Celebrating one of the main railroad lines out of the South, this is another song I got from Larry Johnson, who presumably got it from Jim Jackson. I don’t recall when I started playing it with this arrangement, but by the late 1980s it was my regular set-closer.

I also played it pretty regularly during my 1987-88 winter residency in Sevilla, Spain — unquestionably my hardest-working period as a blues player. I was in Sevilla with some friends from Antwerp, Vera Singelyn, her toddler son Liam, and a Dutch girl named Tim, and lucked into regular work thanks to a local harmonica player named Juan Guerrero.

I also played it pretty regularly during my 1987-88 winter residency in Sevilla, Spain — unquestionably my hardest-working period as a blues player. I was in Sevilla with some friends from Antwerp, Vera Singelyn, her toddler son Liam, and a Dutch girl named Tim, and lucked into regular work thanks to a local harmonica player named Juan Guerrero.

I met Juan at a bar gig by the Caldonia Blues Band, a local outfit that played electric Chicago style. I’d brought my guitar, hoping to connect to the local scene, and Juan got excited because he was a Sonny Terry fan but had been stuck playing amplified because no one in Andalucia played acoustic blues. We jammed during the break, he asked how long I could stay in town, I said I could be there all winter, and he asked how many nights a week I wanted to work. I said six, figuring there was no way that would happen, and he said, “OK, check back with me in two weeks.”

Two weeks later I checked back with him and he’d found a bass player, Juan Arias, and booked us as either a duo or trio six nights a week for the next three months. We played every Monday in one bar, every  Tuesday in another, and so on. He’d also named us the Mississippi Sheiks, which felt weird to me since I’d never been in Mississippi and that name was already taken by one of the great groups of the 1920s… but Juan liked it, and he was the boss.

Tuesday in another, and so on. He’d also named us the Mississippi Sheiks, which felt weird to me since I’d never been in Mississippi and that name was already taken by one of the great groups of the 1920s… but Juan liked it, and he was the boss.

The gigs were all full-night residencies, typically three one-hour sets with half hour breaks between, and sometimes a fourth set if the bar was still jumping. For the smaller places we worked acoustic, for the larger ones or when we had the bass we used a couple of small amps. It was great practice, and forced me to get back into blues, which I’d been moving away from over the previous few years as my tastes expanded. It also led to some interesting connections with local flamenco players, — Sevilla was a center of flamenco-blues fusion, thanks to a pair of Gypsy brothers who’d formed a band in  the 1970s called La Pata Negra, mixing flamenco with Jeff Beck-style electric leads. (For a taste, check out their “Blues de la frontera.”) So I worked out a trade with a flamenco guitarist, during which he learned the basics of American fingerstyle blues and I learned I didn’t have the chops to play flamenco.

the 1970s called La Pata Negra, mixing flamenco with Jeff Beck-style electric leads. (For a taste, check out their “Blues de la frontera.”) So I worked out a trade with a flamenco guitarist, during which he learned the basics of American fingerstyle blues and I learned I didn’t have the chops to play flamenco.

I’ll continue the story of that winter in the next post, but the longterm result was that fifteen years later I was back in town and dropped by La Carboneria, there was an acoustic blues duo onstage, and the guitarist got all excited because he had been inspired to learn blues as a kid by hearing me with the Sheiks.

As for the Seaboard railroad lines, they were part of a network that reached down to Florida, over to New Orleans, and up to New York. In The Warmth of Other Suns, Isabel Wilkerson writes about the Seaboard as one of the main engines of the Great Migration, which adds another dimension to the song.

As for the Seaboard railroad lines, they were part of a network that reached down to Florida, over to New Orleans, and up to New York. In The Warmth of Other Suns, Isabel Wilkerson writes about the Seaboard as one of the main engines of the Great Migration, which adds another dimension to the song.

