Elijah Wald – Dave Van Ronk Listener's Guide

[Home] [Bio] [Jelly Roll Blues] [Robert Johnson] [Dave Van Ronk] [Narcocorrido] [Dylan Goes Electric] [Beatles/Pop book] [The Dozens] [The Blues] [Josh White] [Hitchhiking] [Other writing] [Musical projects] [Joseph Spence]

Dave Van Ronk was one of my earliest influences and dearest friends. I lived with his albums for years before I made the pilgrimage to Greenwich Village and started learning guitar from him, eating his fabulous cooking, imbibing his endlessly wise and amusing soliloquies, listening to the jazz records he would put on late at night, and drinking far less than my share of the Jameson's Irish whiskey before finally crashing on his couch or stumbling out into the dawn.

Dave Van Ronk was one of my earliest influences and dearest friends. I lived with his albums for years before I made the pilgrimage to Greenwich Village and started learning guitar from him, eating his fabulous cooking, imbibing his endlessly wise and amusing soliloquies, listening to the jazz records he would put on late at night, and drinking far less than my share of the Jameson's Irish whiskey before finally crashing on his couch or stumbling out into the dawn.

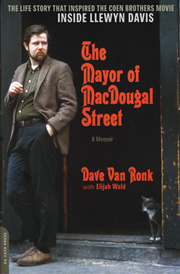

Dave rarely played any of his own records, and when he did he preferred to listen to the ones with sidemen, since he could enjoy what they were doing rather than hear what he wished he could redo--but over the years he occasionally commented on what he had committed to vinyl, and I've included some of those comments along with my opinions on a body of work I know better than any other and return to with pleasure. Most of his quotes are from our book, The Mayor of MacDougal Street, now available in a new edition because the Coen Brothers have used it as a partial inspiration for their latest film, Inside Llewyn Davis.

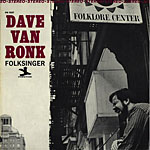

The albums are arranged in chronological order with a few relevant interpolations, and all are now available for download from the usual sites--the new wave of interest persuaded the megaconglomerate that now owns most of his 1960s work to go into the vaults and digitize everything. I have tried to provide rough précises of all his major releases, but anyone who wants a complete list with full track listenings should also consult the comprehensive discography compiled by Stefan Wirz. For newcomers who want to get a sense of what all the fuss is about without exploring the full oeuvre, the place to start remains Folksinger, the album with which Dave defined his musical aesthetic (and the source for a couple of songs in the movie), followed bySunday Street, the album that defined his mature approach in the 1970s. But there's plenty more, some of it extending the styles showcased on those albums, some showing other facets of his work.

Dave Van Ronk Sings Ballads, Blues and a Spiritual (Folkways, 1959)

Dave Van Ronk Sings Ballads, Blues and a Spiritual (Folkways, 1959)

Dave always referred to this record as "Archie Andrews sings the blues," which is not quite fair but suggests how much he developed in the next few years. I particularly like his one original song on it, "If You Leave Me Pretty Mama," but would agree that his later albums are better.

Foc'sle Songs and Shanties, sung by Paul Clayton and the Foc'sle Singers (Folkways, 1959)

This is a good example of how different the folk scene was in the late 1950s, since someone like Dave could end up as the most distinctive voice on an album like this. He was the one genuine seaman in the chorus, and his voice has the raspy power of a real old capstan shanty singer. He sings lead on four songs, but in some ways what I most enjoy is hearing him hitting high, raw harmonies behind the other guys. Along with a couple of a cappella songs I put out on the Mayor of MacDougal Street CD, this gives a sense of Dave's musical roots in the Irish songs his grandmother used to sing.

This is a good example of how different the folk scene was in the late 1950s, since someone like Dave could end up as the most distinctive voice on an album like this. He was the one genuine seaman in the chorus, and his voice has the raspy power of a real old capstan shanty singer. He sings lead on four songs, but in some ways what I most enjoy is hearing him hitting high, raw harmonies behind the other guys. Along with a couple of a cappella songs I put out on the Mayor of MacDougal Street CD, this gives a sense of Dave's musical roots in the Irish songs his grandmother used to sing.

