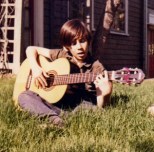

This is another cowboy song from Cisco Houston, off that first American Folk Songs album, which I’ve kept singing pretty regularly as a kind of apologia pro vita mia. Growing up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as the child of two professors, it was obvious that my roots were different from Woody’s or Cisco’s, or from all the heroes of the pirate and western sagas I liked to read. So this ballad about someone who looks like a city dude and talks educated English, but is nonetheless an authentic cowboy, had a special appeal.

I’m clearly not the only one who felt that way, since a lot of other singers have recorded this over the years, starting with Jules Verne Allen in 1928. Allen was one of the first genuine cowboys to record, and his name suggests the literary tastes that sent a lot of boys (and some girls) west in search of adventure. One of them was N. Howard “Jack” Thorpe, who first collected this song from someone named Randolph Reynolds on New Mexico’s Carrizozo Flats in 1890, and included it in Songs of the Cowboys, the first issued collection of cowboy songs, which he self-published in 1908.

I recently picked up a copy of Thorpe’s memoir, Pardner of the Wind, which explains that he was born in New York in 1867, the son of a wealthy lawyer, and grew up between there and summers in Newport, honing his riding skills by playing on a polo team with  Theodore Roosevelt. He went west in his teens, and by 1890 was a full-fledged cowboy, working as an “outside man,” which meant his job was to travel beyond the home ranch in search of cattle that had strayed into other herds. In the process, he was visiting all the other ranches and camps in southern New Mexico, and along the way he picked up a lot of songs — though he explains that most came it bits and pieces, a verse here and a verse there, and “many of the songs had to be dry-cleaned for unprintable words before they went to press.” He refers to this song as “The Educated Feller,” and writes, “It’s as typical of the range as ants in chuck wagon biscuits.

Theodore Roosevelt. He went west in his teens, and by 1890 was a full-fledged cowboy, working as an “outside man,” which meant his job was to travel beyond the home ranch in search of cattle that had strayed into other herds. In the process, he was visiting all the other ranches and camps in southern New Mexico, and along the way he picked up a lot of songs — though he explains that most came it bits and pieces, a verse here and a verse there, and “many of the songs had to be dry-cleaned for unprintable words before they went to press.” He refers to this song as “The Educated Feller,” and writes, “It’s as typical of the range as ants in chuck wagon biscuits.

were Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston, and if I’d had to pick one of them, it would probably have been Cisco. Part of the appeal was the warmth of his voice and the easy lope of his guitar, but more than that it was the songs: he liked songs that told stories, and he had an actor’s gift for making those stories come alive.

were Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston, and if I’d had to pick one of them, it would probably have been Cisco. Part of the appeal was the warmth of his voice and the easy lope of his guitar, but more than that it was the songs: he liked songs that told stories, and he had an actor’s gift for making those stories come alive.

as well as writing a good book of cowboy songs and verse, Ten Thousand Goddam Cattle, and making a bunch of recordings, and just being a hell of a fascinating person. She’s still very much around at age 95, and it’s well worth checking out her website, www.katydoodit.com, and browsing through her interviews, and film clips, and book projects.

as well as writing a good book of cowboy songs and verse, Ten Thousand Goddam Cattle, and making a bunch of recordings, and just being a hell of a fascinating person. She’s still very much around at age 95, and it’s well worth checking out her website, www.katydoodit.com, and browsing through her interviews, and film clips, and book projects. “Talking Union” was the title song of the Almanac Singers’ most popular album (back in the days when “album” meant literally that: a bound album of 78 records). As I mentioned in the last couple of posts, my first records included a bunch of left-wing 78 albums, including Talking Union, though that one was missing its cover and I only learned what it looked like about forty years later.

“Talking Union” was the title song of the Almanac Singers’ most popular album (back in the days when “album” meant literally that: a bound album of 78 records). As I mentioned in the last couple of posts, my first records included a bunch of left-wing 78 albums, including Talking Union, though that one was missing its cover and I only learned what it looked like about forty years later.

I helped form a steering committee when we put together the Boston Globe Freelancers Association under the auspices of the National Writers Union and led a walk-out of three hundred freelance writers, photographers, and designers who refused to sign a new and confiscatory contract. I was sorry to go, because I liked writing for the Globe, but I figured that after thirty years of singing union songs it was time to step up and be counted.

I helped form a steering committee when we put together the Boston Globe Freelancers Association under the auspices of the National Writers Union and led a walk-out of three hundred freelance writers, photographers, and designers who refused to sign a new and confiscatory contract. I was sorry to go, because I liked writing for the Globe, but I figured that after thirty years of singing union songs it was time to step up and be counted. It was on the one Almanac Singers’ album my grandparents had, which I eventually learned was called Talking Union — I didn’t know the title at the time because the cover had fallen off before it came into my hands.

It was on the one Almanac Singers’ album my grandparents had, which I eventually learned was called Talking Union — I didn’t know the title at the time because the cover had fallen off before it came into my hands. Many years later, when I was researching my

Many years later, when I was researching my

6, 33 1/3, 45, and 78. They wouldn’t let me play their records on it, but I had a few children’s folk LPs — one by Tom Glazer, and a couple of Everybody Sing! anthologies — and somehow I also ended up with my grandparents’ 78 albums.

6, 33 1/3, 45, and 78. They wouldn’t let me play their records on it, but I had a few children’s folk LPs — one by Tom Glazer, and a couple of Everybody Sing! anthologies — and somehow I also ended up with my grandparents’ 78 albums. but along with dozens of classical albums, they had the classic Communist record collection of the early 1940s: Paul Robeson, the Red Army Chorus, the International Brigades from the Spanish Civil War, Josh White, the Almanac Singers, and the Union Boys. The Union Boys wasn’t actually a group — it was just a bunch of singers who got together to record an album’s worth of songs about union organizing and the war effort, among them Pete Seeger, Burl Ives, Tom Glazer, Josh White, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, plus one side by Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston.

but along with dozens of classical albums, they had the classic Communist record collection of the early 1940s: Paul Robeson, the Red Army Chorus, the International Brigades from the Spanish Civil War, Josh White, the Almanac Singers, and the Union Boys. The Union Boys wasn’t actually a group — it was just a bunch of singers who got together to record an album’s worth of songs about union organizing and the war effort, among them Pete Seeger, Burl Ives, Tom Glazer, Josh White, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, plus one side by Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston. I played those records constantly and learned most of the songs, and these two were particular favorites. I suppose part of the appeal was the war — despite my parents’ pacifist leanings, I played with toy soldiers and dug trenches and all that kind of stuff, and it was exciting to sing about rolling into Berlin with your buddies from the union and going after Hitler. I didn’t understand all the words, of course — I don’t think I knew the meaning of either UAW or CIO — but thirty years later, when I helped organize a freelancer’s group at the Boston Globe under the auspices of the National Writers Union, I was particularly pleased that we were a subsection of the UAW. It kind of brought everything full circle, and felt like I’d stayed true to my early friends.

I played those records constantly and learned most of the songs, and these two were particular favorites. I suppose part of the appeal was the war — despite my parents’ pacifist leanings, I played with toy soldiers and dug trenches and all that kind of stuff, and it was exciting to sing about rolling into Berlin with your buddies from the union and going after Hitler. I didn’t understand all the words, of course — I don’t think I knew the meaning of either UAW or CIO — but thirty years later, when I helped organize a freelancer’s group at the Boston Globe under the auspices of the National Writers Union, I was particularly pleased that we were a subsection of the UAW. It kind of brought everything full circle, and felt like I’d stayed true to my early friends.