This gaudy gunfighter ballad is from the singing of Cisco Houston. When I decided I would grow up to be a rambling musician, my heroes  were Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston, and if I’d had to pick one of them, it would probably have been Cisco. Part of the appeal was the warmth of his voice and the easy lope of his guitar, but more than that it was the songs: he liked songs that told stories, and he had an actor’s gift for making those stories come alive.

were Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston, and if I’d had to pick one of them, it would probably have been Cisco. Part of the appeal was the warmth of his voice and the easy lope of his guitar, but more than that it was the songs: he liked songs that told stories, and he had an actor’s gift for making those stories come alive.

Cisco Houston Sings American Folk Songs was my favorite album for quite a while, and I still can sing literally every song on it — not necessarily every verse, but pretty close, and I’ve posted about “St. James Infirmary,” “Midnight Special,” “ Pallet on the Floor,” “I’m Going Down the Road Feeling Bad,” “Great July Jones,” “John Hardy,” “Old Howard,” “Pat Works on the Railway,” “Rambling, Gambling Man,” and “Zebra Dun…”

Pallet on the Floor,” “I’m Going Down the Road Feeling Bad,” “Great July Jones,” “John Hardy,” “Old Howard,” “Pat Works on the Railway,” “Rambling, Gambling Man,” and “Zebra Dun…”

…but back when I was nine or ten years old, “The Killer” was my favorite. It was like a four-and-a-half-minute cowboy movie, and I remember spending an afternoon acting out the story as Cisco sang, with my best friend, Sarah Carter — I’m guessing she played Dobie Bill, since I would have wanted to do the death scene, but we may have traded off. It is also where I learned the phrase, “the vagaries of fate.”

Cisco learned this song from Katie Lee, whom I’ve talked with a few times over the years, since she was a close friend of Josh White’s,  as well as writing a good book of cowboy songs and verse, Ten Thousand Goddam Cattle, and making a bunch of recordings, and just being a hell of a fascinating person. She’s still very much around at age 95, and it’s well worth checking out her website, www.katydoodit.com, and browsing through her interviews, and film clips, and book projects.

as well as writing a good book of cowboy songs and verse, Ten Thousand Goddam Cattle, and making a bunch of recordings, and just being a hell of a fascinating person. She’s still very much around at age 95, and it’s well worth checking out her website, www.katydoodit.com, and browsing through her interviews, and film clips, and book projects.

“Talking Union” was the title song of the Almanac Singers’ most popular album (back in the days when “album” meant literally that: a bound album of 78 records). As I mentioned in the last couple of posts, my first records included a bunch of left-wing 78 albums, including Talking Union, though that one was missing its cover and I only learned what it looked like about forty years later.

“Talking Union” was the title song of the Almanac Singers’ most popular album (back in the days when “album” meant literally that: a bound album of 78 records). As I mentioned in the last couple of posts, my first records included a bunch of left-wing 78 albums, including Talking Union, though that one was missing its cover and I only learned what it looked like about forty years later.

I helped form a steering committee when we put together the Boston Globe Freelancers Association under the auspices of the National Writers Union and led a walk-out of three hundred freelance writers, photographers, and designers who refused to sign a new and confiscatory contract. I was sorry to go, because I liked writing for the Globe, but I figured that after thirty years of singing union songs it was time to step up and be counted.

I helped form a steering committee when we put together the Boston Globe Freelancers Association under the auspices of the National Writers Union and led a walk-out of three hundred freelance writers, photographers, and designers who refused to sign a new and confiscatory contract. I was sorry to go, because I liked writing for the Globe, but I figured that after thirty years of singing union songs it was time to step up and be counted. It was on the one Almanac Singers’ album my grandparents had, which I eventually learned was called Talking Union — I didn’t know the title at the time because the cover had fallen off before it came into my hands.

It was on the one Almanac Singers’ album my grandparents had, which I eventually learned was called Talking Union — I didn’t know the title at the time because the cover had fallen off before it came into my hands. Many years later, when I was researching my

Many years later, when I was researching my

6, 33 1/3, 45, and 78. They wouldn’t let me play their records on it, but I had a few children’s folk LPs — one by Tom Glazer, and a couple of Everybody Sing! anthologies — and somehow I also ended up with my grandparents’ 78 albums.