Van Ronk Sings (Folkways, 1961)

Van Ronk Sings (Folkways, 1961)

A much better record than his first, in part because Dave was working a lot and developing very quickly, and in part because on a lot of songs he fell back on his trad jazz chops. "Sweet Substitute" is a lovely reading of a Jelly Roll Morton song, "Yas, Yas, Yas" was picked up from the singing of the Bahamian Blind Blake, and "Tell Old Bill" gives a sense of Van Ronk at his early, shouting best. Still part of the prehistory, but a strong part, and I know a couple of people who continue to consider this his greatest work. (They are wrong, but their high opinion indicates how influential this album was in its moment.)

Dave's Folkways material has been extensively mined for the new three-disc set from Smithsonian/ Folkways, Down in Washington Square, discussed at slightly greater length below.

Dave Van Ronk: Folksinger

(Prestige 1963, now included on the CD titled Inside Dave Van Ronk) This was the first great Van Ronk album and his defining musical statement before "Sunday Street" in the 1970s. His singing had become much more subtle, still raspy but often falling to a gruffly sensitive whisper, and his guitar playing set a standard for tone, taste, and astute arranging for several generations.

Dave Van Ronk: Folksinger

(Prestige 1963, now included on the CD titled Inside Dave Van Ronk) This was the first great Van Ronk album and his defining musical statement before "Sunday Street" in the 1970s. His singing had become much more subtle, still raspy but often falling to a gruffly sensitive whisper, and his guitar playing set a standard for tone, taste, and astute arranging for several generations. "Cocaine Blues" became his signature song for a while and still sounds great, though for guitarists the masterpiece was probably "Come Back Baby," an arrangement that for many years was learned by pretty much anyone interested in acoustic blues (Dave credited it to his friend Dave Woods, and I'd love to hear how Woods played it). Other great performances include "Hang Me, Oh, Hang Me," which is now featured in Llewyn Davis, "He Was a Friend of Mine," one of Dave's most hauntingly beautiful vocals, and his wry reading of Bessie Smith's "You've Been a Good Old Wagon." Also a lovely little oddity he picked up from a collection of Liberian cafe music, "Chicken Is Nice," and another oddity from who knows where, "Mr. Noah." What can I say? Not all the songs are up to those standards, but I love this record, always have, always will. Every time I come back to it, I'm amazed at the subtlety and taste with which he reshaped older blues styles to fit his own skills and temperament. To this day, most white blues performers--indeed, by now most blues players of any background--tend to sound like they are trying to act the part of black southerners from a previous era. Dave was one of the very few to come up with a style that drew from the tradition but was completely unique and personal. And those guitar arrangements... he always considered himself primarily a singer, and I agree, but no one ever created more brilliantly understated accompaniments. He loved old blues, but knew jazz very well and also drew on a range of other vernacular styles, and he put it all together in a new way without losing the simple power of his sources.

"Cocaine Blues" became his signature song for a while and still sounds great, though for guitarists the masterpiece was probably "Come Back Baby," an arrangement that for many years was learned by pretty much anyone interested in acoustic blues (Dave credited it to his friend Dave Woods, and I'd love to hear how Woods played it). Other great performances include "Hang Me, Oh, Hang Me," which is now featured in Llewyn Davis, "He Was a Friend of Mine," one of Dave's most hauntingly beautiful vocals, and his wry reading of Bessie Smith's "You've Been a Good Old Wagon." Also a lovely little oddity he picked up from a collection of Liberian cafe music, "Chicken Is Nice," and another oddity from who knows where, "Mr. Noah." What can I say? Not all the songs are up to those standards, but I love this record, always have, always will. Every time I come back to it, I'm amazed at the subtlety and taste with which he reshaped older blues styles to fit his own skills and temperament. To this day, most white blues performers--indeed, by now most blues players of any background--tend to sound like they are trying to act the part of black southerners from a previous era. Dave was one of the very few to come up with a style that drew from the tradition but was completely unique and personal. And those guitar arrangements... he always considered himself primarily a singer, and I agree, but no one ever created more brilliantly understated accompaniments. He loved old blues, but knew jazz very well and also drew on a range of other vernacular styles, and he put it all together in a new way without losing the simple power of his sources.

