Elijah Wald – Blues pieces

[Home] [Bio] [Jelly Roll Blues] [Robert Johnson] [Dave Van Ronk] [Narcocorrido] [Dylan Goes Electric] [Beatles/Pop book] [The Dozens] [Josh White] [Hitchhiking] [The Blues] [Other writing] [Musical projects] [Joseph Spence]

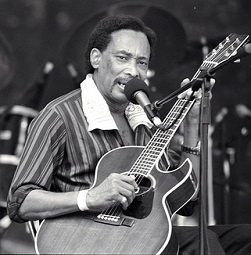

JESSE

FULLER PROFILE

©1997 Elijah Wald (originally published

in Acoustic Guitar)

Jesse Fuller was unique, and he worked hard at

keeping it that way. One of America's great musical nonconformists, he

played a big, 12-string guitar, chugging harmonica, raucous kazoo,

cymbal, washboard and fotdella, and called himself the "Lone Cat," a

romping one-man band. A singer, musician, composer, inventor and jack

of all trades, he was the Bay Area's greatest contribution to the

folk-blues revival, but his musical career reached a long way back

before "San Francisco Bay," the song that catapulted him to national

prominence.

Jesse Fuller was unique, and he worked hard at

keeping it that way. One of America's great musical nonconformists, he

played a big, 12-string guitar, chugging harmonica, raucous kazoo,

cymbal, washboard and fotdella, and called himself the "Lone Cat," a

romping one-man band. A singer, musician, composer, inventor and jack

of all trades, he was the Bay Area's greatest contribution to the

folk-blues revival, but his musical career reached a long way back

before "San Francisco Bay," the song that catapulted him to national

prominence.

Fuller was born in Jonesboro, Georgia, in 1896. He never knew his father and lost his mother when he was eight. Adopted by a local family, he was abused and neglected, and started working at an early age, breaking rocks in a quarry, toiling in a corn mill, carrying water for a railroad grading crew, and riding freight trains from job to job. At age ten, he also started playing guitar. As he later recalled, his first teacher was a woman who hung out around the railroad gang and went by the name of Big Estelle. "I'd go up there and watch her play and she was terrific," he remembered. "She didn't teach me all 'bout the guitar, just the chords, and I learned the rest myself."

As soon as he felt old enough to make it on his own, Fuller headed out of the deep South, looking for a better life. "Hell, I don't like the South at all," he told an interviewer in the 1960s. "If I were in the South now, . . . I'd be dead. I'm too color blind. Someone pushes me, I'll fight him, I don't care who he is." He first headed for Cincinatti, then got a job with a circus and began moving west. By the 1920s, he was in Hollywood, where he set up a shoe shine stand and, in the course of business, made the acquaintance of the movie star Douglas Fairbanks. Fairbanks set him up with a hot dog stand and gave him a Model T Ford, which Fuller "souped up like a race car." Fairbanks would sometimes hire Fuller to play at his private parties, and helped him get work as a movie extra, using him in "The Thief of Bagdad" among other pictures. As if all of that was not enough, Fuller developed still another sideline, carving amazingly lifelike wooden snakes, and worked his way through the depression selling them for a dollar apiece.

In 1929, Fuller moved up to Oakland, where he would live for the rest of his life. Once again, he worked a variety of jobs before making the decision to go into music as a full-time profession around 1950. At first, he tried to put a band together, but decided it was too much of a hassle. As he would later explain, "[The musicians] were all too busy--running around, drinking and gambling." Instead, he began rigging up ways to be his own accompanist. He put together a rack that could hold a harmonica, a kazoo and a microphone, and invented the fotdella, a six-string bass with a modified piano action that drove felt hammers against the strings. The fotdella, which he played with his shoeless right foot, was a visual novelty and gave his music a solid bottom, and he completed the rhythm section by using his left foot to keep time with either a sock cymbal or another homemade contraption that scraped a rubber arm across a washboard.

