This is another in the long list of Woody Guthrie songs I’ve known since my elementary school years, and stands out for me in part because Dave Van Ronk recorded it on his second Philo album, in a period when we were spending a lot of time together. I was  surprised, because Dave hadn’t recorded any of Woody’s other songs, and I didn’t think of them as his kind of music.

surprised, because Dave hadn’t recorded any of Woody’s other songs, and I didn’t think of them as his kind of music.

Of course, he knew a bunch of those songs, because everybody did, but he also was of the generation and sect that had tended to shy away from Woody’s work, in part because it had been canonized by the previous generation of folk revivalists, and in part because he tended not to like “country” or other white southern “old-time” styles. He’d come up in the Civil Rights era, and although he liked the members of the New Lost City Ramblers as individuals, he associated much of their repertoire with a culture he considered retrograde and dangerous. As he once put it, “It’s the soundtrack of the lynch mobs, and I want nothing to do with it.”

Obviously, that’s an oversimplification, but it’s not wrong: some canonical old-time players performed under the sponsorship of the Ku Klux Klan, and many more were solid segregationists and, if around today, would be solid MAGA voters. Others, of course, were populists (the left-wing kind), or connected with various union or farmer organizations he thoroughly supported, and Guthrie was firmly on the left, so that wasn’t a specific problem, but it still wasn’t his kind of music — and, again, there was the problem of canonization. He thought Dylan was, on the whole, a better songwriter than Guthrie; that Joni Mitchell was, on the whole, a better songwriter than Dylan; and that Cole Porter was a better songwriter than any of them.

So I was surprised he recorded this one. Part of the explanation was that he was in a mood to pay tribute. He recorded this on the same album as Tom Paxton’s “Did You Hear John Hurt?” and followed it with Dylan’s “Song to Woody.”But he also just thought it was a damn good song.

This is another of the songs Woody wrote in 1941 on commission for the Department of the Interior, celebrating the Bonneville Power Administration, and appearing on the soundtrack of a documentary film promoting dam-building and rural electrification. I’ve posted some others (“Grand Coulee Dam,” “Roll On, Columbia“), but this one feels more timely, due to the current war on immigrants, or migrants, or just poor people — and that’s not just a MAGA problem; the Democrats and lots of other parties in lots of other countries are getting votes by framing migrants as a problem, rather than as people trying to escape and solve problems.

This is another of the songs Woody wrote in 1941 on commission for the Department of the Interior, celebrating the Bonneville Power Administration, and appearing on the soundtrack of a documentary film promoting dam-building and rural electrification. I’ve posted some others (“Grand Coulee Dam,” “Roll On, Columbia“), but this one feels more timely, due to the current war on immigrants, or migrants, or just poor people — and that’s not just a MAGA problem; the Democrats and lots of other parties in lots of other countries are getting votes by framing migrants as a problem, rather than as people trying to escape and solve problems.

I’ve written a lot about that in my blog about immigration, borders, and related issues, and will keep writing about it, because it’s the central issue of our time, along with the climate changes that are making mass immigration increasingly vital for many millions of people.

For this post, I’ll just add that my chording for this song is consciously idiosyncratic; my basic idea was just to stay on the Dm chord, adding other notes where they seemed to fit. You might call that approach modal, but I see no need to get fancy about the terminology; my inspiration was a piece Pete Seeger wrote about the virtues of simplicity, in which he mentioned that he had finally got the point of playing “Old Joe Clark” with a single chord all the way through. I’m also headed that way with “Nottamun Town”/”Masters of War,” though, as with this one, I sometimes throw in an extra note or switch to another chord if it feels right. More and more, on songs like these, I’ve been thinking of the guitar as an accompanying instrument, following the voice, rather than as providing a solid foundation. And it’s not coincidental that in both of my examples, I’m working from a minor chord, while a lot of old-time players would have played major chords, though sometimes singing the minor third. And, in case that sounds technical… I know lots of people, including Dave Van Ronk, who could easily point out where someone was singing a minor third while playing the major, but I’m not one of them. I write music history, but I’m not that kind of musicologist, and the bottom line on this arrangement is that it’s what feels right to me these days.