In the Tradition (Prestige, 1963)

In the Tradition (Prestige, 1963)

Half of the tracks on this one feature Dave singing with a trad jazz band, which is what he did before he got into folk and blues. It's a serviceable band, and he shouts over it enthusiastically, but basically his shouting style was a throwback both personally and historically. As he said, "I enjoyed making that record, but...good as that music may have been, there was no question but that its time had passed." He had rethought his singing style to fit the spare settings he provided on guitar, and the guitar-accompanied songs are the best things on this album--but unfortunately Prestige interspersed them with the band tracks, which means the mood keeps getting broken. The one significant pleasure of the jazz tracks is Bob Dylan's early absurdity, "If I Had to Do It All Over Again, I'd Do It All Over You." As for the solo tracks, all are good and a few are among his finest work from this period: "St. Louis Tickle" was a groundbreaking arrangement of a classic rag for solo guitar and remains one of  the great fingerstyle instrumentals, "Kansas City Blues" is one of his most spare and distinctive accompaniments, and "Green Rocky Road" was probably Dave's all-time favorite song to perform, always remaining a staple of his repertoire. Given the modern era of downloads, I would pull those tracks rather than the whole album. (This album was reissued as the first half of the CD Two Sides of Dave Van Ronk, combined with some material rerecorded in the 1980s.)

the great fingerstyle instrumentals, "Kansas City Blues" is one of his most spare and distinctive accompaniments, and "Green Rocky Road" was probably Dave's all-time favorite song to perform, always remaining a staple of his repertoire. Given the modern era of downloads, I would pull those tracks rather than the whole album. (This album was reissued as the first half of the CD Two Sides of Dave Van Ronk, combined with some material rerecorded in the 1980s.)

Inside Dave Van Ronk (Prestige, 1964, now half of the CD titled Inside Dave Van Ronk, along with the Folksinger album)

Inside Dave Van Ronk (Prestige, 1964, now half of the CD titled Inside Dave Van Ronk, along with the Folksinger album)

Dave did this album because he owed Prestige one more and he didn't want to use his prime stage material: "So I pulled together a bunch of old ballads and a couple of music hall songs I had learned from my grandmother, material that I sang for my own amusement or sitting around with friends but that I rarely performed publicly, and I walked into the studio with an autoharp, a dulcimer, a banjo, a twelve-string guitar -- if I’d had marimbas, I would have played marimbas. They called the album Inside Dave Van Ronk, and I was actually pretty happy with it." Very much a mixed bag, but "Kentucky Moonshiner" is beautiful, "Brian O'Lynne" is a rollicking stage-Irish music hall number that is a lot of fun, and "I Buyed Me a Little Dog" is a tender, lovely performance of a weirdly surrealist lyric that probably reaches back to old English mummers' plays.

Ragtime Jug Stompers (Mercury, 1964)

Ragtime Jug Stompers (Mercury, 1964)

This was one of Dave's personal favorites, though the group only existed for a few months. He recalled, "We did not play much of the typical jug band repertoire, we were more of a string ragtime outfit with trad jazz overtones... We rehearsed a hell of a lot, we took it damn seriously, and we put together some intricate arrangements of classic rags, which we played very carefully and note for note, but the rest of our repertoire was blues and jazz." "Everybody Loves My Baby," "Sister Kate," and "You're a Viper" are much better examples of Dave's approach to good-time jazz material than the Red Onion LP, and the latter has some flamboyant guitar from Danny Kalb as well as one of Dave's most dreadful puns in the intro. The idea was to capitalize on the success of Jim Kweskin's Jug Band in Cambridge, but Dave's group was very different and never cohered like the Kweskin crew. That said, the rags are terrific and represent a high point of his arranging--perhaps less distinctive than his solo guitar rags, but more virtuosic, with Kalb, Barry Kornfeld, and Artie Rose playing lead on "St. Louis Tickle," "Temptation Rag," and "Georgia Camp Meeting. (That trio also did an offshoot LP as The Folkstringers.) Overall this was a side-trip from the mainstream of Dave's oeuvre, but remains well worth hearing.

