celebration on May 10, the anniversary of France’s passage of a law abolishing slavery.

The answer turns out to be exquisitely complicated, and it’s going to take more than this visit to make any sense of it. On the one hand the town has a grand statue of Alexandre Dumas on the main square, and a Dumas museum with rooms dedicated to the general, the novelist, and Alexandre Dumas, fils (junior), who was likewise a famous writer. The stone plaque on the house where General Dumas died notes his African ancestry and his birth in Haiti, and the street in front of it has been the site of an annual celebration on May 10, the anniversary of France’s passage of a law abolishing slavery. sympathetic to newcomers from its ex-colonies, and declaring that the town government would no longer take part. All the news stories about this incident noted the irony of anti-immigrant activists standing under the statue of Alexandre Dumas and lamenting the demise of an ethnically homogeneous France.

sympathetic to newcomers from its ex-colonies, and declaring that the town government would no longer take part. All the news stories about this incident noted the irony of anti-immigrant activists standing under the statue of Alexandre Dumas and lamenting the demise of an ethnically homogeneous France.

Julian Tuwim. Tuwim is a major figure in Polish literature, a poet, songwriter, and author whose songs and children’s poems are still widely known and performed, but I came across him because of one piece that – not accidentally – was left out of the official five-volume edition of his collected works.

Julian Tuwim. Tuwim is a major figure in Polish literature, a poet, songwriter, and author whose songs and children’s poems are still widely known and performed, but I came across him because of one piece that – not accidentally – was left out of the official five-volume edition of his collected works. “I am a Pole because that’s how I like it. This is my completely private affair which I have no intention of explaining, clarifying, demonstrating or justifying to anyone. I do not divide Poles into ‘pure’ or ‘not pure,’ but leave that to the pure racists, to native and not native Hitlerites. I divide Poles, just as I do Jews and other peoples, into wise and stupid, polite and nasty, intelligent and dull, interesting and boring, injured and injuring, gentlemen and not gentlemen…”

“I am a Pole because that’s how I like it. This is my completely private affair which I have no intention of explaining, clarifying, demonstrating or justifying to anyone. I do not divide Poles into ‘pure’ or ‘not pure,’ but leave that to the pure racists, to native and not native Hitlerites. I divide Poles, just as I do Jews and other peoples, into wise and stupid, polite and nasty, intelligent and dull, interesting and boring, injured and injuring, gentlemen and not gentlemen…” But some of the complications and messiness feel very familiar to me. As those of you who follow my

But some of the complications and messiness feel very familiar to me. As those of you who follow my  Meanwhile, my mother grew up thoroughly Viennese, daughter of two physicians, one of whom was also a concert-quality pianist, immersed in Mozart, Goethe, the earthy Viennese street dialect, and the certainty that she was at the cultural center of the universe. Her childhood foods weren’t latkes and gefilte fish; they were schnitzel, Kaiserschmarrn, and pastries slathered in whipped cream. When the Nazis labeled her a Jew, that changed the course of her life but didn’t change how she thought about herself. She felt rejected by Vienna and often referred to herself not as Viennese but as European, but her views remained thoroughly Viennese, and socialist, and atheist.

Meanwhile, my mother grew up thoroughly Viennese, daughter of two physicians, one of whom was also a concert-quality pianist, immersed in Mozart, Goethe, the earthy Viennese street dialect, and the certainty that she was at the cultural center of the universe. Her childhood foods weren’t latkes and gefilte fish; they were schnitzel, Kaiserschmarrn, and pastries slathered in whipped cream. When the Nazis labeled her a Jew, that changed the course of her life but didn’t change how she thought about herself. She felt rejected by Vienna and often referred to herself not as Viennese but as European, but her views remained thoroughly Viennese, and socialist, and atheist.

996 other Viennese Jews, on November 29, 1941. I wasn’t sure why I wanted to go there, but now I know – it was a powerful experience to be where I know a particular family member was killed, on a particular day.