Thus was born the "King of the blues one-man bands." Fuller became a regular street performer around the Bay Area. The folk revival had not yet hit, but the West Coast was a hotbed for New Orleans jazz revivalists, and the trad fans were entranced by his music. He recorded his first album, a ten-inch LP called Working on the Railroad with Jesse Fuller, in the early '50s, and spent the rest of the decade bouncing around a variety of small, jazz-oriented labels.

The music Fuller played ranged from old work songs, hymns and spirituals to blues, ragtime and pop tunes. He was what blues fans call a "songster," a performer who could play and sing anything the audience wanted to hear. Whatever the style, though, once Fuller had rearranged it for his battery of instruments it bore his own unmistakeable stamp. Folklorists have sometimes tried to sort out the songs he wrote from those that were adapted from previous sources, but that is beside the point. Whether singing a folk ballad like "John Henry" or a pop chestnut like "Everybody Works But Father," he sounded only like Jesse Fuller.

Adept as he was at reshaping older material, Fuller always prided himself on his abilities as a writer. Al Young, the poet and novelist, who knew Fuller in the early '60s, recalls going over to see him at his sister's house in Oakland, and being shown his basement studio. "He went there every morning, and spent three hours writing his tunes," Young says. "He'd set up his fotdella and all of his stuff and sit there and compose with a tape recorder, and get his stuff down. Everybody thinks that he's a guy who just kind of casually knocked these things out, but he listened to everybody, he was very aware that the folk movement was his chance to be heard, and he would go down there every day and write. "

While the fotdella might be what stopped crowds on the street, what made Fuller a national figure was his songwriting, especially his masterpiece and theme song, "San Francisco Bay Blues." He recorded the song for every label that signed him, and soon it was covered by a plethora of young folkies, becoming a ubiquitous standard. With its success, Fuller took to the road, touring in a big Nash station wagon that also served him as a makeshift hotel, and playing coffeehouses, colleges and folk festivals across the country, then taking ship for a European tour during which, in his words, he "got more people than the Rolling Stones."

That choice of comparison says a lot about him. Unlike most of the older bluesmen who appeared on the folk circuit in the 1960s, Fuller was at home in the present, in tune with the contemporary scene and fully in charge of his life, music, and business. He knew what he was doing, and knew he was good at it, and it did not surprise him when the young, white folksingers started coming around to admire and learn from him. And learn they did. Bob Dylan's harmonica work shows more of Fuller's influence than anyone else's, and he paid tribute by recording Fuller's "You're No Good" on his first album. Mark Spoelstra used to drop by for guitar lessons. As for all the people who sang "San Francisco Bay," from Jack Elliott on down, there are simply too many of them to count.

Fuller died in 1976, but he left behind a lot of good music and good memories. Friends still tell stories about his quirky self-reliance, his insistence on driving everywhere, even to the point of refusing to go to Europe unless he could drive his car onto the boat and make the trip in his usual style, and the ingenuity with which he not only invented a slew of instruments but wired all of them so that he could plug the entire mass into a house p.a. system and wail away like a rock band. He was a true original and, two decades after his death, his music is still as exuberant and entertaining as anything on record.

Back to the Archive Contents page

PERRY LEDERMAN OBITUARY

©1995 Elijah Wald (originally published

in Sing Out!)

Perry Lederman, who died May 15 at his home in Woods

Hole, Massachusetts, after a long battle with cancer,

was one of the little-known legends of the folk revival.

Born in Brooklyn, NY, he was inspired to learn guitar

after seeing Tom Paley playing in Washington Square

Park and quickly became one of the foremost fingerstyle

players in the city, exploring and reviving traditional

styles in the company of friends like Danny Kalb and

Roy Berkeley. He was also a peerless seeker-out of vintage

3/4-size Martin guitars, which he continued to favor

throughout his life.

Perry Lederman, who died May 15 at his home in Woods

Hole, Massachusetts, after a long battle with cancer,

was one of the little-known legends of the folk revival.

Born in Brooklyn, NY, he was inspired to learn guitar

after seeing Tom Paley playing in Washington Square

Park and quickly became one of the foremost fingerstyle

players in the city, exploring and reviving traditional

styles in the company of friends like Danny Kalb and

Roy Berkeley. He was also a peerless seeker-out of vintage

3/4-size Martin guitars, which he continued to favor

throughout his life.