Just Dave Van Ronk (Mercury, 1964)

Just Dave Van Ronk (Mercury, 1964)

This is the next major Van Ronk solo LP after Folksinger, though it is far less well-known. The three LPs he had made in the previous year and a half were all experiments or side projects, and this was the next look at his evolving performance repertoire. "Candy Man" and "God Bless the Child" remained staples of his repertoire; "Bad Dream Blues" was his first significant composition (he did a better version of it on Elektra's Blues Project LP, but good luck finding that), and his rewrite of the Frankie and Johnny story as "Frankie's Blues" is also fine. There is also a soulful version of "Wanderin'," which I regularly used to request at his shows and which always blew me away. Without going through the rest of the selections, suffice it to say that this is not the place to start but it is essential for any Van Ronk fan.

No Dirty Names (Verve/Forecast, 1966)

No Dirty Names (Verve/Forecast, 1966)

For me, this is another canonical LP, probably the one I listened to most after Folksinger. Dave disagreed, but as far as I could tell that was because he was cranky about the recording sessions themselves--he kept playing most of these songs for decades and they include a lot of his greatest performances. It has some other players with him, including Dave Woods on guitar, but the basic backing is Dave's own guitar, including his beautiful reworking of Leroy Carr's piano chart for "Midnight Hour Blues." The song selection was more varied than ever, including "One of these Days" from Mose Allison, a setting of W.B. Yeats's "Song of Wandering Aengus," an obscure and unusually understated Dylan song, "The Old Man," and a fine reading of Brecht and Weill's "Alabama Song." Also the first example of Dave's own writing in what would become known as "singer-songwriter" style, a tribute to MacDougal Street called "Zen Koans Gonna Rise Again," and his greatest scat break on record, in "One Meatball." The other stuff is good too--there's not a track I would skip, and I keep coming back to this disc with pleasure.

Live at Sir George Williams University, recorded in 1967, has solo versions of half-dozen of the songs on No Dirty Names, and if I compared them I might well prefer some of these to the original LP tracks. It also has Dave's best reading of Brecht/Weill's "Mack the Knife"--a pretty definitive reading, in fact, putting the various pop versions to shame. And one of his seriocomic reworkings of "Cocaine," complete with connecting interludes of understated scat singing, which may be my favorite of his many versions of this classic. All in all, this is the one live release that shows Dave at his mid-1960s peak, and should probably be added to the "essentials" list.

Live at Sir George Williams University, recorded in 1967, has solo versions of half-dozen of the songs on No Dirty Names, and if I compared them I might well prefer some of these to the original LP tracks. It also has Dave's best reading of Brecht/Weill's "Mack the Knife"--a pretty definitive reading, in fact, putting the various pop versions to shame. And one of his seriocomic reworkings of "Cocaine," complete with connecting interludes of understated scat singing, which may be my favorite of his many versions of this classic. All in all, this is the one live release that shows Dave at his mid-1960s peak, and should probably be added to the "essentials" list.

Dave Van Ronk and the Hudson Dusters (Mercury, 1968)

Dave Van Ronk and the Hudson Dusters (Mercury, 1968)

Dave favored this over most of his other 1960s albums, which just shows you can't always trust an artist's opinion of his own work. It was his attempt to jump on the rock bandwagon, and he loved the chance to pull a band together and explore some avant-garde musical directions--in his words, "I felt like a kid with a new locomotive and a basement full of track, and that remains one of the few albums of mine that I enjoy listening to." I understand how much fun he had, but the result is mixed at best. His favorite track was "Dink's Song," which he called "technically the best piece of singing I have ever done on record," thanks to a flu that somehow added an octave to his falsetto range, and it is an impressive vocal, but I don't know anyone else who thinks it was his best. There are some other nice tracks--I particularly like his growling remake of "Alley Oop," which leaves the Hollywood Argyles' original in the shade and includes a bit of his W.C. Fields imitation, and his own "Head Inspector" is an amusing period piece, as is Peter Stampfel's "Romping through the Swamp," a whacked out new lyric to a Cajun accordion tune. In terms of his later evolution, the most interesting tracks are his first two versions of Joni Mitchell songs. "Chelsea Morning" is nothing special, but "Clouds" (his title for "Both Sides Now," which she used for her own LP) was the closest he came to a hit. His vocal is gorgeous, but the arrangement doesn't do it justice and anyone who wants to hear him sing this should check out the version on The Mayor of MacDougal Street. There is also a reading of "Cocaine" with a bunch of funny interpolations indicating how sick he had become of the song many people were treating as his masterpiece (again, there's a better version of this comical reworking, on Live at George Williams College). The rest of the selections are originals by guitarist Dave Woods, all quickly forgotten.

