I spent a month or so hitchhiking around Scotland in the summer of 1989, partly because I was headed to Africa and wanted to familiarize myself with the work of Jim Reeves. I’d heard that Reeves was hugely popular in both places, but all I knew of his music was this song, which I’d learned off a Ry Cooder album. So I figured I should know more, and Scotland was the place to go.

That proved to be theoretically but not practically right: Reeves was indeed popular in Scottish country-western bars, but I got distracted and ended up visiting castles, hitchhiking north to Orkney, and sleeping in stone circles rather than learning his music. I also spent a pleasant few days visiting Belle and Sheila Stewart, the great Scots traditional singers, but their tastes in country ran more to Hank Williams.

So I fell back on the Cooder version, which fitted well with my plans to study African guitar, because he played it in a sort of Caribbean rumba rhythm.

That was probably the high point of my interest in Cooder, and I have to say it was always more interest than love. I loved the idea of his albums, especially in the Chicken Skin Music period when he was mixing odd assemblages of musicians from disparate traditions and choosing unlikely material to do with them. That was my first taste of Hawaiian slack-key guitar, and also my reintroduction to Flaco Jimenez, whom I’d first heard on my treasured Doug Sahm and Band album. Flaco played on this song, and Bobby King was singing gospel back-up, and it was a really nice arrangement… but there was something kind of emotionally flat about it. I listened to those albums a bunch of times and recall them with appreciation, but my heart is with other stuff.

That was probably the high point of my interest in Cooder, and I have to say it was always more interest than love. I loved the idea of his albums, especially in the Chicken Skin Music period when he was mixing odd assemblages of musicians from disparate traditions and choosing unlikely material to do with them. That was my first taste of Hawaiian slack-key guitar, and also my reintroduction to Flaco Jimenez, whom I’d first heard on my treasured Doug Sahm and Band album. Flaco played on this song, and Bobby King was singing gospel back-up, and it was a really nice arrangement… but there was something kind of emotionally flat about it. I listened to those albums a bunch of times and recall them with appreciation, but my heart is with other stuff.

As for Jim Reeves, I clearly listened to his version of this, since I just checked and find I sing his lyrics rather than Cooder’s variant, as well as that great low note (which he sings gorgeously and I attempt with infinite pleasure). But I don’t recall any of his other  songs, which just proves how out of step I am with a lot of parts of the world, because for a lot of people Reeves was the greatest singer the US ever produced, and they live in some surprising places. For instance Norway, Kenya, South Africa, and India… and I’ve got a story about that:

songs, which just proves how out of step I am with a lot of parts of the world, because for a lot of people Reeves was the greatest singer the US ever produced, and they live in some surprising places. For instance Norway, Kenya, South Africa, and India… and I’ve got a story about that:

In 1981 I was hitchhiking from Bombay (now Mumbai) to Madras (now Chennai), and somewhere out in the middle of nowhere I got stranded and was walking along a hot, dusty road beginning to wonder where I’d get some water. Eventually I saw a little village, but it was just a cluster of houses and a bit off the road, so I was debating whether to go over, and then a little boy came running out to me. I had my guitar slung over my shoulder, and he’d spotted it and said I had to come meet his father. So I went along with him, and his father invited me into their house and gave me a cup of tea. Then he proudly showed me his record collection: it consisted of pretty much every record Jim Reeves had made, and nothing else.

So that’s that. Wherever I went in Africa, I played this song, and people always recognized and enjoyed it, though by the late 1980s the fave was Don Williams. They like pretty singers over there.

Oh, and one more thing… I went to Africa in a large part to learn how to fingerpick these kinds of rhythms, and I’m very happy with how that worked out, and how nicely that style fits songs like this.

People have often asked if I was really able to make a living that way, and the honest answer is I’ve never lived better than during that period in Antwerp. I was staying in my girlfriend Miet’s apartment, paying some utilities and buying food, but I think she covered most if not all of the rent, which in any case was low. I could make the equivalent of about ten dollars per terrace, which took about fifteen minutes, and on a sunny weekend I could go across the Schelde to the cluster of cafes on the other side and often made two or three hundred dollars. If I felt like working some more, I could do the restaurants and bars in the evening, but after I came up with a regular terrace circuit I usually took the evenings off.

