I have no idea how I ended up with a copy of Kris Kristofferson’s first album — I was buying hardly any country, or rock, or pop at that point — but however it came into my hands, I was instantly hooked. The writing was like nothing I’d ever heard: a perfect combination of hip, smart, soulful, literary, and simple as a great country song . It matched Kris’s unique background: Vietnam, Oxford University, flying helicopters to oil rigs, emptying ashtrays at Columbia’s Nashville studio. But I didn’t know that at the time; I just knew how much I loved his writing. In retrospect some of the songs feel a little over-romantic — in a 19th century literary sense — but I was the right age for that, and others have held up as well as any songs I know. I’ll probably get to “Me and Bobby McGee” before this project is over, because overdone as it is, it’s a great song; and I don’t think I can write about busking in Norway without doing “Help Me Make It Through the Night”; and I don’t know many better phrases than “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down,” and have a soft spot for “Just the Other Side of Nowhere”…

. It matched Kris’s unique background: Vietnam, Oxford University, flying helicopters to oil rigs, emptying ashtrays at Columbia’s Nashville studio. But I didn’t know that at the time; I just knew how much I loved his writing. In retrospect some of the songs feel a little over-romantic — in a 19th century literary sense — but I was the right age for that, and others have held up as well as any songs I know. I’ll probably get to “Me and Bobby McGee” before this project is over, because overdone as it is, it’s a great song; and I don’t think I can write about busking in Norway without doing “Help Me Make It Through the Night”; and I don’t know many better phrases than “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down,” and have a soft spot for “Just the Other Side of Nowhere”…

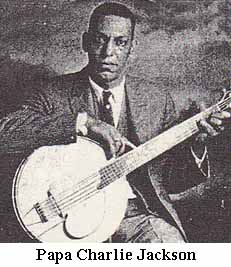

But my favorite to play and sing was always “Best of All Possible Worlds,” because it came along just when I was getting into Jim Kweskin and Willie McTell and all those guys who played rural ragtime circle-of-fifths tunes, and I figured out that a riff from McTell’s “Kill It, Kid” would fit perfectly with Kristofferson’s song. Plus, I never heard anyone else do this one, unlike all the other Kristofferson songs I liked, which were mostly covered to death.

Also, obviously, I love the story, and the wry humor:

They finally came and told me they were gonna set me free,

And that I’d be leaving town if I knew what was good for me.

I said, “It’s nice to learn that everybody’s so concerned about my health.”

I was lucky enough to meet Kris a couple of times, and interview him, and he was one of the most likeable people in the music business. He carried a band made up of songwriters who enjoyed hanging out and playing together, including Billy Swan and Donnie Fritts, and I once came back to the dressing room and asked Swan,  who was acting as the bandleader, if he had a set list for the show I’d just heard, and behind me Kris quietly said, “You got a pen?” And then, while his band drank beer and relaxed, he wrote out the set for me. That may not sound like much, but headliners don’t typically act that way — not to mention headliners who are also movie stars. But he has always been atypical, in a lot of ways: that night, he’d done a country set about the Nicaraguan revolution, including a moment when he named Sandino, Che Guevara, and other Latin American revolutionary heroes, and the bandmembers pumped fists in the air and yelled “¡Presente!” after each name. (The album was called Third World Warrior. It wasn’t a great record, but it was heartfelt and a very unusual project to be touring around county fairs in middle America in 1990.)

who was acting as the bandleader, if he had a set list for the show I’d just heard, and behind me Kris quietly said, “You got a pen?” And then, while his band drank beer and relaxed, he wrote out the set for me. That may not sound like much, but headliners don’t typically act that way — not to mention headliners who are also movie stars. But he has always been atypical, in a lot of ways: that night, he’d done a country set about the Nicaraguan revolution, including a moment when he named Sandino, Che Guevara, and other Latin American revolutionary heroes, and the bandmembers pumped fists in the air and yelled “¡Presente!” after each name. (The album was called Third World Warrior. It wasn’t a great record, but it was heartfelt and a very unusual project to be touring around county fairs in middle America in 1990.)

It was Kris’s first album, though, and his follow-up, The Silver-Tongued Devil, that changed the course of country music, and if anyone reading this hasn’t heard either, or both, you’ve got a treat in store.

She was, presumably, one of the “yellow women” whose doorbells the singer would no longer be ringing. At the time I had no idea what the word “yellow” meant in that context, though I’m pretty sure I understood him to be talking about prostitutes.