Van Ronk (Polydor, 1971)

Van Ronk (Polydor, 1971)

Dave and I both had a love/hate relationship with this album, because it had some of his greatest material but the arrangements keep undercutting or overwhelming his vocals. His take was, "they gave me impressive recording budgets, and we worked out some pretty interesting arrangements, with strings and horns and what-all. I enjoyed that, at times, and it gave me a chance to do some material that I would not have otherwise done, though I also was coaxed into doing some arrangements that even at the time seemed overblown and buried the material." In this period he had fully committed himself to the new styles being created by friends like Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen, which he thought of as a new kind of art or cabaret song and mixed with Brecht and Jacques Brel. His version of Mitchell's "Urge for Going" stays pretty close to his guitar chart, with nice strings, and is altogether a good example of what he could do with full orchestration (though he hated the drums), and "Legend of the Dead Soldier" is one of his most frighteningly powerful versions of a Brecht lyric. Peter Stampfel's "Random Canyon" is Dave at his most intentionally and ridiculously bombastic, and works just fine. "Fox's Minstrel Show" is a strange piece of material, but well suited to the big arrangement, and although Dave eventually decided that Brel's "Port of Amsterdam" was too drenched in nostalgie de la boue, he sings it well. Dave kept toying with the idea of rerecording the material he liked best from this album, but was held back by the fact that he never worked out his own ways of performing things like the Brel or Randy Newman's "I Think It's Going To Rain Today. All in all, this is a mixed bag, but well worth hearing after one knows his basic repertoire--I find it exciting to revisit it once and a while and wonder what he might have done if he'd had the chance to go on experimenting with these kinds of production values.

Songs for Ageing Children (Cadet, 1973)

Songs for Ageing Children (Cadet, 1973)

Another album with plenty of backing musicians, but more in keeping with Dave's personal aesthetic. Not all the tracks work, but some are terrific. His version of Joni Mitchell's "River" is beautiful, and his own "Song to Joni" shows how deeply he had immersed himself in her work--he thought she was the single most talented writer to come out of the 1960s folk scene, and she thought he was the only singer who did her songs better than she did them herself. "As You Make Your Bed" may be Dave's strongest Brecht/Weill performance, and he did his own translation of the lyric, which should become the standard. "Teddy Bear's Picnic" is the standard for this song, as far as I'm concerned--of all the songs he did on record that he never performed live, this is my favorite. Another personal favorite is his version of "My Little Grass Shack in Kealakekua, Hawaii," which is frankly kind of dreadful, but the way he comes in shouting over the vocal quartet at the end is one of my all-time highpoints of Ronkiana. And "Last Call" is one of his greatest compositions--I go back and forth about whether I like this version with Lou Killen's concertina better than the solo version on Going Back to Brooklyn. The weakest tracks are attempts to create new arrangements for his standard repertoire pieces, "Candy Man" and "Duncan and Brady." I wouldn't advise newcomers to start here, but it is an apt closer to the first period of Dave's career.