People have often asked if I was really able to make a living that way, and the honest answer is I’ve never lived better than during that period in Antwerp. I was staying in my girlfriend Miet’s apartment, paying some utilities and buying food, but I think she covered most if not all of the rent, which in any case was low. I could make the equivalent of about ten dollars per terrace, which took about fifteen minutes, and on a sunny weekend I could go across the Schelde to the cluster of cafes on the other side and often made two or three hundred dollars. If I felt like working some more, I could do the restaurants and bars in the evening, but after I came up with a regular terrace circuit I usually took the evenings off. I was doing a lot of traveling as well, because it was easy — wherever I went, I could make food money with my guitar, there were always people ready to provide a bed or couch, and the Antwerp earnings provided a cushion. I hitched up to the north of Scotland and caught a ferry to Orkney, hitched down through Italy and caught a ferry to Tunisia (I remember reading Tom Jones on that trip), and rambled through Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey with my buddy Jasper (I was reading Piers Plowman, or rather not reading it, because that one was unreadable — and also impossible to trade away once I gave up).

I was doing a lot of traveling as well, because it was easy — wherever I went, I could make food money with my guitar, there were always people ready to provide a bed or couch, and the Antwerp earnings provided a cushion. I hitched up to the north of Scotland and caught a ferry to Orkney, hitched down through Italy and caught a ferry to Tunisia (I remember reading Tom Jones on that trip), and rambled through Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey with my buddy Jasper (I was reading Piers Plowman, or rather not reading it, because that one was unreadable — and also impossible to trade away once I gave up). liked his painting, never went in, but the terraces were great for busking and there was a good used bookstore next door) and an easy walk to the cafes by the central station in one direction and the cafes near the Groenplaats in the other.

liked his painting, never went in, but the terraces were great for busking and there was a good used bookstore next door) and an easy walk to the cafes by the central station in one direction and the cafes near the Groenplaats in the other. except a lot of that material is sexual or misogynist, while this is just brutally realistic, matching its language to the setting and circumstance. (Which is to say: WARNING! Raw language ahead.)

except a lot of that material is sexual or misogynist, while this is just brutally realistic, matching its language to the setting and circumstance. (Which is to say: WARNING! Raw language ahead.) traveling that way, which didn’t work out, but we did visit a bunch of cowboys out on the

traveling that way, which didn’t work out, but we did visit a bunch of cowboys out on the  So anyway, we were talking about horses a lot, which reminded me of this song, and I sang it for Jasper, and he declared it the most realistic cowboy song he’d ever heard, which was good enough for me. (He went on to spend years traveling to horse cultures around the world, riding and writing about them, and I wish he’d do a book about those adventures. Instead, he’s been doing books on

So anyway, we were talking about horses a lot, which reminded me of this song, and I sang it for Jasper, and he declared it the most realistic cowboy song he’d ever heard, which was good enough for me. (He went on to spend years traveling to horse cultures around the world, riding and writing about them, and I wish he’d do a book about those adventures. Instead, he’s been doing books on  In his anthology of cowboy lyrics, The Whorehouse Bells Were Ringing, Guy Logsdon explains that Fletcher wrote the original poem in 1914 and although he was known for writing dirty parodies of his own songs, no one recalls hearing this one until the 1940s. Before that he was apparently doing a different parody, a sixteen-verse saga that graphically reworked the original theme of a cowboy confronting a particularly vicious horse, ending:

In his anthology of cowboy lyrics, The Whorehouse Bells Were Ringing, Guy Logsdon explains that Fletcher wrote the original poem in 1914 and although he was known for writing dirty parodies of his own songs, no one recalls hearing this one until the 1940s. Before that he was apparently doing a different parody, a sixteen-verse saga that graphically reworked the original theme of a cowboy confronting a particularly vicious horse, ending:

One piece I worked on that winter was Tommy Johnson’s “Big Road Blues,” or at least my approximation of it. I always loved Johnson’s singing, and at times have named him as my favorite of the classic Delta blues guitarists in the circle around Charlie Patton. His music has a lightness I don’t hear in other Delta players, while retaining the rhythmic complexity and emotional depth.

