Elijah Wald – Dave Van Ronk profile |

Back

to the Books and Other Writing page By Elijah Wald © 1996 (originally published in Sing Out!)

Over the next couple of years, I bought all of Van Ronk's records and, like hundreds of callow youths before me, dropped my Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger inflections and set out to master his style. Undaunted by my utterly dissimilar vocal equipment, I howled and whispered my way through "Cocaine Blues" in my best approximation of a Van Ronkian growl. My father still remembers it as the funniest thing he ever heard. Five years later I went off to New York for a year of college, simply to take guitar lessons from the great man. Then, as now, he was nurturing a steady stream of young pickers eager to learn from the man who invented classic ragtime guitar, taught Dylan to fingerpick, and reigned as musical mayor of Greenwich Village in the glory days of what he somewhat acidly remembers as "the great folk scare." (Others have used the phrase, but he lays strong claim to being the originator.) The first time I walked into Van Ronk's apartment, I was startled at how different it was from my worshipful imaginings. Instead of a rough bluesman, there was a large, soft-spoken gentleman in wire-frame glasses, peering up at me from the corner of an immense couch. The room was dominated by a modernist canvas depicting a sink, and a great carved bird of New Guinean origin flew off the lefthand wall over an antique gold clock in a glass bell. A globe glowed in the corner by the windows, which were brown from years of pipe and cigar smoke. The lesson went well, and there were many more. Often they ran on into hours of conversation and dinner, which Van Ronk would cook with the same care and scholarship he put into his guitar arrangements. Then the whiskey would come out and the talk would stop as he put on some music: Jelly Roll Morton or Duke Ellington, or Groucho Marx, or Phillipe Koutev's Bulgarian Ensemble (Twenty years before the rest of the world caught on to the "Mystere des voix Bulgares," Van Ronk based his song "Honey Hair" on one of their melodies.). After opening a second bottle of whiskey, he might pull out an oddity like his duet with the Bahaman guitarist Joseph Spence on "Santa Claus is Coming to Town." Then more talk, until the drink was finished and I would stumble out into the morning sun. These days, the couch has been replaced by another, equally huge. Andrea Vuocolo, who moved in in the early 1980s and married Van Ronk a few years later, has installed a concert harp in one corner of the room and insisted that the windows and a lot of other things get cleaned. The whiskey has been replaced by wine, and the evenings do not last quite as long. Van Ronk has lost over a hundred pounds and has reinvigorated his recording career on his old friend Sam Charters' Gazell label, which has released four albums including a career retrospective and a long-awaited set of swing standards. On the whole, though, this evening is like a lot of others. Van Ronk is ensconced in his customary seat, an ashtray near at hand. A good meal has been eaten, an experiment in replicating precolonial East Indian cuisine by using black pepper instead of chilis. We have been listening to his new album, "To All My Friends in Far-Flung Places," a two-CD collection of songs by old colleagues and acquaintances, and it has prompted a meditation on the singer/songwriter movement and the course of the contemporary folk music scene. As usual, Van Ronk has his own analysis of the situation and, as usual, it is phrased with the elegance of a man who considers conversation the sport of kings. "In the great war between traditionalists and singer/songwriter fans I am a hilariously amused spectator," he says, suiting his expression to his words. "I think this is a battle that should be fought to the death with inflated pigs' bladders. It's the moldy fig wars all over again, with each side more asinine than the other and each argument more asinine than the next." The aforesaid wars were fought between fans of traditional New Orleans jazz, the "moldy figs," and bebop modernists. In his youth, Van Ronk was a staunch moldy fig, flailing away at a tenor banjo in the rhythm section of the Brute Force Jazz Band. Having mellowed somewhat with the years, he is trying to avoid a descent into similar partisan bickering. He has a firm grounding in traditional folk music, he admires the work of many of the young writers, and he thinks it is high time people stopped taking sides and listened to the music. Which is not to say that he shies away from strong opinions. "I suppose in a sense what I'm trying to do [with this album] is rescue the singer/songwriter movement from its own richly deserved obscurity," he says. "That is to say, the movement isn't really about singers and songwriters; it's about personalities. But there are some good songs and what I'm trying to do is to deal with the songs, to string together some of this contemporary stuff that I think deserves attention. "You see, I think the singer/songwriter movement