Perry continued to play during a brief college stint in Ann Arbor, Michigan, then moved to Berkeley, California, where he became a leading folk performer in partnership with writer and poet Al Young. His playing, notable for its passion and imagination, and an astonishing, controlled vibrato, was a major influence on later West Coast players like John Fahey and frequent housemate and jamming partner Michael Bloomfield. It was during this period that he made his only issued recording, on a Bay Area sampler for the Arhoolie label. More interested in the music itself than in commercial success, Perry put the guitar aside just as his West Coast followers began to receive national attention, preferring to spend eight years studying sarod as a student and friend of Indian master Ali Akbar Khan.

Returning to guitar, he brought depth and control learned in his Indian classical studies and applied these to the music he had always loved, the classic fingerpicking styles of Elizabeth Cotton, Gary Davis and Sam McGhee. In the early 1980s he came back East, and for the last 13 years lived in Woods Hole with his wife, Joan, and daughter, Rayna. He played mostly in his home and at the coffee house he booked at the Fishmonger Cafe, where he presented old friends like Dave Van Ronk and Rory Block. He also mastered the art of piano tuning, frequently teaming up with his musical companion and teacher, David Stanwood. His playing continued to grow and develop, as he constantly found new approaches to his favorite tunes.

Music was Perry's religion, be it Indian classical, traditional fingerpicking, or the gospel singing of Mahalia Jackson or Claude Jeter of the Swan Silvertones, who performed his marriage. He continued to play until the end, and the soulfulness and depth of his musicianship remained undiminished. In April he recorded some magnificent pieces for a planned album, and in the week before his death he gave a final brief concert from his bed for old friend Ramblin' Jack Elliott. All of us who had a chance to play with him and learn from him over the years will be forever grateful for his kean musical sense, his willingness to pass on whatever he knew, and his friendship.

During his last year, Perry and I compiled a CD of his work, drawing on his old tapes, concert recordings, and some new recordings he made to fill the gaps. It can be ordered from this site, by going to my music and albums page.

Back to the Archive Contents page

PAUL GEREMIA INTERVIEW

©1994 Elijah Wald (originally published

in Blueswire)

Among acoustic blues players, Paul Geremia is

virtually in a class by himself. While remaining within the country

blues tradition, he has developed a sound and approach that is

completely personal and contemporary. His singing mixes the influence

of Willie McTell and Lemon Jefferson with jazz phrasing and an edge of

wry humor. His harmonica lines have a punch and energy that few rack

players can approach. On guitar, he is quite simply the best acoustic

blues picker around; whether playing straight or slide, six or

twelve-string, he combines an encyclopedic collection of classic styles

with imaginative touches that are all his own.

Among acoustic blues players, Paul Geremia is

virtually in a class by himself. While remaining within the country

blues tradition, he has developed a sound and approach that is

completely personal and contemporary. His singing mixes the influence

of Willie McTell and Lemon Jefferson with jazz phrasing and an edge of

wry humor. His harmonica lines have a punch and energy that few rack

players can approach. On guitar, he is quite simply the best acoustic

blues picker around; whether playing straight or slide, six or

twelve-string, he combines an encyclopedic collection of classic styles

with imaginative touches that are all his own.

Geremia was interviewed in his Newport, Rhode Island home, in between refretting an old Gibson guitar and chatting with folk legend Ramblin' Jack Elliot, who had parked his mobile home in Geremia's lot for the night. Previous conversations had focused on Geremia's life and playing. This time, he set the agenda.

Anything particular you'd like to talk about?

Yes, I think it would be nice to see more attention paid to acoustic blues. I'm disappointed with the fact that the so-called blues resurgence pretty much pays lip service to the acoustic music and is basically centered around electric bands, a lot of which are much too loud and are just basically rock bands. It's reached a point where everybody's trying to capitalize on the blues thing.

So, what is it that you're not seeing enough of?

