Elijah Wald – Dylan Goes Electric!

Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night that Split the Sixties

[Home] [Bio] [Jelly Roll Blues] [Robert Johnson] [Dave Van Ronk] [Narcocorrido] [Dylan Goes Electric] [Beatles/Pop book] [The Dozens] [The Blues] [Josh White] [Hitchhiking] [The Blues] [Other writing] [CD and album projects] [Joseph Spence]

Dylan Goes Electric! Dylan, Seeger, Newport, and the Night that Split the Sixties (Dey Street/HarperCollins 2015). Please buy from your local bookstore or through Bookshop.org, which credits local bookstores.

"a fantastic retelling of events from the early '60s that led up to the fiasco at Newport." --Bob Dylan

Now the basis for a major motion picture, A Complete Unknown, directed by James Mangold and starring Timothée Chalamet.

Published by Dey Street/HarperCollins, July 2015.

Published by Dey Street/HarperCollins, July 2015.

(click for reviews)

(errata--my errors; please let me know if you find others)

On the evening of July 25, 1965, Bob Dylan took the stage at Newport Folk Festival backed by an electric band and roared into a blistering version of "Maggie's Farm," followed by his new rock hit, "Like a Rolling Stone." The audience of committed folkies and political activists who had hailed him as their acoustic prophet (mixed with some young rock fans who loved the Byrds and Beatles and his new sound) reacted with a mix of shock, booing, and cheers. It was the shot heard round the world—Dylan’s declaration of musical independence, the end of the folk revival, and the birth of rock as the voice of a generation—and one of the defining moments in twentieth-century music.

Dylan Goes Electric! puts that night in the cultural, political and historical context of its time, traces Dylan's evolution as a searching and omnivorous musician, explores what Newport was and meant, and restores Pete Seeger to the central role he played in the festival and the whole concept of folk music as it was understood in that time. Based on new interviews, previously untapped sources, and untold hours of unreleased Newport tapes, it provides unexpected additions and insights to a story that has been mythologized but never seriously explored. Along the way, it delves deep into the folk revival, the rise of rock, and the tensions between traditional and groundbreaking music to provide new insights into Dylan’s artistic evolution, his special affinity to blues, his complex relationship to the folk establishment and his sometime mentor Pete Seeger, and the ways he reshaped popular music forever. That brief set at Newport became a stand-in for much wider rifts--it marked a divide between the early sixties of the civil rights movement, civil defense drills, the old left, and folk music and the sixties most of us remember: Vietnam, Black power, hippies, the New Left, and rock. Dylan's set included only five songs, but it captured that moment in a way no other performance could, and remains a familiar touchstone fifty years later.

To order a book or ebook from your local independent bookstore: ![]()

"a deeply researched and entertaining chronicle of the culture clash that Dylan sparked from the Newport stage"

--David Remnick, The New Yorker

"splendid, colorful work of musicology and cultural history... Mr. Wald is a superb analyst of the events he describes."

--Janet Maslin, The New York Times

"a great work of scholarship, brimming with insight – among the best music books I have ever read."

--John Harris, The Guardian newspaper

"excellent... a rich study of the clash between cultural authenticity and commercial success."

--Timothy Farrington, Wall St. Journal

"touchingly captures a period and a mood...a major contribution to modern musical history."

--Mark Levine, Booklist, starred review.

"As told by Wald, the story of Dylan at Newport is not so much about music as it is about stories themselves, how they mesmerize even as they bumble along and don't always end cleanly. The truth is often messy. And usually that messiness makes for a better story."

--David Kirby, Washington Post

"Elijah Wald's book... feels like a personal statement of an important part of my life. I can't recommend it enough to anyone who is interested in those extraordinary years."

--George Wein, founder of the Newport Folk Festival

"Dylan’s wild turn at Newport was mutinous, monumental. Elijah Wald’s devastatingly smart analysis of that night – and everything that preceded it, and everything that came after – is just as thrilling. Wald is a remarkably sharp and graceful writer, capable of drawing extraordinary connections between artists, genres, and cultural moments. There’s simply no one better when it comes to unpacking not just the mechanics of American music, but the mythology of American music – the stories we tell ourselves, the stories we believe."

--Amanda Petrusich, author of Do Not Sell At Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World's Rarest 78rpm Records.