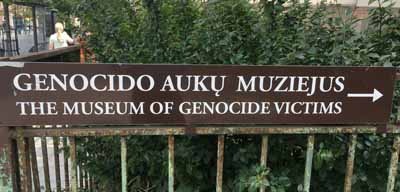

996 other Viennese Jews, on November 29, 1941. I wasn’t sure why I wanted to go there, but now I know – it was a powerful experience to be where I know a particular family member was killed, on a particular day. …the use of the word “genocide,” and specifically the use of Jewish deaths in service of the narrative of non-Jewish Lithuanian suffering is striking. For example, the panel giving numbers of Lithuanians killed: First, during almost fifty years under the Soviets between 1940-1990: 20-25,000 “prisoners who died”; 28,000 “died in deportation”; 21,500 “Partisans and their supporters killed.” Then, during the four years of German occupation between 1941-44: “240,000 killed (including about 200,000 Jews).” In parenthesis.

…the use of the word “genocide,” and specifically the use of Jewish deaths in service of the narrative of non-Jewish Lithuanian suffering is striking. For example, the panel giving numbers of Lithuanians killed: First, during almost fifty years under the Soviets between 1940-1990: 20-25,000 “prisoners who died”; 28,000 “died in deportation”; 21,500 “Partisans and their supporters killed.” Then, during the four years of German occupation between 1941-44: “240,000 killed (including about 200,000 Jews).” In parenthesis. I came to Lithuania following the story of my mother’s younger cousin Jutte, bringing her picture and the story of how she got stuck in Vienna, and the number of the transport that brought her to Kaunas, and the date when the 998 Viennese Jews on that train were chased up the hill at the Ninth Fort, pushed into mass graves, and shot – or in some cases shot, then pushed into mass graves. I wondered if the museum might be interested in having a copy of the photograph of Jutte and her mother, Gustl.

I came to Lithuania following the story of my mother’s younger cousin Jutte, bringing her picture and the story of how she got stuck in Vienna, and the number of the transport that brought her to Kaunas, and the date when the 998 Viennese Jews on that train were chased up the hill at the Ninth Fort, pushed into mass graves, and shot – or in some cases shot, then pushed into mass graves. I wondered if the museum might be interested in having a copy of the photograph of Jutte and her mother, Gustl. It gives the numbers of Lithuanian Jews killed, and displays personal items – eye glasses, shaving brushes, a pair of child’s shoes – found in the mass graves. It is a touching display. Not one Jew is named.

It gives the numbers of Lithuanian Jews killed, and displays personal items – eye glasses, shaving brushes, a pair of child’s shoes – found in the mass graves. It is a touching display. Not one Jew is named. There is a second museum in the fort itself, for those who wish to delve deeper. It does include rooms with photographs of individual Jews, their names, their stories. There is a powerful display on a transport of 878 French Jews killed here in 1944, the walls lined with named photographs, sponsored by “Les Familles et Amis des Déportés du Convoi 73, Paris (France).” There is a room about the Kaunas ghetto, with family pictures, names, and stories from survivors. There is a room about the escape of 64 prisoners who were brought in 1943 to burn the thousands of corpses, naming them and noting that 60 were Jews, along with three Russians and a Pole. There is a room with stories of survivors, saying what happened to them in later years. There is a room about the Japanese consul who in defiance of his government provided 6,000 Jews with exit visas. There is a room about “Lithuanians, the Saviours of the Jews,” with stories of non-Jewish Lithuanians who hid or helped their Jewish neighbors. And there is a room about Hitler and the genocide of European Jews, with names of 1,344 Jews from various parts of Europe who were killed here, each with their age and home town. Jutta and Gustl were not included – I looked for them, and the omission bothered me. But to continue…