I'm not seeing enough of people digging deep. I'm not trying to say that I expect people to try to do what I'm trying to do-- it can be done both in the world of electric blues and in the world of acoustic blues. I'd rather see people digging into the older styles and coming up with a more unique electric sound, rather than sounding like a rehash of B.B. King or Albert King or, God forbid, Stevie Ray Vaughan. It seems like everybody's just picking up on what they did, instead of going back to develop a unique style like the originators had. But, then again, maybe there just isn't that much room for innovation in the music; maybe you innovate too much and it changes it. I'm curious as to whether we're just stuck with what we've got for the duration. Is it just gonna be a situation where we're gonna listen to Muddy Waters clones--which I wouldn't mind so much--or are there gonna be people who come up with something new?

I think it's unfortunate that the blues scene can't be as healthy as the bluegrass scene, for example. They've got people playing electric and acoustic instruments, running the gamut from singer-songwriters to traditional people to new age instrumental types. I get sick and tired of going to so-called blues festivals where basically people are there to get drunk and boogie to loud music. I mean, I like to get drunk and boogie too, but the acoustic players always get put on during the daytime and then the bands get put on at night. It's not fair to the audience and it's not fair to the acoustic musicians, because there are acoustic players who can get on there and blow people away in a night time concert, and acoustic instruments were meant to be danced to just as well. That's what the music was about. They didn't have to have amplifiers tuned up to maximum and have their eardrums busted in order to dance to it, you know?

Where do you see yourself and your work in all of this?

Well, I'm trying to write songs that remain true to the blues tradition and I'm still trying to learn more of the old styles.

Clearly, for you blues doesn't just mean the 12-bar form.

It's not just blues; I'm basically into old music. Stuff that was both played by black musicians and white musicians. There's a lot of stuff that was part of the blues tradition, like some of the country ragtime stuff and the early jazz stuff. The stuff that was played by the Mississippi musicians other than the guys that played blues was string band music; there were a lot of banjos and fiddles and all kinds of things going on down there.

I like it all, you know. I just find myself getting bored with hearing the same thing over and over again. I'd much rather hear interesting acoustic musicians than some skinny white guy with an electric guitar, playing it too loud and singing testosterone lyrics--this whole macho guitar gunslinger bullshit. I can't stand that; it's boring to me.

And there's so much else there. My basic complaint is that people seem to be recycling a lot of the same stuff when so much of the world of blues music has not been recycled at all. I guess it's because it's difficult stuff to learn, and it's easier to pick up on what's being played more frequently. If I was just learning, I might be in the same boat, I don't know.

When you were starting out, the blues scene was

much more a part of the folk scene, rather than a scene unto itself.

That's right, to a large extent. The folk revival was the crutch that the blues leaned on through the entire '60s and it brought the best blues music that was known to as many people as possible. Unfortunately, the folk situation now is pretty much dominated by the singer-songwriter tradition, but I think there's still a healthy interest in the acoustic blues.

It seems to me that you bring those parts together, whereas a lot of younger blues players or singer-songwriters are strictly in one or the other camp.

The singer-songwriter tradition seems to be wide open; some people sound like tin pan alley show tunes and some sound like Woody Guthrie. They come from incredible extremes. What I'm doing is another aspect of that; I'm just writing songs from a different musical orientation. But I consider myself lucky to be just as interested in the tradition from which my music springs, because I can also draw sustenance from the traditional music that I mix in with my own songs. I wouldn't want to be in the bag of these people who feel they have to do all their own material, because I think that is also very boring.

So what do you feel good about these days?

I feel good about the fact that the Mississippi Crossroads Blues Festival's coming up and I'll get a chance to see Eugene Powell down there again; he's one of the few older musicians who are still doing it. I feel good about the fact that I'm still alive and feel relatively healthy. And it's still fun. The new record has helped a lot, and it got nominated for a Handy award. I'm playing more festivals than ever before. I'm also real happy about the Bruno 12-string that I fixed up. That keeps me up; sometimes when I get depressed I just think about my guitar and it snaps me out of it. And I'm just having a good time playing. Despite all my complaints I'm really glad things are going well, I'm working enough, and my ears still work.