"Uh-oh: here comes Elijah Wald, skewering the accepted version with those ornery facts again, just like he did with Robert Johnson in Escaping the Delta and lots of other folks in How The Beatles Destroyed Rock 'n' Roll. In concise and entertaining fashion, this meticulously-researched book shows why the story it tells is important, and leaves you with as clear an idea as anyone but Bob Dylan has of what actually happened that night. It's a great story, masterfully told, of how the times were, indeed, a-changin' -- and why."

--Ed Ward, rock and roll historian for NPR's Fresh Air with Terry Gross, and author of Michael Bloomfield: The Rise and Fall of an American Guitar Hero.

"Elijah Wald is the kind of writer who turns your head around. His deeply informed alternate takes on popular music fans' most beloved assumptions not only fill in gaps, they reorient the whole cultural landscape. In past books, he's done it for the blues and the Beatles; now he takes on the sacredest cow of all, Bob Dylan at Newport in 1965. What Wald reveals about that most mystified of singer-songwriters and the folk and rock worlds that then surrounded and elevated him changed my own view of a moment I thought I had all figured out -- and of the songwriterly 1960s as a whole."

--Ann Powers, chief pop critic of the Los Angeles Times and author of Weird Like Us: My Bohemian America.

"In this tour de force, Elijah Wild complicates the stick-figure myth of generational succession at Newport by doing justice to what he rightly calls Bob Dylan’s “declaration of independence” without beating the life out of Pete Seeger and Joan Baez, who were defending their own. This is one of the very best accounts I’ve read of musicians fighting for their honor."

--Todd Gitlin, author of The Sixties and Occupy Nation

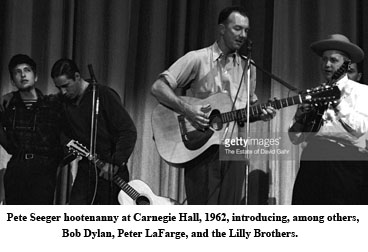

1. The House that Pete Built

The folk revival of the 1950s and 1960s was a varied, multifaceted movement, but all its facets reflected the work of one ubiquitous singer, songwriter, banjo and guitar player, sing-along leader, researcher, entertainer, and philosopher: Pete Seeger. He is often remembered as a fatherly voice of social consciousness, but he was far more. In 1950 he led the  Weavers to the top of the pop charts, and through the 1950s recorded dozens of solo LPs of traditional and recent music from around the world. As a pioneer of what Dave Van Ronk dubbed the neo-ethnic movement, he was the first northern urbanite to master southern rural instrumental techniques and fought to bring traditional artists to the center of the folk revival. Defying the McCarthy Era red-hunters, he was convicted of contempt of Congress and became a model of righteous anti-authoritarianism. He self-published the first instruction book on folk and bluegrass banjo and reams of other articles and books, as well as making numerous field recordings and films. In the early 1960s, he was a passionate advocate for a new generation of singer-songwriters. And in 1963, with his wife, Toshi, he came up with a new working model for the Newport Folk Festivals.

Weavers to the top of the pop charts, and through the 1950s recorded dozens of solo LPs of traditional and recent music from around the world. As a pioneer of what Dave Van Ronk dubbed the neo-ethnic movement, he was the first northern urbanite to master southern rural instrumental techniques and fought to bring traditional artists to the center of the folk revival. Defying the McCarthy Era red-hunters, he was convicted of contempt of Congress and became a model of righteous anti-authoritarianism. He self-published the first instruction book on folk and bluegrass banjo and reams of other articles and books, as well as making numerous field recordings and films. In the early 1960s, he was a passionate advocate for a new generation of singer-songwriters. And in 1963, with his wife, Toshi, he came up with a new working model for the Newport Folk Festivals.

2. North Country Blues

Bob Dylan grew up in Hibbing, Minnesota, listening to the hot new R&B sounds crackling through the night on a radio feed from Shreveport, Louisiana, and fronting rock 'n' roll bands called the Golden Chords and the Rock Boppers. He dreamed of being a movie star like James Dean, a singing star like Buddy Holly, or running away to join Little Richard. After a very brief stint playing piano for Bobby Vee, he headed off to college in Minneapolis, where he became part of the burgeoining folk music revival, first favoring the African American singers Odetta and Leon Bibb, then jamming with other young local players and performing at parties and coffeehouses. He was absorbing his first taste of 1950s Bohemia, reading beat novels, popping pills, hanging out in black clubs--and, thanks to Jon Pankake, Paul Nelson, and their new folk 'zine, the Little Sandy Review, he discovered Ramblin' Jack Elliott and Woody Guthrie.

