One of the pleasures of playing on the street with Rob was that I had a second voice on the choruses of my favorite Woody Guthrie – Cisco Houston duets. I’d spent the previous couple of years learning blues and other stuff that lent itself to fingerstyle guitar, but I never lost my taste for the Woody/Cisco sound, and it had even become a matter of principle for me. I felt like a lot of the blues revivalists I liked had started out with Woody, Cisco, and Pete Seeger, but abandoned that music when they got into blues, and I understood the temptation but didn’t want to give in to it.

and it had even become a matter of principle for me. I felt like a lot of the blues revivalists I liked had started out with Woody, Cisco, and Pete Seeger, but abandoned that music when they got into blues, and I understood the temptation but didn’t want to give in to it.

For one thing, I really like Woody Guthrie’s music — his guitar playing, his harmonica playing, his singing, even his fiddling — and he had good taste in songs. In a slightly alternate reality, if he hadn’t succumbed to Huntington’s disease, it is easy to imagine him at Newport in the 1960s jamming with other folk revival discoveries from the Southwest like Mance Lipscomb, who  had a similarly broad repertoire and similar experience playing a wide range of regional blues and dance tunes.

had a similarly broad repertoire and similar experience playing a wide range of regional blues and dance tunes.

For another thing, this was the music I started on, and it continues to feel natural in ways some of the styles I picked up later never will. I’m not saying I’m better at it (honestly, I could never make a flatpick behave the way I wanted) or that it’s better suited to a kid from Cambridge, Massachusetts, but I’ve been playing it since I was seven or eight years old, and it’s part of me.

For a third, people always liked it. I might think of it as less sophisticated, or less complex, or more hokey and folky than the blues and ragtime I was picking up from Van Ronk and afterwards, but whenever I played something like “Columbus Stockade,” there were a few people who reacted like, “OK, this I really like!” And not always the people I expected.

Plus, in a lot of moods, I’m one of those people myself. I like Jelly Roll Morton and Ornette Coleman, or Charley Poole and Merle Haggard, or Pablo Casals and Aretha Franklin for different reasons and in different moods, and I’m glad to be able to listen to all of them. So, as a matter of principle, I didn’t want the fact that I’d learned to play “Maple Leaf Rag” to mean I stopped playing “Columbus Stockade.”

Besides all of which, for most folk/roots musicians of roughly my generation this was a common language. Bill Morrissey and I used to sing these songs together and talked about doing some gigs with this repertoire, and I never asked Paul Geremia or Dave Van Ronk if they knew “Columbus Stockade,” but I’m sure they did, because we all did. Whatever our later musical journeys, this was where pretty much all of us started, and it remained a good foundation and a style we could all sing together.

Which brings me by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to the beginning of this post, and the pleasure of singing on the streets with a good partner, which I still get now and then, and which always makes me think of Woody and Cisco.

(If you haven’t read Jim Longhi’s book, Woody, Cisco, and Me, I recommend it enthusiastically and without reservation — to me, it is the ultimate evocation of those two men and what made them so special, including but by no means limited to the music.)

is from a session he did for the embryonic Atlantic Records in 1949, well before it became a powerhouse jazz and R&B label. In a long

is from a session he did for the embryonic Atlantic Records in 1949, well before it became a powerhouse jazz and R&B label. In a long  We went to the studio that same day, but he only wanted to play gospel songs. I said, “Oh, man, but we wanted some blues.” He said, “Well, I don’t sing blues anymore, I’ve found God.” I said, “But you make great blues music – this is not a bad thing – if you could just sing some blues.” “Well,” he said, “don’t put my name on it.” So I said, “OK, we’ll call you Barrelhouse Sammy.” So we made some blues records and they came out under that name until after he died, when we released them with his actual name. It would have been criminal not to let people know who he was.

We went to the studio that same day, but he only wanted to play gospel songs. I said, “Oh, man, but we wanted some blues.” He said, “Well, I don’t sing blues anymore, I’ve found God.” I said, “But you make great blues music – this is not a bad thing – if you could just sing some blues.” “Well,” he said, “don’t put my name on it.” So I said, “OK, we’ll call you Barrelhouse Sammy.” So we made some blues records and they came out under that name until after he died, when we released them with his actual name. It would have been criminal not to let people know who he was. guitar on most of his records, which meant I could never get his sound, and tuned it very low, which made it hard for me to pick up licks in those days before we had digital pitch-shifting.

guitar on most of his records, which meant I could never get his sound, and tuned it very low, which made it hard for me to pick up licks in those days before we had digital pitch-shifting. was Blues at Newport, and I put on this song, then played it for my mother, and we went to the concert, and that was that.

was Blues at Newport, and I put on this song, then played it for my mother, and we went to the concert, and that was that. I’ve made some minor changes as well, and picked up other bits here and there, but this is substantially Dave’s version, with the Blake guitar roll from that guy in Harvard Square.

