Respecting the Blues Makers

by Elijah Wald

[Home] [Elijah Wald Bio] [Robert Johnson] [Josh White] [Narcocorrido] [African Guitar]

[Other writing] [Music and albums]

[Dave Van Ronk]

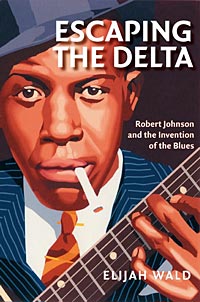

(This piece, which was originally published in Living Blues magazine in 2003, is a shorthand version of an argument made at much greater length in my book, Escaping the Delta.)

This has been declared the “Year of the Blues” -- not,

we are told, because Martin Scorcese is producing a documentary series

on the music, but because this is the hundredth anniversary of the first

reported blues sighting. Back in 1903 or so, W.C. Handy heard a down-and-out

guitar player at a train station in the Mississippi Delta, sliding a

knife along the strings of his guitar and singing about “Going

where the Southern cross the Dog.” As it happens, there are earlier

reports of songs that are more clearly blues, such as Jelly Roll Morton’s

of hearing the New Orleans singer and pianist Mamie Desdumes sing “2:19,”

a perfect example of the 12-bar form, or Ma Rainey’s of hearing

a young woman in Missouri in 1902. The problem with such reports is

that they do not fit the stereotype beloved of modern blues fans: the

ragged, male, Mississippi Delta slide guitarist.

This

stereotype did not grow by itself. It has been carefully nurtured since

the first time rural blues was introduced to a large white audience.

That was back in 1938, when John Hammond Sr. produced the first “Spirituals

to Swing” concert at Carnegie Hall. Mostly, this concert consisted

of live music, but Hammond played records of two performers: One was

an African group, presented as an example of the roots of African-American

music. The other was a rather atypical sample of Robert Johnson. Johnson

had recorded 29 songs, all but a handful in the currently popular urban

styles of Kokomo Arnold, Leroy Carr, Peetie Wheatstraw, Tampa Red and

Lonnie Johnson, but at the end of his first session -- probably after

running out of his prepared recording material -- he had tossed in a

few songs he had learned back in his teens from a local juke joint musician

named Son House, and these were the songs Hammond played for the Carnegie

Hall audience.

This

stereotype did not grow by itself. It has been carefully nurtured since

the first time rural blues was introduced to a large white audience.

That was back in 1938, when John Hammond Sr. produced the first “Spirituals

to Swing” concert at Carnegie Hall. Mostly, this concert consisted

of live music, but Hammond played records of two performers: One was

an African group, presented as an example of the roots of African-American

music. The other was a rather atypical sample of Robert Johnson. Johnson

had recorded 29 songs, all but a handful in the currently popular urban

styles of Kokomo Arnold, Leroy Carr, Peetie Wheatstraw, Tampa Red and

Lonnie Johnson, but at the end of his first session -- probably after

running out of his prepared recording material -- he had tossed in a

few songs he had learned back in his teens from a local juke joint musician

named Son House, and these were the songs Hammond played for the Carnegie

Hall audience.

Fast-forwarding to 1961, the first Robert Johnson LP was released by

Columbia Records, and served as inspiration for a generation of young,

white blues and rock musicians on both sides of the Atlantic. Again,

this album reflected a very different assessment of Johnson’s

art than might have been expected by anyone in the blues world. Over

the previous decades, two of Johnson’s songs had become established

as popular blues standards: “I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom,”

through a version by Elmore James, and “Sweet Home Chicago,”

recorded by numerous artists including Junior Parker, whose recording

had turned it into a Chicago barroom favorite. Neither of these songs

were included on the Columbia LP. Instead, it had every song with rural

Delta roots that Johnson had happened to record, including a couple

that had been withheld from release in the 1930s (presumably because

they were so out of touch with contemporary blues tastes). Thus, a young

man who had been considered one of the hippest, most forward-looking

musicians on his local scene was reinvented as a Delta roots revivalist

-- a fine example of apostles creating a god in their own image.

