When I was maybe six years old, my parents bought me a little portable record player. It was about a foot square, closed up like a suitcase, and had four speeds: 1 6, 33 1/3, 45, and 78. They wouldn’t let me play their records on it, but I had a few children’s folk LPs — one by Tom Glazer, and a couple of Everybody Sing! anthologies — and somehow I also ended up with my grandparents’ 78 albums.

6, 33 1/3, 45, and 78. They wouldn’t let me play their records on it, but I had a few children’s folk LPs — one by Tom Glazer, and a couple of Everybody Sing! anthologies — and somehow I also ended up with my grandparents’ 78 albums.

My mother’s family were refugees from Nazi Vienna and old-line Communists — till the day he died, my grandfather had the complete works of Marx, Lenin, and Stalin in his home office, in German. (Also the complete works of Joseph Conrad, Jack London, and Mark Twain.) I don’t think they were politically active after coming to the United States,  but along with dozens of classical albums, they had the classic Communist record collection of the early 1940s: Paul Robeson, the Red Army Chorus, the International Brigades from the Spanish Civil War, Josh White, the Almanac Singers, and the Union Boys. The Union Boys wasn’t actually a group — it was just a bunch of singers who got together to record an album’s worth of songs about union organizing and the war effort, among them Pete Seeger, Burl Ives, Tom Glazer, Josh White, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, plus one side by Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston.

but along with dozens of classical albums, they had the classic Communist record collection of the early 1940s: Paul Robeson, the Red Army Chorus, the International Brigades from the Spanish Civil War, Josh White, the Almanac Singers, and the Union Boys. The Union Boys wasn’t actually a group — it was just a bunch of singers who got together to record an album’s worth of songs about union organizing and the war effort, among them Pete Seeger, Burl Ives, Tom Glazer, Josh White, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, plus one side by Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston.

I played those records constantly and learned most of the songs, and these two were particular favorites. I suppose part of the appeal was the war — despite my parents’ pacifist leanings, I played with toy soldiers and dug trenches and all that kind of stuff, and it was exciting to sing about rolling into Berlin with your buddies from the union and going after Hitler. I didn’t understand all the words, of course — I don’t think I knew the meaning of either UAW or CIO — but thirty years later, when I helped organize a freelancer’s group at the Boston Globe under the auspices of the National Writers Union, I was particularly pleased that we were a subsection of the UAW. It kind of brought everything full circle, and felt like I’d stayed true to my early friends.

I played those records constantly and learned most of the songs, and these two were particular favorites. I suppose part of the appeal was the war — despite my parents’ pacifist leanings, I played with toy soldiers and dug trenches and all that kind of stuff, and it was exciting to sing about rolling into Berlin with your buddies from the union and going after Hitler. I didn’t understand all the words, of course — I don’t think I knew the meaning of either UAW or CIO — but thirty years later, when I helped organize a freelancer’s group at the Boston Globe under the auspices of the National Writers Union, I was particularly pleased that we were a subsection of the UAW. It kind of brought everything full circle, and felt like I’d stayed true to my early friends.

The title song was his own composition–he was always trying to come up with new approaches to old blues styles, and this is a perfect example: the humor and language are a mix of his modern sensibility and the kind of street lingo he enjoyed in songs and books from earlier eras, in keeping with the tastes of a man who named his rock band the Hudson Dusters after one of the Irish street gangs in Herbert Asbury’s Gangs of New York. For example, to be in tap city is an extension of “tapping out,” or going broke at poker.

The title song was his own composition–he was always trying to come up with new approaches to old blues styles, and this is a perfect example: the humor and language are a mix of his modern sensibility and the kind of street lingo he enjoyed in songs and books from earlier eras, in keeping with the tastes of a man who named his rock band the Hudson Dusters after one of the Irish street gangs in Herbert Asbury’s Gangs of New York. For example, to be in tap city is an extension of “tapping out,” or going broke at poker. so I settled for playing a couple of Johnson’s pieces, with some licks from Son House, who seems to have been the main source for his slide style, and this is the one that stuck with me.

so I settled for playing a couple of Johnson’s pieces, with some licks from Son House, who seems to have been the main source for his slide style, and this is the one that stuck with me.

