One of the records I bought during that year in New York forever changed my understanding of the world. Like much of what I was buying, it was a reissue of recordings from the 1920s and 1930s on the Yazoo label, but this one had a particularly strange cover and a title cribbed from a James Baldwin novel: Mr. Charlie’s Blues. Its concept was to collect recordings by white rural musicians who played similar material in a similar style to the many black musicians on Yazoo’s other LPs, presenting them as blues musicians rather than as hillbilly, country, or old-time musicians.

in a similar style to the many black musicians on Yazoo’s other LPs, presenting them as blues musicians rather than as hillbilly, country, or old-time musicians.

What was life-changing about that was not the idea of white musicians playing blues — obviously, I was in New York to study with Dave Van Ronk, so I was familiar with that concept. Nor was it that the musicians on the Yazoo LP were particularly adept or skilled white blues musicians — their skills and my appreciation for their work varied, as with the white blues revivalists in Cambridge and New York.

What was different about them was that, at least to my ears, they were not trying to sound black. Some of them were playing guitar parts clearly imitated from records by black players, and a lot of them would have called their style “n—er picking,” a standard term for fingerstyle guitar in the rural South that was later cleaned up to “Travis picking.” (A change that removes the derogatory racial term while shifting credit for the style from its African American originators to one of its most expert white practitioners — a familiar message from white America to black America: “Heads I win, tails you lose.”) But they were singing in their own voices, sounding like white rural southerners, and in general choosing material that fit their own lives and perspectives.

Take Dick Justice, my favorite artist on that collection: he had two songs, both of which I instantly added to my repertoire, and sounded completely natural singing them. I’ve recently learned a lot more about Justice, having assembled a chapter about him for the book that accompanies the American Epic film and recording project, which includes lots of new information about him. (As well as some very nice photographs, which I’m currently not at liberty to reproduce here.)

Take Dick Justice, my favorite artist on that collection: he had two songs, both of which I instantly added to my repertoire, and sounded completely natural singing them. I’ve recently learned a lot more about Justice, having assembled a chapter about him for the book that accompanies the American Epic film and recording project, which includes lots of new information about him. (As well as some very nice photographs, which I’m currently not at liberty to reproduce here.)

Justice was a coal miner and something of a hell-raiser in his youth, in a community with a small clique of exceptional musicians, and apparently this song was very popular with them. His children don’t recall him singing it, but the son of Bill Williamson, whose father was a friend of Justice and recorded with the Williamson Brothers and Curry, recalls it as a favorite of his dad’s, saying: “He could get on the piano and play blues like crazy, you know. He used to do a song called ‘Cocaine’, but it had a verse in it about the furniture man, so he liked to the call it ‘The Furniture Man’. And he would just do it like a comedy skit, and just crack everybody up.” (For more on the comic implications of furniture men with particular relevance to this song, here is an interesting post from another blog site.)

“Cocaine” was the title of Justice’s record as well, and he’d learned the song off a record called “Cocaine Blues” by a black guitarist and singer from Virginia named Luke Jordan — which is why, when Dave Van Ronk recorded a completely different song called “Cocaine Blues” it was initially credited to Jordan… and why I and others have chosen to give it a title that differentiates it. Jordan is another wonderful artist, and his record is very similar to Justice’s, and if I’d heard it first I’d credit him as my source… but I didn’t…

“Cocaine” was the title of Justice’s record as well, and he’d learned the song off a record called “Cocaine Blues” by a black guitarist and singer from Virginia named Luke Jordan — which is why, when Dave Van Ronk recorded a completely different song called “Cocaine Blues” it was initially credited to Jordan… and why I and others have chosen to give it a title that differentiates it. Jordan is another wonderful artist, and his record is very similar to Justice’s, and if I’d heard it first I’d credit him as my source… but I didn’t…

And frankly it was a better lesson for me to hear Justice, because, as I began to write above, he didn’t try to sing with a “black” voice, and over the years I have tried to assimilate that lesson, and also to try not to sing with a “southern” voice. I don’t always succeed, by any means, because those voices have been in my head all my life — and there are some lyrics that don’t work in my accent, because the words don’t rhyme or scan — but I’m trying, because I was struck by something Martin Carthy told me when I asked why he didn’t sing a Scottish ballad in Scots dialect:

I won’t try and put on a Scottish accent or put on an Irish accent or put on a regional English accent, cause I think that’s nonsense, I think it’s silly actually. It makes the whole thing into a pantomime. It’s much more serious than that for me. And much more fun, as well. You’re actually being able to concentrate on the song, to concentrate on the job at hand, instead of wondering whether you’ve got the accent right. It’s like you’re playing a character, but that’s not how I see singing.