In the mid 1980s Vera Singelyn was running a place in Antwerp that provided cheap rooms and dinners for street people and buskers, and she had a four-month-old son, Liam. He was a pretty tranquil kid but one evening he started crying just as she was trying to dish out food for a couple of dozen people, so I picked him up and bounced him, and when he kept crying I asked Vera if I could carry him around the block…

In the mid 1980s Vera Singelyn was running a place in Antwerp that provided cheap rooms and dinners for street people and buskers, and she had a four-month-old son, Liam. He was a pretty tranquil kid but one evening he started crying just as she was trying to dish out food for a couple of dozen people, so I picked him up and bounced him, and when he kept crying I asked Vera if I could carry him around the block… That was also where Liam made his debut as a clown — by then, he knew that when Vera put on make-up she would be going out, so he would start screaming, and that afternoon we dealt with the situation by making him up as well and bringing him along. I waited till Vera had a crowd around her, then released him, and he ran over to her hat, picked it up, carried it around the circle, and made a small fortune in coins… then went back to the center of the circle, dumped the coins on the ground, picked up two handfuls, and started distributing them to the other children in the crowd.

That was also where Liam made his debut as a clown — by then, he knew that when Vera put on make-up she would be going out, so he would start screaming, and that afternoon we dealt with the situation by making him up as well and bringing him along. I waited till Vera had a crowd around her, then released him, and he ran over to her hat, picked it up, carried it around the circle, and made a small fortune in coins… then went back to the center of the circle, dumped the coins on the ground, picked up two handfuls, and started distributing them to the other children in the crowd. at the Caffe Lena in Saratoga, and he stayed with me whenever he was in Cambridge, and I stayed with him in Spokane and later in Grass Valley. He was genuinely a gentleman and a scholar, and one of his fields of scholarship was the old west. This song was inspired by the name of one of the main cattle trails out of Texas, pioneered by Charlie Goodnight and Oliver Loving in the 1860s, which went up through New Mexico to Colorado and eventually Wyoming.

at the Caffe Lena in Saratoga, and he stayed with me whenever he was in Cambridge, and I stayed with him in Spokane and later in Grass Valley. He was genuinely a gentleman and a scholar, and one of his fields of scholarship was the old west. This song was inspired by the name of one of the main cattle trails out of Texas, pioneered by Charlie Goodnight and Oliver Loving in the 1860s, which went up through New Mexico to Colorado and eventually Wyoming. ago, I had the pleasure of watching a salesman marketing aceite de vibora.

ago, I had the pleasure of watching a salesman marketing aceite de vibora. soup kitchen that was a dinner stop and occasional lodging for much of the itinerant musical population. I don’t remember how I first met Vera, but it was probably at Den Billekletser, because that was where a lot of us called home during the daytimes. It was a bar on the Hoogstraat, near the banks of cafes surrounding the Cathedral, and we would start drinking coffee there in the morning, graduate to beer around noon, and continue through the evening between sorties to play the cafes, restaurants, and bars. Some people got their mail delivered there, and for ten years or so I would go there first whenever I hit town and find out who else was around and where they were living.

soup kitchen that was a dinner stop and occasional lodging for much of the itinerant musical population. I don’t remember how I first met Vera, but it was probably at Den Billekletser, because that was where a lot of us called home during the daytimes. It was a bar on the Hoogstraat, near the banks of cafes surrounding the Cathedral, and we would start drinking coffee there in the morning, graduate to beer around noon, and continue through the evening between sorties to play the cafes, restaurants, and bars. Some people got their mail delivered there, and for ten years or so I would go there first whenever I hit town and find out who else was around and where they were living. It’s also possible that I met Vera at the Musik Doos, which was in a couple of different locations over the years and had a stage and microphones for whoever wanted to play a set and pass the hat. Etienne, the owner, was always good to me and I made a lot of friends there. Or maybe someone just brought me over to the place Vera was running to have some dinner.

It’s also possible that I met Vera at the Musik Doos, which was in a couple of different locations over the years and had a stage and microphones for whoever wanted to play a set and pass the hat. Etienne, the owner, was always good to me and I made a lot of friends there. Or maybe someone just brought me over to the place Vera was running to have some dinner. waifs and wastrels, and shortly she was letting me live in an apartment on the third floor of a house she had at Huikstraat 5, in the red light district. As I recall, Irish Tony and Jimmy were on the second floor, and Montana Bob and his daughter were on the fourth – or maybe Bob and his daughter had the other side of the third and

