Tom Lehrer interview, 1997

by Elijah Wald

[Home] [Wald Bio] [Robert Johnson] [Josh White] [Narcocorrido] [Dave Van Ronk] [Gobal Minstrels] [How the Beatles Destroyed Rock 'n' Roll] [The Dozens] [Dylan Goes Electric]

[Other writing] [Music and albums]

There are a couple of quotations about himself that Tom Lehrer particularly treasures. One, from the Harvard Crimson, says "his enemy is not evil, but benign stupidity.'' The other, from the New York Times, says "Mr. Lehrer's muse is not fettered by such inhibiting factors as taste.''

The 1950s are often remembered as a cultural war zone, with Eisenhower and suburban conformity on one side, and the wildness of rock 'n' roll and beat poetry on the other. Lehrer stood firmly against both, and against decency, compassion, and virtually the whole range of human virtues. His songs, crafted with the care of the great Broadway tunesmiths, were studiedly intellectual and fiendishly irreverent. His idea of a cheerful ditty was "Poisoning Pigeons in the Park.'' His idea of nostalgic sentimentality was an ode to "The Old Dope Peddler.'' His idea of romance was "I Hold Your Hand in Mine,'' a paean to the woman he has killed, but whose hand he has kept as a souvenir.  "I think I could get away with that stuff because I was this clean cut college kid in a bow-tie and horn-rimmed glasses, being kind of innocent and smart,'' Lehrer says. "Obviously educated, using three-syllable words and being almost surprised that the audience thought it was funny.''

"I think I could get away with that stuff because I was this clean cut college kid in a bow-tie and horn-rimmed glasses, being kind of innocent and smart,'' Lehrer says. "Obviously educated, using three-syllable words and being almost surprised that the audience thought it was funny.''

Innocent or offensive, when it comes to straight-ahead humorous songwriting, Lehrer is the standard against which all other writers must be judged, and virtually all are found lacking. His rhymes were so clever, his music such a perfect blend of tin pan alley cliches, and his ideas so fresh and surprising. People might find him heartless or shocking, but they all laughed. "I wanted to write songs that were funny in themselves, as opposed to being sung in a funny voice by a funny person,'' he says. "I didn't think of myself as a comedian, or even a performer; I thought of myself as a demonstrator of songs. I wanted the audiences to go home thinking 'Weren't those songs funny,' rather than, 'Wasn't he funny.' ''

Today, at 69, Lehrer is neither a performer nor a demonstrator of songs. He is a math teacher at the University of California at Santa Cruz one quarter of the year, and a cheerful layabout the rest ("I'm laid back, as we say in California, or lazy, as we say here''). Half the year, he lives in a pleasant house near Harvard Square, moving west for the winter. "I learned 25 years ago that you didn't have to shovel snow,'' he says. "You didn't even have to see snow, and that was a great revelation to me.''

He has not given a public performance since 1972, when he performed some benefits for "losing political candidates and hopeless causes'' (When one of those candidates, Robert Drinan, actually won an election, Lehrer says that it scared him). He has not appeared professionally since 1965, when he briefly emerged after a five-year retirement to play an engagement at San Francisco's Hungry i and record his classic topical album, "That Was the Year that Was.''

And yet, Lehrer is far from forgotten. In the 1980s, his songs were formed into a cabaret revue, "Tomfoolery,'' which was a success in London and New York. The "Dr. Demento'' radio show lists him as one of its two most-requested artists. His three live albums have all been reissued on the Reprise label, and now Rhino records has brought out his two studio albums, together with four rare orchestral pieces and one new recording, on a CD, "Songs & More Songs by Tom Lehrer.''

Lehrer is as surprised as anyone that his work has stayed so popular for so long. That was certainly not what he expected when he started out, almost 50 years ago, performing informally around Harvard house parties. Lehrer entered Harvard as an undergraduate at 15, and wrote his first recorded song, the absurdly effete "Fight Fiercely, Harvard,'' two years later. It was while in graduate school that he began to get a reputation as an entertainer.

"I started out with a group of fellow graduate students and we did songs at the 'freshman smokers' they used to have, where the freshmen would drink beer and throw up on each other. We just sang some parodies that I had written and some original songs. Then they all went their separate ways, and people asked me to do dance intermissions here, which was a common thing in those days.