I had never thought of it quite that way, and I don’t think it necessarily applies to all songs and styles, but in general it made sense to me. I still like to sing some songs in character, and think they work well that way — acting is just as valid artistically as music or poetry, though in a different way — but in general I think it’s a good idea to try to sing like yourself, especially if you’re singing something like blues, where the whole point is direct communication. So as best I can I’ve been trying to figure out how to do that — for better or worse, and for what it’s worth.

Bessie Smith’s complete recordings, with their comprehensive notes by Chris Albertson. That set was an oddity of the LP era: the records were issued with the notion that they could be stacked and played in order, all ten of them, so volume one had Smith’s first and last recordings, and the subsequent albums narrowed to volume five, which was the only one to include four sides of music from a single period…

Bessie Smith’s complete recordings, with their comprehensive notes by Chris Albertson. That set was an oddity of the LP era: the records were issued with the notion that they could be stacked and played in order, all ten of them, so volume one had Smith’s first and last recordings, and the subsequent albums narrowed to volume five, which was the only one to include four sides of music from a single period… I’m guessing Henderson hired someone else to do those duties. Since another song at the same session was “Them’s Graveyard Words” and six months later Smith recorded another Brooks song called “Dyin’ By the Hour,” it seems to have been a pretty doom-laden period for whatever lyricist was involved.

I’m guessing Henderson hired someone else to do those duties. Since another song at the same session was “Them’s Graveyard Words” and six months later Smith recorded another Brooks song called “Dyin’ By the Hour,” it seems to have been a pretty doom-laden period for whatever lyricist was involved. sings a somewhat different lyric, but that may just be a quirk of memory or he may have decided to do some rewriting, which he often did when he found an old song he liked. I have to say, though, now that I’m going back and listening to their versions, I’m a bit startled that he would have softened their final verse, which goes:

sings a somewhat different lyric, but that may just be a quirk of memory or he may have decided to do some rewriting, which he often did when he found an old song he liked. I have to say, though, now that I’m going back and listening to their versions, I’m a bit startled that he would have softened their final verse, which goes: just too female. But Dave loved their singing, and the piano or small combo arrangements that framed their singing, and he also had a keen appreciation of professional songwriters — he thought the folk scene’s tendency to praise products of the oral tradition over the products of people like Cole Porter and Duke Ellington was basically a middle class affectation — he liked to use the French term, nostalgie de la boue, a yearning for the mud. Dave thought of himself as a professional musician and liked the company of professional musicians, and he took particular took pride in having known Clarence Williams, who had organized the Hunter, Smith, and Johnson recording sessions.

just too female. But Dave loved their singing, and the piano or small combo arrangements that framed their singing, and he also had a keen appreciation of professional songwriters — he thought the folk scene’s tendency to praise products of the oral tradition over the products of people like Cole Porter and Duke Ellington was basically a middle class affectation — he liked to use the French term, nostalgie de la boue, a yearning for the mud. Dave thought of himself as a professional musician and liked the company of professional musicians, and he took particular took pride in having known Clarence Williams, who had organized the Hunter, Smith, and Johnson recording sessions. Delaney, and it wouldn’t surprise me if the confusion dated back to Dave’s time hanging out with Williams, who was notorious for making a buck of other people’s material — he credited Delaney on the records he produced, but the fact that he used this song with multiple artists suggests he probably owned the publishing, and maybe a cut of the composer royalties as well. In any case, it’s a nice example of the sort of song Dave loved and that I probably wouldn’t know if he hadn’t done it… though it was way more popular than the country blues songs I favored, and when I started playing on the street with my friend Rob Forbes in the summer of 1977, this was one his mother always requested because she had performed it as a band vocalist in the 1940s.

Delaney, and it wouldn’t surprise me if the confusion dated back to Dave’s time hanging out with Williams, who was notorious for making a buck of other people’s material — he credited Delaney on the records he produced, but the fact that he used this song with multiple artists suggests he probably owned the publishing, and maybe a cut of the composer royalties as well. In any case, it’s a nice example of the sort of song Dave loved and that I probably wouldn’t know if he hadn’t done it… though it was way more popular than the country blues songs I favored, and when I started playing on the street with my friend Rob Forbes in the summer of 1977, this was one his mother always requested because she had performed it as a band vocalist in the 1940s. This was one of Morton’s most subtle efforts, and one of Dave’s. Dave stripped the spare piano accompaniment down to an even sparer guitar arrangement, and sang it simply and directly, just telling the story.

