I grew up on old Tin Pan Alley pop tunes, thanks to a father who was born in 1906, knew all the hits of the 1920s, and was ready to perform them at the drop of a hat. I began working a few of them out on guitar in the 1970s, thanks to Dave Van Ronk, made a good part of my living in the 1980s playing them in restaurants and on cafe terraces in Antwerp, sometimes in the company of a fine fiddler, Nick Boons, and have already posted quite a few in this project… but honestly, I didn’t really immerse myself in this music until my wife, Sandrine, got serious about playing clarinet, hooked  up with Billy Novick for lessons, and Billy sent her to the Concord Inn, to hear Jimmy Mazzy and his gang — which led to a year or so of her playing with them every week (and with me, in between).

up with Billy Novick for lessons, and Billy sent her to the Concord Inn, to hear Jimmy Mazzy and his gang — which led to a year or so of her playing with them every week (and with me, in between).

I went every week and was consistently blown away by Jimmy’s musicianship and memory — I thought my father knew a lot of songs, but Jimmy is superhuman. Night after night, he would come up with things that were not only unfamiliar to me, but to the other musicians, some of whom had been playing trad jazz and swing for more than half a century.  He also played wonderful, idiosyncratic banjo, and sang with a wry tunefulness that captured the humor and sentiment of lyrics that I might otherwise have considered throw-aways.

He also played wonderful, idiosyncratic banjo, and sang with a wry tunefulness that captured the humor and sentiment of lyrics that I might otherwise have considered throw-aways.

Sandrine and I often came home from those sessions saying, “We have to try that one,” but I learned a long time ago that there are songs I like and there are songs that like me, and it’s nice when those categories overlap, but all too often they don’t. Which is a fancy way of saying a lot of songs that sounded great when Jimmy sang them with the band didn’t fall comfortably into my repertoire.

This one was an exception — I had never heard it before Jimmy sang it one night, but tried it with Sandrine the next day, loved playing and singing it, and have been doing it ever since. I know nothing more about it, though a glance at the artists featured on various versions of the sheet music suggests it was played by damn near everybody in the late 1930s.

Anyway, it was great being able to hear Jimmy and the gang every week, and then the Concord Inn changed their booking policy, Jimmy no longer had a regular venue for his jam sessions, and Sandrine and I moved to Philadelphia… which we love, but I miss those nights.

Anyway, that was my introduction to Los Tigres, and before I left Mexico I bought an LP of their greatest hits and a Guitarra fácil booklet with lyrics and chords to a bunch of their songs, along with LPs and booklets of Los Bravos del Norte, Los Cadetes de Linares, and some other norteño groups, and an LP of Los Teen Tops, who did “Rock de la cárcel.”

Anyway, that was my introduction to Los Tigres, and before I left Mexico I bought an LP of their greatest hits and a Guitarra fácil booklet with lyrics and chords to a bunch of their songs, along with LPs and booklets of Los Bravos del Norte, Los Cadetes de Linares, and some other norteño groups, and an LP of Los Teen Tops, who did “Rock de la cárcel.” I’ve enjoyed playing ranchera songs — an earlier post has my version of “

I’ve enjoyed playing ranchera songs — an earlier post has my version of “ The song was originally recorded by a mariachi singer named Joe Flores, but the Tigres’ version was definitive and made them into international stars, as well as spawning a string of low-budget action movies: first Contrabando y traición, then Mataron a Camelia, El hijo de Camelia, Emilio Varela vs. Camelia la texana… and who knows how many more. Los Tigres also made almost twenty movies, some of which are pretty interesting — for example La jaula de oro, about the tribulations of an undocumented Mexican immigrant raising a family in California.

The song was originally recorded by a mariachi singer named Joe Flores, but the Tigres’ version was definitive and made them into international stars, as well as spawning a string of low-budget action movies: first Contrabando y traición, then Mataron a Camelia, El hijo de Camelia, Emilio Varela vs. Camelia la texana… and who knows how many more. Los Tigres also made almost twenty movies, some of which are pretty interesting — for example La jaula de oro, about the tribulations of an undocumented Mexican immigrant raising a family in California. on guitar and “yee-hah,” and — for this project only, because he was recording and co-producing, Orrin Starr on mandolin. The photo in the video is from my only live show with that line-up, the cassette release party at Club Passim, which also included Mark Earley and Cormac McCarthy. A good bunch, and I get nostalgic listening to this.

on guitar and “yee-hah,” and — for this project only, because he was recording and co-producing, Orrin Starr on mandolin. The photo in the video is from my only live show with that line-up, the cassette release party at Club Passim, which also included Mark Earley and Cormac McCarthy. A good bunch, and I get nostalgic listening to this. My teacher was Geert van den Elsacker, a terrific musician and composer with a deep knowledge of traditional Flemish accordion styles — his main instrument, pictured on this lesson book, was the two-row diatonic — and French musette, which he played on a chromatic button instrument that looked fiendishly complicated, and when I was studying with him he was in the process of learning to play bandoneon and the Argentine tango repertoire. It was an education just being around him, and he was very patient with me — and I wish I could steer you towards his own performances, but he was tragically killed a year or so later in a stupid accident, hit by a car while bicycling through town.