Bob Dylan grew up in Hibbing, Minnesota, listening to the hot new R&B sounds crackling through the night on a radio feed from Shreveport, Louisiana, and fronting rock 'n' roll bands called the Golden Chords and the Rock Boppers. He dreamed of being a movie star like James Dean, a singing star like Buddy Holly, or running away to join Little Richard. After a very brief stint playing piano for Bobby Vee, he headed off to college in Minneapolis, where he became part of the burgeoining folk music revival, first favoring the African American singers Odetta and Leon Bibb, then jamming with other young local players and performing at parties and coffeehouses. He was absorbing his first taste of 1950s Bohemia, reading beat novels, popping pills, hanging out in black clubs--and, thanks to Jon Pankake, Paul Nelson, and their new folk 'zine, the Little Sandy Review, he discovered Ramblin' Jack Elliott and Woody Guthrie.

3. New York Town

Dylan arrived in Greenwich Village in January 1961, and over the next year he immersed himself in the local scene and developed a new musical style as he rubbed shoulders with Dave Van Ronk, Paul Clayton, Jim Kweskin, Peter Stampfel, John Lee Hooker--and, on a side trip to Cambridge, Eric Von Schmidt. He became known as an adept harmonica player, recording as a sideman with Harry Belafonte, Carolyn Hester, and the Delta bluesman Big Joe Williams, and startled his peers by getting a contract with Columbia Records. The notes to his first album described him as “one of the most compelling white blues singers ever recorded” and cited Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, and Jelly Roll Morton as influences. By the end of 1962 he had discovered Robert Johnson, recorded an electric rockabilly session, and honed a unique style mixing blues, rock 'n' roll, hillbilly, and a few of his own compositions.

Dylan arrived in Greenwich Village in January 1961, and over the next year he immersed himself in the local scene and developed a new musical style as he rubbed shoulders with Dave Van Ronk, Paul Clayton, Jim Kweskin, Peter Stampfel, John Lee Hooker--and, on a side trip to Cambridge, Eric Von Schmidt. He became known as an adept harmonica player, recording as a sideman with Harry Belafonte, Carolyn Hester, and the Delta bluesman Big Joe Williams, and startled his peers by getting a contract with Columbia Records. The notes to his first album described him as “one of the most compelling white blues singers ever recorded” and cited Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, and Jelly Roll Morton as influences. By the end of 1962 he had discovered Robert Johnson, recorded an electric rockabilly session, and honed a unique style mixing blues, rock 'n' roll, hillbilly, and a few of his own compositions.

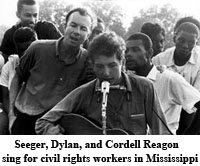

4. Blowin' In the Wind

The early 1960s was a time of optimism and paranoia, hope for a future of racial equality and fear of no future at all. In the southern freedom movement, folk music found a new purpose--Seeger connected a young singer-guitarist named Guy Carawan to the Highlander School in Tennessee and they spread a song Seeger had learned from a previous Highlander songleader, called "We Shall Overcome." In New York, Seeger suggested that Sis Cunningham start a biweekly topical songsheet called Broadside to encourage new songwriters, and Dylan became one of its most prolific contributors. His first compositions were mostly in Guthrie's style, but in the summer of 1962 he wrote "Blowin' in the Wind," and that fall Seeger introduced him at Carnegie Hall for a set that opened with a blues harmonica hoedown and a song based on a guitar riff from the Everly Brothers, but also included "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall."

5. Newport

Building on the success of an annual summer jazz festival, the Newport Folk Festival began in 1959. The festivals people remember, though, began in 1963, when Pete Seeger and his wife Toshi, along with George Wein and Theodore Bikel, came up with a new model: a festival where popular stars would be paid the same as unknown rural performers, and the crowds that came to see the familiar names would be introduced to a world of unfamiliar traditional music. For hardcore folk fans, the big news of the '63 festival was the reappearance of Mississippi John Hurt, a legendary singer who had first recorded in 1928, but for young listeners who heard folk music as the sound of their times, the iconic moment came at the end of the first night's concert, when Dylan--a 22-year-old songwriter still barely known outside New York--was joined onstage by Seeger, Joan Baez, Peter, Paul and Mary, the Freedom Singers, and Bikel, linking arms and singing "Blowin' in the Wind" and "We Shall Overcome."