I’ve made some minor changes as well, and picked up other bits here and there, but this is substantially Dave’s version, with the Blake guitar roll from that guy in Harvard Square. (There’s

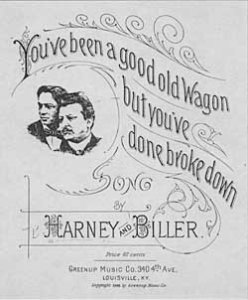

(There’s  For one, it was one of the handful of songs recorded by Ben Harney, one of the first ragtime composers. For another, it is a version of Harney’s first hit and one of the first published ragtime compositions, from 1895, which was titled “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon But You’ve Done Broke Down…” a familiar title to Van Ronk fans although, aside from the title line, which presumably inspired the

For one, it was one of the handful of songs recorded by Ben Harney, one of the first ragtime composers. For another, it is a version of Harney’s first hit and one of the first published ragtime compositions, from 1895, which was titled “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon But You’ve Done Broke Down…” a familiar title to Van Ronk fans although, aside from the title line, which presumably inspired the  As a teenager, I was naturally entranced, and Dave helped me work out the chords to “You’re Not the Only Oyster in the Stew,” and fairly soon thereafter I bought my first Fats Waller album, a two-LP set that included that, and “I Wish I Were Twins,” and “A Porter’s Love Song to a Chambermaid.” Most of the songs were too complicated for me to work out by ear, but by the time I’d finished that year with Van Ronk, this one was within my range, and it became a staple of my street sets when Rob and I began working in Harvard Square. It did not occur to me that there was anything markedly racial about the professions of the protagonists — I just thought of their jobs as a pretext for the cutely romantic lyric, which Rob notably parodied by adding his own variation on the lyrical theme: “I will do your chafing, if you’ll be my dish.”

As a teenager, I was naturally entranced, and Dave helped me work out the chords to “You’re Not the Only Oyster in the Stew,” and fairly soon thereafter I bought my first Fats Waller album, a two-LP set that included that, and “I Wish I Were Twins,” and “A Porter’s Love Song to a Chambermaid.” Most of the songs were too complicated for me to work out by ear, but by the time I’d finished that year with Van Ronk, this one was within my range, and it became a staple of my street sets when Rob and I began working in Harvard Square. It did not occur to me that there was anything markedly racial about the professions of the protagonists — I just thought of their jobs as a pretext for the cutely romantic lyric, which Rob notably parodied by adding his own variation on the lyrical theme: “I will do your chafing, if you’ll be my dish.” Andy Razaf was born Andreamentania Paul Razafinkeriefo on December 16, 1895 in Washington D.C., months after his mother had fled Madagascar because the government there had been overthrown. His father Henri Razafkeriefo… was killed after the French captured the island, exiled his aunt, the Queen and abolished the nobility.

Andy Razaf was born Andreamentania Paul Razafinkeriefo on December 16, 1895 in Washington D.C., months after his mother had fled Madagascar because the government there had been overthrown. His father Henri Razafkeriefo… was killed after the French captured the island, exiled his aunt, the Queen and abolished the nobility. By contrast, Judy Roderick’s version of”Miss Brown to You,” on an anthology of performances at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival, was a perfect match. I loved the way she sang and the way she played, and by then I had the chops to figure out her arrangement — or at least to figure out my take on her arrangement. (I haven’t heard her version in years, and won’t vouch for my accuracy.) It’s a nice, easy-swinging, guitar-friendly chart, and though it probably has some wrong chords by jazz standards, it’s fun to play and sing over.

