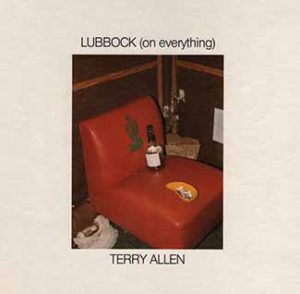

Terry Allen’s masterpiece of corrosive American dreaming, from his Lubbock (On Everything) LP. I’ve written in a previous post about my discovery of Allen’s work, but at  first I thought of him as a quirky novelty writer and it took a couple of years before I immersed myself in that album. Thirty years later, it’s still a relatively little-known (though widely acknowledged) classic, and anyone who hasn’t heard it should just go out and buy a copy.

first I thought of him as a quirky novelty writer and it took a couple of years before I immersed myself in that album. Thirty years later, it’s still a relatively little-known (though widely acknowledged) classic, and anyone who hasn’t heard it should just go out and buy a copy.

This song is Allen at his best, sketching simple lines that evoke the power and pitfalls of the romantic myths that underpin much of my life and the music I love. It opens on a stretch of western highway familiar from a million movies, the “blue asphaltum line,” beloved of James Dean and Chuck Berry, Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady, Thelma and Louise. The soundtrack is late-night radio, blasting across the Texas-Mexico border on the 250,000 watts of XERF, 1570-AM, punctuated by the dark growl of the midnight master, the Wolfman of Del Rio.

By the time I first heard Wolfman Jack, he was a chubby self-parody cruising through a second career courtesy of American Graffiti, so it took a while for me to connect him with the werevoice haunting Allen’s song. But it was the same guy. Born Robert Smith in Brooklyn, reborn as the Wolfman in Shreveport, he began  broadcasting over XERF in 1963 and in the early years concealed his identity, refusing interviews and photographs. Station promos showed a drawing of a hip wolf, or photographs of a hirsute face of uncertain ethnicity, eyes hidden behind dark shades. He broadcast from midnight till 4am, and could be

broadcasting over XERF in 1963 and in the early years concealed his identity, refusing interviews and photographs. Station promos showed a drawing of a hip wolf, or photographs of a hirsute face of uncertain ethnicity, eyes hidden behind dark shades. He broadcast from midnight till 4am, and could be  heard all over the Central and Western United States, and sometimes as far away as Europe. He played current hits, deep blues, grinding R&B, howled along with favorite records, sometimes called a lady friend live on the air, and was worshiped by millions of teenagers as a mysterious creature of the night.

heard all over the Central and Western United States, and sometimes as far away as Europe. He played current hits, deep blues, grinding R&B, howled along with favorite records, sometimes called a lady friend live on the air, and was worshiped by millions of teenagers as a mysterious creature of the night.

It is hard for those of us who came along later and were introduced to Jack and that music as nostalgic “oldies” to imagine how they sounded and what they meant to millions of listeners who heard them as the sound of a wild new world, of infinite possibilities, of escape from dead-end towns and dead-end lives.

But it is all too easy to recognize the hangover: a world of people raised on those fantasies, yearning to be daring individualists but trapped in the decaying badlands of late industrial capitalism, fighting to hold onto poisoned dreams. That’s the theme of Allen’s song, and it’s one of my favorites.

Years after I learned this, I was working on a project called River of Song with a sound crew from the Smithsonian, and one of the guys had recently finished a project about early R&B radio. One of the guys they’d planned to interview was Wolfman Jack, and he showed up at the studio ready to talk. So, they asked him, “How did you come up with your Wolfman persona?”

“It was kind of a Lord Buckley thing,” he replied.

“Who was Lord Buckley?” asked the interviewer.

“You never heard of Lord Buckley?”

The interviewer shook his head.

“Then we got nothing to talk about,” the Wolfman said, and walked out.

