Elijah Wald – Eric Von Schmidt |

| Back

to the Books

and Other Writing page Back to the Archive Contents page ERIC VON SCHMIDT: ADVENTURES OF A FOLK BUCCANEER By Elijah Wald © 1996 Eric Von Schmidt always wanted to be a pirate, and he seems to have got his wish. The corners of his studio in Westport, Connecticut, are crammed with old swords and firearms, and a bottle of rum sits on the kitchen table, providing a warm antidote to the rain coming down outside. As for the man himself, he could hardly look more raffish and piratical. His rasping laugh reveals a shiny gold tooth, emerging from a grizzled underbrush of beard and mustache. He would not be out of place in some South Seas tavern, regaling wide-eyed youngsters with harrowing tales of mayhem and brigandage.

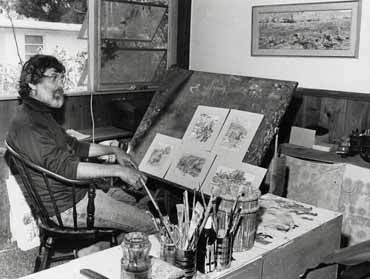

Music and visual art have been the parallel pillars of Von Schmidt's life. He was a published illustrator before he graduated from high school, and he has since produced an unceasing flow of work in multiple media. To the mass public, though, he is best known as a pioneer of the country blues revival, the father of the New England folk scene, and one of the most creative and influential songwriters of the 1960s. Bob Dylan acknowledged his influence on two albums, and his work inspired everyone from Tom Rush and Joan Baez to Johnny Cash. Then, in the 1970s, he co-wrote the authoritative history of the Boston folk boom, Baby, Let Me Follow You Down. Von Schmidt turned 65 this spring, but, at a time when many of his contemporaries are heading toward retirement, he continues to juggle multiple careers. He released a new album last year, is working on an eight-painting series, "Giants of the Blues,'' and is reinvigorating a one-time sideline, writing children's books. Despite almost 50 years as an artist, writer, and musician, the erstwhile buccaneer has by no means settled into a secure and comfortable elder statesmanhood. "It's funny,'' he says, "I was just thinking about this the other day. I realized that, when I see people very concerned about their retirement benefits and health insurance, and all the variety of things that come with having a job -- like a paycheck, for one -- I not only do not have those things now, I have never had them, except for a brief time in the Army, back in the early '50s. There are all those things that people take for granted, like a car that runs. From time to time I had a car that ran, but at the moment I have two cars that don't run.'' Von Schmidt delivers this monologue with a bright smile, and he throws his head back and howls at a suggestion that the Renaissance-man business is not paying like it used to. "All those guys are dead!'' he shouts. "Those people have been dead for centuries! When did you hear of a modern Renaissance man? The closest now is a thing called a polymath, and who would want to be one of those? Oh, it's a rum go these days; it's no fun.'' He pauses for a moment, then laughs again. "Actually, I take that back. It's a lot of fun. But it's certainly not profitable.'' Those last two sentences might serve Von Schmidt as a wry motto, but a better choice would be the phrase he has hammered into a copper sheet and tacked up on his bathroom wall: "We do not compromise with reality.'' Von Schmidt has made his way with singularly few compromises since his childhood, much of which was spent in this studio. His father, Harold Von Schmidt, was a top magazine illustrator whose work appeared regularly in the Saturday Evening Post. As his father's protege, Von Schmidt had his own worktable by the time he was in first grade, and he was more at home in the studio than in the big white house that stands next door. "In the house, I was a child,'' he remembers, "but out here I was accepted as an adult. My father had models hanging around, young guys and girls, and they thought I was cute. We'd play cards and have a good time, and I absorbed a lot of technique in a very benign way, just from watching my father.''