There is a second museum in the fort itself, for those who wish to delve deeper. It does include rooms with photographs of individual Jews, their names, their stories. There is a powerful display on a transport of 878 French Jews killed here in 1944, the walls lined with named photographs, sponsored by “Les Familles et Amis des Déportés du Convoi 73, Paris (France).” There is a room about the Kaunas ghetto, with family pictures, names, and stories from survivors. There is a room about the escape of 64 prisoners who were brought in 1943 to burn the thousands of corpses, naming them and noting that 60 were Jews, along with three Russians and a Pole. There is a room with stories of survivors, saying what happened to them in later years. There is a room about the Japanese consul who in defiance of his government provided 6,000 Jews with exit visas. There is a room about “Lithuanians, the Saviours of the Jews,” with stories of non-Jewish Lithuanians who hid or helped their Jewish neighbors. And there is a room about Hitler and the genocide of European Jews, with names of 1,344 Jews from various parts of Europe who were killed here, each with their age and home town. Jutta and Gustl were not included – I looked for them, and the omission bothered me. But to continue… At the back of that room is a curtain, and if you go through there is a smaller room with a film showing the testimony of eight Lithuanian soldiers who were sentenced to death by the Soviet government in 1962 for participating in Nazi-organized massacres. One mimes standing at the edge of the mass graves and shooting down into the crowds of people, and explains how he would sell items he picked off the victims to buy a drink afterwards because “when you do such kind of thing you need to wet your whistle.”

At the back of that room is a curtain, and if you go through there is a smaller room with a film showing the testimony of eight Lithuanian soldiers who were sentenced to death by the Soviet government in 1962 for participating in Nazi-organized massacres. One mimes standing at the edge of the mass graves and shooting down into the crowds of people, and explains how he would sell items he picked off the victims to buy a drink afterwards because “when you do such kind of thing you need to wet your whistle.” At the Ninth Fort there are memorial stones placed by the city of Frankfurt in memory of the Jews transported from there to Kaunas; by the Families and Friends of the Jews transported and killed from France; by the city of Berlin in memory of 1000 Jewish children, women and men transported on Nov 17, 1941 and killed here on Nov 25; by the city of Munich in memory of 1000 Jews transported from there on November 20, 1941, and killed here five days later. There is no stone from Austria, or from the city of Vienna, commemorating the transport on November 23 that included my cousins. Like the Lithuanians, the Austrians prefer to recall the Nazi period as their own tragedy, not a Jewish tragedy. They do not deny that Jews were particularly selected for extermination, but they have their own issues, and feel we must remember it was a tough time, and everybody suffered…

At the Ninth Fort there are memorial stones placed by the city of Frankfurt in memory of the Jews transported from there to Kaunas; by the Families and Friends of the Jews transported and killed from France; by the city of Berlin in memory of 1000 Jewish children, women and men transported on Nov 17, 1941 and killed here on Nov 25; by the city of Munich in memory of 1000 Jews transported from there on November 20, 1941, and killed here five days later. There is no stone from Austria, or from the city of Vienna, commemorating the transport on November 23 that included my cousins. Like the Lithuanians, the Austrians prefer to recall the Nazi period as their own tragedy, not a Jewish tragedy. They do not deny that Jews were particularly selected for extermination, but they have their own issues, and feel we must remember it was a tough time, and everybody suffered… one photograph that, if you get close enough to read the minimal caption, turns out to show “the exhumation of remains of Soviet prisoners of war.” They aren’t denying that there were Soviet deaths in the Nazi period. If asked, I’m sure they would acknowledge that the Nazis killed millions of Soviet citizens, including some in Lithuania. That’s just not the story this museum is here to tell.

one photograph that, if you get close enough to read the minimal caption, turns out to show “the exhumation of remains of Soviet prisoners of war.” They aren’t denying that there were Soviet deaths in the Nazi period. If asked, I’m sure they would acknowledge that the Nazis killed millions of Soviet citizens, including some in Lithuania. That’s just not the story this museum is here to tell.