One piece I worked on that winter was Tommy Johnson’s “Big Road Blues,” or at least my approximation of it. I always loved Johnson’s singing, and at times have named him as my favorite of the classic Delta blues guitarists in the circle around Charlie Patton. His music has a lightness I don’t hear in other Delta players, while retaining the rhythmic complexity and emotional depth. There was also a spectacular version on Yazoo’s Jackson Blues anthology, by an obscure Delta musician named Willie Lofton who called it “Dark Road Blues” and out-did Johnson at Johnson’s own style, playing with ferocious speed and power and punctuating his vocal lines with a gorgeous falsetto.

There was also a spectacular version on Yazoo’s Jackson Blues anthology, by an obscure Delta musician named Willie Lofton who called it “Dark Road Blues” and out-did Johnson at Johnson’s own style, playing with ferocious speed and power and punctuating his vocal lines with a gorgeous falsetto. the years, and one year he brought him to my place in Cambridge for dinner. At that point I was dating a woman who played concert harp, and my fondest memory of that evening is Brewer seated at her harp, exploring its possibilities and eventually picking out some gospel tunes. Later we got out guitars, and he played a blazing version of “Big Road,” using a technique I’ve never seen before or since: where I (like everyone else) snap the low 6th string, he reached into the soundhole with his thumb and snapped the 5th and 6th, in that order, in a roll with the 4th picked by his index finger. I tried and tried, but can’t get that move up to any kind of speed — when he did it, it was like a drum-roll, and the power was incredible.

the years, and one year he brought him to my place in Cambridge for dinner. At that point I was dating a woman who played concert harp, and my fondest memory of that evening is Brewer seated at her harp, exploring its possibilities and eventually picking out some gospel tunes. Later we got out guitars, and he played a blazing version of “Big Road,” using a technique I’ve never seen before or since: where I (like everyone else) snap the low 6th string, he reached into the soundhole with his thumb and snapped the 5th and 6th, in that order, in a roll with the 4th picked by his index finger. I tried and tried, but can’t get that move up to any kind of speed — when he did it, it was like a drum-roll, and the power was incredible. I also played it pretty regularly during my 1987-88 winter residency in Sevilla, Spain — unquestionably my hardest-working period as a blues player. I was in Sevilla with some friends from Antwerp, Vera Singelyn,

I also played it pretty regularly during my 1987-88 winter residency in Sevilla, Spain — unquestionably my hardest-working period as a blues player. I was in Sevilla with some friends from Antwerp, Vera Singelyn,  Tuesday in another, and so on. He’d also named us the Mississippi Sheiks, which felt weird to me since I’d never been in Mississippi and that name was already taken by one of the great groups of the 1920s… but Juan liked it, and he was the boss.

Tuesday in another, and so on. He’d also named us the Mississippi Sheiks, which felt weird to me since I’d never been in Mississippi and that name was already taken by one of the great groups of the 1920s… but Juan liked it, and he was the boss. the 1970s called La Pata Negra, mixing flamenco with Jeff Beck-style electric leads. (For a taste, check out their “

the 1970s called La Pata Negra, mixing flamenco with Jeff Beck-style electric leads. (For a taste, check out their “ As for the Seaboard railroad lines, they were part of a network that reached down to Florida, over to New Orleans, and up to New York. In The Warmth of Other Suns, Isabel Wilkerson writes about the Seaboard as one of the main engines of the Great Migration, which adds another dimension to the song.

As for the Seaboard railroad lines, they were part of a network that reached down to Florida, over to New Orleans, and up to New York. In The Warmth of Other Suns, Isabel Wilkerson writes about the Seaboard as one of the main engines of the Great Migration, which adds another dimension to the song. In the mid 1980s Vera Singelyn was running a place in Antwerp that provided cheap rooms and dinners for street people and buskers, and she had a four-month-old son, Liam. He was a pretty tranquil kid but one evening he started crying just as she was trying to dish out food for a couple of dozen people, so I picked him up and bounced him, and when he kept crying I asked Vera if I could carry him around the block…