"My father got that in the late '30s,'' he says. "He used it to listen to ball games while he was painting. Well, I was out here one evening working on a poster for a high school dance, and I had that thing turned to WNYC, and all of a sudden this voice comes blasting out of it like nothing I'd ever heard. It was Leadbelly, singing 'Goodnight, Irene,' his theme song. I was going with a girl named Irene at the time, so it was a double whammy, and I said, 'I'm gonna learn that.' And that 15-minute radio show literally changed my life.'' Von Schmidt does not know exactly why he was so captivated. "It would probably take a shrink to sort it all out,'' he says. "And I don't want to deal with those people.'' The pirate thing definitely had something to do with it, though. Von Schmidt had often pretended to be Long John Silver, tying up one leg and stomping around with a croquet mallet as a crutch. Leadbelly, with his mythic past as a murderer who had twice sung his way out of prison, was a modern version of the outlaw archetype, and one that a kid could latch onto just by buying an old guitar. Before the show came on the following week, Von Schmidt had scoured Westport and found two of Leadbelly's 78 rpm record albums. "I took them down to the basement,'' he says, "and it was like the old cartoon by Charles Addams of this little boy in his room, and he's got a chemistry set, and he mixes all this stuff and turns into this incredible monster, and then when his parents are coming, he mixes up more stuff, and when they come in, he's a normal boy. In my case, I went down in the basement for about three weeks, and when I came up, I wasn't a normal little boy anymore. I looked the same, but I sang like Leadbelly.'' Von Schmidt shakes his head at the oddity of a German-American teen-ager from Connecticut singing like an old, black Louisianan, but his passion was genuine. Ramblin' Jack Elliott, the legendary cowboy singer, who met Von Schmidt in 1950, is still impressed by his first taste of Von Schmidt's singing. "He sang Leadbelly's songs with the same kind of spirit Leadbelly had,'' Elliott says. "And he was also the only person I ever heard sing Woody Guthrie's songs really well. Eric's got that wild spirit, and he doesn't water the music down for polite society; he just roars it on out.'' Elliott came across Von Schmidt as a painter rather than a musician, but the painting was of an unusual kind. "Eric was sitting on a scaffolding that was suspended on the stern of a big sailboat, a 75-foot Belgian pilot ketch,'' he says. "He was changing the name to Argosy, and this was a picture on the cover of Argosy magazine. Eric was barefoot, with his legs dangling down, in the middle of painting the name of the vessel on her stern. I went down to the harbor and met him there. He was one of the crew, planning to do a trip around the world with Captain Dod Orsborne, a famous British spy and BS artist.'' It was pirates, once again, and Eric recalls those days with pleasure on an afternoon some weeks after the earlier conversation. The sky is clear, and he is painting outside to take advantage of the sunlight. He mounts the 6-foot canvas on a wooden easel and works it into a corner by the back door, under the branches of a tall maple. A tin toolshed and an old New England graveyard frame a painting of another world: Bessie Smith and her peers, a septet of giant black women, dwarfing an infinite jazz orchestra lined up on the horizon. Von Schmidt talks offhandedly while mixing colors on a glass palette and adding little streaks of pink to Ma Rainey's fan. Reminded of the Argosy, he says that he worked at overhauling it for two years before a draft notice put an end to his seafaring. Elliott's description of Orsborne brings a flood of wry stories, which trail off as Von Schmidt becomes engrossed in his work. He is touching up Ida Cox's dress, painting a bit, then smudging it off with his hand, torn between painting the heavy velvet that Cox would have worn and the current effect, which has her arm outlined through a delicate yellow fabric. The picture is approaching its final form, having evolved dramatically since the last visit. While Von Schmidt may be concerned that some of the dresses still look too wispy, the most obvious change is that, by now, everyone is dressed. A month ago, Smith and two others were naked. "That's how my father used to do it,'' Von Schmidt explains. "His concept was that you understand where the clothes fold much better if you start from a naked person. And it can be helpful. Especially with the quality of a lot of the photographs I had to work from, I figured it would be better if I had an idea of what the hell was going on underneath. It kind of kept me honest and added a little more reality to it.'' Asked if his father used the same method when painting men, Von Schmidt laughs. "No, for some reason, he didn't,'' he says. "And, of course, he used to paint from models. My mother would always ask him that: 'Why don't you paint the men naked?' And he would say, 'I can look in the mirror; I know what a man looks like.' '' The draft curtailed Von Schmidt's nautical venture but did not interrupt his other interests. He spent his two-year hitch in New York as an Army illustrator, practicing his craft and making up his first song, "P Street Blues.'' Then he headed off on a Fulbright fellowship to Italy, where he painted up a storm while trying unsuccessfully to master the bluegrass banjo. Back in the States, he decided to get serious about his painting career, but other forces intervened. He had drastically changed his style in Italy and arrived home with a collection of canvases he describes as "schizophrenic.'' A gallery owner suggested he take a year "to decide which of these guys you are,'' so, with no reason to be anywhere in particular, he came north and got an apartment in Harvard Square. It was to be a momentous move, but that was far from evident at the time. "That was a very poor period in my life,'' he says. "I was pretty much doing anything for anything. I swept out halls, then I got a job working with disturbed kids. That was a fascinating experience, but it was one of those things where, yes, it's fascinating, but you're not painting, and you're champing at the bit and having a hard time paying the rent.'' To keep himself amused, Von Schmidt began hanging out with a bunch of young folks who were interested in older American music, anything from country songs to New Orleans jazz. Mostly they were just jamming, but occasionally someone would get a brief gig. "The first time I ever played at a club that had a microphone and got paid a little bit of money was at Packie's Bar and Grill, which was somewhere in East Cambridge,'' he says. "I was introduced as 'A warm personality: Richard Vaughn.' That was as close as this guy could come to Ric Von Schmidt, or maybe he just figured it would go over better at Packie's.''