Sunday Street (Philo, 1976)

Sunday Street (Philo, 1976)

This one came out the year I spent studying with Dave, so I'm not impartial about it--but it's undoubtedly one of his greatest albums, maybe all the way up there with Folksinger. This was Dave's return to what he did best, singing with his guitar as the only accompaniment, and also his chance to show how much he had learned and grown in the dozen years since he had last recorded in this format. The title song is his best-known composition, a masterpiece of hip lyrics and inventive guitar within the basic 12-bar blues form. "Down South Blues" is an old Scrapper Blackwell song he had been working on for years and finally got the way he wanted it, and in later years he made this his standard set-opener. "Mamie's Blues" and "Jesus Met the Woman at the Well" show how much his singing had matured. "Maple Leaf Rag" and "The Pearls" show how he had continued to develop as a ragtime guitar arranger. "Would You Like to Swing on a Star" is one of his most charmingly silly performances of a song that was always an audience favorite. "That Song About the Midway" is another of his masterful readings of a Joni Mitchell composition. "That'll Never Happen No More" is a Blind Blake song he substantially rewrote and had been playing since the early 1960s, but had never recorded on a studio album. "Nobody Knows the Way I Feel this Morning" heralded a new style of arranging blues accompaniments, which he would expand on in later years, basing himself less on traditional blues guitar styles and more on the techniques he had developed for his ragtime arrangements. As I say, I'm not impartial about this one, but it's great.

Somebody Else, Not Me (Philo, 1980)

Somebody Else, Not Me (Philo, 1980)

When this came out, I was still completely under the spell of Sunday Street and didn't fully appreciate it. In retrospect, I think of the two albums as a set and am not entirely sure which I prefer. This has a more straightforward song selection, heavy on traditional blues, including two of Dave's greatest blues arrangements, Jelly Roll Morton's "Michigan Water Blues" and Brownie McGhee's "Sportin' Life." The only modern compositions are two tributes to folk father figures, Dylan's "Song to Woody" and Tom Paxton's "Did You Hear John Hurt." There is one classic ragtime instrumental, "The Entertainer," but the ragtime masterpiece is Dave's backing chart for Bert Williams's old comic monologue, "Somebody Else, Not Me." Typically, Dave did not mention in the notes that the third verse to this is his own composition--he often rewrote songs that he thought were too short or otherwise needed improving, and rarely mentioned that fact, and this verse is a terrific addition. The other songs show his continued and maturing devotion to older traditions: the a cappella "Go Down, Old Hannah" is something he rarely attempted onstage, and I wish he'd done more of this. And "Old Blue" was something I often asked him to perform live (and eventually recorded myself, because I couldn't get it out of my system).

When this came out, I was still completely under the spell of Sunday Street and didn't fully appreciate it. In retrospect, I think of the two albums as a set and am not entirely sure which I prefer. This has a more straightforward song selection, heavy on traditional blues, including two of Dave's greatest blues arrangements, Jelly Roll Morton's "Michigan Water Blues" and Brownie McGhee's "Sportin' Life." The only modern compositions are two tributes to folk father figures, Dylan's "Song to Woody" and Tom Paxton's "Did You Hear John Hurt." There is one classic ragtime instrumental, "The Entertainer," but the ragtime masterpiece is Dave's backing chart for Bert Williams's old comic monologue, "Somebody Else, Not Me." Typically, Dave did not mention in the notes that the third verse to this is his own composition--he often rewrote songs that he thought were too short or otherwise needed improving, and rarely mentioned that fact, and this verse is a terrific addition. The other songs show his continued and maturing devotion to older traditions: the a cappella "Go Down, Old Hannah" is something he rarely attempted onstage, and I wish he'd done more of this. And "Old Blue" was something I often asked him to perform live (and eventually recorded myself, because I couldn't get it out of my system).

Going Back to Brooklyn (Reckless, 1985)

Going Back to Brooklyn (Reckless, 1985)