My teacher was Geert van den Elsacker, a terrific musician and composer with a deep knowledge of traditional Flemish accordion styles — his main instrument, pictured on this lesson book, was the two-row diatonic — and French musette, which he played on a chromatic button instrument that looked fiendishly complicated, and when I was studying with him he was in the process of learning to play bandoneon and the Argentine tango repertoire. It was an education just being around him, and he was very patient with me — and I wish I could steer you towards his own performances, but he was tragically killed a year or so later in a stupid accident, hit by a car while bicycling through town. Hamilton defended a German immigrant printer named John Peter Zenger who was accused of printing several “low ballads” in his New York Weekly Journal, which, it was charged, contained “many things tending to sedition and faction, and to bring his Majesty’s government into contempt, and to disturb the peace thereof.” The judge did not accept the argument that the ballads were justifiable if they could not be proved false, and ordered the jury to convict, but Hamilton’s eloquence persuaded them otherwise and Zenger was acquitted — thus establishing a right to freedom of the press which was later codified in the US Constitution.

Hamilton defended a German immigrant printer named John Peter Zenger who was accused of printing several “low ballads” in his New York Weekly Journal, which, it was charged, contained “many things tending to sedition and faction, and to bring his Majesty’s government into contempt, and to disturb the peace thereof.” The judge did not accept the argument that the ballads were justifiable if they could not be proved false, and ordered the jury to convict, but Hamilton’s eloquence persuaded them otherwise and Zenger was acquitted — thus establishing a right to freedom of the press which was later codified in the US Constitution. and developing an enduring affection for horses and blue jeans. When he got back east, he wore jeans for the wedding, which was performed by the postmaster of Durham, New Hampshire.

and developing an enduring affection for horses and blue jeans. When he got back east, he wore jeans for the wedding, which was performed by the postmaster of Durham, New Hampshire.

and quirky player that most of my efforts just sounded like half-assed imitations of what he happened to play on a given day. I’ve kept playing his “

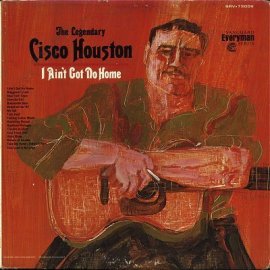

and quirky player that most of my efforts just sounded like half-assed imitations of what he happened to play on a given day. I’ve kept playing his “ The point of that digression is that when I started messing around with Jefferson’s music, this one had that extra connection, and when I figured out I couldn’t do it like he did, I could fall back on what I’d picked up from Cisco and Woody. So that’s kind of what I’ve done. I think the lyric I sing is mostly Jefferson’s, and the guitar part is based on his, with some licks borrowed from Sam McGee’s “

The point of that digression is that when I started messing around with Jefferson’s music, this one had that extra connection, and when I figured out I couldn’t do it like he did, I could fall back on what I’d picked up from Cisco and Woody. So that’s kind of what I’ve done. I think the lyric I sing is mostly Jefferson’s, and the guitar part is based on his, with some licks borrowed from Sam McGee’s “ often marked time between verses with a kind of boom-chang strum that comes from the same place as Woody’s style, and Woody played lots of blues. Not to mention the verse about robbing trains like Jesse James, an outlaw hero they all sang about.

often marked time between verses with a kind of boom-chang strum that comes from the same place as Woody’s style, and Woody played lots of blues. Not to mention the verse about robbing trains like Jesse James, an outlaw hero they all sang about. Sam Eskin, a self-educated folklorist and singer who was born in 1898 and began traveling around in the 1940s, recording singers all over the US and Mexico. I can’t say for sure where Eskin got this, but a likely source was David McIntosh, an Illinois folklorist who began working in the Ozarks in the 1930s and sang a virtually identical version at the National Folk Festival in 1937, which he apparently had collected from a Mr. Jones who lived south of Carbondale. (I have put

Sam Eskin, a self-educated folklorist and singer who was born in 1898 and began traveling around in the 1940s, recording singers all over the US and Mexico. I can’t say for sure where Eskin got this, but a likely source was David McIntosh, an Illinois folklorist who began working in the Ozarks in the 1930s and sang a virtually identical version at the National Folk Festival in 1937, which he apparently had collected from a Mr. Jones who lived south of Carbondale. (I have put  Bill mostly sang his own songs, but back in the early 1980s he also had some older songs he performed pretty regularly, and I was blown away by the way he dug into this lyric and made it come alive — I can still picture him onstage at the Nameless Coffeehouse in Cambridge, and see exactly the expression on his face as he sang, “I got so goddamn hungry, I could hide behind a straw.” He was acting as much as singing: a raw, skinny outlaw staking his final, wry testament.