is a phenomenon with a big hole in the middle. It's doomed to fail aesthetically because nobody sings anybody else's songs. Anne Hills can write a song as beautiful as "Follow that Road," but nobody but Anne Hills is ever going to sing that goddamn song, unless she gets really lucky. And that's true of dozens and dozens of songs. In order to have a singer/songwriter movement you don't need simply good singer/songwriters; you need a host of interpreters" It is not that Van Ronk is urging a return to traditionalist purism, to scholarly explications of "Barbara Allen" and fake rural accents. He did his time in those ideological salt mines forty years ago. In fact, he says, "I have no special brief for quote, folk music, end quote. I'm a singer. I'm a musician. I'm interested in good songs regardless of their provenance." Indeed, Van Ronk has probably recorded in as many styles and genres as any artist around. A founder of the 1960s folk scene and mentor to at least three generations of New York singer/songwriters, he has also recorded albums of both New Orleans and swing jazz, two jug band records, and one of Bertholt Brecht songs. And that is not to mention his stint with Paul Clayton and the Fo'c'sle Singers, or his recent jug band recording of Peter and the Wolf. Van Ronk likes to call himself a "cabaret singer," recalling not only French interpretive artists like Aristide Bruant, but also the sort of musically expansive shows Josh White and others did at Cafe Society and that Blossom Dearie, who lives just down the hall, continues to do today. And yet, when other people look for an adjective to describe him, they always seem to settle on "blues singer." It is a label that by now he can only regard with wry resignation. "Like it says in the gospel, the poor you have always with you," he says. "I mean, people in music don't listen. That means they're just like everybody else. I was tagged as a blues singer, incorrectly, back in 1950-what, and now I could go and sing 'Pagliacci' and I would still be called a blues singer. "Go back to the sixties and seventies. I was recording with traditional jazz bands. I was doing Brecht-Weill things. I had a rock band [The Hudson Dusters.] I believe I was the first person ever to record a Dylan tune. I was the first person to record a Joni Mitchell tune, or certainly one of the first. I've recorded Jacques Brel. "My track record over the last thirty years is quite consistent: I've always been inconsistent. If people want to think of me as a blues singer, as some sort of albino Muddy Waters or something like that--well, they're entitled. But my rule has always been, anything that I like and that I think I can find a handle to, I'll take a whack at. And as it has been so shall it be." Van Ronk has found that such eclecticism can present a problem in the ever more format-conscious world of commercial music-making. "Record companies always worried, because they didn't know how to pigeon-hole me," he says. "And I used to tell them 'Call it blues. Nobody will notice.' And I was right. These are indeed semantic questions, and I try not to let them bother me. People aren't handicapped because they call it all blues, they call it all blues because they are handicapped. They don't pay attention. So, they want to call me that, fine. And I do love to sing blues." And, it must be said, blues is where Van Ronk made his first splash. Fresh from a jug band record he is still trying to forget, (The dread "Skiffle in Stereo," not his excellent Mercury album) he made two records for Folkways which signaled his arrival as the first white, urban singer to find his own voice in the country blues idiom. On those, as well as later albums, he mixed in white folk material, but he always sounded more like a bluesman than a hillbilly ("Mortimer Snerd's music was never mine," is his terse comment on that subject). Blues is also where he found the basis for his guitar technique, in the playing of Furry Lewis, Josh White and Scrapper Blackwell. His principal influence, though, was the Reverend Gary Davis, who tended to eschew blues in favor of more harmonically complex forms like ragtime and gospel. Van Ronk took these techniques into new and hitherto uncharted waters. The result was a style that influenced few blues pickers, but informed the work of songwriters from Bob Dylan and Jackson Browne to Christine Lavin and Bill Morrissey. "I am an accompanist," Van Ronk says firmly, when asked about his playing. "With the exception of a brief time in the 1950's when I wanted to be Mr. Superchops and seize the black belt from Dick Rosmini--fat chance--I've never been interested in that. I'm a singer. And I'm a singer who's very, very fussy about accompaniments. So, everything that I've learned to do on the guitar has been directed toward giving myself a better backup. "What I am is a careful guitarist. I think about what I'm doing. My idol in this regard is Duke Ellington, who paid attention to voicings, timbre, dynamics, tone color and all that kind of thing. When I play "Maple Leaf Rag," there are probably 150 guitarists who could