By contrast, Judy Roderick’s version of”Miss Brown to You,” on an anthology of performances at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival, was a perfect match. I loved the way she sang and the way she played, and by then I had the chops to figure out her arrangement — or at least to figure out my take on her arrangement. (I haven’t heard her version in years, and won’t vouch for my accuracy.) It’s a nice, easy-swinging, guitar-friendly chart, and though it probably has some wrong chords by jazz standards, it’s fun to play and sing over. She made two LPs, but I don’t think either gave a sense of how good she could be — Woman Blue felt kind of low-key to me and Ain’t Nothing But the Blues surrounded her with a dixieland band that interfered rather than supporting her. But two of the Newport tracks, “Miss Brown to You” and “

She made two LPs, but I don’t think either gave a sense of how good she could be — Woman Blue felt kind of low-key to me and Ain’t Nothing But the Blues surrounded her with a dixieland band that interfered rather than supporting her. But two of the Newport tracks, “Miss Brown to You” and “ about Henry rather than Emily Brown: “Mister Brown to you.” I’m not going to say her version cuts Holiday’s, but it was way more accessible to me as a player, and for a while it became a staple of my repertoire.

about Henry rather than Emily Brown: “Mister Brown to you.” I’m not going to say her version cuts Holiday’s, but it was way more accessible to me as a player, and for a while it became a staple of my repertoire. Unitarian church on the corner of Church Street in Harvard Square. They even had free coffee, cider, and cookies, and I auditioned to play there but didn’t make the grade, so I worked my way into the inner circle by washing dishes in the kitchen when I wasn’t interested in the musician who happened to be playing.

Unitarian church on the corner of Church Street in Harvard Square. They even had free coffee, cider, and cookies, and I auditioned to play there but didn’t make the grade, so I worked my way into the inner circle by washing dishes in the kitchen when I wasn’t interested in the musician who happened to be playing. Since my year with Dave had primed me to play more swing standards, Guy seemed like the obvious next stop, and when I got to Cambridge I set up a lesson with him. The first thing he said was, “Name any standard, name any key.” I called “Sweet Georgia Brown” in Eb, and he ripped off a bunch of improvised choruses. That was the goal: to be able to improvise fully-formed fingerstyle arrangements freely, in any key, on any tune, like a jazz pianist — and he’d made it.

Since my year with Dave had primed me to play more swing standards, Guy seemed like the obvious next stop, and when I got to Cambridge I set up a lesson with him. The first thing he said was, “Name any standard, name any key.” I called “Sweet Georgia Brown” in Eb, and he ripped off a bunch of improvised choruses. That was the goal: to be able to improvise fully-formed fingerstyle arrangements freely, in any key, on any tune, like a jazz pianist — and he’d made it. rst hit was about a boy and girl falling asleep at the movies and waking up to the realization that no one would believe them and their reputations were shot. So, where to go with that?

rst hit was about a boy and girl falling asleep at the movies and waking up to the realization that no one would believe them and their reputations were shot. So, where to go with that? Producers who had grown up in a different world didn’t understand the teen market but desperately wanted to cash in, so they set hundreds of young songwriters and singers loose to experiment, and although most of the results were less than stellar, the naked attempt to express teen attitudes and feelings succeeded to a degree that is kind of amazing, though by no means always pretty.

Producers who had grown up in a different world didn’t understand the teen market but desperately wanted to cash in, so they set hundreds of young songwriters and singers loose to experiment, and although most of the results were less than stellar, the naked attempt to express teen attitudes and feelings succeeded to a degree that is kind of amazing, though by no means always pretty. Louvin Brothers — but I’m still struck by the uniqueness of their sound. The Delmores and Monroes had plenty of blues and drive in their music, but there was something different about the Everlys. Part of it was certainly their guitar playing, with its terrific simplicity and rhythmic power. And part of it, for me at least, was the attitude: they weren’t singing about country concerns, they were singing about teen concerns, and they were clever and funny.

Louvin Brothers — but I’m still struck by the uniqueness of their sound. The Delmores and Monroes had plenty of blues and drive in their music, but there was something different about the Everlys. Part of it was certainly their guitar playing, with its terrific simplicity and rhythmic power. And part of it, for me at least, was the attitude: they weren’t singing about country concerns, they were singing about teen concerns, and they were clever and funny. time for a few years, but by the end of the decade they were getting some country hits, and in 1957 they took off when the Everlys cut a song that had been turned down by some thirty country artists, called “Bye, Bye Love.”

time for a few years, but by the end of the decade they were getting some country hits, and in 1957 they took off when the Everlys cut a song that had been turned down by some thirty country artists, called “Bye, Bye Love.”