It can be argued, very reasonably, that Hammond and Columbia were doing

Johnson a favor. Most current fans of his work would probably agree

that Johnson was at his most powerful when he was closest to his teenage

passion for Son House, and weaker when he was coming nearest to the

pop-blues trends of the mid-1930s. But maybe, in this historic “year

of the blues,” it is a good time to revisit the way we have seen

the music, and ask how much relationship it bears to the way the musicians

themselves, and their original fans saw it. Because, while the arbiters

of blues taste have all kinds of good arguments on their side, they

have also severely altered and limited the reputations of some very

talented artists.

A good place to begin this reassessment might be the CD Vanguard has

just issued of “Rare and Unreleased” recordings made in

the 1960s by Skip James. James was one of the greatest bluesmen to be

“rediscovered” during the folk-blues revival, and for a

lot of listeners (myself included), he was the deepest of all the Delta

singers. Other Delta musicians could be considered rowdy showboaters,

juke joint entertainers whose music somehow transcended its barroom

roots. James was something else: it was impossible to imagine people

getting drunk and kicking up their heels to moody meditations like “Devil

Got My Woman,” “Cypress Grove,” or “Washington

DC Hospital Bed Blues.” James was the haunted, existential bluesman

par excellence -- even Johnson had attained his deepest, most tragic

performance, “Hellhound On My Trail,” by imitating James

-- and the fact that he attracted fewer new fans than more accessible

figures like Mississippi John Hurt only reinforced this reputation.

A good place to begin this reassessment might be the CD Vanguard has

just issued of “Rare and Unreleased” recordings made in

the 1960s by Skip James. James was one of the greatest bluesmen to be

“rediscovered” during the folk-blues revival, and for a

lot of listeners (myself included), he was the deepest of all the Delta

singers. Other Delta musicians could be considered rowdy showboaters,

juke joint entertainers whose music somehow transcended its barroom

roots. James was something else: it was impossible to imagine people

getting drunk and kicking up their heels to moody meditations like “Devil

Got My Woman,” “Cypress Grove,” or “Washington

DC Hospital Bed Blues.” James was the haunted, existential bluesman

par excellence -- even Johnson had attained his deepest, most tragic

performance, “Hellhound On My Trail,” by imitating James

-- and the fact that he attracted fewer new fans than more accessible

figures like Mississippi John Hurt only reinforced this reputation.

It must be admitted, though, that the records made of James in the 1960s

also revealed him as a very limited artist. Over and over, on various

blues collector labels, he recut the same dozen songs, largely remakes

of the songs he had recorded at his one session in the early 1930s.

He was often magnificent, but the difference between one James album

and another was measured in how well he was playing and singing on any

particular day, not in the variety or imagination of the material.

So, what am I to make of this new Vanguard release, which has a bunch

of songs that have appeared on no other album, including some in styles

that are quite different from anything I ever knew him to play? A few

years ago, the Genes Vault label released an album with James’s

version of Hoagy Carmichael’s laconic pop classic, “Lazy

Bones,” and it seemed like a startling anomaly in his repertoire,

an eccentric divergence that charmed me, but forced no fundamental reassessment

of James’s art. The new CD has another take of “Lazy Bones,”

but here it fits a larger pattern. The album starts with a cover of

Bessie Smith’s great hit, “Backwater Blues,” and includes

James’s takes on Lemon Jefferson’s “One Dime Blues”

and “Jack of Diamonds,” and Brownie McGhee’s “Sporting

Life Blues.” Two songs, “Omaha Blues” and “Somebody

Loves You” are piano numbers in a vaudevillian pop vein, the latter

verging on a Nashville country weeper. “My Last Boogie”

is more typical of the James I knew, but uses his quirky approach to

created a guitar version of the piano standard, “Cow Cow Blues.”

There has to be a reason why these tracks were not released twenty-five

years ago, and it cannot just be a question of quality. They sound fine,

and by any standard were more deserving than some of the less-inspired

takes of James’s oft-repeated “classics.” I can only

conclude that they were held back for exactly the reasons that I wish

they had been available: because they showed a more varied and ambiguous

artist than the haunted mystic we knew and worshipped. That is, they

suggest that James was not a Delta Van Gogh, creating personal masterpieces

in opposition to the accepted mainstream, but an adept professional,

willing and able to assimilate the trends of his time.

