Dave Van Ronk took pride in the fact that he recognized Bob Dylan’s talent early, back when a lot of people thought Bobby was  just a weird kid with too much nervous energy and a scratchy voice. Dave and his wife Terri Thal were major boosters for the kid, mentoring him, finding him jobs, and teaching him songs.

just a weird kid with too much nervous energy and a scratchy voice. Dave and his wife Terri Thal were major boosters for the kid, mentoring him, finding him jobs, and teaching him songs.

Dave also recorded a handful of Dylan songs: this one, a jazz band romp called “If I Had to Do It All Over Again (I’d Do It All Over You),” which I’ll get around to at some point, Dylan’s version of “He Was a Friend of Mine,” and, much later, a nice version of “Buckets of Rain.” He might have recorded more, but Dylan took off like a skyrocket and Dave had no interest in tagging along, so he stuck to older material for a while, then began singing the work of less-known newcomers like Neila Horne and Joni Mitchell, and even writing a few himself.

This was an exception, because Dylan hadn’t recorded it and it was so simple, and such a New York story. I’m pretty sure Dave was the first person to record it, on his No Dirty Names LP in 1966, but Dylan had written it about five years earlier during his first spate of songwriting. The melody was from a song called “The Young Man Who Wouldn’t Hoe Corn,” which I’m assuming Dylan, like everyone else, got from Pete Seeger, who recorded it in the mid-1950s on an album of frontier ballads.

The melody was from a song called “The Young Man Who Wouldn’t Hoe Corn,” which I’m assuming Dylan, like everyone else, got from Pete Seeger, who recorded it in the mid-1950s on an album of frontier ballads.

The original began:

I’ll sing you a song, it’s not very long,

About a young man who wouldn’t hoe corn.

Strange to say, I cannot tell,

This young man was always well.

Dylan took the pattern of that verse, changed the age of the man, and turned it into a stark parable of modern city life — a small, perfectly-observed vignette with a touch of brilliance that Dave often noted: “bully club,” rather than “billy club.”

I don’t want to go on, since the song itself is so concise, but… I’d add that Seeger was a very important source for Dylan, as for virtually everyone else in the folk revival, and some later scholars have tended to erase that influence by tracing Dylan songs to more obscure sources, in particular the Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music. The Smith anthology was an important source for a lot of people on that scene, but nowhere near as important as Seeger — I’d guess even the New Lost City Ramblers, if you’d locked them in a room and forced them to sing everything they knew, learned more songs from Pete than from any other single source. (If you want to know more of what I think about Dylan and Seeger, there’s plenty in Dylan Goes Electric!)

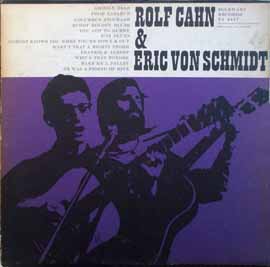

a duet LP with Rolf Cahn for the Folkways label that has not been treated well by history but was a seminal source for the folk-blues revivalists of the early 1960s. His source was a singer and guitarist named Smith Casey or Smith Cason, or possibly Smith Carson, who was recorded by John Lomax for the Library in 1939 at the Clemens State Prison Farm in Brazoria, Texas. In the LOC files it was titled “

a duet LP with Rolf Cahn for the Folkways label that has not been treated well by history but was a seminal source for the folk-blues revivalists of the early 1960s. His source was a singer and guitarist named Smith Casey or Smith Cason, or possibly Smith Carson, who was recorded by John Lomax for the Library in 1939 at the Clemens State Prison Farm in Brazoria, Texas. In the LOC files it was titled “ arrangement that turned a fairly generic blues lament into something great and enduring. Play his version back to back with Dylan’s, and the only difference is that Dylan’s is one of the many good but ultimately forgettable folk-blues songs he was singing in 1961-62, while Dave’s is a masterpiece.

arrangement that turned a fairly generic blues lament into something great and enduring. Play his version back to back with Dylan’s, and the only difference is that Dylan’s is one of the many good but ultimately forgettable folk-blues songs he was singing in 1961-62, while Dave’s is a masterpiece. had just followed my own inclinations. For example, I ended up with three Bo Carter albums, though I was never a huge fan of his music. I liked his playing and singing, and some of his songs, but he was the master of double-entendre novelty blues lyrics, which got tiresome after a while. All things being equal, I would have been more likely to gravitate toward Walter Davis or Roosevelt Sykes… but all things weren’t equal: he was a guitarist and they were pianists, and the reissue market was very guitar-centric.

had just followed my own inclinations. For example, I ended up with three Bo Carter albums, though I was never a huge fan of his music. I liked his playing and singing, and some of his songs, but he was the master of double-entendre novelty blues lyrics, which got tiresome after a while. All things being equal, I would have been more likely to gravitate toward Walter Davis or Roosevelt Sykes… but all things weren’t equal: he was a guitarist and they were pianists, and the reissue market was very guitar-centric. during

during  Following my generally archaeological inclinations, I didn’t get around to those until I’d laid in a stock of prewar stuff, and the first Blue Goose albums I bought were of Son House and an elderly black guitarist named Bill Williams, but eventually I got around to the label’s one young black player, Larry Johnson, and what still stands as the greatest ragtime blues album recorded in the modern era — or ever, since before the modern era there were no albums — Fast and Funky.