Building on the success of an annual summer jazz festival, the Newport Folk Festival began in 1959. The festivals people remember, though, began in 1963, when Pete Seeger and his wife Toshi, along with George Wein and Theodore Bikel, came up with a new model: a festival where popular stars would be paid the same as unknown rural performers, and the crowds that came to see the familiar names would be introduced to a world of unfamiliar traditional music. For hardcore folk fans, the big news of the '63 festival was the reappearance of Mississippi John Hurt, a legendary singer who had first recorded in 1928, but for young listeners who heard folk music as the sound of their times, the iconic moment came at the end of the first night's concert, when Dylan--a 22-year-old songwriter still barely known outside New York--was joined onstage by Seeger, Joan Baez, Peter, Paul and Mary, the Freedom Singers, and Bikel, linking arms and singing "Blowin' in the Wind" and "We Shall Overcome."

6. Times A-Changin'

For many listeners in the early 1960s Dylan embodied the ideals of the folk revival: a young hobo, drifting out of the West, singing old songs he had learned in his travels and writing new songs about the trials, troubles, and tribulations of the world around him. He wrote songs about everything that came into his mind--love songs, outlaw ballads, rhymed comic monologues, ragtime novelties, blues--but for a lot of people, what mattered most were his songs of social consciousness. He was hailed as the voice of a generation, and the pressure to live up to that description increasingly felt like a burden. Meanwhile, folk music was changing from a secret music shared by devoted fans into a mass-market commodity with number one hits, pop singers jumping on the bandwagon, and a national TV show called Hootenanny--which was named after Pete Seeger's singalong gatherings, but banned Pete himself as overly controversial.

For many listeners in the early 1960s Dylan embodied the ideals of the folk revival: a young hobo, drifting out of the West, singing old songs he had learned in his travels and writing new songs about the trials, troubles, and tribulations of the world around him. He wrote songs about everything that came into his mind--love songs, outlaw ballads, rhymed comic monologues, ragtime novelties, blues--but for a lot of people, what mattered most were his songs of social consciousness. He was hailed as the voice of a generation, and the pressure to live up to that description increasingly felt like a burden. Meanwhile, folk music was changing from a secret music shared by devoted fans into a mass-market commodity with number one hits, pop singers jumping on the bandwagon, and a national TV show called Hootenanny--which was named after Pete Seeger's singalong gatherings, but banned Pete himself as overly controversial.

7. Jingle-Jangle Morning

In February 1964, the Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show. Over the next year and a half, the folk scene tried to come to terms with a new competitor: rock 'n' roll that was not just fun teenage dance music, but appealed to intelligent, socially committed college students as well. It wasn't just rock: there were also the Persuasions and Sam Cooke, Chuck Berry writing better than ever, Johnny Rivers getting hits with Pete Seeger and Leadbelly songs--and Dylan, who was now writing about a pied piper called the "Tambourine Man" who would take him "disappearing through the smoke rings of my mind." In Britain, young rockers covered his songs and imitated his style, and the Beatles and Rolling Stones named him as an influence; in the US, Johnny Cash hailed him from the stage of the Newport Folk Festival as "the best songwriter of the age, since Pete Seeger." His songs were getting longer, more complicated, and harder for his old fans to understand. By the spring of 1965 his new album included some tracks with an electric rock band and he had a hot single on the radio. Meanwhile, the folk world was changing as well: the month before that summer's Newport festival, the New York Folk Festival included a blues evening featuring Muddy Waters' electric Chicago band and Chuck Berry.