tear me a new asshole playing pretty much the same arrangement I do. But I didn't do that so I could do that. That was a research project, and what I learned from learning how to do that has been applied hundreds and hundreds of times since--to accompaniments, which is what I do do." When one asks Van Ronk where he got the idea for a certain arrangement, the answer is often surprising. He traces innumerable blues accompaniments to Ellington's horn arrangements or Morton's piano pieces. His definitive setting of Joni Mitchell's "Urge for Going" harks back to Domenico Scarlatti, while his chart on Mitchell's "Both Sides Now" is "a pared-down version of the first two measures of the chorus of [the Rolling Stones'] 'Ruby Tuesday.'" The borrowings are often so subtle that even their sources are astonished. Asked about a favorite guitar part, the spare, rolling riff that underlies his version of "Kansas City," Van Ronk tells a story about a concert at the Left Bank Cafe in Blue Hill, Maine. "Noel Stookey [Paul, of Peter, Paul and Mary] lives up there," he recalls. "So I got up and I did 'Kansas City,' and I said, 'Oddly enough I got the idea for this arrangement from one of your homeboys here, Noel Stookey.' I got off and, sure enough, Noel was in the house, and he said 'I don't remember playing anything like that.' So I picked up the guitar and I played that opening riff and I sang, 'Rain, rain, go away, come again another day.' And Noel got up and walked off. I said 'Where the hell are you going?' and he said 'I'm going to get my lawyer.'" In these parlous times, when originality has become prized far beyond its worth and "folk music" fans will chide a singer of traditional songs for doing "covers," it is unusual to give credit so freely. Van Ronk thinks that is just silly. "In this business we all have our hands in each others pockets," he says. "I'm not unique; I know other people think roughly the same way I do. I might acknowledge things that other people won't acknowledge, but then I tend to remember where I got my ideas from and a lot of other people don't. Because most people don't really listen. Again we're back to that theme. They're not even aware that they're hearing something. "Now, I don't use background music. I spend my time up here 999 hours out of a thousand with nothing playing, because I don't put music on unless I propose to listen to it. I don't believe in it. You should listen to music the same way you read a book or make love. Whatever thy hand findeth itself to do, do it with all thy might. Including listening." The insistence on close listening goes back to Van Ronk's early training in jazz, acquired on Saturday afternoons from his first guitar teacher, Jack Norton. "Jack, or 'The Old Man' we used to call him, used to hold court in his apartment in Briarwood, which is in Queens," Van Ronk remembers fondly. "He had been an associate of Bix [Beiderbeck] and Eddie Lang's and he taught several instruments, including guitar, drums and all the reeds. "Jack showed me some of the fingerings I still use, because he was of the old orchestral jazz school. Played non-amplified rhythm guitar, 'six notes to a chord, four to the bar, no cheating,' like Freddie Green [of the Count Basie Band] used to say. But, more important than that, he taught me how to listen. For example there's a game called 'name that sideman.' The way the game is played is somebody puts on a recording and doesn't tell you who's on it, and you have to sit there and name who's on every instrument. "There are people whom you can't fool, who can tell you, 'No, that's not Ben Webster, that's Coleman Hawkins' or 'That's not Pres, that's Buddy Tate, or Paul Quinichette' and be right every time. And that requires a qualitatively different kind of listening. You can't just groove with the music, you have to bloody well pay attention. The Old Man used to put on recordings and we would play 'name that sideman' and we didn't know it, he never told us, but it was listening training. You had to listen with a focus and an intensity that normal people never use. But we weren't normal people, we were musicians. And the kind of listening that normal people do will not serve for a musician. "Without that training I got from Jack and hanging around with other would-be jazz musicians, all the other things wouldn't really mean much," Van Ronk says, and he means it. In terms of musical knowledge, he has often felt like Gulliver in Lilliput beside the unschooled folkies around him, but he can remember his days in Brobdingnag, playing rhythm guitar at jam sessions that could occasionally include giants like Coleman Hawkins or Johnny Hodges. Asked what they thought of his efforts, he grimaces and says "They were always very polite." It may be hard for some listeners to trace the jazz influence in Van Ronk's reading of, say, Ian Tyson's "Four Strong Winds," but he insists it is always there. "The jazz sensibility is essentially a way of looking at music," he says. "And the general rules that apply to singing jazz apply to a great many other musics. Singing a phrase behind a