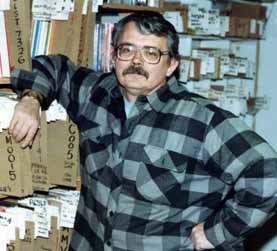

John Storm Roberts Rides the 'World Music' Wave

[The Blues] [Other writing] [African Guitar CDs] [Blues CDs] [My CD and album projects] [Joseph Spence guitar DVD] [Elijah Wald bio]

By Elijah Wald

Originally published in the Boston Globe, February 22, 1989

TIVOLI. N.Y. - “I’ve come to the conclusion that the reason I haven’t won the lottery is that God knows I will buy an ophicleide and bother the neighbors.” says John Storm Roberts. “I don’t know If you’ve ever seen an ophicleide. It’s a most peculiar instrument from the Victorian era. It’s kind of like a saxophone, except that it uses a trombone mouthpiece.”

Roberts, a charming man with a wry English accent, is a major figure in the current “world music” upsurge. He has written two widely-cited books, Black Music of Two Worlds, on the evolution of African music and African-influenced music of the Americas and The Latin Tinge, on the Latin influence in the music of the United States. His record and mail-order company, Original Music, carries music from six continents.

Roberts, a charming man with a wry English accent, is a major figure in the current “world music” upsurge. He has written two widely-cited books, Black Music of Two Worlds, on the evolution of African music and African-influenced music of the Americas and The Latin Tinge, on the Latin influence in the music of the United States. His record and mail-order company, Original Music, carries music from six continents.

Roberts lives in the country near Tivoli, a hamlet two hours north of New York City. He and his wife, Anne Needham, run Original Music out of an old red barn behind their house, with the help of one full-time employee, Carl Hoyt. Though best-known for superb African records, they carry “everything from country blues to Korean classical music.”

Roberts prides himself on his eclecticism. For example: “We discovered, in Chinatown, some tapes which I can only describe as Vietnamese techno-tango. We got a few of them as a kind of a giggle, and to be able to claim that we carried weird stuff that nobody else did. The amazing thing is that we can’t keep it in stock.”

Sitting back in his armchair, a trombone visible in the kitchen and a duck wandering around outside the window. Roberts explains that his musical tastes were formed during his childhood in London. “It’s all my parents’ fault. They bought me one of those plug-into-a-radio, electric-but-78-only, machines when I was 13, with three records. They were on the order of ‘Sheep May Safely Graze.’ by good old J.S.B.; La Niña de las Peines, the flamenco singer; and Bessie Smith.

“My father had been listening to black music in the ’20s. He had a rich friend in Cambridge, who imported the whole OKeh catalog. He had a sensational collection, including very bad stuff that’s long forgotten, of course. But they were listening to Peg Leg Howell in the Cambridge of the ’20s.

“My parents lived in Chelsea in the ’30s and flamenco was big. They also knew calypso. Then my father used to go every six months to Lisbon on business and would bring me back Amalia Rodrigues and Luis Gonzaga, the Brazilian accordion player.”

Soon Roberts was buying for himself. “They used to have sixpenny trays outside record stores, and I bought an Umm Kulthum record. She’s kind of the Egyptian Bessie Smith, only much more so. I didn’t know what the record was. I knew it was Egyptian, because it said Cairophone at the top, and it said Umm Kulthum at the bottom, but otherwise it said squiggle, squiggle, squiggle. It was only two years later that I met a couple of Iraqis who told me something about her. So I was just buying all sorts of stuff. If I couldn’t even figure out what the alphabet was. I was in seventh heaven.”

Roberts began working as a journalist in London and started writing about African music when he went to Kenya in 1963. “I was writing for the East African Standard, and I discovered that there was this agreeable guitar-based music on the Swahili-language radio and nobody could tell me anything about it. I suggested that I do something on this pop music. So I went out and interviewed musicians and got them to write down their lyrics on the backs of cigarette packets and did this page-one-of-the-cultural-section article.”