"There was this place downtown called Alpini's Rendezvous -- it's now a turnpike -- and they said 'Hey,

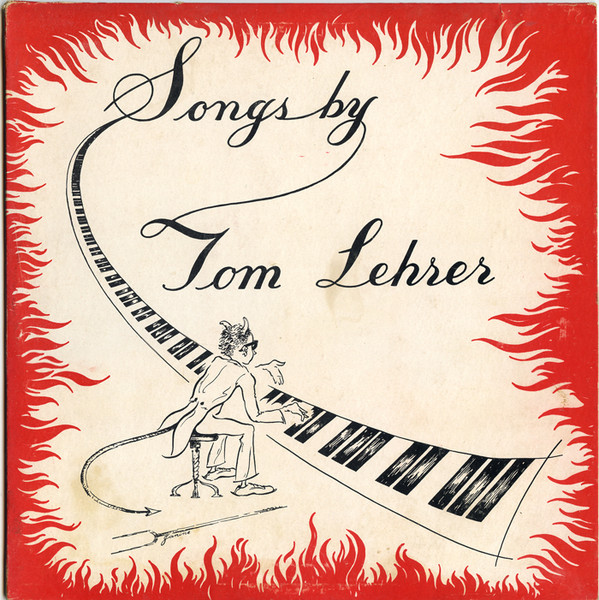

come in Friday, Saturday night for $15.' I would play a little intermission piano and sing a few songs, get the college crowd in. Every week I'd ask them for a raise of $5, until we got up to $30 and he said, 'No, that's too much,' so I quit. And then I put out the record because there was nothing else to do.'' That was in 1953, and Lehrer did it more or less as a lark, pressing 400 copies for sale to his college friends and fans. "I looked in the Yellow Pages for recording studios, and there were two, and one was rude to me and one was polite so I went with the one that was polite. I still have the actual bill for the recording session: it was $15. There was just a microphone and a piano and an engineer. I did each song, played it back, and if it was OK we left it and if it wasn't OK we recorded again over it. So, at the end of the hour we had a 22 minute record, finished and edited.''

That was in 1953, and Lehrer did it more or less as a lark, pressing 400 copies for sale to his college friends and fans. "I looked in the Yellow Pages for recording studios, and there were two, and one was rude to me and one was polite so I went with the one that was polite. I still have the actual bill for the recording session: it was $15. There was just a microphone and a piano and an engineer. I did each song, played it back, and if it was OK we left it and if it wasn't OK we recorded again over it. So, at the end of the hour we had a 22 minute record, finished and edited.''

Fans took the record home on vacations, and orders began drifting in from around the country. "The word spread like herpes,'' as Lehrer puts it, and soon he was making nightclub appearances. After a while he graduated to concert halls, then recorded his second studio album in 1959. That same year, he recorded live versions of both albums, one at Harvard and the other at MIT. (His advertisement for a live set said it "contains exactly the same songs, but unfortunately also includes Mr. Lehrer's tedious spoken commentary.'')

Then, at the height of his popularity, Lehrer quit the entertainment business. "I am not a performer by temperament,'' he says. "I didn't relish doing the same thing night after night. And I don't have the need for anonymous affection. At least, not in the form of people applauding -- I love it when they buy my records.''

He also enjoyed the process of making songs. Along with math, he often teaches a course on the American musical, and he says he would have liked to be a work-to-order songwriter. "I wrote a couple of pieces of 'special material' for other performers,'' he says. "And I wrote the song for a movie called 'A Gathering of Eagles,' with Rock Hudson, about the strategic air command, believe it or not, and an industrial film for Dodge. I was hoping that there would be more of that. I think if I'd played my cards right maybe they would have gotten me for things like 'Toy Story' or 'James and the Giant Peach.' ''

Lehrer toyed with the idea of a musical based on the story of Sweeney Todd, a decade before Stephen Sondheim wrote one, but could not see himself buckling down with a collaborator and turning out a full-length show. Along with his laziness, he ascribes his lack of writing commissions to the fact that people were rarely clear enough about what they wanted, and he could not just turn out "a funny song'' to suit another performer. When the chance came along, he has done some further writing over the years. In the 1970s, he wrote ten songs for public television's "Electric Company'' (two are on the "Tom Lehrer Revisited'' CD), in the 1980s Garrison Keillor got "I'm Spending Hanukkah in Santa Monica,'' and he recently wrote a song on algebra for a CD-ROM. Still, that career never took off and, by now, Lehrer says he rarely writes even for his own amusement. "I'll do it occasionally as a problem-solving exercise, but I don't get the funny ideas anymore,'' he says. "It used to be if the ideas were there I'd write and if they weren't I wouldn't. Then gradually the second condition prevailed over the first.''

"I'll do it occasionally as a problem-solving exercise, but I don't get the funny ideas anymore,'' he says. "It used to be if the ideas were there I'd write and if they weren't I wouldn't. Then gradually the second condition prevailed over the first.''

He also says he has lost much of the firm moral stance that informed his satire, both social and political. The man who once described himself as engaged in an experiment to see how long one could prolong adolescence is "going through a temporary phase of maturity,'' he says. "Maturity means perspective, you can see both sides, and you can't write a funny song with 'on the other hands' or 'howevers' in it. In the old days, I could take a stand and make my position clear. Now, for instance, I'm for the legalization of drugs, but I can also see the counter arguments and so it would be very hard to be funny about it.''