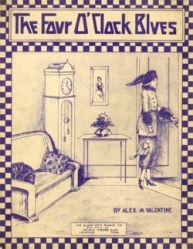

Which said, Dunn’s recording is an instrumental, and the published sheet music has lyrics that bear no resemblance to what Johnson sang… and the song was also published in Memphis around that time with credit to another composer, Alex Valentine… and Skip James recorded a version of the song as “Four O’Clock Blues,” before Johnson did it, with yet another set of lyrics… and Alan Lomax recorded yet another version of the song in 1941 from Son House, Willie Brown, and Fiddlin’ Joe Martin, who could have been Johnson’s source…

Which said, Dunn’s recording is an instrumental, and the published sheet music has lyrics that bear no resemblance to what Johnson sang… and the song was also published in Memphis around that time with credit to another composer, Alex Valentine… and Skip James recorded a version of the song as “Four O’Clock Blues,” before Johnson did it, with yet another set of lyrics… and Alan Lomax recorded yet another version of the song in 1941 from Son House, Willie Brown, and Fiddlin’ Joe Martin, who could have been Johnson’s source…

of jazz, blues, international and other LPs, and that was where I first heard Jean-Bosco Mwenda’s playing, on an LP called Guitars of Africa. Like everyone else who heard that record, I was blown away by his instrumental version of Masanga, and fortunately both Pete Seeger and Happy Traum had published tablature for it, so I managed to cobble together a half-assed version.

of jazz, blues, international and other LPs, and that was where I first heard Jean-Bosco Mwenda’s playing, on an LP called Guitars of Africa. Like everyone else who heard that record, I was blown away by his instrumental version of Masanga, and fortunately both Pete Seeger and Happy Traum had published tablature for it, so I managed to cobble together a half-assed version. recall, Tracey’s notes said that Bosco was in his late teens when he made the recording, circa 1951, and had only been playing for a couple of years–which seemed incredible, but he was a pretty incredible person. (Though, to be fair, he told me a different story when I

recall, Tracey’s notes said that Bosco was in his late teens when he made the recording, circa 1951, and had only been playing for a couple of years–which seemed incredible, but he was a pretty incredible person. (Though, to be fair, he told me a different story when I

Woody Guthrie is still one of my favorite players and singers–I like his songwriting too, but he gets plenty of credit for that elsewhere, and his musicianship tends to be underrated. On his record of this song, the title is given as “Baltimore to Washington,” and I’ve also seen it as “The Cannonball.”

Woody Guthrie is still one of my favorite players and singers–I like his songwriting too, but he gets plenty of credit for that elsewhere, and his musicianship tends to be underrated. On his record of this song, the title is given as “Baltimore to Washington,” and I’ve also seen it as “The Cannonball.” …Brownie was mentored as a young musician by a guitarist and singer named Leslie Riddle, who is best known for traveling around the South gathering songs with A.P. Carter and teaching Maybelle Carter how to fingerpick. As she explained:

…Brownie was mentored as a young musician by a guitarist and singer named Leslie Riddle, who is best known for traveling around the South gathering songs with A.P. Carter and teaching Maybelle Carter how to fingerpick. As she explained: And as it happens, one of the songs they learned from Riddle was “Cannonball Blues,” including the guitar part that Woody got from Maybelle and I got from Woody. As Sara said, “That’s kind of the way he picked it… [Maybelle] kind of caught some of her style from him, for that one, especially.”

And as it happens, one of the songs they learned from Riddle was “Cannonball Blues,” including the guitar part that Woody got from Maybelle and I got from Woody. As Sara said, “That’s kind of the way he picked it… [Maybelle] kind of caught some of her style from him, for that one, especially.”