This album belongs alongside the two Philo releases, since he originally recorded most of it for Philo, shortly after Somebody Else. It remained on the shelf for a while, though, and only came out in the mid-1980s--on a label I briefly had with another musician, Bill Morrissey (which suggests how impartial I am about it). The point of this album was to show what Dave could do as a songwriter, and it included some songs he had done on previous albums as well as some new material and a couple of older oddities he had never bothered to commit to vinyl. The new material was undoubtedly strongest: "Another Time and Place," which he wrote for his then lady, Joanne Grace, is the prettiest song he ever wrote and should have been covered by someone who would have made him a million dollars. "Losers"--which he considered as an album title, before thinking better of that--is his funniest lyric, though I guess some New Yorkers would give that honor to "Garden State Stomp," a ragtime instrumental backing a lyric made up entirely of names of towns in New Jersey. "Luang Prabang" was his brutal attempt at an un-wimpy anti-war song. "Honey Hair" is a Joni Mitchell-influenced lyric he wrote to the tune of a Bulgarian folk song, which he recorded for Polydor, but in the wrong time signature because the studio guys couldn't handle the Balkan 5/4 (or whatever it is). "Antelope Rag" was Dave's one attempt to write a full classic ragtime composition, on the theory that it was time to create something specifically for guitar rather than adapting piano rags, and it shows just how thoroughly he had mastered the style. In retrospect, I shouldn't have encouraged him to record "The Whores of San Pedro," a filthy throwaway he made up during his time in the Merchant Marine--but what the hell. The point of this record was to get his songs recorded by some other artists and pay the rent, and it didn't work--but it deserved to reach a lot more people than it did, and has a lot of great material that should be better known. Dave may have been greater as a singer and guitarist than as a songwriter, but he was a hell of a songwriter. He didn't push that aspect of his artistry very hard, because it irritated him that so many people were only singing their own songs. He didn't think it made sense to sing his own compositions unless they could stand up to the rest of his repertoire, which meant he often highlighted other songs rather than his own, but also that when he chose to highlight one of his, it was first-rate.

Let No One Deceive You: Songs of Bertolt Brecht (Aural Tradition/Flying Fish, 1990)

Let No One Deceive You: Songs of Bertolt Brecht (Aural Tradition/Flying Fish, 1990)

A duet album with the British singer Frankie Armstrong (though only one track is an actual duet), this finally gave Dave a chance to record all his favorite Brecht material. I'm perhaps prejudiced, since I arranged and played the guitar part for "A Man's a Man," or perhaps not, since I think it's Dave's least interesting song on the CD. The exceptional masterpiece here is his a cappella performance of "Let No One Deceive You," one of the less familiar songs, which I often requested and he only occasionally performed. It is one of Brecht's great lyrics, and Dave captured all of its depth and complexity. Other than those two songs and a duet with Armstrong on the "Tango Ballad" from Three-Penny Opera, Dave had recorded all of his contributions elsewhere, and in my opinion the other versions are stronger. He was a great Brecht interpreter, and those versions are all well worth hearing, especially "As You Make Your Bed" on Songs for Ageing Children.

Peter and the Wolf (Alacazam, 1990)

Peter and the Wolf (Alacazam, 1990)

I love the idea of Dave as Uncle Moose doing a jug band version of Prokofiev's Peter and the Wolf, but never really went wild for the finished object. However, the other tracks are a nice selection of Dave's more kid-focused repertoire, with tasteful arrangements by clarinetist Billy Novick, who also plays beautifully on the Bahamian "Foolish Frog." The great reason to check this out, though, is an odd little composition that became Dave's theme song in later years, "I'm Proud to be a Moose." It is one of his most charming performances, and he often ended sets with it.

Sweet & Lowdown (Justin Time, 2001)

Sweet & Lowdown (Justin Time, 2001)

Dave made a first swing album, Hummin' to Myself, in 1990, in part to prove that he could do it and in part because he had a dream of spending his later years working places like the Carlyle in New York, singing standards with a good piano player. That album did prove he could sing standards, but was a bit stiff, and I am forever glad that he got a chance to do another and really have some fun with the style. He had a great band, led by Keith Ingham on piano, with a covey of first-call New York players including Vince Giordano and Scott Robinson, and he selected a quirky variety of songs, from Bob Hope's theme, "Thanks for the Memories" to "Zoot Suit" and "Puttin' on the Ritz," for which he wrote some new lyrics. I enjoy the whole album, but am particularly fond of "I'd Rather Charleston," which includes the one recorded appearance of Dave's wife Andrea, doing a sort of Betty Boop character while he plays her wise and clueless Uncle Moose.