At first, the Cambridge scene consisted almost exclusively of informal jamming. Then, one night, a teen-age Joan Baez wandered into Tulla's and "blew the roof off the joint.'' A few days later, Baez got the first folk booking at a jazz coffeehouse down the street, the Club 47, and the folk boom was on. Von Schmidt was one of the first regulars at the 47, playing in a duo with a local guitar virtuoso, Rolf Cahn. Soon they were joined by a crew of new faces: Jackie Washington came over from Roxbury; Tom Rush started his folk show on Harvard radio; Jim Kweskin formed his trend-setting Jug Band out of the loose aggregation of jammers who regularly joined him onstage. "It was a very exciting time,'' Von Schmidt says. "People started thinking, 'Maybe there's other ways to go,' and soon they were dropping out of school and becoming musicians.'' Von Schmidt epitomized the spirit of the burgeoning scene. It was a world where "polished'' and "professional'' were dirty words, and, while his graphic work showed a meticulous technical mastery, Von Schmidt's musical performances were enthusiastically anarchic. His guitar work was often ragged, his songs made up on the spur of the moment, but the energy and passion of his delivery carried everyone before him. Three decades later, Von Schmidt's performances still have the same loose excitement. On stage at Club Passim, which replaced Club 47 in the early 1970s, he moves freely between old chain-gang songs, a recently written ballad about the Alamo, a ragtime shaggy-dog story, and a dark, almost classically complex song about his sea-captain grandfather. The audience is full of old fans and folk luminaries, and they hang on his every word. Younger audience members seem amazed, both at the range and quality of the songwriting and at Von Schmidt's wildly unplanned and unpolished performing style. His enthusiasm is infectious, but also a little disconcerting. It sometimes seems as if he has no more idea than anyone else of what will happen next, and his show, if he can be said to have one, bears no resemblance to the cleanly professional work of the contemporary folk crowd. Von Schmidt understands that his style is unusual, but it is the way he has always done it, and he trusts that the energy and uniqueness of the music will win people over. "I tend to become involved in the emotionalism of the song,'' he says. "To me, it's the spirit more than the expertise that's important. There's a million people who play better guitar than I do, but, to tell you the truth, that never interested me that much. I go back to the old Jimmy Durante saying: 'There's a million good-lookin' guys, but I'm a novelty.' I don't sound like other people; my songs are not like what most people do.'' In earlier times, Von Schmidt's songwriting was unique simply by virtue of its existence. In the 1950s and early 1960s, traditionalism was the order of the day. To write one's own songs was regarded as a questionable mix of hubris and fakery. Von Schmidt recalls that the folklorist John Jacob Niles passed off his original work as "something he got from some milkmaid in the hills of Kentucky. The attitude was, 'There are so many good songs; why bother to write one?' ''

The combination of musical experimentation and outlaw persona made Von Schmidt a role model for a new kid named Bob Dylan, who came to Cambridge on a visit from New York. The pair drove around town trading harmonica licks, then moved on to an afternoon of croquet. "Dylan playing croquet under the influence of half a bottle of red wine and some grass was really hilarious,'' Von Schmidt says. "He couldn't hit the ball with the mallet half the time, and the great thing about it was that he just kind of gloried in it. It was a wonderful meeting, and he ended up at my apartment, and I sang him a bunch of songs, and, with that spongelike mind of his, he remembered almost all of them when he got back to New York.''