musically, Butch supplied a bunch of the best songs in Joe’s repertoire, and I learned a bunch of them, though I only performed a couple onstage.

musically, Butch supplied a bunch of the best songs in Joe’s repertoire, and I learned a bunch of them, though I only performed a couple onstage. Willie Dixon wrote this one and gave it to Muddy, and it changed Muddy’s career. It was by far his biggest hit, but that wasn’t the only thing; it was fundamentally different from the deep Delta blues style that originally put him on the map in Chicago. For one thing, his early hits featured his ferociously amplified slide guitar, but he didn’t play on this one. For another thing, it was clever, and funny.

Willie Dixon wrote this one and gave it to Muddy, and it changed Muddy’s career. It was by far his biggest hit, but that wasn’t the only thing; it was fundamentally different from the deep Delta blues style that originally put him on the map in Chicago. For one thing, his early hits featured his ferociously amplified slide guitar, but he didn’t play on this one. For another thing, it was clever, and funny. transforming my ideas about what I wanted to be playing and how, and why.

transforming my ideas about what I wanted to be playing and how, and why. — pretty much straight-up life story except that he was just doing a three-year stretch in San Quentin, not “life without parole.”

— pretty much straight-up life story except that he was just doing a three-year stretch in San Quentin, not “life without parole.” While researching this post, I learned that this was the theme song to a movie, Killers Three, which also marked Merle’s acting debut –though his appearance is limited to two or three lines and some bemused head-shaking. The movie includes a couple of other songs by him and his wife (briefly) and singing partner (long-term), Bonnie Owens, but this one is just played as an instrumental under the opening credits. The movie is a complicated tale of bootlegging, romance, and a nice boy gone wrong, produced, co-written, and co-starring Dick Clark, of American Bandstand fame. It’s up on Youtube. I’m not recommending it.

While researching this post, I learned that this was the theme song to a movie, Killers Three, which also marked Merle’s acting debut –though his appearance is limited to two or three lines and some bemused head-shaking. The movie includes a couple of other songs by him and his wife (briefly) and singing partner (long-term), Bonnie Owens, but this one is just played as an instrumental under the opening credits. The movie is a complicated tale of bootlegging, romance, and a nice boy gone wrong, produced, co-written, and co-starring Dick Clark, of American Bandstand fame. It’s up on Youtube. I’m not recommending it. all the time, and I had some harmonicas, so Jasper played rhythm guitar and I played harmonica and sang, and by the end of the week I’d made enough money that I could buy a guitar.

all the time, and I had some harmonicas, so Jasper played rhythm guitar and I played harmonica and sang, and by the end of the week I’d made enough money that I could buy a guitar. I always liked Jimmy Reed’s recordings, because he sounded so relaxed, and I loved his weird harmonica playing. I never tried to play like him — honestly, I never worked on playing harmonica like anybody, except briefly on some Robert Lee McCoy licks, which I no longer remember, and I really should buckle down and study…

I always liked Jimmy Reed’s recordings, because he sounded so relaxed, and I loved his weird harmonica playing. I never tried to play like him — honestly, I never worked on playing harmonica like anybody, except briefly on some Robert Lee McCoy licks, which I no longer remember, and I really should buckle down and study… As for the song, I feel like I’ve known it forever. I don’t remember when I got the record I learned it from, but it would have been back when my mom was still required for that purpose, and fortunately was more than willing to feed myhabit. I just checked and found that the LP I had was issued in 1967, as the first of a cheaper line of Folkways records that had glossy covers and lacked the enclosed booklets that were standard in their main line of albums.

