“Every time you see a cop on the beat, ask yourself what he is protecting, and from who.”

“Every time you see a cop on the beat, ask yourself what he is protecting, and from who.”

— Malcolm X1

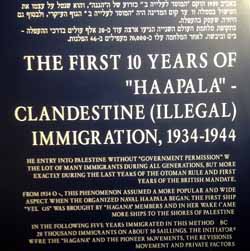

Traveling in Israel, I was pleasantly surprised to find that Haifa’s tourist sites include a museum celebrating illegal immigration. It’s actually called the Clandestine Immigration and Naval Museum, but they aren’t fussy about the nomenclature: the book they sell in the gift shop, published by the Israeli Ministry of Defense, constantly uses the term “illegal immigration” and refers to the people who arrived that way as “illegals.” It describes how some paid sailors to land them surreptitiously, some snuck over the Lebanese border, some arranged fictitious marriages, some overstayed tourist visas… in sum, all the current methods by which people continue to make their way to new countries in defiance of various authorities.

In light of recent headlines I was particularly struck by the museum’s film of illegal immigrants throwing metal cans at British soldiers who were trying to keep them from landing in Palestine (from which I shot a photo sequence):

I’ve written about the similar exhibit and film at the Atlit Detention Center museum, and welcome the reminder that not long ago my relatives were not only sneaking across borders, but facing uniformed soldiers with nothing but what they could throw, and exulting in making at least that show of resistance. That reminder is particularly relevant today, when descendants of those brave “illegals” have elected a government that is increasingly notorious for building walls, policing borders, and violently repelling anguished refugees who want to come home to Palestine.

This sort of turnabout is often described as ironic… but the sad fact is it’s normal. When people get a taste of power or put on uniforms, they tend to behave like people with power and uniforms. When people have a nation-state, they tend to assume the right — and often the necessity — to guard its borders. And, by contrast, when people don’t and are desperate they throw whatever they can throw and damn the consequences.

So I’m not calling it ironic, but it is an obvious reminder that what seems heroic when you’re on one side can seem very different when you’re on the other, and vice-versa.  And I’m glad all the museums and historical sites use the word “illegal,” because although I understand why some people prefer euphemisms like “undocumented” and “unauthorized,” the reality is that governments make laws to protect some people from other people — and when you argue that the people you support are not criminals, you are arguing that other people can justifiably be labeled that way.

And I’m glad all the museums and historical sites use the word “illegal,” because although I understand why some people prefer euphemisms like “undocumented” and “unauthorized,” the reality is that governments make laws to protect some people from other people — and when you argue that the people you support are not criminals, you are arguing that other people can justifiably be labeled that way.

History and fiction are full of stories of brave outlaws and we all can think of actions, past and present, that have been both heroic and illegal – as well as arguably pointless, like throwing tin cans at a destroyer full of British soldiers or boxes of tea into Boston Harbor. When it comes to border-crossers, the judgment of history and myth is identical and clear: there are no heroic narratives of repelling migrants – when anti-immigrant pundits compare their country to a crowded lifeboat, the metaphor emphasizes at least a feigned regret and no one pretends there is anything heroic about beating back drowning swimmers.

Myths of heroic outlawry often founder on close examination — the rebels and outlaws celebrated in song and story turn out to have killed, raped, abused, and behaved horrifically not only to oppressors but to innocent unfortunates who happened to cross their paths. But the same can be said of every army and most governments — no rebel band has ever racked up a toll of victims that matches the worst horrors of official troops and police –- and the fact that myths are idealizations does not make them meaningless.

The Israeli contrast –narratives of desperate Jewish refugees throwing cans at soldiers seventy years ago, told to rally support for Jewish soldiers shooting desperate refugees throwing stones today – is particularly striking because the time and space are so compressed. But the essential contrast is so familiar as to be almost universal: virtually all national narratives include brave struggles against oppressive governments, and few governments maintain their power for long with clean hands.

The Israeli contrast –narratives of desperate Jewish refugees throwing cans at soldiers seventy years ago, told to rally support for Jewish soldiers shooting desperate refugees throwing stones today – is particularly striking because the time and space are so compressed. But the essential contrast is so familiar as to be almost universal: virtually all national narratives include brave struggles against oppressive governments, and few governments maintain their power for long with clean hands.

There are many possible morals here, and I’m not pretending the answers are easy or uncomplicated. But one cannot simultaneously stand up for the oppressed and defend the rule of law, because the oppressors are almost always lawmakers and all of us can come up with examples of unjust laws and people who have heroically resisted them.

There are also whole classes of laws that are inherently unjust, including the many laws that trap people in desperate situations because of accidents of birth or nationality. Regarding the Israel-Palestine situation, I have spoken with Israelis who think I am hopelessly naive, or accuse me of switching sides, or argue it is so complicated that the the sides are hard to define. I likewise know Americans and Europeans who feel they can’t choose sides, and don’t see a direct parallel to their own countries. But I keep coming back to those overlapping images from past and present, and thinking the people guarding borders against desperate immigrants are always on the same side, whoever and wherever they may be.