The Confidential Guide published by the The Harvard Crimson and based on questionnaires filled out by students, had this to say about the introductory biology course my father taught for decades: “Nat Sci 5 has turned more scientists into poets, and more poets into scientists, than any course ever taught on this campus.”

One

project of mine that has not yet reached fruition is a biography or autobiography

of my father, George Wald. In the late 1980s, I taped his memoirs, and have

twice tried to work this material up into a book, but wiser heads have informed

me that it is not publishable in its current state. I still intend to find a way to get this material into the world, though, as I believe

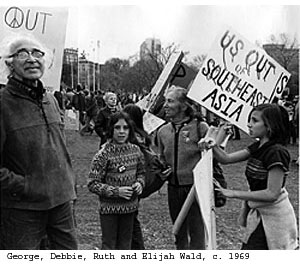

my father to have been a quite extraordinary man. He was known first as

a biologist, one of the century's foremost investigators of the biochemistry

of vision, and won a Nobel Prize for this work in 1967. (For more information

on this aspect of my father's life, I strongly recommend the warm and thorough

remembrance

by his longtime friend and colleague John Dowling.) I was eight years

old at that time, and recall it well, but for most of my life he was less

involved in science than in political activism, a change that happened shortly

after receiving the prize, when he used the forum this fame gave him to

voice his opposition to the war in Vietnam, and the militarization of American

life. His new career began literally overnight, when he gave a speech at

MIT that was shortly translated into over forty languages, reprinted millions

of times, and even made into a record album. (To read this speech, go to

A Generation in Search of a Future.)

intend to find a way to get this material into the world, though, as I believe

my father to have been a quite extraordinary man. He was known first as

a biologist, one of the century's foremost investigators of the biochemistry

of vision, and won a Nobel Prize for this work in 1967. (For more information

on this aspect of my father's life, I strongly recommend the warm and thorough

remembrance

by his longtime friend and colleague John Dowling.) I was eight years

old at that time, and recall it well, but for most of my life he was less

involved in science than in political activism, a change that happened shortly

after receiving the prize, when he used the forum this fame gave him to

voice his opposition to the war in Vietnam, and the militarization of American

life. His new career began literally overnight, when he gave a speech at

MIT that was shortly translated into over forty languages, reprinted millions

of times, and even made into a record album. (To read this speech, go to

A Generation in Search of a Future.)

I

also want to include the stories that I loved as a child, most of them

about his life in Brooklyn, or his summers "shipping out" to

Europe or South America. These tales were full of the same searching curiosity

that fueled his scientific investigations, but revealed a very different

person, and that was the man I thought of as my father. When I took off

on the road as a musician, hitch-hiking across three continents, people

always asked me why or how I had turned out so differently from my father,

but the fact is that I was inspired as much by his tales of hitch-hiking

to Canada or working on a freighter to Buenos Aires, or of the vaudeville

act he did with a friend when they were in their teens, as I was by reading

Woody Guthrie's "Bound for Glory."

I

also want to include the stories that I loved as a child, most of them

about his life in Brooklyn, or his summers "shipping out" to

Europe or South America. These tales were full of the same searching curiosity

that fueled his scientific investigations, but revealed a very different

person, and that was the man I thought of as my father. When I took off

on the road as a musician, hitch-hiking across three continents, people

always asked me why or how I had turned out so differently from my father,

but the fact is that I was inspired as much by his tales of hitch-hiking

to Canada or working on a freighter to Buenos Aires, or of the vaudeville

act he did with a friend when they were in their teens, as I was by reading

Woody Guthrie's "Bound for Glory."

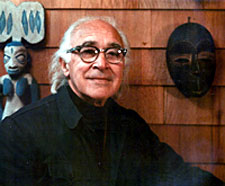

In any case, I still intend to do this book someday, and any publishers reading this page are encouraged to contact me if interested.... but in the meanwhile, I wanted to put up a few scraps that for one reason or another I enjoy having out in the world.

For

example, this is his college yearbook picture, from Washington Square College

of New York University, in 1927. The caption next to it said:

For

example, this is his college yearbook picture, from Washington Square College

of New York University, in 1927. The caption next to it said:

“Ah, but what a gesture!” So spoke Cyrano in answer to his friend’s protest after he had thrown his last bit of gold to the actors. So said George after he bought that walking stick, automatically foregoing meals for a week. By the end of the seven days he was so weak from starvation that the cane was no longer a luxury, but a necessity to support his tottering frame to and from the college. George has a weakness for beauty, golden bucks served in Greek restaurants, rooms in the village, complimentary tickets and Christian Science Monitor dramatic critics. He is well-traveled, having been as far north as the Bronx, as far west as Staten Island and as far south as South America, where he went last summer by rail. (No, not that kind of rail.) You must get him to tell you of his delightful adventures in the land of chili con carne and dark complexions. Don’t be afraid if he should suddenly develop an acute Jewish accent while talking to you. It simply means that he is just beginning the infamous “foozball” story. It seems that there are two people in W. S. C. who have not yet heard it, and it would break our George’s heart if he graduated without being able to find and tell it to them.

Though I was born more than thirty years after those words were written, they describe exactly the person I thought of as my father. I grew up on stories about that cane, and what a ridiculous little "perp" he looked, as he jauntily flaunted it on the avenues. His days ghost-writing reviews for the Christian Science Monitor, during which he saw such performers as Houdini and the Marx Brothers, were an obvious inspiration to me. And as for the Jewish accent and the "foozball" story, that was a regular set-piece of my childhood, my father reciting and all of us waiting our cue, when he would shout: "Fah Vat? Fah Vat?" and we would holler back: "Fah Notting!!" My favorite Brooklyn recitation, though, was his Jewish dialect version of "The Face on the Barroom Floor," titled "Jake the Plumber," a piece of folklore that I have never seen in print , and for which I may now be the lone source...