As for the song, I feel like I’ve known it forever. I don’t remember when I got the record I learned it from, but it would have been back when my mom was still required for that purpose, and fortunately was more than willing to feed myhabit. I just checked and found that the LP I had was issued in 1967, as the first of a cheaper line of Folkways records that had glossy covers and lacked the enclosed booklets that were standard in their main line of albums. The patriotism makes some sense in the context of World War II, but I grew up in the Vietnam era and was never much taken by lines like “there stands a towering fortress in the fight for Uncle Sam.” And that was before I read Cadillac Desert, which left me permanently disenamored with the big Western dam projects. And the defense of fortress USA has gotten uglier and uglier through most of my lifetime, and if I sometimes feel a twinge of nostalgia for Woody’s patriotism, for the idea of a “simpler time,” I just have to reread my post for “Roll On, Columbia,” which recalls the generally omitted verse celebrating the genocide of northwestern Natives.

The patriotism makes some sense in the context of World War II, but I grew up in the Vietnam era and was never much taken by lines like “there stands a towering fortress in the fight for Uncle Sam.” And that was before I read Cadillac Desert, which left me permanently disenamored with the big Western dam projects. And the defense of fortress USA has gotten uglier and uglier through most of my lifetime, and if I sometimes feel a twinge of nostalgia for Woody’s patriotism, for the idea of a “simpler time,” I just have to reread my post for “Roll On, Columbia,” which recalls the generally omitted verse celebrating the genocide of northwestern Natives. Of course, the song has nothing to do with mills. It’s a bitter, drunken man’s meditation on a messed-up relationship, which he’s messing up further as he sings. At least, that’s what I hear, and by now I hear it as a prophecy of sorts, because Bill messed up a bunch of relationships in the process of drinking himself to death. But he also wasn’t this guy, who, under the cloak of misogyny and self-loathing, is a romantic fiction.

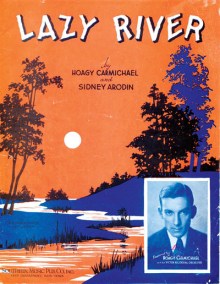

Of course, the song has nothing to do with mills. It’s a bitter, drunken man’s meditation on a messed-up relationship, which he’s messing up further as he sings. At least, that’s what I hear, and by now I hear it as a prophecy of sorts, because Bill messed up a bunch of relationships in the process of drinking himself to death. But he also wasn’t this guy, who, under the cloak of misogyny and self-loathing, is a romantic fiction. As part of that process, I worked on singing some difficult melodies, and a lot of my favorite difficult melodies were composed by Hoagy Carmichael. “Stardust,” of course, and yes, I worked on singing that, but promise never to do it in public–and fortunately for everybody, I never even attempted “Skylark” or “Baltimore Oriole.” But I did try “Lazy River,” which felt more approachable, especially when I listened to Carmichael sing it. To be fair, anything sounds more approachable when Carmichael sings it; he had a gift for intricate melodies, and also for simplifying them when he sang them himself. But that’s a subject for another day.

As part of that process, I worked on singing some difficult melodies, and a lot of my favorite difficult melodies were composed by Hoagy Carmichael. “Stardust,” of course, and yes, I worked on singing that, but promise never to do it in public–and fortunately for everybody, I never even attempted “Skylark” or “Baltimore Oriole.” But I did try “Lazy River,” which felt more approachable, especially when I listened to Carmichael sing it. To be fair, anything sounds more approachable when Carmichael sings it; he had a gift for intricate melodies, and also for simplifying them when he sang them himself. But that’s a subject for another day. Buffett said this song was inspired by a legendary figure in Chicago, Eddie Balchowsky, who worked as a janitor at a club called the Quiet Knight, and painted, and played classical piano, and sang songs of the Spanish Civil War. I got to hang out with Eddie for a few days in Vancouver, when Utah Phillips brought him there to play at the Folk Festival. He had lost the lower part of his right arm fighting with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in that war, but could play plenty of music with his left, and he had endless stories. Utah wrote a fine song about him, “

Buffett said this song was inspired by a legendary figure in Chicago, Eddie Balchowsky, who worked as a janitor at a club called the Quiet Knight, and painted, and played classical piano, and sang songs of the Spanish Civil War. I got to hang out with Eddie for a few days in Vancouver, when Utah Phillips brought him there to play at the Folk Festival. He had lost the lower part of his right arm fighting with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in that war, but could play plenty of music with his left, and he had endless stories. Utah wrote a fine song about him, “