She was, presumably, one of the “yellow women” whose doorbells the singer would no longer be ringing. At the time I had no idea what the word “yellow” meant in that context, though I’m pretty sure I understood him to be talking about prostitutes. — about light-skinned black women. And that, in turn, leads into the complex and brutal history of colonialism and slavery, and in particular the long history of white men publicly decrying the idea of white-black sexual relations while privately indulging by means of rape and economic coercion… and the pervasive double standard whereby women who fail to remain “pure,” whether voluntarily or not, get blamed for being temptresses, or loose, or whores.

— about light-skinned black women. And that, in turn, leads into the complex and brutal history of colonialism and slavery, and in particular the long history of white men publicly decrying the idea of white-black sexual relations while privately indulging by means of rape and economic coercion… and the pervasive double standard whereby women who fail to remain “pure,” whether voluntarily or not, get blamed for being temptresses, or loose, or whores. old-time country blues recordings; and I guess I was already something of a loner and a contrarian by age five, more attuned to Woody Guthrie than to the perky collegiate approach. In any case, I missed the Kingston Trio, the Chad Mitchell Trio, the Brothers Four, and only heard Peter, Paul and Mary because my little sister liked them, but never listened to them voluntarily.

old-time country blues recordings; and I guess I was already something of a loner and a contrarian by age five, more attuned to Woody Guthrie than to the perky collegiate approach. In any case, I missed the Kingston Trio, the Chad Mitchell Trio, the Brothers Four, and only heard Peter, Paul and Mary because my little sister liked them, but never listened to them voluntarily. and fooling around with my own variation of the bass part, because it was fun. And then there was José Feliciano…

and fooling around with my own variation of the bass part, because it was fun. And then there was José Feliciano… I never heard him during my childhood, because he didn’t like to play in front of people. But he had all the right records, and there were a few years when I guess he didn’t have a regular place to live, or anyway a place for the records, so he left them with us. That’s where I first heard Joseph Spence, and Jelly Roll Morton, and he had all the first round of country blues reissue albums, starting with the canonical, seminal The Country Blues, compiled by Samuel B. Charters.

I never heard him during my childhood, because he didn’t like to play in front of people. But he had all the right records, and there were a few years when I guess he didn’t have a regular place to live, or anyway a place for the records, so he left them with us. That’s where I first heard Joseph Spence, and Jelly Roll Morton, and he had all the first round of country blues reissue albums, starting with the canonical, seminal The Country Blues, compiled by Samuel B. Charters. that they rushed out their own anthology, Really! The Country Blues, which didn’t include any urban artists. It was great, too, and my brother had both of them, so I also got to hear Tommy Johnson’s “Maggie Campbell” and Skip James singing “Devil Got My Woman.”

that they rushed out their own anthology, Really! The Country Blues, which didn’t include any urban artists. It was great, too, and my brother had both of them, so I also got to hear Tommy Johnson’s “Maggie Campbell” and Skip James singing “Devil Got My Woman.” , John Held, Jr. The concept behind the book was to preserve the songs men used to sing in saloons, which were endangered due to Prohibition — which had not ended drinking, by any means, but had ended loud singing around the piano in the local bar. (Held also illustrated a book called The Saloon in the Home, or a Garden of Rumblossoms, which purported to present an evenhanded debate for and against Prohibition, the “pro” side represented by severe tracts on temperance and the dangers of alcohol, and the “anti” represented by cocktail recipes.)

, John Held, Jr. The concept behind the book was to preserve the songs men used to sing in saloons, which were endangered due to Prohibition — which had not ended drinking, by any means, but had ended loud singing around the piano in the local bar. (Held also illustrated a book called The Saloon in the Home, or a Garden of Rumblossoms, which purported to present an evenhanded debate for and against Prohibition, the “pro” side represented by severe tracts on temperance and the dangers of alcohol, and the “anti” represented by cocktail recipes.) at a map of Liberia, and found a Robertsport, which sounded enough like “Robert’s Falls” that I called Dave and asked if the song was Liberian, and indeed it was.

at a map of Liberia, and found a Robertsport, which sounded enough like “Robert’s Falls” that I called Dave and asked if the song was Liberian, and indeed it was.

him in concert. It was a split bill with Patrick Sky at Jordan Hall, with Patrick on first, and he and Dave had clearly been doing some drinking ahead of time, but both were in great form. Patrick’s set included “The Pope,” off Songs That Made America Famous, which caused my mother literally to fall out of her seat, she was laughing so hard. (The clincher was probably, “They know that they could never quibble/With a man who is infallibibble!”)