6, 33 1/3, 45, and 78. They wouldn’t let me play their records on it, but I had a few children’s folk LPs — one by Tom Glazer, and a couple of Everybody Sing! anthologies — and somehow I also ended up with my grandparents’ 78 albums. but along with dozens of classical albums, they had the classic Communist record collection of the early 1940s: Paul Robeson, the Red Army Chorus, the International Brigades from the Spanish Civil War, Josh White, the Almanac Singers, and the Union Boys. The Union Boys wasn’t actually a group — it was just a bunch of singers who got together to record an album’s worth of songs about union organizing and the war effort, among them Pete Seeger, Burl Ives, Tom Glazer, Josh White, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, plus one side by Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston.

but along with dozens of classical albums, they had the classic Communist record collection of the early 1940s: Paul Robeson, the Red Army Chorus, the International Brigades from the Spanish Civil War, Josh White, the Almanac Singers, and the Union Boys. The Union Boys wasn’t actually a group — it was just a bunch of singers who got together to record an album’s worth of songs about union organizing and the war effort, among them Pete Seeger, Burl Ives, Tom Glazer, Josh White, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, plus one side by Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston. I played those records constantly and learned most of the songs, and these two were particular favorites. I suppose part of the appeal was the war — despite my parents’ pacifist leanings, I played with toy soldiers and dug trenches and all that kind of stuff, and it was exciting to sing about rolling into Berlin with your buddies from the union and going after Hitler. I didn’t understand all the words, of course — I don’t think I knew the meaning of either UAW or CIO — but thirty years later, when I helped organize a freelancer’s group at the Boston Globe under the auspices of the National Writers Union, I was particularly pleased that we were a subsection of the UAW. It kind of brought everything full circle, and felt like I’d stayed true to my early friends.

I played those records constantly and learned most of the songs, and these two were particular favorites. I suppose part of the appeal was the war — despite my parents’ pacifist leanings, I played with toy soldiers and dug trenches and all that kind of stuff, and it was exciting to sing about rolling into Berlin with your buddies from the union and going after Hitler. I didn’t understand all the words, of course — I don’t think I knew the meaning of either UAW or CIO — but thirty years later, when I helped organize a freelancer’s group at the Boston Globe under the auspices of the National Writers Union, I was particularly pleased that we were a subsection of the UAW. It kind of brought everything full circle, and felt like I’d stayed true to my early friends. The title song was his own composition–he was always trying to come up with new approaches to old blues styles, and this is a perfect example: the humor and language are a mix of his modern sensibility and the kind of street lingo he enjoyed in songs and books from earlier eras, in keeping with the tastes of a man who named his rock band the Hudson Dusters after one of the Irish street gangs in Herbert Asbury’s Gangs of New York. For example, to be in tap city is an extension of “tapping out,” or going broke at poker.

The title song was his own composition–he was always trying to come up with new approaches to old blues styles, and this is a perfect example: the humor and language are a mix of his modern sensibility and the kind of street lingo he enjoyed in songs and books from earlier eras, in keeping with the tastes of a man who named his rock band the Hudson Dusters after one of the Irish street gangs in Herbert Asbury’s Gangs of New York. For example, to be in tap city is an extension of “tapping out,” or going broke at poker. so I settled for playing a couple of Johnson’s pieces, with some licks from Son House, who seems to have been the main source for his slide style, and this is the one that stuck with me.

so I settled for playing a couple of Johnson’s pieces, with some licks from Son House, who seems to have been the main source for his slide style, and this is the one that stuck with me.

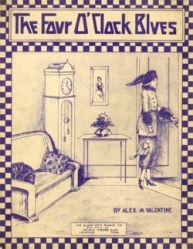

Which said, Dunn’s recording is an instrumental, and the published sheet music has lyrics that bear no resemblance to what Johnson sang… and the song was also published in Memphis around that time with credit to another composer, Alex Valentine… and Skip James recorded a version of the song as “Four O’Clock Blues,” before Johnson did it, with yet another set of lyrics… and Alan Lomax recorded yet another version of the song in 1941 from Son House, Willie Brown, and Fiddlin’ Joe Martin, who could have been Johnson’s source…

Which said, Dunn’s recording is an instrumental, and the published sheet music has lyrics that bear no resemblance to what Johnson sang… and the song was also published in Memphis around that time with credit to another composer, Alex Valentine… and Skip James recorded a version of the song as “Four O’Clock Blues,” before Johnson did it, with yet another set of lyrics… and Alan Lomax recorded yet another version of the song in 1941 from Son House, Willie Brown, and Fiddlin’ Joe Martin, who could have been Johnson’s source…