Ellen Steckert and Milt Okun, and for a long time I forgot about it because after I got into Woody Guthrie, Cisco Houston, and blues I tended to dismiss the songs on those albums as pseudo-folk juvenalia. I don’t remember when or why I revised my opinion — maybe I heard someone like Ian Tyson sing it — but anyway it became one of my favorites, especially when

Ellen Steckert and Milt Okun, and for a long time I forgot about it because after I got into Woody Guthrie, Cisco Houston, and blues I tended to dismiss the songs on those albums as pseudo-folk juvenalia. I don’t remember when or why I revised my opinion — maybe I heard someone like Ian Tyson sing it — but anyway it became one of my favorites, especially when  Another poster on that Mudcat thread cleared up a long-running geographical conundrum: the list of rivers in Randolph’s lyric includes the Natchez, which isn’t a river and isn’t in Texas, and Hinton, who was a Texan (born in Oklahoma, but raised in Crockett, TX), adapted that to Nacogdoches, which is in Texas but still isn’t a river (and doesn’t scan with the melody). However, the Mudcatter points out that there is a Neches River which flows through more than 400 miles of Texas. So the hired hand presumably sang “Neches” and Carlisle, being more familiar with Mississippi towns than Texas rivers, misheard it as “Natchez” — which doesn’t explain why Hinton, who grew up 30 miles from the Neches and would have had to cross it to reach Nacogdoches, didn’t make the correction.

Another poster on that Mudcat thread cleared up a long-running geographical conundrum: the list of rivers in Randolph’s lyric includes the Natchez, which isn’t a river and isn’t in Texas, and Hinton, who was a Texan (born in Oklahoma, but raised in Crockett, TX), adapted that to Nacogdoches, which is in Texas but still isn’t a river (and doesn’t scan with the melody). However, the Mudcatter points out that there is a Neches River which flows through more than 400 miles of Texas. So the hired hand presumably sang “Neches” and Carlisle, being more familiar with Mississippi towns than Texas rivers, misheard it as “Natchez” — which doesn’t explain why Hinton, who grew up 30 miles from the Neches and would have had to cross it to reach Nacogdoches, didn’t make the correction.

Nameless Coffeehouse that week or the next, I went down and heard him, and he was great. So I introduced him to Bill Morrissey and he became one of the gang, hanging out with me and Bill at Jeff McLaughlin’s house and various other places.

Nameless Coffeehouse that week or the next, I went down and heard him, and he was great. So I introduced him to Bill Morrissey and he became one of the gang, hanging out with me and Bill at Jeff McLaughlin’s house and various other places. long-running Saturday morning favorite, Hillbilly at Harvard. Our model was the Maddox Brothers and Rose, whose old radio broadcasts had recently been reissued by Arhoolie. We’d kid around and play songs, which meant working up new material every week, and we didn’t set the world on fire, but it was good practice.

long-running Saturday morning favorite, Hillbilly at Harvard. Our model was the Maddox Brothers and Rose, whose old radio broadcasts had recently been reissued by Arhoolie. We’d kid around and play songs, which meant working up new material every week, and we didn’t set the world on fire, but it was good practice. the Streetcorner Cowboys, with Robbie, Peter, me, Mark Earley on harmonica, and Matt Leavenworth showing up pretty often to sit in on fiddle. And then Peter moved to Austin, and the rest may be history, but not this history.

the Streetcorner Cowboys, with Robbie, Peter, me, Mark Earley on harmonica, and Matt Leavenworth showing up pretty often to sit in on fiddle. And then Peter moved to Austin, and the rest may be history, but not this history. The first verse, my oldest great-grandson, he made that himself, and from that each child would say a word and add to it. To tell the truth, I don’t know what got it started… but it must have been something said or something done. That’s practically how all my songs I pick up.

The first verse, my oldest great-grandson, he made that himself, and from that each child would say a word and add to it. To tell the truth, I don’t know what got it started… but it must have been something said or something done. That’s practically how all my songs I pick up. My ride dropped me in Belize City around mid-afternoon, and I wandered the streets looking for someplace cheap to stay. In those days the town looked like a rundown Caribbean port in an old movie: lines of battered, close-packed houses with carved wooden balconies sagging in the tropical heat. I was directed to a Chinese hotel that was like the place Bogart met Tim Holt and Walter Huston in Treasure of the Sierra Madre — the “rooms” were just cubicles separated by chicken wire, each with a cot and not much else. It looked thoroughly uncomfortable, and a fan at the end of the hall was doing nothing to combat the heat, so I gave it a pass.