Back to the

Archive Contents page

LARRY JOHNSON

©1998 Elijah Wald (originally published

in The Boston Globe)

At this summer's King Biscuit Blues

Festival, in Helena, Arkansas, the bill included

many of the stars of contemporary blues. The most exciting

performance, though, came from a

man whose name was unknown to all but a few hard-core

aficionados. Larry Johnson, alone on

stage with an acoustic guitar, reminded the audience

of what the blues is all about, singing with

a depth, directness and passion that made most of the

other performers seem like they were just

clowning around.

At this summer's King Biscuit Blues

Festival, in Helena, Arkansas, the bill included

many of the stars of contemporary blues. The most exciting

performance, though, came from a

man whose name was unknown to all but a few hard-core

aficionados. Larry Johnson, alone on

stage with an acoustic guitar, reminded the audience

of what the blues is all about, singing with

a depth, directness and passion that made most of the

other performers seem like they were just

clowning around.

It was the sort of performance that has all but disappeared from the contemporary scene, and a surprise even to people familiar with Johnson's early work. He has been out of professional music or working in Europe for most of the last quarter century, and old fans were astonished by the way his voice has grown in richness and emotional power. Teo Leyasmeyer, manager of Cambridge's House of Blues, was so impressed that he is bringing Johnson in for two nights this month, on the 12th and the 26th, for special, early-evening, sit-down concerts (497-2229).

"I don't drink or smoke anymore and that does make a difference,'' Johnson says, from his Harlem home. "I would think that had something to do with the way I'm singing. But then again, as the years go by you get more serious in whatever you're doing and as the old saying say, practice make perfect. That power comes with time. It was nothing that I was looking for or expected, but I got a good number of years behind me now, and I guess it has developed.''

For those who have not seen him live, Johnson's reputation largely rests on one album, 1971's "Fast and Funky,'' recently reissued by the Baltimore Blues Society (poorly distributed, it is available from the Society at 410/ 329-5825). It is no exaggeration to call this the most satisfying acoustic blues record by any artist born after 1930, the only one that completely captures the spirit of the classic blues while still sounding utterly personal.

Johnson says that his unique style arose from his circumstances. Born in Georgia 60 years ago, he moved to New York in 1959 and fell in with a group of older Southeasterners including Brownie McGhee, Alec Seward and, most importantly, the Rev. Gary Davis. Davis was a musical giant, teacher of everyone from Blind Boy Fuller to a generation of young, white enthusiasts. Johnson often accompanied Davis on harmonica, mastered his intricate guitar style, and became to some extent his musical heir.

Johnson is the first to acknowledge that taking on Davis's ragtimey, acoustic sound was an unusual choice for a young African American. "When you take a look at the black guys, we have to do what pays off now,'' he says. "There's no mama and daddy to run to, of any wealth. They're becoming there now, like with the Guy Davises [the blues-playing son of Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee], but that's not my age group. So most of them went to the B.B. King styles and the styles that were paying off.

"Me, I didn't particularly care about that. I've always been the self-independent type person and I never was one to go with the crowd of my age. The way I got involved was just by being around Brownie and Davis and all of them, and it was just a way of life. I wasn't seeking to become an entertainer or seeking anything whatsoever. That just happened in my life.''

Johnson attracted some attention among 1960s blues revivalists, and recorded for several small labels, but his career never really took off and, by the mid-1970s, he had pretty much quit. "I wasn't getting the work that my competitors was getting, and I wasn't getting nothing out of performing,'' he says. "So I made a decision that I wasn't gonna wear myself out. I had rent to pay and food to buy and at that time I was married and had kids -- I eventually lost my family because I wasn't making a living. But I never did stop playing. Because by then it was a company keeper to me. It was very personal. But performing just had nothing in it. I mean, a lot of people wanted me to perform for nothing, but nothing leaves nothing.''

At times, Johnson cannot help

sounding bitter. He is openly contemptuous of most

latter-day blues players, and is painfully conscious

of not having received his due. The small

labels that recorded him never spent a lot of money

on production or promotion, and none of

his other albums lived up to the promise of "Fast and

Funky.'' On top of that, his outspoken

views have earned him a reputation for being angry and

hard to deal with.