Following my generally archaeological inclinations, I didn’t get around to those until I’d laid in a stock of prewar stuff, and the first Blue Goose albums I bought were of Son House and an elderly black guitarist named Bill Williams, but eventually I got around to the label’s one young black player, Larry Johnson, and what still stands as the greatest ragtime blues album recorded in the modern era — or ever, since before the modern era there were no albums — Fast and Funky. Luke Jordan, who I’m pretty sure was their source as well as Johnson’s, and I’ve added some lyrics from Jordan, but it’s still Johnson’s voice I hear in my head when I think of it.

Luke Jordan, who I’m pretty sure was their source as well as Johnson’s, and I’ve added some lyrics from Jordan, but it’s still Johnson’s voice I hear in my head when I think of it. I’m gonna have your ma

I’m gonna have your ma Dave he steered me to his actual source: the Bahamian Blind Blake and his band from the Royal Victoria Hotel in Nassau. It is obviously related to a song recorded in the late 1920s by James “Stump” Johnson, Tampa Red, and others as “The Duck’s Yas Yas,” and that discographic primacy has led a lot of scholars to describe Blake’s song as a variant of Tampa Red’s. However, Blake’s lyric shares only the opening verse of the Red/Johnson version, and since his repertoire is full of turn-of-the-century minstrel survivals like “My Name is Morgan, But It Ain’t J.P.” and “Watermelon Spoilin’ on the Vine” (as well as the sole surviving version of a bloodthirsty minstrel masterpiece, “

Dave he steered me to his actual source: the Bahamian Blind Blake and his band from the Royal Victoria Hotel in Nassau. It is obviously related to a song recorded in the late 1920s by James “Stump” Johnson, Tampa Red, and others as “The Duck’s Yas Yas,” and that discographic primacy has led a lot of scholars to describe Blake’s song as a variant of Tampa Red’s. However, Blake’s lyric shares only the opening verse of the Red/Johnson version, and since his repertoire is full of turn-of-the-century minstrel survivals like “My Name is Morgan, But It Ain’t J.P.” and “Watermelon Spoilin’ on the Vine” (as well as the sole surviving version of a bloodthirsty minstrel masterpiece, “ fascinating. Much as I love a lot of old recordings, they are simply snapshots, frequently unrepresentative, from a huge pool of material people were singing in the early 20th century. Van Ronk still came up in a world where songs were often learned from other singers rather than from records, or from records he had only heard a couple of times and vaguely remembered. That was a disadvantage in a lot of ways, but also gave his generation a degree of freedom — they couldn’t remember how the “original” version went, exactly, so they had to do the best they could, and the result was sometimes better than the assiduous imitations that became more prevalent by my time, when we all had the old records on reissue LPs and could study them with infinite care.

fascinating. Much as I love a lot of old recordings, they are simply snapshots, frequently unrepresentative, from a huge pool of material people were singing in the early 20th century. Van Ronk still came up in a world where songs were often learned from other singers rather than from records, or from records he had only heard a couple of times and vaguely remembered. That was a disadvantage in a lot of ways, but also gave his generation a degree of freedom — they couldn’t remember how the “original” version went, exactly, so they had to do the best they could, and the result was sometimes better than the assiduous imitations that became more prevalent by my time, when we all had the old records on reissue LPs and could study them with infinite care. Dillinger verse, it’s an anachronism. My guess is that the verse itself is older and Dillinger replaced an earlier protagonist, but that’s just a guess — if other people want to credit Blake with writing a whole new set of verses and turning a relatively generic blues song into a cohesive comic creation, the evidence supports their guess at least as well as mine.)

Dillinger verse, it’s an anachronism. My guess is that the verse itself is older and Dillinger replaced an earlier protagonist, but that’s just a guess — if other people want to credit Blake with writing a whole new set of verses and turning a relatively generic blues song into a cohesive comic creation, the evidence supports their guess at least as well as mine.) sometimes didn’t, but pretty much all the players acknowledge his unique gifts: not only his superb guitar playing, rack harmonica work, and singing, but the way he always made the songs seem personal and quirky. He is an assiduous student of the old masters, spent the requisite years painstakingly hovering over scratchy 78s, figuring out how Blind Lemon Jefferson or Blind Willie McTell played a particular lick, but no matter how loyally he tried to capture their styles, his own individual touch and sensibility remain instantly recognizable.

sometimes didn’t, but pretty much all the players acknowledge his unique gifts: not only his superb guitar playing, rack harmonica work, and singing, but the way he always made the songs seem personal and quirky. He is an assiduous student of the old masters, spent the requisite years painstakingly hovering over scratchy 78s, figuring out how Blind Lemon Jefferson or Blind Willie McTell played a particular lick, but no matter how loyally he tried to capture their styles, his own individual touch and sensibility remain instantly recognizable. “Oh, yeah, that’s from the Bahamian Blind Blake. He’s got a lot of great material: that’s where I got ‘