Bill mostly sang his own songs, but back in the early 1980s he also had some older songs he performed pretty regularly, and I was blown away by the way he dug into this lyric and made it come alive — I can still picture him onstage at the Nameless Coffeehouse in Cambridge, and see exactly the expression on his face as he sang, “I got so goddamn hungry, I could hide behind a straw.” He was acting as much as singing: a raw, skinny outlaw staking his final, wry testament. I didn’t know any of that until I began working on this post; I just liked the song and played it more or less like Dave and Bill did, but I rarely performed it became my versions always seemed to drag. Then it was featured in Inside Llewyn Davis, and a whole bunch of new people did it, and my version felt even more superfluous, so I decided to leave it out of the Songobiography… until a few months ago it occurred to me that I could play it more like Buell Kazee would have done it, with the guitar keeping a quick banjo rhythm and the vocal line expanding and contracting to fit the mood of the lyric.

I didn’t know any of that until I began working on this post; I just liked the song and played it more or less like Dave and Bill did, but I rarely performed it became my versions always seemed to drag. Then it was featured in Inside Llewyn Davis, and a whole bunch of new people did it, and my version felt even more superfluous, so I decided to leave it out of the Songobiography… until a few months ago it occurred to me that I could play it more like Buell Kazee would have done it, with the guitar keeping a quick banjo rhythm and the vocal line expanding and contracting to fit the mood of the lyric. 1960 on a Life magazine set of Western songs featuring him and Rosemary Clooney, but Sam Hinton was also on that set, so could easily have been Crosby’s source. Dave was a big fan of Crosby’s jazz singing and I’d love to think Dave got the song from his recording, but Crosby left out the “Got so goddamn hungry” verse, so there must have been another intermediary. (Which said, I still kind of love the fact that Crosby seems to have made the first issued recording of this variant.)

1960 on a Life magazine set of Western songs featuring him and Rosemary Clooney, but Sam Hinton was also on that set, so could easily have been Crosby’s source. Dave was a big fan of Crosby’s jazz singing and I’d love to think Dave got the song from his recording, but Crosby left out the “Got so goddamn hungry” verse, so there must have been another intermediary. (Which said, I still kind of love the fact that Crosby seems to have made the first issued recording of this variant.) Stole My Gal” and over a dozen other songs. I learned this by ear off a Kweskin album, years before my ears were up to the task, and only realized how far off I was when I had the opportunity to open a concert for Guy Van Duser and Billy Novick and Billy very kindly offered to play clarinet on one of my songs. I suggested this one, we tried to run through it, and he informed me that I had the chords completely wrong. I think he may even have tried to learn my version, because he’s a really nice guy, but it was a complete mess, so we did something else.

Stole My Gal” and over a dozen other songs. I learned this by ear off a Kweskin album, years before my ears were up to the task, and only realized how far off I was when I had the opportunity to open a concert for Guy Van Duser and Billy Novick and Billy very kindly offered to play clarinet on one of my songs. I suggested this one, we tried to run through it, and he informed me that I had the chords completely wrong. I think he may even have tried to learn my version, because he’s a really nice guy, but it was a complete mess, so we did something else. book from the old days, illegally printed for cocktail lounge pianists , with 1,000 popular songs, three to a page, and no royalties paid to the songwriters or publishers. By that time, though, I wasn’t playing a lot of old pop tunes, so the song kind of languished in the hinterlands of my memory until I had the good fortune to marry Sandrine Sheon and she decided to pick up the clarinet she had played back in high school, and suddenly I needed a repertoire of early jazz and swing.

book from the old days, illegally printed for cocktail lounge pianists , with 1,000 popular songs, three to a page, and no royalties paid to the songwriters or publishers. By that time, though, I wasn’t playing a lot of old pop tunes, so the song kind of languished in the hinterlands of my memory until I had the good fortune to marry Sandrine Sheon and she decided to pick up the clarinet she had played back in high school, and suddenly I needed a repertoire of early jazz and swing. As for “All of Me,” I have no idea where or when I first heard it, or from whom. I know I had learned it by the mid-1970s and enjoyed playing it in appropriate circumstances, but I tended not to perform it onstage because it was also one of the tunes everyone else had learned and enjoyed playing, and there were plenty of less familiar standards to choose from. However… one day Sandrine and I were fooling around with “Somebody Stole My Gal,” and after a few choruses I felt like shifting to another song, and it occurred to me that the narrative could lead into “All of Me,” putting a new twist on the lyric. So here it is, or they are.