In February 1964, the Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show. Over the next year and a half, the folk scene tried to come to terms with a new competitor: rock 'n' roll that was not just fun teenage dance music, but appealed to intelligent, socially committed college students as well. It wasn't just rock: there were also the Persuasions and Sam Cooke, Chuck Berry writing better than ever, Johnny Rivers getting hits with Pete Seeger and Leadbelly songs--and Dylan, who was now writing about a pied piper called the "Tambourine Man" who would take him "disappearing through the smoke rings of my mind." In Britain, young rockers covered his songs and imitated his style, and the Beatles and Rolling Stones named him as an influence; in the US, Johnny Cash hailed him from the stage of the Newport Folk Festival as "the best songwriter of the age, since Pete Seeger." His songs were getting longer, more complicated, and harder for his old fans to understand. By the spring of 1965 his new album included some tracks with an electric rock band and he had a hot single on the radio. Meanwhile, the folk world was changing as well: the month before that summer's Newport festival, the New York Folk Festival included a blues evening featuring Muddy Waters' electric Chicago band and Chuck Berry.

8. Electricity in the Air

.jpg) The 1965 Newport Folk Festival was full of new sounds, new styles, and new conflicts. The line-up included a British Invasion pop star named Donovan, an electric R&B quartet called the Chambers Brothers,

The 1965 Newport Folk Festival was full of new sounds, new styles, and new conflicts. The line-up included a British Invasion pop star named Donovan, an electric R&B quartet called the Chambers Brothers, and, straight out of Chicago, the Butterfield Blues Band. Reactions were mixed: Alan Lomax, the grand old man of traditional folklore, applauded the Chambers Brothers as a breath of fresh air but gave the Butterfield band an introduction so lukewarm that soon he and Albert Grossman--Dylan's manager, and shortly Butterfield's as well--were throwing punches and rolling in the dirt.

and, straight out of Chicago, the Butterfield Blues Band. Reactions were mixed: Alan Lomax, the grand old man of traditional folklore, applauded the Chambers Brothers as a breath of fresh air but gave the Butterfield band an introduction so lukewarm that soon he and Albert Grossman--Dylan's manager, and shortly Butterfield's as well--were throwing punches and rolling in the dirt.

9. Younger Than That Now

Dylan and the wave of new songwriters that had first attracted attention with lyrics about social issues were changing their styles and themes, exploring their personal lives, their imaginations, and the possibility of getting pop hits. Richard and Mimi Fariña had recorded with an electric band, and although they played at Newport with acoustic backing, they flirted with rock 'n' roll rhythms and got the crowd up and dancing in the rain. The festival organizers were still trying to focus attention on rural traditions, but many of the young fans wanted something different, a music that spoke directly to their tastes and interests--though other young fans were horrified at the thought that their annual gathering of the folk faithful was turning into a pop music market, full of reporters and callow teenyboppers pursuing radio hitmakers for autographs.

Dylan and the wave of new songwriters that had first attracted attention with lyrics about social issues were changing their styles and themes, exploring their personal lives, their imaginations, and the possibility of getting pop hits. Richard and Mimi Fariña had recorded with an electric band, and although they played at Newport with acoustic backing, they flirted with rock 'n' roll rhythms and got the crowd up and dancing in the rain. The festival organizers were still trying to focus attention on rural traditions, but many of the young fans wanted something different, a music that spoke directly to their tastes and interests--though other young fans were horrified at the thought that their annual gathering of the folk faithful was turning into a pop music market, full of reporters and callow teenyboppers pursuing radio hitmakers for autographs.

10. Like a Rolling Stone

Dylan took the stage midway through the Sunday night concert program, wearing a black leather jacket, carrying a Fender Stratocaster, and backed by members of the Butterfield Blues Band. He sang three songs, the loudest music ever played at Newport, and the crowd split between thrilled fans, horrified fans, and baffled fans who did not know what to make of it all. There were some 17,000 people at that concert, and what they heard or saw depended a lot on where they were. Some people close to the stage remember yelling because the amplified instruments were overwhelming Dylan's voice; some people further back say everyone around them loved the show; others remember being surrounded by booing. Some remember Dylan sounding great; some remember him sounding terrible. Pete Seeger was horrified by the earsplitting volume and aggression, and one of the evening's enduring myths is that he ran for an axe and tried to cut the sound cables.

Dylan took the stage midway through the Sunday night concert program, wearing a black leather jacket, carrying a Fender Stratocaster, and backed by members of the Butterfield Blues Band. He sang three songs, the loudest music ever played at Newport, and the crowd split between thrilled fans, horrified fans, and baffled fans who did not know what to make of it all. There were some 17,000 people at that concert, and what they heard or saw depended a lot on where they were. Some people close to the stage remember yelling because the amplified instruments were overwhelming Dylan's voice; some people further back say everyone around them loved the show; others remember being surrounded by booing. Some remember Dylan sounding great; some remember him sounding terrible. Pete Seeger was horrified by the earsplitting volume and aggression, and one of the evening's enduring myths is that he ran for an axe and tried to cut the sound cables.