In the mid 1980s Vera Singelyn was running a place in Antwerp that provided cheap rooms and dinners for street people and buskers, and she had a four-month-old son, Liam. He was a pretty tranquil kid but one evening he started crying just as she was trying to dish out food for a couple of dozen people, so I picked him up and bounced him, and when he kept crying I asked Vera if I could carry him around the block… That was also where Liam made his debut as a clown — by then, he knew that when Vera put on make-up she would be going out, so he would start screaming, and that afternoon we dealt with the situation by making him up as well and bringing him along. I waited till Vera had a crowd around her, then released him, and he ran over to her hat, picked it up, carried it around the circle, and made a small fortune in coins… then went back to the center of the circle, dumped the coins on the ground, picked up two handfuls, and started distributing them to the other children in the crowd.

That was also where Liam made his debut as a clown — by then, he knew that when Vera put on make-up she would be going out, so he would start screaming, and that afternoon we dealt with the situation by making him up as well and bringing him along. I waited till Vera had a crowd around her, then released him, and he ran over to her hat, picked it up, carried it around the circle, and made a small fortune in coins… then went back to the center of the circle, dumped the coins on the ground, picked up two handfuls, and started distributing them to the other children in the crowd. at the Caffe Lena in Saratoga, and he stayed with me whenever he was in Cambridge, and I stayed with him in Spokane and later in Grass Valley. He was genuinely a gentleman and a scholar, and one of his fields of scholarship was the old west. This song was inspired by the name of one of the main cattle trails out of Texas, pioneered by Charlie Goodnight and Oliver Loving in the 1860s, which went up through New Mexico to Colorado and eventually Wyoming.

at the Caffe Lena in Saratoga, and he stayed with me whenever he was in Cambridge, and I stayed with him in Spokane and later in Grass Valley. He was genuinely a gentleman and a scholar, and one of his fields of scholarship was the old west. This song was inspired by the name of one of the main cattle trails out of Texas, pioneered by Charlie Goodnight and Oliver Loving in the 1860s, which went up through New Mexico to Colorado and eventually Wyoming. ago, I had the pleasure of watching a salesman marketing aceite de vibora.

ago, I had the pleasure of watching a salesman marketing aceite de vibora. soup kitchen that was a dinner stop and occasional lodging for much of the itinerant musical population. I don’t remember how I first met Vera, but it was probably at Den Billekletser, because that was where a lot of us called home during the daytimes. It was a bar on the Hoogstraat, near the banks of cafes surrounding the Cathedral, and we would start drinking coffee there in the morning, graduate to beer around noon, and continue through the evening between sorties to play the cafes, restaurants, and bars. Some people got their mail delivered there, and for ten years or so I would go there first whenever I hit town and find out who else was around and where they were living.

soup kitchen that was a dinner stop and occasional lodging for much of the itinerant musical population. I don’t remember how I first met Vera, but it was probably at Den Billekletser, because that was where a lot of us called home during the daytimes. It was a bar on the Hoogstraat, near the banks of cafes surrounding the Cathedral, and we would start drinking coffee there in the morning, graduate to beer around noon, and continue through the evening between sorties to play the cafes, restaurants, and bars. Some people got their mail delivered there, and for ten years or so I would go there first whenever I hit town and find out who else was around and where they were living. It’s also possible that I met Vera at the Musik Doos, which was in a couple of different locations over the years and had a stage and microphones for whoever wanted to play a set and pass the hat. Etienne, the owner, was always good to me and I made a lot of friends there. Or maybe someone just brought me over to the place Vera was running to have some dinner.

It’s also possible that I met Vera at the Musik Doos, which was in a couple of different locations over the years and had a stage and microphones for whoever wanted to play a set and pass the hat. Etienne, the owner, was always good to me and I made a lot of friends there. Or maybe someone just brought me over to the place Vera was running to have some dinner. waifs and wastrels, and shortly she was letting me live in an apartment on the third floor of a house she had at Huikstraat 5, in the red light district. As I recall, Irish Tony and Jimmy were on the second floor, and Montana Bob and his daughter were on the fourth – or maybe Bob and his daughter had the other side of the third and