As for “All of Me,” I have no idea where or when I first heard it, or from whom. I know I had learned it by the mid-1970s and enjoyed playing it in appropriate circumstances, but I tended not to perform it onstage because it was also one of the tunes everyone else had learned and enjoyed playing, and there were plenty of less familiar standards to choose from. However… one day Sandrine and I were fooling around with “Somebody Stole My Gal,” and after a few choruses I felt like shifting to another song, and it occurred to me that the narrative could lead into “All of Me,” putting a new twist on the lyric. So here it is, or they are. couple of other bands and gave me Fadhili William’s phone number in the United States, explaining that William had moved there some years earlier, pursuing royalties for his world-famous song, “Malaika,” and was currently working in a gas station in New Jersey.

couple of other bands and gave me Fadhili William’s phone number in the United States, explaining that William had moved there some years earlier, pursuing royalties for his world-famous song, “Malaika,” and was currently working in a gas station in New Jersey. When I left school in 1959, that’s the time I composed “Malaika.” When I was in school I had a girlfriend, to me she looked like an angel. Her name was Fanny, but I nicknamed her Malaika. I wanted to get married to her, but you had to pay dowry to get married and I didn’t have that kind of money. So she was married by somebody else who had the dowry, the parents. Now, the only thing I could make her remember me is by playing that song. Even though there was her husband at home, listening to the radio, she could hear that song, because she knows her nickname, and the husband won’t know who is this Malaika, to portray that message to her that I still love her.

When I left school in 1959, that’s the time I composed “Malaika.” When I was in school I had a girlfriend, to me she looked like an angel. Her name was Fanny, but I nicknamed her Malaika. I wanted to get married to her, but you had to pay dowry to get married and I didn’t have that kind of money. So she was married by somebody else who had the dowry, the parents. Now, the only thing I could make her remember me is by playing that song. Even though there was her husband at home, listening to the radio, she could hear that song, because she knows her nickname, and the husband won’t know who is this Malaika, to portray that message to her that I still love her. in Antwerp in the summer of 1979, staying with a guy named Marc who played terrific guitar using just his thumb and middle finger — I have no idea why he didn’t use his index finger, but he didn’t — and he had Doc Watson’s recording and I learned a half-assed version of it.

in Antwerp in the summer of 1979, staying with a guy named Marc who played terrific guitar using just his thumb and middle finger — I have no idea why he didn’t use his index finger, but he didn’t — and he had Doc Watson’s recording and I learned a half-assed version of it. The only other Loudermilk composition I ever learned is a teen novelty song “Norman,” which was a hit for Sue Thompson in 1961 (which I see is also when Atkins recorded W&W). I probably learned “Norman” as a joke when I was in my teens, and almost fifty years later I’m still stuck with it:

The only other Loudermilk composition I ever learned is a teen novelty song “Norman,” which was a hit for Sue Thompson in 1961 (which I see is also when Atkins recorded W&W). I probably learned “Norman” as a joke when I was in my teens, and almost fifty years later I’m still stuck with it: It All My Days” to show how Hurt used the same fifth position partial D chord in both, with somewhat different effects. As it happens, I then started using the riff from this song in the breaks of Hurt’s “

It All My Days” to show how Hurt used the same fifth position partial D chord in both, with somewhat different effects. As it happens, I then started using the riff from this song in the breaks of Hurt’s “ At least that’s my take, and I made John Hurt my first test case, learning a couple of dozen of his pieces and assuming that when something felt uncomfortable I was doing it wrong. In the process, I learned a lot of songs I had passed over in the past, including this one. I learned this as an exercise, and the more I played it, the more I loved it. I like the way the lyric limns a story in short phrases, I like the quirky additional measure in the E section — and, most of all, I love the way it feels. Once I got my hands to do what his hands did, it felt like walking down a well-worn path — not working to sound like him, just ambling along in his footsteps

At least that’s my take, and I made John Hurt my first test case, learning a couple of dozen of his pieces and assuming that when something felt uncomfortable I was doing it wrong. In the process, I learned a lot of songs I had passed over in the past, including this one. I learned this as an exercise, and the more I played it, the more I loved it. I like the way the lyric limns a story in short phrases, I like the quirky additional measure in the E section — and, most of all, I love the way it feels. Once I got my hands to do what his hands did, it felt like walking down a well-worn path — not working to sound like him, just ambling along in his footsteps