11. Aftermath

Dylan's Newport set was immediately hailed as earthshaking and gamechanging.The folk scene tried to make sense of what had happened, some writers expressing their excitement and others interpreting it as the end of a wonderful, progressive period that had held out hopes of unifying a generation and changing humanity.Seeger searched his soul, seeking to find a lesson in his anger and disappointment. Folk-rock became the music business buzz phrase of the moment, as the Byrds, Cher, the Turtles, the Rolling Stones, and the Beatles followed their various variations on Dylan's style. Dylan, meanwhile, went his own way, touring the world with an electric band, facing angry crowds that booed and shouted "Judas!"--to which he responded with a bizarre single, backed with trombone and featuring the double-entendre chorus line, "Everybody must get stoned." Had he sold out to the pop market, or was he still a rebel iconoclast?

Dylan's Newport set was immediately hailed as earthshaking and gamechanging.The folk scene tried to make sense of what had happened, some writers expressing their excitement and others interpreting it as the end of a wonderful, progressive period that had held out hopes of unifying a generation and changing humanity.Seeger searched his soul, seeking to find a lesson in his anger and disappointment. Folk-rock became the music business buzz phrase of the moment, as the Byrds, Cher, the Turtles, the Rolling Stones, and the Beatles followed their various variations on Dylan's style. Dylan, meanwhile, went his own way, touring the world with an electric band, facing angry crowds that booed and shouted "Judas!"--to which he responded with a bizarre single, backed with trombone and featuring the double-entendre chorus line, "Everybody must get stoned." Had he sold out to the pop market, or was he still a rebel iconoclast?

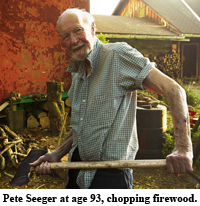

Fifty years later, Pete Seeger is gone but lived long enough to perform at the inauguration of the first black president with Bruce Springsteen singing harmony. Dylan has gone through so many changes that they could (and have) filled dozens of books--most recently an album of songs popularized by Frank Sinatra. The Newport Folk Festival, after returning in the 1980s as a somewhat lackluster nostalgia fest for aging folkies, is now attracting a new, young audience with a wave of new, young musicians who name both Seeger and Dylan as ancestors. That night at Newport in 1965 remains a touchstone, growing in importance as Dylan's influence spread beyond the bounds of folk, rock or pop and he was recognized as a pillar of modern art and artistry. The confrontation at Newport has been enshrined as the defining moment of his arrival as a complex, uncompromising artist. The instrumentation may have connected him to Elvis and the Beatles, but the booing audience connected him to Stravinsky.

Fifty years later, Pete Seeger is gone but lived long enough to perform at the inauguration of the first black president with Bruce Springsteen singing harmony. Dylan has gone through so many changes that they could (and have) filled dozens of books--most recently an album of songs popularized by Frank Sinatra. The Newport Folk Festival, after returning in the 1980s as a somewhat lackluster nostalgia fest for aging folkies, is now attracting a new, young audience with a wave of new, young musicians who name both Seeger and Dylan as ancestors. That night at Newport in 1965 remains a touchstone, growing in importance as Dylan's influence spread beyond the bounds of folk, rock or pop and he was recognized as a pillar of modern art and artistry. The confrontation at Newport has been enshrined as the defining moment of his arrival as a complex, uncompromising artist. The instrumentation may have connected him to Elvis and the Beatles, but the booing audience connected him to Stravinsky.

Reviews:

The New York Times, by Janet Maslin

The Guardian, by John Harris

Slate, by Carl Wilson

The Wall Street Journal, by Timothy Farrington

The Boston Globe, by Joseph Peschel

The Independent, by Andy Gill

The Irish Times, by Tony Clayton-Lea

The Telegraph, by Helen Brown

No Depression, by Ted Lehmann

Counterpunch, by Peter Stone Brown

PopMatters, by Jeff Strowe

Booklist

Kirkus Review

Interviews:

All Things Considered (audio and transcript)

Press site for Dylan Goes Electric!