waifs and wastrels, and shortly she was letting me live in an apartment on the third floor of a house she had at Huikstraat 5, in the red light district. As I recall, Irish Tony and Jimmy were on the second floor, and Montana Bob and his daughter were on the fourth – or maybe Bob and his daughter had the other side of the third and  terraces in the daytime, and then Nick and I would get together and do the nice restaurants. We’d typically warm up by playing a standard in all twelve keys, and “Some of These Days” was one of our favorites, along with “

terraces in the daytime, and then Nick and I would get together and do the nice restaurants. We’d typically warm up by playing a standard in all twelve keys, and “Some of These Days” was one of our favorites, along with “ great new introductory verse, and that got me singing it again, usually with my wife Sandrine on clarinet. Now I need to get back to Antwerp and try it again with Nick, whom I haven’t played with in almost thirty years — but see

great new introductory verse, and that got me singing it again, usually with my wife Sandrine on clarinet. Now I need to get back to Antwerp and try it again with Nick, whom I haven’t played with in almost thirty years — but see  rarer on the busking scene. So I hit Paris, dropped in at

rarer on the busking scene. So I hit Paris, dropped in at  didn’t allow buskers. We’d go in and ask if we could play, and they’d say no, and we’d make a deal: we’d do one song, and if they didn’t want to hear another we’d leave without bothering the customers for money. So they’d grumble a bit, but give us a chance….

didn’t allow buskers. We’d go in and ask if we could play, and they’d say no, and we’d make a deal: we’d do one song, and if they didn’t want to hear another we’d leave without bothering the customers for money. So they’d grumble a bit, but give us a chance…. None of which connects directly to “Hello, Mary Lou,” except that I was working on my rock ‘n’ roll oldies repertoire and when I went out alone I played this as well as the Everly and Holly songs, and had a nicer guitar arrangement for it. I learned it off a record by Gene Pitney, which I picked up at a yard sale for next to nothing back in my teens — the hit version was by Ricky Nelson, but Pitney wrote it and I liked his version. It wasn’t as fancy as “Town without Pity” or “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” but more fun.

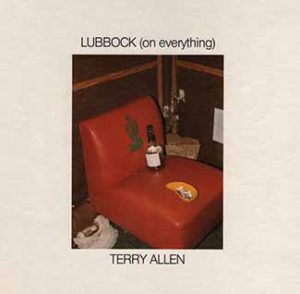

None of which connects directly to “Hello, Mary Lou,” except that I was working on my rock ‘n’ roll oldies repertoire and when I went out alone I played this as well as the Everly and Holly songs, and had a nicer guitar arrangement for it. I learned it off a record by Gene Pitney, which I picked up at a yard sale for next to nothing back in my teens — the hit version was by Ricky Nelson, but Pitney wrote it and I liked his version. It wasn’t as fancy as “Town without Pity” or “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” but more fun. first I thought of him as a quirky novelty writer and it took a couple of years before I immersed myself in that album. Thirty years later, it’s still a relatively little-known (though widely acknowledged) classic, and anyone who hasn’t heard it should just go out and buy a copy.

first I thought of him as a quirky novelty writer and it took a couple of years before I immersed myself in that album. Thirty years later, it’s still a relatively little-known (though widely acknowledged) classic, and anyone who hasn’t heard it should just go out and buy a copy. broadcasting over XERF in 1963 and in the early years concealed his identity, refusing interviews and photographs. Station promos showed a drawing of a hip wolf, or photographs of a hirsute face of uncertain ethnicity, eyes hidden behind dark shades. He broadcast from midnight till 4am, and could be

broadcasting over XERF in 1963 and in the early years concealed his identity, refusing interviews and photographs. Station promos showed a drawing of a hip wolf, or photographs of a hirsute face of uncertain ethnicity, eyes hidden behind dark shades. He broadcast from midnight till 4am, and could be  heard all over the Central and Western United States, and sometimes as far away as Europe. He played current hits, deep blues, grinding R&B, howled along with favorite records, sometimes called a lady friend live on the air, and was worshiped by millions of teenagers as a mysterious creature of the night.

heard all over the Central and Western United States, and sometimes as far away as Europe. He played current hits, deep blues, grinding R&B, howled along with favorite records, sometimes called a lady friend live on the air, and was worshiped by millions of teenagers as a mysterious creature of the night.