Not that he is complaining. Lehrer's musical career was largely thrust upon him, and he seems utterly unfazed at its disappearance. He is equally unambitious about his academic life, glad that the income from the records has made it unnecessary to pursue institutional accolades. "If I were going to be a real academic, I would have had to go through all the tenure stuff, and publish and go to meetings and all that,'' he says. "This way, I can just do my course and everybody's delighted. I don't have to worry about promotions, and I'm not threatening to anybody.

"I was never interested in expanding the frontiers of human knowledge -- retracting them is more my style. I would never have been good enough to do any original math. I could have gotten by, but I would be an assistant professor of mathematics in Iowa or something like that.''

To someone who knows Lehrer only from his music, this modesty and diffidence is rather surprising. While his record jackets referred to his "so-called voice,'' and his songbook is titled "Too Many Songs by Tom Lehrer,'' there was a sneering sureness to his work that seems utterly unlike the thoughtful, pleasant manner with which he answers over an hour of questions. One expects him to be nastier, more caustic and bitter.

"I don't know what to say to that,'' Lehrer says, bemused. "I'm certainly not personally insulting. I was raised to be polite. Even in the songs, I wasn't making fun, for example, of love. I was making fun of a certain kind of love song. It was hypocrisy that I was aiming at, not the emotion itself. I'm all for love. Love is great. But it sometimes becomes totally unrealistic. I'm not a passionate person by nature, so I have trouble with opera and gospel and things like that. In fact, I'd say that my most profound emotion is chagrin.''

Clearly, Lehrer has not lost the urge to amuse. He likes to come up with clever formulations, and to make the listener smile. As a teacher, he says, "I'm not trying to prove funny theorems or get a laugh with my corollaries, but my theory of pedagogy is to try to teach those who are interested and try not to bore those who aren't.'' He is still something of a performer, and can even be a bit of a ham. Asked, for a photo shoot, to sit at his grand piano, he sweeps into a classical piece, but played in different keys with the two hands, then glances over to see the listener's wince of pain.

Still, he says there is no chance he will ever return to the stage. "People ask me that, and my standard answer is 'Did Hell freeze over?' It would just be an impersonation, like Yul Brynner 25 years later doing "The King and I;" he can barely stand up and people scream and yell because there he is. Also, it would require so much preparation, rehearsing and relearning things. So no, I can't imagine anything that would get me back to doing that. It's like, I liked high school, but I wouldn't want to do it again.''

TOM LEHRER ON SONGWRITING:

Tom Lehrer started out by playing the pop and show tunes of his youth, and that style remains his true love. On record, he dismissed rock as "children's music,'' and the folk revival as "idiocy of the intellectual fringe.'' He speaks admiringly of his influences: Sheldon Harnick, who wrote comic revue material before doing "Fiddler on the Roof,'' and Sylvia Fine, Danny Kaye's wife and lyricist. Among contemporary writers, he lauds Randy Newman, Dave Frishberg, and Stephen Sondheim, "the greatest lyricist the English language has ever produced, and, by the way, a math major in college,'' and has kind words for Paul Simon and Billy Joel.

"There are times when the words are just right, and they're put to music, and that's all I ask,'' he says. "Like I was just listening recently to 'Oklahoma': 'The breeze is so busy it don't miss a tree, and an old weeping willow is laughing at me.' I get all goose-bumpy when I hear something like that, where the words are just exactly right. Not that they're poetry or imaginative or crazy rhymes or something, but they just fit. The music fits and the words fit, and very few people can do that.''

Where other songwriters may stress art, Lehrer admires fine craftsmanship, and he can speak of his own work with the same detachment he applies to others. Speaking of one of his best-remembered songs, "The Elements,'' a setting of the names of all the chemical elements to the tune of the major general's song from "The Pirates of Penzance,'' he says he did it simply as an exercise, imitating a favorite Danny Kaye number, and originally had not planned to perform it.

"I wrote a lot of songs which are no good, but which are like a puzzle,'' he says. "I do the crossword puzzles in Harper's and Atlantic, the hard ones, and it's a nice, satisfying feeling to have done it, or to solve a math problem.

But it's not something I would show it to you and say, 'Oh, look, I solved this problem.' Yes, it's a lot of fun to write a song to use the craft, but the subject matter has to be there, the topic has to be there for it to be worthy of recording.''

Along with the funny material, Lehrer says that he has occasionally tried writing love songs, but always deemed them unworthy. "I have a sheaf of them down there,'' he says, gesturing toward the cellar door. "But they're not of any particular interest, I think, because they are the cliches. That's one thing that I learned very early, and that I've tried to pass on to budding songwriters. I would listen to the radio and think, 'I can write a song as good as that,' and the problem is, they already have people who can write songs 'as good as that' so what do they need one more for? What is necessary is somebody that can write something different.''

©1997 Elijah Wald (originally published in

The Boston Globe)