My ride dropped me in Belize City around mid-afternoon, and I wandered the streets looking for someplace cheap to stay. In those days the town looked like a rundown Caribbean port in an old movie: lines of battered, close-packed houses with carved wooden balconies sagging in the tropical heat. I was directed to a Chinese hotel that was like the place Bogart met Tim Holt and Walter Huston in Treasure of the Sierra Madre — the “rooms” were just cubicles separated by chicken wire, each with a cot and not much else. It looked thoroughly uncomfortable, and a fan at the end of the hall was doing nothing to combat the heat, so I gave it a pass. I’d never known the words, since I’d only heard it done by Spence, who tended to mumble more than sing. So that was a nice surprise. They sang:

I’d never known the words, since I’d only heard it done by Spence, who tended to mumble more than sing. So that was a nice surprise. They sang: As for Spence, I’ve written about him in posts for “

As for Spence, I’ve written about him in posts for “ tacos tended to draw curious onlookers who also bought tacos.

tacos tended to draw curious onlookers who also bought tacos. proceeded to play me records of the “real” Mexican singers: Amalia Mendoza, Lola Beltran, the Trio Calaveras… I don’t remember who all he played, but one of the women sang this song and he was very pleased that I knew it.

proceeded to play me records of the “real” Mexican singers: Amalia Mendoza, Lola Beltran, the Trio Calaveras… I don’t remember who all he played, but one of the women sang this song and he was very pleased that I knew it. In New Orleans, I had a connection with a spare room and stayed a few days, meeting the wonderful

In New Orleans, I had a connection with a spare room and stayed a few days, meeting the wonderful  Talk about good directions! Dewey Balfa was playing fiddle with his band, and the food was good, and everybody was dancing — eventually including me, since women kept coming up and offering to show me how. I guess I was a pretty obvious foreigner, since I had a backpack and guitar leaned against my chair, and sometime later a couple of young women asked me if I needed a place to stay and offered me a spare room, and I said yes, and we drank more beer, and then Ricky Skaggs and D.L. Menard came in — Menard was opening for Skaggs at a concert somewhere in the area and brought him down afterwards.

Talk about good directions! Dewey Balfa was playing fiddle with his band, and the food was good, and everybody was dancing — eventually including me, since women kept coming up and offering to show me how. I guess I was a pretty obvious foreigner, since I had a backpack and guitar leaned against my chair, and sometime later a couple of young women asked me if I needed a place to stay and offered me a spare room, and I said yes, and we drank more beer, and then Ricky Skaggs and D.L. Menard came in — Menard was opening for Skaggs at a concert somewhere in the area and brought him down afterwards. I don’t think I saw D.L. Menard again that week, but I met him a bunch of times over the years, up in Boston and down in Louisiana. When we did the PBS series River of Song, I insisted he be the featured Cajun musician and we filmed his band playing at a crawfish boil in his backyard. A few years later, when Sandrine and I were living in New Orleans, I brought her to see him because she’d been hearing Cajun announcers on the radio who weren’t native speakers and needed to be convinced that it was a real language, not just Americans speaking bad French. We drove out to D.L.’s place in Erath, and he met us in the yard with his chihuahua named Taco, and waxed eloquent, as always. He was playing every weekend for one of those dopey comic wedding dinner theater things, “Boudreaux and Thibodeaux’s Cajun Wedding,” and loved it — his particular phrase of approbation was, “C’est fast, Jack!”

I don’t think I saw D.L. Menard again that week, but I met him a bunch of times over the years, up in Boston and down in Louisiana. When we did the PBS series River of Song, I insisted he be the featured Cajun musician and we filmed his band playing at a crawfish boil in his backyard. A few years later, when Sandrine and I were living in New Orleans, I brought her to see him because she’d been hearing Cajun announcers on the radio who weren’t native speakers and needed to be convinced that it was a real language, not just Americans speaking bad French. We drove out to D.L.’s place in Erath, and he met us in the yard with his chihuahua named Taco, and waxed eloquent, as always. He was playing every weekend for one of those dopey comic wedding dinner theater things, “Boudreaux and Thibodeaux’s Cajun Wedding,” and loved it — his particular phrase of approbation was, “C’est fast, Jack!” I put the story in my mind and I took it from the everyday procedures; every once in a while I hear or see that people would get drunk and was too ashamed to go in the front door, that they’d come in through the back door so that nobody could see them….