Of such small things is history made. Von Schmidt cheerfully agrees that, these days, more people know him from the Dylan references than from his own work. The last few years have been a sort of homecoming for Von Schmidt, both geographically and artistically. While he continued to record into the 1970s, most of his energy for the next decade went into researching and executing three large historical paintings. "Here Fell Custer'' was published in Smithsonian magazine with an accompanying article by Von Schmidt and is now on permanent exhibition in Wichita, Kansas. "Osceola and the Treaty of Renewal'' came next, then the most ambitious project of all, a 10-by-23-foot panorama of "The Storming of the Alamo.'' Both the Custer and the Alamo projects also produced songs, but the only people who heard them were those who dropped by Von Schmidt's homes, which shifted from Florida to Utah and then to a farm in Henniker, New Hampshire. It was not until the late 1980s that Von Schmidt moved back to Westport, where he built a boccie court behind the house and began to hold mammoth parties that drew everyone from veteran folkies to Westport neighbor Keith Richards. As in the old days, informal jamming led to professional engagements. Sam Charters, a friend and producer from the Harvard Square days, offered Von Schmidt a record contract on his Gazell label. Bob Jones, a folksinger and ex-brother-in-law of Von Schmidt's who now books the Newport Folk Festival, arranged for him to appear there for the first time in a quarter-century. As in the 1960s, the music led back into art work. Performers

who remembered Von Schmidt's illustrations for the Joan Baez Songbook and his many album covers and posters began bringing in commissions,

which he executed with his trademark blend of quirky humor and consummate

draftsmanship. His cover for Pete Seeger's latest songbook is an

intricately anachronistic pantheon in which Peter, Paul, and Mary

back Blind Lemon Jefferson, and Shakespeare glances hungrily into

Toshi Seeger's stew pot. His album cover for Rhode Island blues

master Paul Geremia is a Picasso pastiche. Currently, Von Schmidt is engrossed in "Giants of the Blues,'' a projected series of eight large paintings. A canvas of Texas bluesmen is finished, and the first of two groupings of "Blues Women'' is nearing completion. Then there are the children's books, two of which are being polished up simultaneously, and, of course, a variety of musical projects. "My motto has always been, 'If you can't decide which of two things to do, do both,' '' Von Schmidt says, grinning. "In my case, it gets a little out of hand -- sometimes I can't decide between three things and do all three. I should probably stick with the 'both,' but you can put that on my tombstone.'' And, if the careers sometimes collide, or the artistic goals are not matched by the economic rewards, so be it. "I may have sounded like I was complaining earlier,'' Von Schmidt says. "But I always try to add that nobody asked me to do this. For me, the real treat is to get up in the morning and never be quite sure what I'm gonna do next. To me, 'What do I do today?' is a wonderful question. I could revamp an old story or work on a song, or get on with my painting -- whichever one I happen to be working on. It's a very exciting way to go.'' |

The neat, wire-rimmed glasses tell another story, though, and the

implements of destruction are far outnumbered by stacks and rolls

of paintings and prints, filed ceiling-high along two walls. Over

the fireplace hangs a grand historical tableau, "Osceola and the

Treaty of Renewal,'' painted in the style of the 1830s. Two large

canvases with groupings of blues singers stand at right angles on

the floor, marking off a corner desk area and getting in Von Schmidt's

way when he needs to answer the phone. Across the room, by the kitchen

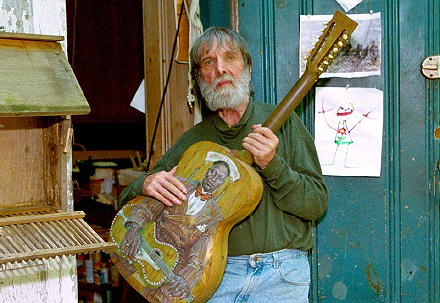

door and the stairs to the bedroom loft, are two guitars, one painted

with a whimsical likeness of Huddie Ledbetter, the legendary bluesman

known as Leadbelly, wearing a butterfly bow tie.

The neat, wire-rimmed glasses tell another story, though, and the

implements of destruction are far outnumbered by stacks and rolls

of paintings and prints, filed ceiling-high along two walls. Over

the fireplace hangs a grand historical tableau, "Osceola and the

Treaty of Renewal,'' painted in the style of the 1830s. Two large

canvases with groupings of blues singers stand at right angles on

the floor, marking off a corner desk area and getting in Von Schmidt's

way when he needs to answer the phone. Across the room, by the kitchen

door and the stairs to the bedroom loft, are two guitars, one painted

with a whimsical likeness of Huddie Ledbetter, the legendary bluesman

known as Leadbelly, wearing a butterfly bow tie. The studio is like a Von Schmidt archive and museum. There are

paintings, bronzes, photographs (including a handsome Dorothea Lange

portrait of the elder Von Schmidt), bound volumes of illustrations,

and the general detritus of two lifetimes. In this haphazard profusion,

it is easy to miss a big, brown short-wave radio that sits by the

window under a couple of dictionaries and a statue of a Balinese

dancing girl, but Von Schmidt points it out with something approaching

reverence.