beat. Singing a phrase rubato. Or varying between rubato, legato, then coming in right on the beat. It's a way of interpreting material, almost any material. I wouldn't recommend that Pavarotti try it; I don't think it would help his material much at all. But with a great deal of material, it does work." If jazz became Van Ronk's musical touchstone, he found a complementary discipline in the study of literature, especially poetry. Just as he interprets Woody Guthrie's phrasing with an ear trained by Coleman Hawkins, he will judge an old blues lyric by standards adapted from reading Shakespeare or Walt Whitman. Of course, a lot of people in the folk world cite jazz and poetry as influences, often with more pretension than accuracy. The difference in Van Ronk's case is that he really is grounded in both disciplines, and in both cases his training pushes him not towards complex showiness but towards greater simplicity. "Poetry is automatically suspect to me," he says. "If you're a good enough poet, you can make bullshit sound so beautiful that people will buy it. I used to see Dylan Thomas over at the old White Horse [a neighborhood bar] back in the early 50's, and he used to recite when he had had enough to drink, which was usually. And my jaw would drop: It was beautiful, it was gorgeous. And a lot of it was bullshit. Not all of it, by any means, but a lot. "I have several books of poetry that I wrote between the ages of fifteen and twenty-five that are full of beautiful bullshit. But I came to the conclusion that you should never say anything in poetry that you can't say in prose. Poetry has the same obligation to make sense as any other statement made by the human mouth. That lets out a lot of stuff that is generally considered to be great poetry, but bullshit is bullshit. This is something I learned from, of all people, Ezra Pound, who insisted that poetry be concise and make sense. If it doesn't make sense no one will read it, and if no one reads it, it might as well not be written." Van Ronk's compositions, or at least those he has recorded and performed, tend to be models of clarity. They range from straightforward blues pieces to the romping hokum of "Sunday Street," the late-night, Irish whiskey ballad sound of "Last Call" and the romantic lyricism of "Another Time and Place." And that is not even mentioning the numerous uncredited additions and alterations he has made to the traditional material in his repertoire. Overall, the quality of his writing is so high that one wonders why he does not do more of it. The answer, simply enough, is that he does not need to. "I never set out to be a song writer," he says. "And I don't feel guilty if I don't write a song. I've probably written enough for several albums, especially if I included my culls. But I don't depend on my song writing and if I think something isn't all that great I can afford to drop it. There are plenty of people out there writing good songs; they need another songwriter like a loch in kop [Yiddish: hole in the head]." Also, his own songs are facing stiff competition from his other material. Selected over a lifetime of hard listening, Van Ronk's repertoire is unmatched in the folk world for its range and richness. Songs like "Cocaine" and "Green Rocky Road" have become so closely associated with him that many fans are unaware that he did not in fact write them. This means that when he writes a new song it has to stand up beside forty years of tasteful acquisitions. And Van Ronk has very little sense of favoritism. "If you are a performer, you're a leader," he says. "You are being paid to get up there and say about music, 'This is what I think.' Sometimes you will be wrong, and you'll have to rethink something. It's like the Spanish saying: 'If one man calls you a horse, ignore it. If two men call you a horse, think it over. If three men call you a horse, get a saddle.' But always you are the judge, because you are the performer and you can't abdicate that responsibility. Everything you do is an exposition, a discursion, whether you think of it that way consciously or not." Which seems like as good a thought as any to end with. Now, it's time for another bottle of wine. From his seat on the couch, Van Ronk directs me over to the stereo and I put on the first record. |

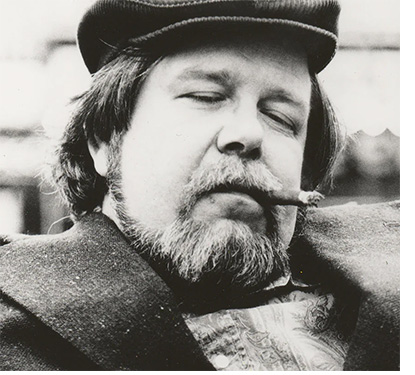

I first saw Dave Van Ronk perform at Boston's Jordan Hall, sometime

around 1972. He remembers the gig as well, because there were about

15 people in the theater. I don't remember anything about that.

All I remember is Van Ronk's incredible stage presence He seemed

to grow and fill the whole room, singing with a hypnotic intensity

that made it impossible to think of anything else.

I first saw Dave Van Ronk perform at Boston's Jordan Hall, sometime

around 1972. He remembers the gig as well, because there were about

15 people in the theater. I don't remember anything about that.

All I remember is Van Ronk's incredible stage presence He seemed

to grow and fill the whole room, singing with a hypnotic intensity

that made it impossible to think of anything else.