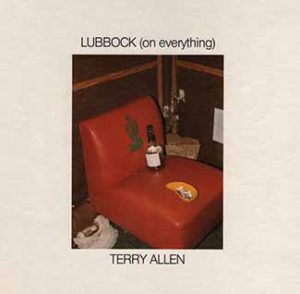

Terry Allen’s masterpiece of corrosive American dreaming, from his Lubbock (On Everything) LP. I’ve written in a previous post about my discovery of Allen’s work, but at  first I thought of him as a quirky novelty writer and it took a couple of years before I immersed myself in that album. Thirty years later, it’s still a relatively little-known (though widely acknowledged) classic, and anyone who hasn’t heard it should just go out and buy a copy.

first I thought of him as a quirky novelty writer and it took a couple of years before I immersed myself in that album. Thirty years later, it’s still a relatively little-known (though widely acknowledged) classic, and anyone who hasn’t heard it should just go out and buy a copy.

This song is Allen at his best, sketching simple lines that evoke the power and pitfalls of the romantic myths that underpin much of my life and the music I love. It opens on a stretch of western highway familiar from a million movies, the “blue asphaltum line,” beloved of James Dean and Chuck Berry, Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady, Thelma and Louise. The soundtrack is late-night radio, blasting across the Texas-Mexico border on the 250,000 watts of XERF, 1570-AM, punctuated by the dark growl of the midnight master, the Wolfman of Del Rio.

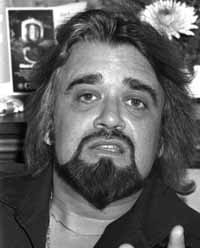

By the time I first heard Wolfman Jack, he was a chubby self-parody cruising through a second career courtesy of American Graffiti, so it took a while for me to connect him with the werevoice haunting Allen’s song. But it was the same guy. Born Robert Smith in Brooklyn, reborn as the Wolfman in Shreveport, he began  broadcasting over XERF in 1963 and in the early years concealed his identity, refusing interviews and photographs. Station promos showed a drawing of a hip wolf, or photographs of a hirsute face of uncertain ethnicity, eyes hidden behind dark shades. He broadcast from midnight till 4am, and could be

broadcasting over XERF in 1963 and in the early years concealed his identity, refusing interviews and photographs. Station promos showed a drawing of a hip wolf, or photographs of a hirsute face of uncertain ethnicity, eyes hidden behind dark shades. He broadcast from midnight till 4am, and could be  heard all over the Central and Western United States, and sometimes as far away as Europe. He played current hits, deep blues, grinding R&B, howled along with favorite records, sometimes called a lady friend live on the air, and was worshiped by millions of teenagers as a mysterious creature of the night.

heard all over the Central and Western United States, and sometimes as far away as Europe. He played current hits, deep blues, grinding R&B, howled along with favorite records, sometimes called a lady friend live on the air, and was worshiped by millions of teenagers as a mysterious creature of the night.

It is hard for those of us who came along later and were introduced to Jack and that music as nostalgic “oldies” to imagine how they sounded and what they meant to millions of listeners who heard them as the sound of a wild new world, of infinite possibilities, of escape from dead-end towns and dead-end lives.

But it is all too easy to recognize the hangover: a world of people raised on those fantasies, yearning to be daring individualists but trapped in the decaying badlands of late industrial capitalism, fighting to hold onto poisoned dreams. That’s the theme of Allen’s song, and it’s one of my favorites.

Years after I learned this, I was working on a project called River of Song with a sound crew from the Smithsonian, and one of the guys had recently finished a project about early R&B radio. One of the guys they’d planned to interview was Wolfman Jack, and he showed up at the studio ready to talk. So, they asked him, “How did you come up with your Wolfman persona?”

“It was kind of a Lord Buckley thing,” he replied.

“Who was Lord Buckley?” asked the interviewer.

“You never heard of Lord Buckley?”

The interviewer shook his head.

“Then we got nothing to talk about,” the Wolfman said, and walked out.