The studio is like a Von Schmidt archive and museum. There are

paintings, bronzes, photographs (including a handsome Dorothea Lange

portrait of the elder Von Schmidt), bound volumes of illustrations,

and the general detritus of two lifetimes. In this haphazard profusion,

it is easy to miss a big, brown short-wave radio that sits by the

window under a couple of dictionaries and a statue of a Balinese

dancing girl, but Von Schmidt points it out with something approaching

reverence..jpg) Von Schmidt found a more congenial welcome at Tulla's Coffee Grinder,

a cafe on Mount Auburn Street that was the meeting place for some

Harvard students who had discovered old-time country music. In a

few years, the group would gel into the Charles River Valley Boys,

but in 1958, everyone was just fooling around and having a good

time. When Von Schmidt appeared on the scene, he provided a bridge

between the country and jazz crowds and served as a rakish role

model. "This was the tail end of that whole Beat-era thing,'' he

explains. "And I think I represented something of an outlaw to

the Harvard kids. I didn't have to go to school. I was a painter.

I was a few years older than them, and I had a big, black beard,

and I played the guitar, and I was free. Or, anyway, I hadn't been

arrested yet.''

Von Schmidt found a more congenial welcome at Tulla's Coffee Grinder,

a cafe on Mount Auburn Street that was the meeting place for some

Harvard students who had discovered old-time country music. In a

few years, the group would gel into the Charles River Valley Boys,

but in 1958, everyone was just fooling around and having a good

time. When Von Schmidt appeared on the scene, he provided a bridge

between the country and jazz crowds and served as a rakish role

model. "This was the tail end of that whole Beat-era thing,'' he

explains. "And I think I represented something of an outlaw to

the Harvard kids. I didn't have to go to school. I was a painter.

I was a few years older than them, and I had a big, black beard,

and I played the guitar, and I was free. Or, anyway, I hadn't been

arrested yet.'' Von Schmidt knew hundreds of old songs, but he also had met older

singers like Woody Guthrie and had been impressed by the freedom

with which they put their own stamp on the tradition. He saw no

reason to limit himself, and if he had an idea for a song, he would

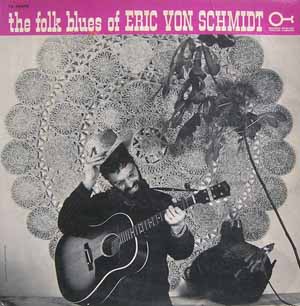

try it out. His first solo album, The Folk Blues of Eric Von Schmidt,

included a calypso interpretation of Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita along

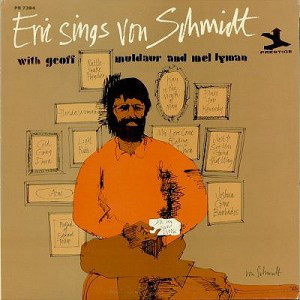

with the classic blues and ballads. His second, Eric Sings Von Schmidt,

was all self-composed, ranging from a teen-age rock lament about

acne to some of the best blues lyrics of the era, as well as his

masterpiece, "Joshua Gone Barbados,'' a Caribbean ballad that has

been recorded by everyone from Dave Van Ronk to Johnny Cash.

Von Schmidt knew hundreds of old songs, but he also had met older

singers like Woody Guthrie and had been impressed by the freedom

with which they put their own stamp on the tradition. He saw no

reason to limit himself, and if he had an idea for a song, he would

try it out. His first solo album, The Folk Blues of Eric Von Schmidt,

included a calypso interpretation of Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita along

with the classic blues and ballads. His second, Eric Sings Von Schmidt,

was all self-composed, ranging from a teen-age rock lament about

acne to some of the best blues lyrics of the era, as well as his

masterpiece, "Joshua Gone Barbados,'' a Caribbean ballad that has

been recorded by everyone from Dave Van Ronk to Johnny Cash. A few months later, the first Dylan album came out. Over the guitar

introduction to "Baby Let Me Follow You Down,'' which Von Schmidt

had adapted from a Blind Boy Fuller tune, Dylan told of meeting

Von Schmidt "in the green pastures of Harvard University.'' It

was not the last tribute: On the cover of Bringing It All

Back Home, Dylan is shown sitting beside a copy of Von Schmidt's

first album.

A few months later, the first Dylan album came out. Over the guitar

introduction to "Baby Let Me Follow You Down,'' which Von Schmidt

had adapted from a Blind Boy Fuller tune, Dylan told of meeting

Von Schmidt "in the green pastures of Harvard University.'' It

was not the last tribute: On the cover of Bringing It All

Back Home, Dylan is shown sitting beside a copy of Von Schmidt's

first album.