I put the story in my mind and I took it from the everyday procedures; every once in a while I hear or see that people would get drunk and was too ashamed to go in the front door, that they’d come in through the back door so that nobody could see them….  the time, and I studied that man from head to toe…

the time, and I studied that man from head to toe… their hand at the ragtime style.

their hand at the ragtime style. of Mills’s 19th century ragtime hits, but at the time, it was not significantly more successful than his “Whistling Rufus,” another title capitalizing on the rage for cakewalks and “coon songs.” He would soon follow these up with other hits, most memorably his tribute to the 1904 World’s Fair, “Meet Me In St. Louis, Louis” and the pseudo-Native American love song, “Red Wing,” which is probably best known today as the melodic source for Woody Guthrie’s “Union Maid.”

of Mills’s 19th century ragtime hits, but at the time, it was not significantly more successful than his “Whistling Rufus,” another title capitalizing on the rage for cakewalks and “coon songs.” He would soon follow these up with other hits, most memorably his tribute to the 1904 World’s Fair, “Meet Me In St. Louis, Louis” and the pseudo-Native American love song, “Red Wing,” which is probably best known today as the melodic source for Woody Guthrie’s “Union Maid.” of that early period went unrecorded. It seems safe to assume that some guitarists came up with settings, and as evidence in favor of this assumption, the cover of “Whistling Rufus” showed an African American guitarist apparently playing fingerstyle — an offensively stereotyped image, but all the more suggestive of a familiar tradition of black instrumentalists who played this sort of tune.

of that early period went unrecorded. It seems safe to assume that some guitarists came up with settings, and as evidence in favor of this assumption, the cover of “Whistling Rufus” showed an African American guitarist apparently playing fingerstyle — an offensively stereotyped image, but all the more suggestive of a familiar tradition of black instrumentalists who played this sort of tune. Michael Tyzack. He was a painter, prominent in the art department at the University, and also played trumpet in a trad band. At that point he was living in a big old house where he let me sleep in a spare room, and getting around in a wheelchair because he’d broken up with a woman who did not take kindly to the situation and smashed him into a wrought iron fence with her car, breaking his legs in multiple places. Unsurprisingly he was feeling rather down, seemed to like having company, and said nice things about

Michael Tyzack. He was a painter, prominent in the art department at the University, and also played trumpet in a trad band. At that point he was living in a big old house where he let me sleep in a spare room, and getting around in a wheelchair because he’d broken up with a woman who did not take kindly to the situation and smashed him into a wrought iron fence with her car, breaking his legs in multiple places. Unsurprisingly he was feeling rather down, seemed to like having company, and said nice things about  This is generally known as “Winin’ Boy,” but that title is a mistake. Morton sounds like he could be singing those words, so I don’t blame the record folks for getting it wrong, and after they issued it Morton wrote the title that way himself in a couple of letters — but if you listen to him talk about it on his Library of Congress recordings, he clearly says “Winding Ball.”

This is generally known as “Winin’ Boy,” but that title is a mistake. Morton sounds like he could be singing those words, so I don’t blame the record folks for getting it wrong, and after they issued it Morton wrote the title that way himself in a couple of letters — but if you listen to him talk about it on his Library of Congress recordings, he clearly says “Winding Ball.” Von Schmidt, Dave Van Ronk, and Ian Buchanan, who recorded a nice guitar version on the Elektra Blues Project LP (which he calls “Winding Boy”), inspiring Jorma Kaukonen’s version with Hot Tuna, which made it even more of a standard. All of those people sang Morton’s cleaned-up version, without the filthy verses that only surfaced later, when daring little record labels began exhuming the material that had been censored in earlier releases. I sing the clean version, too, because those verses really are nasty, though historically illuminating.

Von Schmidt, Dave Van Ronk, and Ian Buchanan, who recorded a nice guitar version on the Elektra Blues Project LP (which he calls “Winding Boy”), inspiring Jorma Kaukonen’s version with Hot Tuna, which made it even more of a standard. All of those people sang Morton’s cleaned-up version, without the filthy verses that only surfaced later, when daring little record labels began exhuming the material that had been censored in earlier releases. I sing the clean version, too, because those verses really are nasty, though historically illuminating. Jack’s was a legendary blues and rock venue, with pictures of previous acts including Spider John Koerner, Bonnie Raitt, and George Thorogood on the walls. Somehow they booked me, and I figured I needed some help and pulled in a bunch of friends — John Lincoln Wright came over from the Plough & Stars to sing “San Antonio Rose,” Kenny Holladay jammed on a version of “Mustang Sally” along with a trombone player from the audience, Tom Ghent sang a couple, and I think Peter Keane was there, and Robbie Phillips on washtub bass. I passed Tracy Chapman playing on the street in Harvard Square that afternoon and invited her, but alas she didn’t show.

