|

Leroy Carr - The Bluesman Who Behaved Too Well

|

||||

|

[Home

] [Elijah Wald Bio] [Robert Johnson] [Josh White] [Narcocorrido] [African Guitar] [Other writing] [Music and albums] [Dave Van Ronk] WHAT do you picture when you hear the word "blues"? A lone vagabond walking a dusty road in the Mississippi Delta? A gruff giant shouting over the noise of a Chicago bar? An outlaw guitar hero squeezing fiery notes from his Stratocaster?

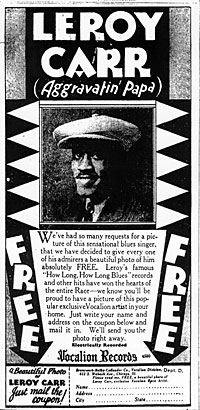

This sketch makes perfect sense if you follow it backward. The rock scene has always equated primitivism with authenticity, and it is logical that it would latch onto the grittiest, least polished blues artists as its forebears. Likewise, people in search of an African-American folk heritage are naturally drawn to the music's most archaic-sounding performers. But before blues was marketed as roots or folk music, it was a vibrant black pop style, and its original audience had very different standards from those of most modern-day fans. While today's blues lovers look back to rural Mississippi, black Americans at the height of the blues era were looking forward to Harlem and "sweet home Chicago." This split is perfectly exemplified by the two audiences' reactions to Leroy Carr. Carr was the most influential male blues singer and songwriter of the first half of the 20th century, but he was nothing like the current stereotype of an early bluesman. An understated pianist with a gentle, expressive voice, he was known for his natty suits and lived most of his life in Indianapolis. His first record, "How Long — How Long Blues," in 1928, had an effect as revolutionary as Bing Crosby's pop crooning, and for similar reasons. Previous blues stars, whether vaudevillians like Bessie Smith or street singers like Blind Lemon Jefferson, had needed huge voices to project their music, but with the help of new microphone and recording technologies, Carr sounded like a cool city dude carrying on a conversation with a few close friends. Carr's lyrics were carefully written, blending soulful poetry with wry humor, and his music had a light, lilting swing that could shift in a moment to a driving boogie. Rather than Smith's vaudeville jazz combos or Jefferson's idiosyncratic country picking, Carr sang over the solid beat of his piano and the biting guitar of his constant partner Francis (Scrapper) Blackwell. The outcome was a hip, urban club style that signaled a new era in popular music. Given his importance, it was logical that when Columbia records had a surprise success in the early 1960's with Robert Johnson's "King of the Delta Blues Singers," the label followed up with a Carr compilation. It was titled "Blues Before Sunrise," after one of Carr's most popular songs, a haunting ballad that had been covered by John Lee Hooker, Elmore James and Ray Charles. But the folk and rock fans who hailed Johnson as a genius showed no interest in the Carr album. His music was dismissed as an overly smooth variant of Johnson's fiercer, more rural style, as if he were Pat Boone to Johnson's Elvis Presley. Never mind that Carr's first records predated Johnson's first recordings by eight years, or that Johnson's work showed an immense debt to Carr's innovations. Carr's suave, laidback style was not what the new audience wanted in a bluesman. Now Columbia Legacy has come out with a two-disc Carr set — the first major-label release of his work since the 1960's — and the title suggests that the company has learned its lesson. Rather than evoking a lonely sunrise, it quotes a rough and ungrammatical line from the obscure "Hustler's Blues": "Whiskey Is My Habit, Good Women Is All I Crave." This line was not original to Carr (it comes from Lucille Bogan's "Whiskey Cravin' Blues"), but it conjures up the right image: a hard-living precursor to Keith Richards.

