As I write, Israeli troops are massed on the no man’s land separating Israel from Gaza, shooting tear gas grenades and live ammunition at Palestinian refugees who are gathered on the other side, throwing rocks, burning tires, and seeking to breech the barriers and send thousands of men, women and children across.

As I write, Israeli troops are massed on the no man’s land separating Israel from Gaza, shooting tear gas grenades and live ammunition at Palestinian refugees who are gathered on the other side, throwing rocks, burning tires, and seeking to breech the barriers and send thousands of men, women and children across.

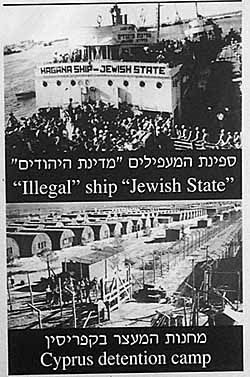

The pictures and news reports are eerily reminiscent of films, photographs, and personal testimonies displayed and celebrated in Israeli museums and on historical markers like the one on the hill above Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum in Jerusalem, which honors the 85,000 “illegal immigrants” who “attempted to enter the country, breaking through the maritime and land blockade,” making “a vital contribution to the growth of the Jewish Yishuv, and to its struggle for an independent state.”

In Tel Aviv, the museum of the Hagganah, the Jewish army that faced British and Arab forces in the late 1940s, has a display honoring “Ha’apala – Clandestine (Illegal) Immigration, 1934-1944,” and two museums of the Etzel, the more radical Jewish underground, likewise celebrate the brave men and women who smuggled Jewish refugees into Palestine, defying the British army and even the Haggana, which in some periods helped the British, much as the Palestinian Authority’s police now work with Israeli forces to control illegal migration from the West Bank.

In Tel Aviv, the museum of the Hagganah, the Jewish army that faced British and Arab forces in the late 1940s, has a display honoring “Ha’apala – Clandestine (Illegal) Immigration, 1934-1944,” and two museums of the Etzel, the more radical Jewish underground, likewise celebrate the brave men and women who smuggled Jewish refugees into Palestine, defying the British army and even the Haggana, which in some periods helped the British, much as the Palestinian Authority’s police now work with Israeli forces to control illegal migration from the West Bank.

The most striking celebrations of illegal Jewish immigration are further north: the Atlit Detention Camp south of Haifa has been turned into an outdoor museum where tourists can learn about the Ha’apala or Aliya Bet – Aliya being the Hebrew word for Jewish immigration to Palestine, and Bet the first letter of bilti-legalit, “illegal” – and Haifa has a Museum of Clandestine Immigration run by the Israeli Ministry of Defense.

The guidebook sold in the museum shop describes the various ways Jewish immigrants made their way into Palestine in the 1920s and ’30s — some paying sailors to land them surreptitiously, some sneaking over the Lebanese border, some arranging fictitious marriages, some overstaying tourist visas. The central exhibit space is a ship that was used to bring more than 400 Jewish refugees from Europe in 1947. A documentary film, screened in the bowels of the ship, tells how it almost made it to Palestine without being detected, but eventually was spotted by a British plane, then overtaken by a destroyer.

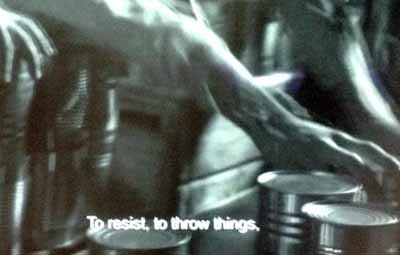

Itzak Belfer, one of the passengers, describes how the British troops were massed on the deck of the destroyer, and someone brought up boxes of tin cans to throw at the soldiers. One of the men commanding the ship for the Palyam, the Jewish rebel navy, recalls: “We told them to give the British a hard time — to resist, to throw things, not let them board the ship, and maybe we could make it to the shore.”

Itzak Belfer, one of the passengers, describes how the British troops were massed on the deck of the destroyer, and someone brought up boxes of tin cans to throw at the soldiers. One of the men commanding the ship for the Palyam, the Jewish rebel navy, recalls: “We told them to give the British a hard time — to resist, to throw things, not let them board the ship, and maybe we could make it to the shore.”

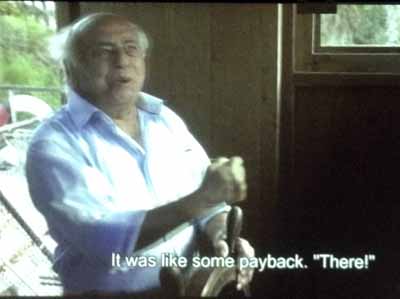

The British soldiers began to board, and Belfer, his voice thrilling at the memory, recalls throwing the cans of food at them: “That kind of can, when someone throws it, it can do a lot of damage.” Then the Palyam man on the ship’s bridge angrily turned the wheel and rammed their boat into the destroyer. “We were all knocked down,” Belfer says, but “We all felt like… ‘We did it! We showed them!’”

The British soldiers began to board, and Belfer, his voice thrilling at the memory, recalls throwing the cans of food at them: “That kind of can, when someone throws it, it can do a lot of damage.” Then the Palyam man on the ship’s bridge angrily turned the wheel and rammed their boat into the destroyer. “We were all knocked down,” Belfer says, but “We all felt like… ‘We did it! We showed them!’”

At the Atlit refugee camp, in a similar ship, a more theatrical film shows actors recreating a nighttime shipboard battle, throwing cans and fighting hand-to-hand as a brave young woman climbs the mast to wave the flag of the potential Israeli state:

Leaving the ship, I had a brief conversation with the young Israeli woman who was serving as a guide in lieu of her regular military service. I was curious if she made the same connection I did, and prompted her with a leading comment:

“I have to say those films of the Jews throwing things at soldiers remind me of what I’m seeing in the newspapers now.”

“Yes,” she replied, smiling. “It’s amusing that history does repeat itself.”

“Amusing?”

“I find the irony amusing, that we keep doing the same.”

“I’d like to think we could do better.”

“Yes, me too. But apparently we can’t.”