"I'm a black man doing a black tradition that was done many years before me, and I'm just one of the ones that's still carrying it on the way it should be done. Now, who can like me for that, fine. Who dislike me for that, fine. But I see myself as one of the original pioneers of my day. I see myself like Moses carrying on the tradition until Christ get here.''

Johnson sees himself as part of a long line that is by no means limited to blues. "It's like James Brown, he's doing what Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson and any of them others -- Frederick Douglass -- did. He's standing up for the black tradition. That don't mean we're prejudiced; we are just standing up for what we are. Such as Hank Williams stood up for his side of the fence, so to speak. I admire a white man that stand up for white folks, and I admire a black man that stand up for black folks. All this crossing the fence thing, I don't particularly care for that.''Today, as with all acoustic blues players, Johnson is playing almost exclusively for white audiences, but that has in no way mellowed his stance. "I have a message to bring, and if the whites listen to it that's fine,'' he says. "As for black people, there is no way a generation of people could just totally forget about a heritage. Most all blacks are well aware of the blues. But whether they go hear it is another thing, because you got to say 65 percent of blacks really don't care to race-mix or to mingle that way. They can't enjoy themselves.

"Me, I don't even go to these festivals unless I'm on them. There's nothing for me to do, there's nobody for me to talk to. Now if these things were held in the ghetto you would see a difference. But they're not. They're being held on the outskirts of town or some little town where the blacks are outnumbered. You got to look at it that way.''

Whatever the audience, Johnson is quick to point out that he has always been a loner, and he will keep on making his music, his way. "I feel like I was chosen for this, by something higher than me,'' he says. "Like this is my calling whether I like it or not. The difficult thing, as I look back on it now, was for me to maintain with it after Davis and all those guys died off. But by then, I was in my late 30s, early 40s. I looked around one morning and I was too old to get a decent job. So I said 'What do I have to make it through this world?' The only thing I had was the guitar. So I had to make it work. And today it must work. That's why I'm determined every time I go out there, every time I put my hands on a guitar, to be just a little better than I was before.''

Back to the Archive Contents page

Big Bill Broonzy (written in 1999 for the Boston Globe)

By Elijah Wald

Blues music has two histories, one as pop music for a largely black audience and one as “folk” or art music for a largely white audience. In the first, the biggest stars of the pre-World War II era were Bessie Smith and a dozen other women singers, then Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson, Leroy Carr, and Chicago studio players like Tampa Red. In the second, the most familiar names are Leadbelly and Robert Johnson, neither of whom had much success with the African-American public.

Then there was Big Bill Broonzy, who straddled both worlds and, to do so, created two histories himself. One of the fascinating things about “The Bill Broonzy Story,” a three-CD set recently reissued by Verve, is that, as he sings and talks about his life, music, and fellow musicians, the picture Broonzy paints of himself is of an old-time Mississippi blues player, the guardian of a vanished tradition reaching back to slavery times. There is no suggestion that he only learned to play guitar after moving to Chicago, or that, before most of his white fans first heard of him, he was a recording star leading a crew of studio players and driving a Cadillac.

Broonzy started out as a country fiddler around Arkansas, and moved to Chicago after getting back from World War I. He worked various jobs before picking up the guitar and gradually turning himself into the king of the local blues scene. The discography of “Blues and Gospel Records 1890-1943” has ten fine-print pages of records he made under his own name, and he is listed as accompanist on recordings by 36 other artists. He was part of a virtual assembly line of musicians grinding out small-combo records for the Depression-era pop-blues market, often with piano and horn sections.

Then, in 1939, he appeared at Carnegie Hall on John Hammond’s “Spirituals to Swing” concert. He was introduced not as one of the biggest stars in Chicago, but as an ex-sharecropper from Arkansas, an exemplar of the back-country, primitive music that had given birth to jazz. In the later 1940s, when blues had largely fallen from fashion, Broonzy picked up on this image and began touring the United States and Europe as an old-time Mississippi bluesman, the only person still playing the true, country style.