“Oh, yeah, that’s from the Bahamian Blind Blake. He’s got a lot of great material: that’s where I got ‘ it dates from the first decade of the twentieth century, but so far no one has found sheet music or any other solid example before Blake recorded it circa 1950, and there’s no way to know how much it had changed over the years.

it dates from the first decade of the twentieth century, but so far no one has found sheet music or any other solid example before Blake recorded it circa 1950, and there’s no way to know how much it had changed over the years. “whetted butcher knife,” which made more sense — but a few years ago this became a hotly debated topic on a blues scholar list-serve and Yuval Taylor eventually solved the mystery: Wade & Butcher was the most popular brand of straight razor, the weapon of choice for minstrel-show comedy.

“whetted butcher knife,” which made more sense — but a few years ago this became a hotly debated topic on a blues scholar list-serve and Yuval Taylor eventually solved the mystery: Wade & Butcher was the most popular brand of straight razor, the weapon of choice for minstrel-show comedy. some gems and oddities over the years. This was his first attempt to compose a multi-section rag, and his paean to the room that was his professional home for much of the 1960s: the Gaslight Cafe on MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village.

some gems and oddities over the years. This was his first attempt to compose a multi-section rag, and his paean to the room that was his professional home for much of the 1960s: the Gaslight Cafe on MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village. Patrick Sky and Phil Ochs were on the scene it was no longer “Mitchell’s cafe.” But Dave was its reigning star for much of its heyday, doing feature nights and hosting a regular Tuesday evening hootenanny (what we’d now call an open mike), and if some facts are jumbled, the song conveys his wry affection for a unique time and the place he described as “my office and second home.”

Patrick Sky and Phil Ochs were on the scene it was no longer “Mitchell’s cafe.” But Dave was its reigning star for much of its heyday, doing feature nights and hosting a regular Tuesday evening hootenanny (what we’d now call an open mike), and if some facts are jumbled, the song conveys his wry affection for a unique time and the place he described as “my office and second home.” Dave’s years at the Gaslight are described at length in

Dave’s years at the Gaslight are described at length in  guitarists, and blues singers. It was a place where you could see a double bill of Skip James and Doc Watson one night, Len Chandler and a Middle Eastern group the next, and then Mississippi John Hurt with Dave and Paxton opening… and I was three years old and two hundred miles away. If anyone invents a time machine, book me passage.

guitarists, and blues singers. It was a place where you could see a double bill of Skip James and Doc Watson one night, Len Chandler and a Middle Eastern group the next, and then Mississippi John Hurt with Dave and Paxton opening… and I was three years old and two hundred miles away. If anyone invents a time machine, book me passage. New England Conservatory Ragtime Ensemble, and suchlike, Dave took up the challenge and began arranging more classic rags. Among them, not surprisingly, was Scott Joplin’s masterpiece, “The Maple Leaf Rag,” which Dave recorded on his Sunday Street LP. However, when I interviewed him about this he said he never really saw himself as a ragtime instrumentalist:

New England Conservatory Ragtime Ensemble, and suchlike, Dave took up the challenge and began arranging more classic rags. Among them, not surprisingly, was Scott Joplin’s masterpiece, “The Maple Leaf Rag,” which Dave recorded on his Sunday Street LP. However, when I interviewed him about this he said he never really saw himself as a ragtime instrumentalist: accompaniments for songs. Which is what I do do.”

accompaniments for songs. Which is what I do do.” racial protest novel from 1930, Gilmore Millen named it along with “Pallet on the Floor,” “Stavin’ Chain,” and “The Dozens” as “forerunners of the blues, at least in honk-a-tonk popularity, those old songs crammed with Anglo-Saxon physiological monosyllables and lascivious purpose.”

racial protest novel from 1930, Gilmore Millen named it along with “Pallet on the Floor,” “Stavin’ Chain,” and “The Dozens” as “forerunners of the blues, at least in honk-a-tonk popularity, those old songs crammed with Anglo-Saxon physiological monosyllables and lascivious purpose.” Fortunately, the underlying “lascivious purpose” survived expurgation in versions by Lipscomb and Rev. Gary Davis, which also provide eloquent testimony to how widespread the song must have been, since Davis was from the Carolinas and Lipscomb was in Texas, but they not only shared some lyrics but played variations of the same guitar accompaniment.

Fortunately, the underlying “lascivious purpose” survived expurgation in versions by Lipscomb and Rev. Gary Davis, which also provide eloquent testimony to how widespread the song must have been, since Davis was from the Carolinas and Lipscomb was in Texas, but they not only shared some lyrics but played variations of the same guitar accompaniment. around-the-neck bass notes for the opening D chord, while he just played open strings. He added, “It sounds nice that way. Keep it.” So I have.

around-the-neck bass notes for the opening D chord, while he just played open strings. He added, “It sounds nice that way. Keep it.” So I have.