Or, to put it differently, the young record collectors who brought James

to a new audience had gone out in search of the man who recorded “Devil

Got my Woman,” and that is who they found and presented. They

would not have traveled to the Delta to find a piano player who could

please bar crowds with his covers of studio products from Chicago and

New York, and they had little or no interest in that facet of James’s

repertoire.

In this, the young white blues fans were very much like the Delta audiences

of James’s heyday. Both wanted to hear music that carried them

out of their day-to-day lives, and brought them the sounds of a magical,

distant world. For white New Yorkers, that world was the dark, mysterious

Delta. For Depression-era black Delta farmers, it was the fabled metropolises

up north. As a seasoned pro, James was able to suit either demand.

Of course, some artists have resisted audience pressures, but this brings

its price. Take Lonnie Johnson. When the rediscoverers came his way,

he was working as a janitor and badly needed the extra income that concerts

could bring, but he also had his pride. Unlike Big Bill Broonzy, who

had learned a new repertoire of old folk-blues in order to play the

part of an Arkansas sharecropper, Johnson insisted on playing electric

guitar and singing things like “Red Sails in the Sunset”

and “I Lost my Heart in San Francisco.” He was prouder of

the records he had made as a soloist with Duke Ellington’s orchestra

than the ones he had done as accompanist to Texas Alexander, and prouder

of his romantic Number One R&B hit from 1948, “Tomorrow Night,”

than of a forgotten blues about bedbugs he had cut back in the 1920s.

As a result, he found few listeners on the blues revival scene, though

he was appreciated by a small coterie of trad jazz fans.

Of course, some artists have resisted audience pressures, but this brings

its price. Take Lonnie Johnson. When the rediscoverers came his way,

he was working as a janitor and badly needed the extra income that concerts

could bring, but he also had his pride. Unlike Big Bill Broonzy, who

had learned a new repertoire of old folk-blues in order to play the

part of an Arkansas sharecropper, Johnson insisted on playing electric

guitar and singing things like “Red Sails in the Sunset”

and “I Lost my Heart in San Francisco.” He was prouder of

the records he had made as a soloist with Duke Ellington’s orchestra

than the ones he had done as accompanist to Texas Alexander, and prouder

of his romantic Number One R&B hit from 1948, “Tomorrow Night,”

than of a forgotten blues about bedbugs he had cut back in the 1920s.

As a result, he found few listeners on the blues revival scene, though

he was appreciated by a small coterie of trad jazz fans.

As it happens, Lonnie Johnson was a much more important figure than

Robert Johnson or Skip James in the evolution of blues. He was the main

inventor of “lead guitar,” creating a dynamic, single-string

style that was idolized by younger players from Robert J. to B.B. King,

and is thus ancestor to all the guitar heroes to come. This is a fact

acknowledged by all historians, though some will add that unfortunately

he was handicapped by a light, smooth, pretty vocal style that was not

really suited to blues material.

Having written a biography of Josh White, I am obviously not someone

who is discouraged by smooth, pretty singing. And yet, I grew up in

the blues revival and share many of its tastes. I prefer Son House’s

singing to Lonnie Johnson’s, as I prefer Howlin’ Wolf’s

to Nat King Cole’s, and Tom Wait’s to Paul McCartney’s.

In my little world, these are common tastes. I am aware, though, that

in the big world of popular music they are the tastes of a tiny minority.

Once upon a time, blues was popular music. The popular music of a minority,

it is true, but a minority made up of the mass of African American record

buyers (plus a good many whites, especially in the South), not a select

handful of cognoscenti. Look through the record ads in the Chicago Defender,

the country’s most popular black newspaper, during the 1920s.

There is an occasional ad for a jazz instrumentalist, but the overwhelming

majority, then as now, are for singers, almost all of them blues singers.