...and the tin pan bended and the story ended... (Smithsonian/Folkways, 2004)

...and the tin pan bended and the story ended... (Smithsonian/Folkways, 2004)

This was Dave's last concert, and is a terrific example of his later performance style, a blend of music and commentary, mixing opinions, memories, and anecdotes about the musicians he had known and admired through the years. It was also a chance for Dave to record a bunch of arrangements he had worked out over the previous half-dozen years and been recording for a new album that he realized he might never have a chance to finish. These include his new arrangement of "Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out," for which he wrote a tender and appropriate verse; the pop-blues "Jelly Jelly"; Josh White's "Sometime"; and Dylan's "Buckets of Rain." The new arrangements are great, the old ones are too, the stories are funny and illuminating... The man was a pro, and the fact that he did this set knowing it might be his last and made it so exuberantly alive is a testament to how much he cared about the music and loved doing it. This is a really astonishing record, and I recommend it very highly--with the caveat that it really needs to be heard in its entirety, with full attention. It is a one-man theatrical presentation, a personal summing-up of a lifetime's work, and it is funny and touching and wise--an appropriate last testament for a great artist.

The Mayor of MacDougal Street (Rootstock, 2005)

The Mayor of MacDougal Street (Rootstock, 2005)

I put this together when the book came out, culling Dave's collection of live recordings and ephemera for material that would surprise and interest old fans, from his first recordings in 1957 through the 1960s. As such, it is not the place to start exploring his work, but is a good supplement to his studio recordings from that period. For anyone compiling their own "best of" in downloads, the masterpiece here is his version of Joni Mitchell's "Both Sides Now"--his studio version was cluttered with additional instrumentation and this is the one recorded version that fully captures the rough delicacy he brought to her work. Other highlights are a couple of a cappella ballads; the best version of one of his early standards, "Willie the Weeper"; a nice version of Jelly Roll Morton's "Buddy Bolden's blues that shows the early stages of his "St. Louis Tickle" guitar arrangement; the one released sample from his collection of satirical songs of the American left, "Way Down in Lubyanka Prison"; and his W.C. Fields routine. Also a unique composition from his Mitchell-influenced singer-songwriter period, "In Conditional Support of Beauty."

Down in Washington Square (Smithsonian/Folkways, 2013)

Down in Washington Square (Smithsonian/Folkways, 2013)

This is mainly drawn from Dave's Folkways LPs, which I briefly discuss above, supplemented with live recordings from the late 1950s and early 1960s, some of which are pretty interesting, a mix of some later and relatively minor material from various sources, and his final five studio recordings, from an album he never finished. Several of those last songs are also on and the Tin Can Bended, and to my surprise the live versions are generally better, the exception being "Ace In the Hole," a trad jazz standard that he provided with some new lyrics and a brilliantly intricate guitar arrangement that is best displayed here. Of the early material not previously heard, his version of "Mean Old Frisco" is fine, as is an early original blues, "Had My Money," based on Robert Johnson's "If I Had Possession over Judgment Day."

Dave made a few other albums in the 1980s and 1990s, all quickie productions done in Europe or elsewhere and designed as samplers of his repertoire. They are not bad, and from...Another Time and Place even garnered him a Grammy nomination,

Dave made a few other albums in the 1980s and 1990s, all quickie productions done in Europe or elsewhere and designed as samplers of his repertoire. They are not bad, and from...Another Time and Place even garnered him a Grammy nomination,  but they include no new material, and all the old material had been recorded better on other albums--if any listeners disagree and want to propose examples I should highlight, let me know, but my overall judgment is that Dave worked very hard on his studio albums, assiduously rehearsing them beforehand and taking time to get the best possible take in the studio, and with the exception of his final live concert and a few songs that were messed up in the studio by over-production, the canonical LPs tend to have the canonical takes.

but they include no new material, and all the old material had been recorded better on other albums--if any listeners disagree and want to propose examples I should highlight, let me know, but my overall judgment is that Dave worked very hard on his studio albums, assiduously rehearsing them beforehand and taking time to get the best possible take in the studio, and with the exception of his final live concert and a few songs that were messed up in the studio by over-production, the canonical LPs tend to have the canonical takes.