him in concert. It was a split bill with Patrick Sky at Jordan Hall, with Patrick on first, and he and Dave had clearly been doing some drinking ahead of time, but both were in great form. Patrick’s set included “The Pope,” off Songs That Made America Famous, which caused my mother literally to fall out of her seat, she was laughing so hard. (The clincher was probably, “They know that they could never quibble/With a man who is infallibibble!”) loved Dylan Thomas and always regretted that she had never seen one of his legendary, boozy, brilliant, hypnotic readings, walked out saying, “That must be what it was like to see Dylan Thomas.”

loved Dylan Thomas and always regretted that she had never seen one of his legendary, boozy, brilliant, hypnotic readings, walked out saying, “That must be what it was like to see Dylan Thomas.” and I’m guessing it was supposed to be the title song, since when I mentioned that album to him, Dave’s response was a pained grimace and the comment, “They even got the title wrong.” I never figured out why he disliked that album so much, and am convinced the problems were in the process rather than the result, since the result was one of his best records, with a terrific range of material, from old country blues to

and I’m guessing it was supposed to be the title song, since when I mentioned that album to him, Dave’s response was a pained grimace and the comment, “They even got the title wrong.” I never figured out why he disliked that album so much, and am convinced the problems were in the process rather than the result, since the result was one of his best records, with a terrific range of material, from old country blues to  Charley Jordan, recorded in 1930, but Dave sang different verses, changed the chorus, and set it to a guitar arrangement that bore no relation to Jordan’s. Unfortunately for those of us who enjoyed that arrangement, this was during a passing period of infatuation with open C tuning, and by the time I knew him he’d dropped it from his repertoire — when I asked him to teach me the chart, he said he couldn’t remember it. However, the obvious inspiration was Lemon Jefferson’s “Bad Luck Blues,” which is in standard tuning, so I copped that — not very well, for the first few decades, but four or five years ago I went through an intensive Blind Lemon period and figured out the nice move from C up to D in the opening riff.

Charley Jordan, recorded in 1930, but Dave sang different verses, changed the chorus, and set it to a guitar arrangement that bore no relation to Jordan’s. Unfortunately for those of us who enjoyed that arrangement, this was during a passing period of infatuation with open C tuning, and by the time I knew him he’d dropped it from his repertoire — when I asked him to teach me the chart, he said he couldn’t remember it. However, the obvious inspiration was Lemon Jefferson’s “Bad Luck Blues,” which is in standard tuning, so I copped that — not very well, for the first few decades, but four or five years ago I went through an intensive Blind Lemon period and figured out the nice move from C up to D in the opening riff.

sung in barrelhouses. I first heard it from Mississippi John Hurt, and still play pretty much his version, though I seem to have picked up some vocal inflections from Lead Belly, and wouldn’t be surprised if Jack Elliott gets in there as well.

sung in barrelhouses. I first heard it from Mississippi John Hurt, and still play pretty much his version, though I seem to have picked up some vocal inflections from Lead Belly, and wouldn’t be surprised if Jack Elliott gets in there as well. “my buddy” as the person who caught the singer kissing his wife, refers to “Uncle Bud,” a legendary figure of black folksong, and “kissing” would not have been the word used in barrelhouse performances. Zora Neale Hurston sings a common variant of “Uncle Bud” on a Library of Congress recording, and a typical verse goes:

“my buddy” as the person who caught the singer kissing his wife, refers to “Uncle Bud,” a legendary figure of black folksong, and “kissing” would not have been the word used in barrelhouse performances. Zora Neale Hurston sings a common variant of “Uncle Bud” on a Library of Congress recording, and a typical verse goes: I love the Sheiks, especially Lonnie Chatmon’s fiddling, but didn’t hear them until I was in my late teens or twenties, and had no idea who they were when I first heard this song on Doc Watson’s first album. I got the guitar part from Doc’s songbook, which provided tablature, and it may well have been the first piece I ever learned in open D tuning, and remains one of the few — I have trouble enough just keeping a guitar in tune, without attempting to retune it on a regular basis.

I love the Sheiks, especially Lonnie Chatmon’s fiddling, but didn’t hear them until I was in my late teens or twenties, and had no idea who they were when I first heard this song on Doc Watson’s first album. I got the guitar part from Doc’s songbook, which provided tablature, and it may well have been the first piece I ever learned in open D tuning, and remains one of the few — I have trouble enough just keeping a guitar in tune, without attempting to retune it on a regular basis. think was how much he reminded me of Doc, except quirkier.

think was how much he reminded me of Doc, except quirkier.