This was one of Morton’s most subtle efforts, and one of Dave’s. Dave stripped the spare piano accompaniment down to an even sparer guitar arrangement, and sang it simply and directly, just telling the story. I wrote a good deal more about this song, and what little more is known about Desdunes, in my book Jelly Roll Blues. Morton remembered that she was missing a couple of fingers on her right hand, and I found a newspaper clipping that told how her hand was crushed in a trolley accident. I also turned up a bunch of songs with overlapping verses, especially about the hard life of streetwalkers, but never managed to sort out the train schedules…

I wrote a good deal more about this song, and what little more is known about Desdunes, in my book Jelly Roll Blues. Morton remembered that she was missing a couple of fingers on her right hand, and I found a newspaper clipping that told how her hand was crushed in a trolley accident. I also turned up a bunch of songs with overlapping verses, especially about the hard life of streetwalkers, but never managed to sort out the train schedules… Morton was improvising an explanation to match the lyric, and very likely shifting the location: there was a 219 train that ran from Memphis to Little Rock, with the 220 returning, and this couplet may well be from Memphis, another strong blues town. On the other hand, another famous blues lyric that mentions the 219 is “Trouble In Mind” (“Gonna lay my head on that lonesome railroad line/ Let the 219 ease my trouble in mind”), by Richard M. Jones, who was also from New Orleans.

Morton was improvising an explanation to match the lyric, and very likely shifting the location: there was a 219 train that ran from Memphis to Little Rock, with the 220 returning, and this couplet may well be from Memphis, another strong blues town. On the other hand, another famous blues lyric that mentions the 219 is “Trouble In Mind” (“Gonna lay my head on that lonesome railroad line/ Let the 219 ease my trouble in mind”), by Richard M. Jones, who was also from New Orleans. Red Hot Peppers recordings — by some standards the first examples of jazz that was both carefully arranged and brilliantly swinging — but in terms of Dave’s repertoire the most significant Morton record was an album recorded in 1939 as a commercial follow-up to his Library of Congress sessions, featuring Morton alone at the piano and titled New Orleans Memories. It was reissued on LP in the 1950s with one side of instrumentals and one of Morton singing. There were five songs on the latter side, all of which Dave played, and eventually I learned them as well, in roughly equal parts from Dave and Morton.

Red Hot Peppers recordings — by some standards the first examples of jazz that was both carefully arranged and brilliantly swinging — but in terms of Dave’s repertoire the most significant Morton record was an album recorded in 1939 as a commercial follow-up to his Library of Congress sessions, featuring Morton alone at the piano and titled New Orleans Memories. It was reissued on LP in the 1950s with one side of instrumentals and one of Morton singing. There were five songs on the latter side, all of which Dave played, and eventually I learned them as well, in roughly equal parts from Dave and Morton. That theme, “funky butt, funky butt, take it away,” has often been glossed by jazz historians as a reference to farting, possibly because the historians were more comfortable with pre-adolescent naughtiness than with adult sexuality. Bolden was famous for the audience of prostitutes who patronized his dances, and everyone in that world seems to have associated the “funk” in his lyrics with the strong smell of female bodies after a long night’s work. In my book,

That theme, “funky butt, funky butt, take it away,” has often been glossed by jazz historians as a reference to farting, possibly because the historians were more comfortable with pre-adolescent naughtiness than with adult sexuality. Bolden was famous for the audience of prostitutes who patronized his dances, and everyone in that world seems to have associated the “funk” in his lyrics with the strong smell of female bodies after a long night’s work. In my book,  and he expanded it in the early 1960s into a guitar transcription of the classic ragtime composition, “

and he expanded it in the early 1960s into a guitar transcription of the classic ragtime composition, “ so I emerged from my year of study with “

so I emerged from my year of study with “ Dave’s favorite composer and one of his favorite musicians, alongside Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong.