These artists were trendsetting stars, not obscure geniuses playing in back-country juke joints, and they were regarded in their communities as symbols of success. In his heyday as a R & B hitmaker, Muddy Waters wore gorgeous suits, combed his hair in a high pompadour and appeared on all-star bills alongside the Clovers and the Harptones. It was only in his later years, when he was playing for largely white audiences that considered him a carrier of the deepest Delta blues tradition, that he came onstage in street clothes. It is no coincidence that the audience that hailed both Carr and Waters as up-to-date stars was overwhelmingly black, while the one that rejected Carr as over-sophisticated and reinvented Waters as a link to Robert Johnson was overwhelmingly white. Very few African-Americans have ever been nostalgic for Depression-era Mississippi, while the image of the Devil-haunted Delta bluesman has been a romantic touchstone for everyone from the Stones to the White Stripes. Maybe the time has come, though, when blues can escape its stereotyped mythology and Carr can assume his rightful place. The subtle eloquence of lyrics like "When the Sun Goes Down" helped bring a new simplicity and directness to pop writing. The lonesome passion of Carr's voice on songs like "Midnight Hour Blues" set the stage for Ray Charles. As for the roots of rock 'n' roll, the pounding piano and sharp guitar lines of "Sloppy Drunk" and "It's Too Short" sound like direct antecedents of Ike Turner and Chuck Berry. Of course, some listeners will always prefer solo guitar to piano combos, and Charlie Patton's hoarse country shout to Carr's more subtle phrasing — just as some prefer B. B. King to Little Richard, the Stones to the Beatles or Missy Elliott to Norah Jones. But those are matters of taste, not authenticity. In its heyday, blues was not an old-fashioned folk style. Like rap, it had deep traditional roots but also a dynamic, modern sensibility that revolutionized American music. And Leroy Carr led that revolution, smooth voice, piano, fine suits and all.

|

||||

Today,

most people think of blues as the ultimate roots music, the rawest,

earthiest sound America has produced. A typical sketch of its evolution

runs from the Delta growl of Charlie Patton through Robert Johnson to

the electric South Side bands of Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf and eventually

to the Rolling Stones and Stevie Ray Vaughan.

Today,

most people think of blues as the ultimate roots music, the rawest,

earthiest sound America has produced. A typical sketch of its evolution

runs from the Delta growl of Charlie Patton through Robert Johnson to

the electric South Side bands of Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf and eventually

to the Rolling Stones and Stevie Ray Vaughan. Carr died of an alcohol-related illness shortly after his 30th

birthday, so the title makes some biographical sense--but what made him a key figure in American music was his records,

not his lifestyle. His followers dominated blues for more than 20 years

and affected every aspect of the African-American pop scene. In Chicago,

studios filled up with piano-guitar duos and Carr clones like Bumble

Bee Slim and Bill Gaither (billed as "Leroy's Buddy"). In

Mississippi, Muddy Waters recalled "How Long" as the first

song he ever learned. In Kansas City, Count Basie recorded Carr's hits

as piano solos. On the West Coast, T-Bone Walker and Charles Brown made

Carr's smooth urbanity the hallmark of the L.A. style. In New York,

vocal groups from the Ink Spots to the Dominoes harmonized on Carr compositions.

Nat King Cole's first hit, "That Ain't Right," was a Carr-inflected

blues, and the R & B historian Arnold Shaw traced soul ballad singing

from Carr through Dinah Washington and Sam Cooke to Otis Redding and

Jerry Butler.

Carr died of an alcohol-related illness shortly after his 30th

birthday, so the title makes some biographical sense--but what made him a key figure in American music was his records,

not his lifestyle. His followers dominated blues for more than 20 years

and affected every aspect of the African-American pop scene. In Chicago,

studios filled up with piano-guitar duos and Carr clones like Bumble

Bee Slim and Bill Gaither (billed as "Leroy's Buddy"). In

Mississippi, Muddy Waters recalled "How Long" as the first

song he ever learned. In Kansas City, Count Basie recorded Carr's hits

as piano solos. On the West Coast, T-Bone Walker and Charles Brown made

Carr's smooth urbanity the hallmark of the L.A. style. In New York,

vocal groups from the Ink Spots to the Dominoes harmonized on Carr compositions.

Nat King Cole's first hit, "That Ain't Right," was a Carr-inflected

blues, and the R & B historian Arnold Shaw traced soul ballad singing

from Carr through Dinah Washington and Sam Cooke to Otis Redding and

Jerry Butler.