He went on to do regular record reviews and articles on the local music. Returning to London after three years, he wrote about African music and worked for the BBC Swahili section, a Swahili language shortwave from London for East Africa. Then, in 1970, he came to the United States.

“I came over to be managing editor of Africa Report. An American academic whom I’d known in Kenya had become editor and he needed someone to run the bloody magazine; I’d started getting back into Afro-American music, so it seemed logical to come here. I came over with my first wife and two kids and settled in Brooklyn, became editor of Africa Report and got involved in a film with Ossle Davis of a story I had written. The film was called Countdown at Kusini.’ It was one of the turkeys of l976.”

After leaving Africa Report, Roberts spent five years free-lancing as among other things, High Fidelity’s R&B man and the “hyphenated-Latin” expert for the Village Voice. After two more magazine jobs, he started Original Music in 1980. He says it was a logical progression: “The real reason anybody is a journalist is that they wish to educate, instruct, but, much more majorly, share enthusiasms. You discover that something is wonderful, and you want to share it, spread it around.”

Original Music started with a one-page catalog featuring Roberts’ two books and Africa Dances, a record surveying the African pop scene, which he had compiled in the early ’70s. “Africa Dances was done because everybody thought African music was drums.”

Roberts wanted to show the breadth of African pop. “Africa has more types of instruments than any other continent. One of the things people don’t realize about drums in Africa is that there is an ecological basis. There are large drums where there are large trees. Certain tribes, if they live on grasslands, have essentially no musical instruments except shakers and the occasional gourd. Stringed instruments are very widespread.”

Roberts says African pop is essentially guitar-based: “Cuban music started becoming enormously popular in Africa in the ’30s. What created Congolese, which is much the most influential of the styles, was the mimicking of Cuban records, playing riffs which the Cubans played on trumpets or fiddles on guitar. That and American country music. Enormously popular in his time was Jimmy Rodgers and then, in the ’60s, Jim Reeves. One of these weird people who do statistics discovered that, outside the States, Jim Reeves’s greatest popularity in, I think, 1965, was in Norway and the second greatest was in Kenya.”

In the last few years, the amount of international music available in the United States has skyrocketed, first with the popularity of such artists as King Sunny Ade and collaborations such as Paul Simon’s Graceland and, more recently, with such exotic ethnic fusions as Ofra Haza’s Yemeni Jewish techno-pop.

Though certain obscure musics are becoming more accessible, Roberts sees the fusions as a mixed blessing. “What upsets me is that, when you get what might be an interesting experiment as the only thing available, where the original musics are not available, that’s just the wrong way round. It makes the whole movement a kind of ongoing novelty carnival, the musical equivalent of ’60s culture tripping, with a bit of Hinduism and a bit of acid and let’s go to Katmandu with mummy’s credit card.

“I’m quite sure that what changes music and develops new music is an almost unconscious mass movement. It wasn’t that a guitarist in the Congo decided to mess with Cuban music. It was that the Congolese developed a passion for Cuban music and started trying to do it and couldn’t do it very well, luckily, and developed their own style.”

The history of that development Is traced on The Kinshasa Sound, a chronological anthology that meets Roberts’ criteria: “genuine music which also sounds real nice.” Other standout records include The Nairobi Sound, and recent African Acoustic anthologies, two LPs and a compact disc.

Original Music’s catalog, including supplements, now has well over 100 pages, listing records, cassettes, CDs, books and videos. The listings include Roberts’ descriptions of each offering, and he also offers “core” catalogs, outlining surveys of specific musical areas.

As for the ophicleide and the helicon, which he says is “like a sousaphone, but more elegant,” Roberts plays music himself, though only as a hobby. “One of my current themes is, I have lung problems and I’m working on trying to persuade my doctor that what I need for pulmonary exercise is a tuba. I have a passion for deep brass, and I like the idea of buying a tuba on Blue Cross.”