Dave’s favorite composer and one of his favorite musicians, alongside Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. Ton Van Bergeyk, and also Leo Wijnkamp, and then I introduced him to Guy Van Duser’s work, which led him to begin musing about the unique affinity Dutch and Dutch-American guitarists seemed to have for ragtime… until his lady, Joanne, broke in to point out that he had about as much Dutch ancestry as he had Cherokee.

Ton Van Bergeyk, and also Leo Wijnkamp, and then I introduced him to Guy Van Duser’s work, which led him to begin musing about the unique affinity Dutch and Dutch-American guitarists seemed to have for ragtime… until his lady, Joanne, broke in to point out that he had about as much Dutch ancestry as he had Cherokee. money behind him, and hopes that he might get a hit that would break him beyond the bar and coffeehouse circuit and make life a little easier (for more on this, check out my post on “

money behind him, and hopes that he might get a hit that would break him beyond the bar and coffeehouse circuit and make life a little easier (for more on this, check out my post on “ although this rococo Roy-Rogers-on-mescaline cowboy song was the only item of Stampfeliana that remained in his repertoire in later years, that was because the others required more accompaniment than his guitar — for example, the avant-garde art-rock cacophony of “

although this rococo Roy-Rogers-on-mescaline cowboy song was the only item of Stampfeliana that remained in his repertoire in later years, that was because the others required more accompaniment than his guitar — for example, the avant-garde art-rock cacophony of “

hoping for at least a modest hit, but the last of those had been in 1973 and now he was with Philo, a small Vermont folk label, and although he was proud of the music he was making, it was clear he wasn’t going to get out of his one-bedroom apartment with its windows on an airshaft, and not entirely clear how he’d manage the rent on that.

hoping for at least a modest hit, but the last of those had been in 1973 and now he was with Philo, a small Vermont folk label, and although he was proud of the music he was making, it was clear he wasn’t going to get out of his one-bedroom apartment with its windows on an airshaft, and not entirely clear how he’d manage the rent on that. sold a gazillion records with it.

sold a gazillion records with it. had the requisite world-weariness, and was a good actor and terrific storyteller, and I can imagine his gruff whisper being perfect for this role.

had the requisite world-weariness, and was a good actor and terrific storyteller, and I can imagine his gruff whisper being perfect for this role. just a weird kid with too much nervous energy and a scratchy voice. Dave and his wife Terri Thal were major boosters for the kid, mentoring him, finding him jobs, and teaching him songs.

just a weird kid with too much nervous energy and a scratchy voice. Dave and his wife Terri Thal were major boosters for the kid, mentoring him, finding him jobs, and teaching him songs. The melody was from a song called “The Young Man Who Wouldn’t Hoe Corn,” which I’m assuming Dylan, like everyone else, got from Pete Seeger, who recorded it in the mid-1950s on an album of frontier ballads.

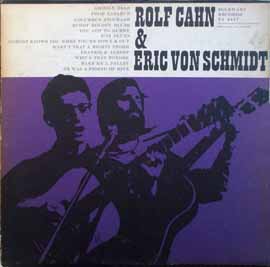

The melody was from a song called “The Young Man Who Wouldn’t Hoe Corn,” which I’m assuming Dylan, like everyone else, got from Pete Seeger, who recorded it in the mid-1950s on an album of frontier ballads. a duet LP with Rolf Cahn for the Folkways label that has not been treated well by history but was a seminal source for the folk-blues revivalists of the early 1960s. His source was a singer and guitarist named Smith Casey or Smith Cason, or possibly Smith Carson, who was recorded by John Lomax for the Library in 1939 at the Clemens State Prison Farm in Brazoria, Texas. In the LOC files it was titled “

a duet LP with Rolf Cahn for the Folkways label that has not been treated well by history but was a seminal source for the folk-blues revivalists of the early 1960s. His source was a singer and guitarist named Smith Casey or Smith Cason, or possibly Smith Carson, who was recorded by John Lomax for the Library in 1939 at the Clemens State Prison Farm in Brazoria, Texas. In the LOC files it was titled “ arrangement that turned a fairly generic blues lament into something great and enduring. Play his version back to back with Dylan’s, and the only difference is that Dylan’s is one of the many good but ultimately forgettable folk-blues songs he was singing in 1961-62, while Dave’s is a masterpiece.

arrangement that turned a fairly generic blues lament into something great and enduring. Play his version back to back with Dylan’s, and the only difference is that Dylan’s is one of the many good but ultimately forgettable folk-blues songs he was singing in 1961-62, while Dave’s is a masterpiece.