waifs and wastrels, and shortly she was letting me live in an apartment on the third floor of a house she had at Huikstraat 5, in the red light district. As I recall, Irish Tony and Jimmy were on the second floor, and Montana Bob and his daughter were on the fourth – or maybe Bob and his daughter had the other side of the third and  terraces in the daytime, and then Nick and I would get together and do the nice restaurants. We’d typically warm up by playing a standard in all twelve keys, and “Some of These Days” was one of our favorites, along with “

terraces in the daytime, and then Nick and I would get together and do the nice restaurants. We’d typically warm up by playing a standard in all twelve keys, and “Some of These Days” was one of our favorites, along with “ Dave Van Ronk’s version on his second swing CD, Sweet and Lowdown. As was his way, Dave wrote a great new introductory verse, and that got me singing it again, usually with my wife Sandrine on clarinet. Now I need to get back to Antwerp and try it again with Nick, whom I haven’t played with in almost thirty years — but see

Dave Van Ronk’s version on his second swing CD, Sweet and Lowdown. As was his way, Dave wrote a great new introductory verse, and that got me singing it again, usually with my wife Sandrine on clarinet. Now I need to get back to Antwerp and try it again with Nick, whom I haven’t played with in almost thirty years — but see  rarer on the busking scene. So I hit Paris, dropped in at

rarer on the busking scene. So I hit Paris, dropped in at  didn’t allow buskers. We’d go in and ask if we could play, and they’d say no, and we’d make a deal: we’d do one song, and if they didn’t want to hear another we’d leave without bothering the customers for money. So they’d grumble a bit, but give us a chance….

didn’t allow buskers. We’d go in and ask if we could play, and they’d say no, and we’d make a deal: we’d do one song, and if they didn’t want to hear another we’d leave without bothering the customers for money. So they’d grumble a bit, but give us a chance…. None of which connects directly to “Hello, Mary Lou,” except that I was working on my rock ‘n’ roll oldies repertoire and when I went out alone I played this as well as the Everly and Holly songs, and had a nicer guitar arrangement for it. I learned it off a record by Gene Pitney, which I picked up at a yard sale for next to nothing back in my teens — the hit version was by Ricky Nelson, but Pitney wrote it and I liked his version. It wasn’t as fancy as “Town without Pity” or “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” but more fun.

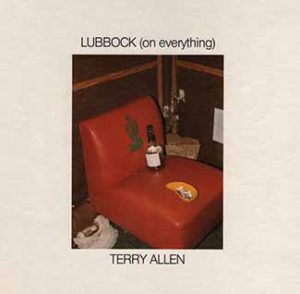

None of which connects directly to “Hello, Mary Lou,” except that I was working on my rock ‘n’ roll oldies repertoire and when I went out alone I played this as well as the Everly and Holly songs, and had a nicer guitar arrangement for it. I learned it off a record by Gene Pitney, which I picked up at a yard sale for next to nothing back in my teens — the hit version was by Ricky Nelson, but Pitney wrote it and I liked his version. It wasn’t as fancy as “Town without Pity” or “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” but more fun. first I thought of him as a quirky novelty writer and it took a couple of years before I immersed myself in that album. Thirty years later, it’s still a relatively little-known (though widely acknowledged) classic, and anyone who hasn’t heard it should just go out and buy a copy.

first I thought of him as a quirky novelty writer and it took a couple of years before I immersed myself in that album. Thirty years later, it’s still a relatively little-known (though widely acknowledged) classic, and anyone who hasn’t heard it should just go out and buy a copy. broadcasting over XERF in 1963 and in the early years concealed his identity, refusing interviews and photographs. Station promos showed a drawing of a hip wolf, or photographs of a hirsute face of uncertain ethnicity, eyes hidden behind dark shades. He broadcast from midnight till 4am, and could be

broadcasting over XERF in 1963 and in the early years concealed his identity, refusing interviews and photographs. Station promos showed a drawing of a hip wolf, or photographs of a hirsute face of uncertain ethnicity, eyes hidden behind dark shades. He broadcast from midnight till 4am, and could be  heard all over the Central and Western United States, and sometimes as far away as Europe. He played current hits, deep blues, grinding R&B, howled along with favorite records, sometimes called a lady friend live on the air, and was worshiped by millions of teenagers as a mysterious creature of the night.

heard all over the Central and Western United States, and sometimes as far away as Europe. He played current hits, deep blues, grinding R&B, howled along with favorite records, sometimes called a lady friend live on the air, and was worshiped by millions of teenagers as a mysterious creature of the night.