Within a few years of Broonzy’s death in 1958, young blues enthusiasts would travel to Mississippi and “discover” a host of players with styles far more earthy and old-fashioned than his. After that, his reputation fell into a sort of limbo -- too “folk” (and too familiar to a previous generation of white intellectuals) to be considered with Robert Johnson as a proto-rock ’n’ roller, and too slick to be a genuine roots artist.

Both of these assessments are unfair, but especially the former. Broonzy, more than Johnson, is a clear precursor of the electric blues stars. His bands set the pattern for the later Chicago groups; indeed, he introduced Muddy Waters on the local scene, and Waters’ first LP recording was a set of Broonzy songs. As for rock ’n’ roll, Broonzy made the case clearly: “You hear Elvis Presley, you hearin’ Big Boy Crudup. You hear Big Boy, you hearin’ Big Bill. He was my man.” While Broonzy could be unreliable on occasion, that lineage is directly traceable on record.

“The Bill Broonzy Story” was recorded in 1957, just before Broonzy underwent a cancer operation that left him unable to sing. He still sounds wonderful, singing with warmth and power, and playing tasty, swinging guitar lines. The material ranges from spirituals and African-American folk songs to “Swanee River” and “Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home.” Roughly half the songs are pop blues, the music with which Broonzy became a star, though his introductions frequently emphasize his “folk” purity. He introduces one song by explaining that it is not the sort of thing that Waters, Smokey Hogg, Lightnin’ Hopkins, or even the folk favorite Brownie McGhee would sing. “You couldn’t pay one of them fellows to play a song like that,” he says. “You couldn’t sell it.”

While often acting the part of the country cousin, Broonzy is meticulous about crediting his popular peers. He traces songs back to both their authors and the stars who made them famous. His reminiscences of these now-mythic figures are one of the great pleasures of this set, at least to hardcore blues lovers. At times, he also gives subtle clues to his own commercial orientation, as in his explanation of how one writes a blues. You can take anything -- a knife, a box, an axe, or, of course, a woman -- and write a blues about it, he says: “It don’t take but five verses to make a blues; think of five things you can do with something . . . and you got a blues.” That number five is not folk tradition; it is the number of verses that would fit on a three-minute 78 single.

The “country” persona, while somewhat disengenuous, was also deeply rooted in Broonzy’s early life. He was born in the Delta in 1893, and grew up as the blues were taking form. When he talks about his grandfather, a banjo player who remembered slavery (“They didn’t call what they was playing blues . . . they called it reels”), about the links between religious and secular singing, or about long days working as a plowhand, he is speaking from personal experience. (Even if he draws some odd conclusions, as when he says that New Orleans musicians cannot sing blues because they grew up working sugar cane rather than cotton.)

It is important to note, as well, that Broonzy’s folksiness did not in any way include nostalgia for the Southern rural world from which he had eagerly escaped. His credits include some of the strongest anti-racist songs in blues history, and he knew exactly why the younger generation of black listeners were not interested in his sound. “The younger people say you’re crying when you’re singing like that,” he says. “Who wants to cry? Back in those days people didn’t know nothing else to do but cry, they couldn’t say about things that hurt them. But now they talks and they gets lawyers and things. They don’t cry no more, so that’s why they don’t play ‘em like this.”

Of course, for those more interested in hearing music than history, the real value of this set is in the 35 songs and instrumentals. Broonzy was well aware that these might be his final sessions, and he performs like a man creating a final testament. While the interviewer at times tries to direct the recording along predetermined lines, Broonzy tends to go his own way, and there is no artist in blues who could have created a document more varied and imaginative than this. His vocals are relaxed and sure, a direct extension of his speaking voice. His virtuoso guitar phrases answer and punctuate the singing, drive the rhythm of the upbeat tunes, and even underlie much of the conversation.

Today, with the resurgence of interest in acoustic blues, it is time that Broonzy received his due. He is not only one of the major artists in the field, he is the most important bluesman to leave anything like a full picture of his taste, repertoire and abilities. His 1930s recordings, many of which are available on CD, are well worth hearing, as is his later, more folk-oriented work, and his written reminiscence, “Big Bill Blues,” was recently reprinted. As a well-rounded view of his life and music, though, these three CDs are the perfect place to start.