Judging by these ads, Louis Armstrong was the only major black recording

star who was not primarily singing blues. And who were the biggest stars?

Most were still women, who had dominated the field ever since Mamie

Smith broke out with “Crazy Blues” in 1920. Among the men,

the most popular names by far were Lemon Jefferson and Lonnie Johnson.

Jefferson was generally shown as an old-time Southern guitar picker

and singer. (His music was described as “down home.” ) Johnson,

by contrast, was sold as a pure blues singer, the one male vocalist

rivaling the theatrical “blues queens” on their own turf.

Not one of his ads even hinted that he played guitar.

Jefferson was from Texas, Johnson from New Orleans. Among the biggest

male blues stars of the 1920s, Charlie Jackson was from New Orleans,

Blind Blake and Barbecue Bob from around Georgia, Jim Jackson from Memphis.

Except for Johnson, all could be considered more or less “down

home,” and history books tend to cite such musicians as the key

figures in early blues -- though the two Jackson’s are often described

as minstrel or “medicine show” players rather than straight

bluesmen. The fact that Lonnie Johnson -- the one sophisticated, mainstream

pro -- remained a force in black popular music for three decades, while

the others saw their recording careers rise and fall in a half-dozen

years, is rarely emphasized.

As for the blues queens, who dominated the profession throughout the

1920s and always remained a major force as far as black audiences were

concerned -- Dinah Washington, Laverne Baker, and Aretha Franklin were

among many who carried on the reign -- they are commonly thought of

as outside the mainstream of later blues history. This reflects the

simple fact that “blues,” as a category of black show business,

has for many years been a synonym for “chitlin’ circuit”

or other such low-paying musical ghettos. Bessie, Mamie, and Clara Smith

were foremothers to Billie Holiday, Washington, Ruth Brown, Franklin,

Nina Simone, and eventually Whitney Houston and India.Arie -- a popular

enough strain of the blues world to be reclassified as jazz, soul, and

r&b. Lonnie Johnson’s male equivalent of this strain was carried

on by Billy Eckstine, Nat Cole, and George Benson -- again, with a degree

of success that lifted it out of the blues category.

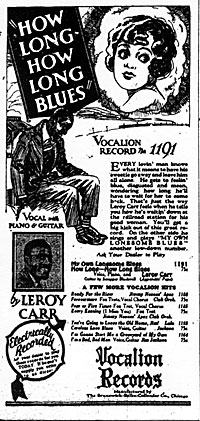

Which brings us to the mainstream of what is currently considered blues,

and the single most influential figure in its history. This was the

man whose followers dominated the blues market throughout the 1930s

and 1940s, and permanently reshaped the music’s identity. Never

again would blues be primarily a music sung by elegant divas in theaters,

or by streetcorner songsters. Instead, it became a solid, small-combo

style, fitting the growing urban black public and thrilling small-town

kids throughout the South with its promise of a better life in St. Louis,

Chicago, or Harlem. The man who inspired this transformation, and the

key figure in blues as we know it, was Leroy Carr.

I

do not think any serious blues historian will dispute Carr’s primacy,

if what we are talking about is blues as black popular music rather

than folk art. Of course, he was not alone -- Tampa Red and Big Bill

Broonzy were moving in the same direction, and became the most prolific

blues record-makers of the 1930s -- but he was clearly the most influential.

Once again, as with Bessie Smith and Lonnie Johnson, he had many followers

who escaped the blues ghetto: Count Basie recorded a half-dozen Carr

compositions and hired the Carr-flavored Jimmy Rushing as his band’s

first singer. Nat Cole, when he sang blues, came straight out of the

Carr camp, and Ray Charles paid tribute with several Carr covers among

his early sides. Vocal groups from the Ink Spots to the Dominoes harmonized

on Carr numbers, and Chuck Berry, with his suave, urbane take on a later

blues scene, was a direct descendent. As for soul stylists, let me quote

the R&B historian Arnold Shaw: “[Sam] Cooke, who influenced

Otis Redding, David Ruffin, and Jerry Butler . . . was himself the culmination

of a blues-ballad tradition that had its inception with Leroy Carr and

numbered Cecil Gant, Charles Brown, and Dinah Washington among its celebrated

exponents.” (For those who would say that Cooke was more indebted

to gospel than blues, here are the words of his mentor in the Soul Stirrers,

R.H. Harris: “[Carr] was my man. I just wished he’d been

in the spiritual field.”)