Ellen Steckert and Milt Okun, and for a long time I forgot about it because after I got into Woody Guthrie, Cisco Houston, and blues I tended to dismiss the songs on those albums as pseudo-folk juvenalia. I don’t remember when or why I revised my opinion — maybe I heard someone like Ian Tyson sing it — but anyway it became one of my favorites, especially when

Ellen Steckert and Milt Okun, and for a long time I forgot about it because after I got into Woody Guthrie, Cisco Houston, and blues I tended to dismiss the songs on those albums as pseudo-folk juvenalia. I don’t remember when or why I revised my opinion — maybe I heard someone like Ian Tyson sing it — but anyway it became one of my favorites, especially when  Another poster on that Mudcat thread cleared up a long-running geographical conundrum: the list of rivers in Randolph’s lyric includes the Natchez, which isn’t a river and isn’t in Texas, and Hinton, who was a Texan (born in Oklahoma, but raised in Crockett, TX), adapted that to Nacogdoches, which is in Texas but still isn’t a river (and doesn’t scan with the melody). However, the Mudcatter points out that there is a Neches River which flows through more than 400 miles of Texas. So the hired hand presumably sang “Neches” and Carlisle, being more familiar with Mississippi towns than Texas rivers, misheard it as “Natchez” — which doesn’t explain why Hinton, who grew up 30 miles from the Neches and would have had to cross it to reach Nacogdoches, didn’t make the correction.

Another poster on that Mudcat thread cleared up a long-running geographical conundrum: the list of rivers in Randolph’s lyric includes the Natchez, which isn’t a river and isn’t in Texas, and Hinton, who was a Texan (born in Oklahoma, but raised in Crockett, TX), adapted that to Nacogdoches, which is in Texas but still isn’t a river (and doesn’t scan with the melody). However, the Mudcatter points out that there is a Neches River which flows through more than 400 miles of Texas. So the hired hand presumably sang “Neches” and Carlisle, being more familiar with Mississippi towns than Texas rivers, misheard it as “Natchez” — which doesn’t explain why Hinton, who grew up 30 miles from the Neches and would have had to cross it to reach Nacogdoches, didn’t make the correction.

Nameless Coffeehouse that week or the next, I went down and heard him, and he was great. So I introduced him to Bill Morrissey and he became one of the gang, hanging out with me and Bill at Jeff McLaughlin’s house and various other places.

Nameless Coffeehouse that week or the next, I went down and heard him, and he was great. So I introduced him to Bill Morrissey and he became one of the gang, hanging out with me and Bill at Jeff McLaughlin’s house and various other places. long-running Saturday morning favorite, Hillbilly at Harvard. Our model was the Maddox Brothers and Rose, whose old radio broadcasts had recently been reissued by Arhoolie. We’d kid around and play songs, which meant working up new material every week, and we didn’t set the world on fire, but it was good practice.

long-running Saturday morning favorite, Hillbilly at Harvard. Our model was the Maddox Brothers and Rose, whose old radio broadcasts had recently been reissued by Arhoolie. We’d kid around and play songs, which meant working up new material every week, and we didn’t set the world on fire, but it was good practice. the Streetcorner Cowboys, with Robbie, Peter, me, Mark Earley on harmonica, and Matt Leavenworth showing up pretty often to sit in on fiddle. And then Peter moved to Austin, and the rest may be history, but not this history.

the Streetcorner Cowboys, with Robbie, Peter, me, Mark Earley on harmonica, and Matt Leavenworth showing up pretty often to sit in on fiddle. And then Peter moved to Austin, and the rest may be history, but not this history. The first verse, my oldest great-grandson, he made that himself, and from that each child would say a word and add to it. To tell the truth, I don’t know what got it started… but it must have been something said or something done. That’s practically how all my songs I pick up.

The first verse, my oldest great-grandson, he made that himself, and from that each child would say a word and add to it. To tell the truth, I don’t know what got it started… but it must have been something said or something done. That’s practically how all my songs I pick up.