Jack’s was a legendary blues and rock venue, with pictures of previous acts including Spider John Koerner, Bonnie Raitt, and George Thorogood on the walls. Somehow they booked me, and I figured I needed some help and pulled in a bunch of friends — John Lincoln Wright came over from the Plough & Stars to sing “San Antonio Rose,” Kenny Holladay jammed on a version of “Mustang Sally” along with a trombone player from the audience, Tom Ghent sang a couple, and I think Peter Keane was there, and Robbie Phillips on washtub bass. I passed Tracy Chapman playing on the street in Harvard Square that afternoon and invited her, but alas she didn’t show. As for this song, it isn’t by Woody Guthrie; as any damn fool oughta know, it’s by Merle Haggard. It wasn’t one of his biggest hits — which is to say, he had four number one country hits in a row before it and four after it, but this only made it to number 3 — but it fitted the romantic notion of hobo life I was chasing, and I love the line about “this mental fat I’m chewing.”

As for this song, it isn’t by Woody Guthrie; as any damn fool oughta know, it’s by Merle Haggard. It wasn’t one of his biggest hits — which is to say, he had four number one country hits in a row before it and four after it, but this only made it to number 3 — but it fitted the romantic notion of hobo life I was chasing, and I love the line about “this mental fat I’m chewing.” road. I ended up sleeping outside a lot of nights and even taking gainful employment, painting a house in the Georgia Sea Islands in return for a couch, meals, and maybe eight bucks an hour.

road. I ended up sleeping outside a lot of nights and even taking gainful employment, painting a house in the Georgia Sea Islands in return for a couch, meals, and maybe eight bucks an hour. As Merle wrote, you learn things hoboing that they’ll never teach you in a classroom, and if any bright young folks are reading this, I recommend getting out there and seeing what happens. Despite what everybody seems to be saying, it’s not more dangerous now than it used to be. It was always chancy, but most people are pretty decent if you approach them right; the real world isn’t like the movies or the internet.

As Merle wrote, you learn things hoboing that they’ll never teach you in a classroom, and if any bright young folks are reading this, I recommend getting out there and seeing what happens. Despite what everybody seems to be saying, it’s not more dangerous now than it used to be. It was always chancy, but most people are pretty decent if you approach them right; the real world isn’t like the movies or the internet. walking the last five miles into Southport, North Carolina. On the edge of town I passed a gas station and a skinny old guy came running out, gestured to the guitar I had slung over my shoulder, and asked, “Can you play that thing?”

walking the last five miles into Southport, North Carolina. On the edge of town I passed a gas station and a skinny old guy came running out, gestured to the guitar I had slung over my shoulder, and asked, “Can you play that thing?” and said, “You could have any of them, if you want…” Which I didn’t, but it felt honky-tonk.

and said, “You could have any of them, if you want…” Which I didn’t, but it felt honky-tonk. I’d actually cemented a multi-year relationship by responding to my date’s query, “What do you think about Merle Haggard?” by saying, “Merle Haggard is God.” And I’d amassed a pretty fair collection of his LPs. But nothing prepared me for how good he was live. It was a comfortably loose show, with great playing and singing, and Merle doing imitations of other singers, and Bonnie Owens adding harmony, and since the gig was in Shreveport, James Burton was hanging out backstage. It was a night to remember, and he’s still one of my all-time favorites.

I’d actually cemented a multi-year relationship by responding to my date’s query, “What do you think about Merle Haggard?” by saying, “Merle Haggard is God.” And I’d amassed a pretty fair collection of his LPs. But nothing prepared me for how good he was live. It was a comfortably loose show, with great playing and singing, and Merle doing imitations of other singers, and Bonnie Owens adding harmony, and since the gig was in Shreveport, James Burton was hanging out backstage. It was a night to remember, and he’s still one of my all-time favorites.