I

do not think any serious blues historian will dispute Carr’s primacy,

if what we are talking about is blues as black popular music rather

than folk art. Of course, he was not alone -- Tampa Red and Big Bill

Broonzy were moving in the same direction, and became the most prolific

blues record-makers of the 1930s -- but he was clearly the most influential.

Once again, as with Bessie Smith and Lonnie Johnson, he had many followers

who escaped the blues ghetto: Count Basie recorded a half-dozen Carr

compositions and hired the Carr-flavored Jimmy Rushing as his band’s

first singer. Nat Cole, when he sang blues, came straight out of the

Carr camp, and Ray Charles paid tribute with several Carr covers among

his early sides. Vocal groups from the Ink Spots to the Dominoes harmonized

on Carr numbers, and Chuck Berry, with his suave, urbane take on a later

blues scene, was a direct descendent. As for soul stylists, let me quote

the R&B historian Arnold Shaw: “[Sam] Cooke, who influenced

Otis Redding, David Ruffin, and Jerry Butler . . . was himself the culmination

of a blues-ballad tradition that had its inception with Leroy Carr and

numbered Cecil Gant, Charles Brown, and Dinah Washington among its celebrated

exponents.” (For those who would say that Cooke was more indebted

to gospel than blues, here are the words of his mentor in the Soul Stirrers,

R.H. Harris: “[Carr] was my man. I just wished he’d been

in the spiritual field.”)

Carr was a singer, songwriter, and pianist, born in Nashville but raised

and permanently based in Indianapolis. He made most of his records in

a duo with a fine guitarist, Scrapper Blackwell, though Blackwell’s

name was listed on only about a quarter of their releases. They were

versatile musicians, capable of playing everything from older black

styles to the latest Tin Pan Alley pop, but their most influential songs

were blues ballads: “How Long, How Long,” “Midnight

Hour,” “(In the Evening) When the Sun Goes Down,”

“Mean Mistreater Mama.” As a songwriter, Carr was one of

the most eloquent poets of the 12-bar form, crafting thoughtful, evocative

compositions, quite unlike the conglomeration of mix-and-match verses

that were common among more countrified singers.

Imitators flocked to capitalize on Carr’s success -- one of the

most popular blues artists of the 1930s, Bill Gaither, even adopted

the nickname “Leroy’s Buddy.” His impact was similar

to that of Bing Crosby in the white pop world. Both were “crooners,”

and their arrival signaled a change not only in vocal fashions but in

technology and the way people related to music. Before, entertainers

had needed big voices as a basic necessity of their trade: without volume,

they could not be heard. Now, records and radio were bringing music

into people’s living rooms, while microphones allowed singers

to project intimate, conversational tones. Furthermore, as Thomas Dorsey,

the blues pianist who became the “Father of Gospel Music,”

would point out, people were moving to the city and much of the work

was now at parties in apartment buildings, where brass instruments or

leather-lunged shouters would provoke complaints from the neighbors.

The Carr-Crosby connection was not simply a matter of parallel evolution.

Crosby’s crooning style was a revolutionary, overpowering force

in American popular singing, and no one who has heard Carr’s recording

of Irving Berlin’s “How About Me” can doubt that he

considered himself part of this new wave. Carr’s gently melodic

pop voice, a lighter variant of his blues ballad style, comes down to

us on only a half-dozen records, and these have rarely been included

on blues reissue albums. That makes some sense, as they do not sound

like blues -- but then, it is only an accident of the commercial recording

market that we even have such categories.

We think of people like Lonnie Johnson and Leroy Carr -- or even Bessie

Smith, Robert Johnson, Skip James -- as blues singers because that is

what they recorded back in the 1920s and 1930s. Not because that is

what they played, but because that is what they recorded. The full range

of music in their live performances, and how they chose to balance their

sets, will never be known, but for all of them blues was part of a broader

mix. Those were the days before jukeboxes and sound systems had become

common, and a live entertainer was expected to play all the various

styles that his or her audience cared to hear. Plenty of people have

always wanted the latest hits, so those would make up much of any professional

musician’s repertoire, from street singers to band and vaudeville

stars.

The record companies were a different story. With Crosby, Rudy Vallee

and their ilk cutting thousands of records, there was no market for

discs of African-American guitar-piano duos playing Irving Berlin. (The

same held for other styles as well: There were Italian bands to cut

Italian music, so there was no need to record black string players like

Charlie McCoy or Howard Armstrong playing their repertoire of Neapolitan

mandolin favorites.) For recording, such musicians were generally expected

to come up with their own material. H.C. Speir, the Jackson, Mississippi

furniture store owner who arranged for almost all the Delta bluesmen

to do their early recordings, used to tell them that they needed four

original songs in order to do a session. As a result, someone who made

his living singing Leroy Carr numbers in his local juke joint -- and

in the 1930s there was probably not a single blues guitar or piano man

who did not play “How Long, How Long” -- needed to come

up with something different if he hoped to make any records. The result

is that we are left with thousands of recordings of original blues songs

by black guitar and piano players, and it is not surprising that we

think of this as their usual music. In some cases, this was undoubtedly

true; in many, it was undoubtedly not. Like musicians everywhere, they

were a varied bunch, with all kinds of tastes and inclinations.

And so it continued, more or less, up until blues ceased to be a major

force in African-American entertainment. T-Bone Walker, who started

out as a note-perfect Carr imitator, would play songs like “Stardust”

at his concerts, but recorded only blues. Junior Wells and Buddy Guy

made a good part of their living on the South and West Sides of Chicago

covering the latest hits of James Brown and Wilson Pickett, but their

recordings (and their concerts for white blues fans) featured a straight

blues repertoire. Ruth Brown dreamed of singing standards a la Billie

Holiday, but got typed as a blues shouter. And the mass-market electric

blues stars are not alone in this: when you hear John Cephas sing a

pop ballad like “Shanty in Old Shanty Town,” it is obvious

that he is at least as comfortable with this sort of material as with

the blues numbers that draw his fans.

There is a point to retracing this history: Blues is one of the great

American popular music styles, not an obscure back-country folk art.

There have been plenty of back-porch blues pickers, just as there have

been plenty of garage rock bands, but they were never the music’s

driving force. Its most influential figures have been practiced professionals,

whose breadth of talent and immersion in the currents of their times

allowed them to reach beyond a small cult audience. Like any other artists,

they should be judged by the taste, skill, and power of their work,

not by some mythical standard of “authenticity.” A monotonous

musician whose resume is spiced with murder convictions and jail terms

is no “realer” a bluesman because of that. He is just a

boring musician with some other problems on the side. Meanwhile, an

expert, interesting musician is not in any way stepping outside the

most authentic blues tradition by appearing onstage in stylish clothes,

using a crew of polished sidemen, and exploring other musical forms.

Of course, some of the greatest musicians of the last century

were unknown, poor, and had little or no professional success. Robert

Pete Williams, for example, did time for murder and never could make

a decent living from music. He was also a great artist, and his art

was undoubtedly informed by his personal experiences (as well as by

his admiration for Peetie Wheatstraw). Was he a major bluesman? To me,

yes, but I cannot name another major musician who was influenced or

inspired by him. His place in the history of blues is as a brilliant

footnote, alongside Leadbelly, another singer who had no impact on the

blues world, however much he may have thrilled generations of folk and

rock listeners.

As blues fans, we owe it to ourselves to follow our own tastes, but we owe it to the musicians to appreciate their skills, not to force them into cramped stylistic boxes or treat them like magnificent monsters. And we owe it to history to try to understand the truth about how the music grew and evolved, not to create romantic fictions about prisons, misery, and Devils at the crossroads.

©2003 Elijah Wald (originally published in Living Blues)